A conceptual framework for determinants of health (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2014)

Behavioural determinants include a range of behaviours that may directly cause disease, such as tobacco smoking or alcohol consumption, while other determinants, such as socio-economic status, act further up in the causal chain (and may be thought of as ‘causes of the causes’). It has been suggested that individuals have a certain level of control over some of the determinants (such as sedentary behaviour), while other determinants that influence health are outside of an individual’s control (such as environmental determinants like poor sanitation and climate change) (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2014).

- Behavioural determinant

a personal attribute or behaviour that influences an individual’s risk of experiencing poor health.

In reality, most determinants are the result of a combination of factors. Take for example nutritional determinants of health. Good nutrition is often considered the result of individual choices and preferences. However, an individual’s food choices are heavily influenced by social and cultural norms, which are in turn influenced by food marketing and promotion, availability, affordability and access (Coulston, Boushey & Ferruzzi, 2013; Monteiro, 2009).

- Nutritional determinants of health

diet-related factors that affect human health, such as nutrition, food availability and access.

It is vital to understand that the determinants of an individual’s health are fundamentally interrelated, often described as a ‘web of causes’ (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2014) and perhaps better termed as ‘patterns of determinants’ (Kindig & Stoddart, 2003) which cannot be addressed in isolation. Effective public health interventions therefore need to identify and understand individual behaviours but look beyond them to wider determinants.

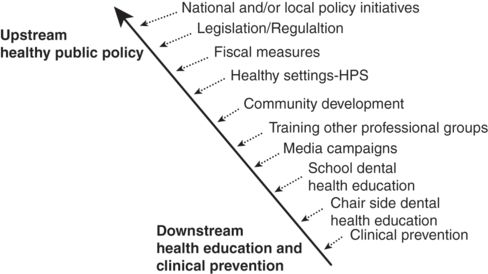

Interventions can be framed in terms of whether they are ‘upstream’ or ‘downstream’. Upstream interventions address big picture determinants at the level of society and policy, whereas downstream interventions target individual determinants such as biological risk factors, lifestyle and education (Watt, 2007; Lorenc, Petticrew, Welch & Tugwell, 2012). Figure 6.2 below provides examples of interventions along this spectrum. Upstream interventions align with the social determinants of health approach and have greater potential for reducing social inequalities (Watt, 2007; Lorenc et al., 2012).

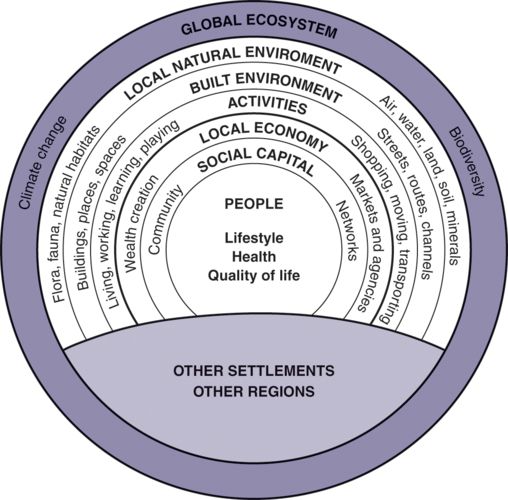

As explored in the previous chapter, health is heavily influenced by our social structures that create inequalities and influence our available choices (Denton, Prus & Walters, 2004). A socio-ecological view of health (Whitehead & Dahlgren, 1991) focuses on both individual- and population-level health determinants which can only be effectively addressed by looking to domains external to the health sector such as housing, agriculture and education (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, n.d.).

This ‘ecosystem’ situates the individual and their personal characteristics within their living and working conditions, the social and economic resources and opportunities available, and the built and natural environment (Figure 6.3) (Barton, 2005). From a public health perspective, it is important to keep in mind that not all of these determinants are equal in their impact on health. In addition, some determinants may be affected by personal choices while others may require policy or structural interventions, which can take significantly more time to achieve and often require high levels of political will (Shi & Zhong, 2014).

Identifying the factors that influence health is important to prevent disease and promote health. It is also necessary to differentiate the factors about which little can be done (for example, age and genetic inheritance) from those which may be modified (for example, built environments, social norms and individual behaviours). This chapter explores behavioural, nutritional and environmental determinants and describes the different levels of influence these have on health outcomes to illustrate key considerations when developing effective public health responses.

Behavioural determinants of health

Behavioural determinants of health are those personal attributes (for example, values and beliefs), personality characteristics (including emotional states) and behavioural patterns that may increase or decrease the risk of poor or good health outcomes (Glanz & Stryker, 2008). These include risk or protective behaviours such as alcohol and other drug use (licit and illicit), dietary behaviour, breastfeeding or sexual practices; as well as individual responses to health problems such as help seeking, compliance with medical treatment or healthcare service use (NSW Department of Health, 2010). Traits, actions or exposures that increase the likelihood that an individual will develop a disease or injury are known as risk factors. Protective factors are those that reduce this likelihood (World Health Organization, n.d.).

Behaviour change

Motivation to engage in certain behaviours is not static, so behaviour change should be viewed as a complex process, not an event (Glanz & Stryker, 2008). The ‘risk’ of developing disease or incurring injury may motivate some individuals to change their behaviour. For example, some individuals may respond to road safety messages about the risk of serious injury or death when not wearing a seatbelt while driving. However, many people continue to practise health-damaging behaviours even when they know that they can be harmful. Individuals vary in their perceptions, understanding and assessment of risk depending on their personal experience and social context (Prestage, Brown, Down, Jin & Hurley, 2013).

Determining the factors that underpin an individual’s decision to undertake a behaviour, or not, is important. For example, over the past decade Western Australia has experienced an increase in overseas-acquired HIV among migrants and travellers (Brown et al., 2014). Australian men who have reported acquiring HIV overseas, primarily in South East Asia, differ in their experiences and perceptions of risk. For some, infection has occurred because the cultural context provided extensive opportunities for sexual interactions that were previously unavailable. For others, greater risk occurred if a practice of inconsistent condom use in Australia was continued in a country with higher HIV prevalence (Brown et al., 2014).

Behaviour change theories can improve our understanding of such complexities by explaining behaviour and suggesting ways to create or enhance behaviour change (Glanz & Rime, 1995). No single theory or model by itself can hope to explain human behaviour. The fact that a person may have knowledge about the risks and consequences of their behaviour does not ensure that they will change that behaviour. They also need to have a positive attitude towards adopting a new behaviour and the skills to carry it out. An environment that is health enhancing and supportive makes this change more likely. Even when all of these elements are present the individual may still choose not to take up the healthier option (Egger, Spark & Donovan, 2013). Understanding the process of behaviour change and the context it operates in is critical for public health to better determine how to make the healthier choice easier.

Health behaviour: a ‘lifestyle choice’?

The use of ‘lifestyle choice’ to describe these behaviours has often led to ‘victim blaming’, distracting from the root causes of poor health (Kelly et al., 2008). ‘Victim blaming’ occurs when individuals are blamed for their poor health, instead of recognising the significant environmental, social and systemic factors that affect health outcomes (Hoek & Jones, 2011). Health promoting and compromising behaviours (Watt & Sheihan, 2012) are formed over time, deeply embedded in an individual’s cultural and environmental context (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2007; Prochaska & Diclemente, 1986) and history. They are not ‘solely the result of current conditions and individual lifestyle choices’ (Sundmacher, Scheller-Kreinsen & Busse, 2010, p. 2).

Many university students drink heavily. Around half in Australia report binge drinking and experience greater alcohol-related problems than their non-student peers. These include individual harms (such as academic impairment, personal injury and unintended sexual activity), harms to others (for example, interpersonal and sexual violence) and harms to their institution (for example, property damage, student attrition) (Hallett et al., 2012). Men are more likely to experience ‘public domain’ consequences (for example, aggression and property destruction) and women are more likely to experience personal harms, which frequently go unreported (Hallett, McManus, Maycock, Smith & Howat, 2014).

University environments contribute to high levels of alcohol consumption. High concentrations of young people (many of whom have only recently been able to purchase alcohol legally), a shift of influence from parents to peers, the accessibility of cheap alcohol on campus, social events focused on drinking, and study-related stress all contribute (Hallett et al., 2014).

University students are typically reluctant to seek help for their drinking although some have indicated a preference for web-based programs over face-to-face clinical services (Kypri, Saunders & Gallagher, 2003). One such intervention is THRIVE, developed at Curtin University, which uses technology to apply an individual-level intervention to a whole population. THRIVE is a web-based assessment of alcohol consumption providing personalised feedback. It comprises a hazardous-drinking score, feedback about individual risk, comparison to peers, alcohol facts and tips, and referral for medical and counselling support (Hallett, Maycock, Kypri, Howat & McManus, 2009).

At Curtin University, THRIVE reduced alcohol consumption among heavy drinkers and prompted students with unhealthy alcohol use to seek additional help (Kypri et al., 2009). THRIVE has been further implemented with Queensland (UQ Health Service, 2010) and New Zealand university students (Kypri et al., 2013), hospital outpatients (Johnson et al., 2013) and US veterans (Lapham et al., 2012). The Parliament of Western Australia has called for the expansion of such programs to all tertiary institutions in Western Australia (Education and Health Standing Committee, 2011).

For more information, see http://ceriph.curtin.edu.au/thrive.

Nutritional determinants of health

Food is a basic human need and access to adequate food (regular supply of safe, nutritious and affordable food) is a fundamental human right. People who regularly eat a nutritious diet are more likely to be healthy and have a reduced risk of diet-related chronic disease. Defining a nutritious diet is challenging because nutrition needs change over the life course (Black et al., 2013; Coulston, Boushey & Ferrussi, 2013) and also depend on physical activity levels, health status and gender.

Dietary recommendations for populations

The strength of evidence for dietary advice for health and wellbeing is strong and increasing (Allman-Farinell, Byron, Collins, Gifford & Williams, 2014). This has led the World Health Organization to call for countries to develop food-based, culturally specific dietary guidelines and food selection guides based on the latest scientific evidence and the available food supply (World Health Organization, 2004, 2013). Dietary guidelines provide credible and reliable dietary advice at a population, local and individual level and provide the basis for nutrition education, programs and policies. They aim to prevent and manage diet-related chronic diseases including obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and some cancers. For more information on Australia’s dietary guidelines produced by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) in 2013 see https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au.

Generally, dietary patterns to promote health include eating plenty of vegetables (including legumes), fruit and whole-grain cereal foods, moderate amounts of lean meats and/or meat alternatives, and reduced-fat dairy foods while at the same time limiting foods and drinks that are energy dense and nutrient poor (for example, alcohol, sugar sweetened beverages, and foods containing added salt and/or sugar and saturated fat) (Hamer & Chida, 2007; Buckland, Bach & Serra-Majem, 2008; Takachi & Tsugane, 2008; World Cancer Research Fund International, 2007).

Within a country, dietary behaviours tend to be relatively homogenous due to the cultural norms and the available food supply. However, as countries become wealthier, a nutrition transition can occur, resulting in a double burden of malnutrition: ongoing growth stunting and essential nutrient deficiencies alongside micronutrient deficiencies in obesity and increasing diet-related chronic diseases (Black et al., 2013).

Food environments

Food environments shape dietary intake and burden of disease. Modifying the external environment in which people live supports individual dietary change (Monteiro, 2009). An ecological approach is recommended to address the social, cultural and economic factors contributing to the formation and maintenance of dietary habits (Lang & Rayner, 2007). To ensure a comprehensive approach, it is recommended that frameworks for action are considered. For example, the NOURISHING framework (Hawkes, Jewell & Allen, 2013) outlines policy options and actions to improve nutrition by focussing on:

food environments:

Nutrition labels

Offering healthy foods

Using economic tools

Restricting food advertising

Improving the quality of the food supply and

Setting incentives and rules for a healthy retail environment

food systems:

Harnessing supply chain actions to ensure health coherence and

behaviour change:

Inform people

Nutrition advice

Giving public education and skills.

- Food environment

the physical and social settings where the cost and availability of food and its cultural associations influence what people eat.

Nutrition priorities

Food policy for public health has the vision of ‘a safe, nutritious, affordable, secure and environmentally sustainable food system accessible to all Australians for health, wellbeing and prosperity now and into the future’ (Public Health Association of Australia, 2012, p. 2). To achieve this vision, key nutrition priorities include:

1 improving diet quality while reducing total energy intake to maintain a healthy body weight

2 good maternal nutrition and breastfeeding infants exclusively until around six months and then for about six months as solids are introduced

3 ensuring a safe and sustainable food supply, and

Ongoing action is required to address all of these priority areas at a population level and also to assist those most in need. Governments are encouraged to provide leadership and work with many sectors to create a demand for healthy food environments to reduce the risk of overweight and obesity and related chronic diseases (Swinburn et al., 2015).

Increasing fruit and vegetable intake is considered the single most important dietary change to improve health. The Western Australia Health Department’s ‘Go for 2&5’ fruit and vegetable campaign is a comprehensive social marketing approach to increase consumption. Theory guided the campaign development, and concepts were tested with target audiences; it was found that although improving nutrition was important it was not the highest priority for consumers (Pollard, Daly & Binns, 2009).

The goal was to increase population average fruit and vegetable consumption by one serve over five years by targeting ‘household food shoppers/meal preparers’. ‘Go for 2&5’ aimed to increase awareness of the need to eat more fruit and vegetables, improve perceptions of the ease of preparing and eating vegetables, and encourage increased consumption. ‘Go for 2&5’ provided solutions for quick, easy, convenient, tasty and good value meal preparation by integrating multiple strategies:

high reach mass communication (television, radio, press, website)

point-of-sale promotions

publications/cookbooks

school activities/curriculum resources

sports and arts sponsorships

FOODcents budgeting, shopping and cooking skills development program (Foley, Pollard & McGuiness, 1997), and

uniting agriculture, health, education, retail, producers, and non-government organisations (Pollard, Lewis & Binns, 2008).

The World Cancer Research Fund International featured the campaign as a successful example for global food policy because of its potential for international replication. ‘Go for 2&5’ achieved its objectives (Pollard et al., 2008) with more than 90% of the population aware of the campaign when prompted, significant increases in the proportion who knew the recommended servings and accurate perceptions of their own current intake, and increases in individual consumption, particularly for vegetables (Pollard, Miller, Woodman, Meng & Binns, 2009). For more information, go to http://gofor2and5.com.au

Environmental determinants of health

When we talk about the environment in the context of human health we are generally referring to our surroundings and related external conditions, especially as they affect our lives. Access to clean water and air, safe food and a safe built environment are generally acknowledged as the most fundamental environmental determinants of health. These factors determine our likely exposure to potential hazards in our surroundings, and hence our very survival.

- Environmental determinant

an external factor or condition that affects human health, often beyond an individual’s control.

Environmental health determinants contribute to a high human morbidity and mortality across the globe, particularly in developing countries. A 2006 World Health Organization report estimated that approximately one-quarter of the global burden of disease, more-than one-third of the burden among children and almost one-quarter of all premature mortality were due to modifiable environmental factors (Pruss-Ustun & Corvalan, 2006). The specific fraction of disease attributable to the environment varied widely across different disease conditions due to differences in environmental exposures across the regions.

Disproportionate effects

The impact of environmental hazards on human health is dependent on the vulnerability of the affected population. Environmental factors tend to disproportionately affect the impoverished and isolated. This includes those in developing countries as well as the socially disadvantaged groups in developed countries, such as Indigenous Australian communities in remote areas of Australia. These groups are less likely to have the adaptive capacity or resources to manipulate their environment to withstand hazards or to respond appropriately to minimise ongoing impacts (Bertolatti, Hannelly & Jansz, 2015; World Health Organization, 2015).

- Vulnerability

reduced capacity of an individual or group to withstand, adapt, respond and recover from the impact of natural or human-made hazards.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree