Summary content of the articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Wording derived from summaries given in OHCHR. A simplified version of the UDHR is available at http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/ABCannexesen.pdf

Universality and other key features

Perhaps the most important feature of human rights is their universality: the understanding that human rights are rights belonging to all human beings and are fundamental to every type of society. Each person has the same basic human rights, regardless of gender, age, culture, ethnicity, religion, sexuality and (dis)ability.

Individual human rights do not exist in isolation of each other; they are indivisible, interrelated and interdependent. This does not, however, mean that all rights reinforce one another. Rights can affect each other adversely. For example, the right to freedom of expression may interfere with the right to privacy or with the right to freedom from discrimination. In situations of resource scarcity, many rights, such as to a healthy environment, education, health care and social security, may be in competition with each other.

The distinction between absolute and relative rights is important. Absolute rights are those where restrictions may not be placed on them in any circumstances. These include the rights to be free from torture, slavery or servitude; to a fair trial; and to freedom of thought. The right to life is not absolute; what is forbidden is arbitrary deprivation of life. The right to freedom of thought/opinion and the right to hold any opinion do not include unlimited right to free expression of opinion; this is qualified by restrictions relating to the protection of the rights of others or in certain specific circumstances. This illustrates the complex interdependence that exists between the achievement of rights of different groups within the same community. Some of the articles in the conventions and covenants provide guidance on when rights can justifiably be restricted; this is discussed further in the next section.

Regional human rights systems

Established regional human rights systems, based on a human rights charter, together with some regional enforcement mechanisms, exist in Africa, the Americas and Europe. In Asia and the Middle East, more limited regional developments have taken place. The case study that began this chapter showed how the regional system in the Americas was used to secure an important legal change in Brazil of public health importance.

In Africa, the basic regional human rights instrument is the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights. Human and peoples’ rights are set out in articles 1 to 26 of that charter. The particular formulation used in the charter, as well as within the title of the associated commission and court, of ‘human and peoples’ rights’ rather than simply ‘human rights’ can be seen as a move to include explicitly the notion of ‘collective rights’ held by a group as well as ‘individual rights’ held by every person.

There are two overlapping regional systems in Europe. The first is based on the European Convention on Human Rights, associated with the Council of Europe, which was signed in 1950 and entered into force in 1953; its original title was the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. The European Court of Human Rights covers the Council of Europe member states that have ratified the convention. The second European system is associated with the European Union (EU), and based on the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (EU, 2000). An analysis by McHale (2010) concluded that, although the charter potentially has considerable implications for health law and health policy throughout the EU, its long-term impact is uncertain.

National human rights institutions

In the time since the establishment of the UN, national systems for supporting human rights have developed in terms of different types of national human rights institutions (NHRIs). Pohjolainen (2006) distinguishes four different functions that NHRIs may have: (1) monitoring of observance of human rights, including sometimes the investigation of complaints; (2) advisory, providing advice to the government and sometimes to other relevant actors; (3) education and information, including awareness-raising, education and training; and (4) research, undertaking specific investigations, studies and sometimes public inquiries.

At the national level, possibilities depend on the position of human rights within the country concerned and the nature of the country – leading in some cases to more than one NHRI. The World Conference on Human Rights in 1993 endorsed the establishment of national institutions (UN General Assembly, 1993) and the use of the ‘Principles relating to the status of national institutions’ that had been formulated in 1991 and are generally known as the ‘Paris Principles’ after the city where they were formulated. The main features of the Paris Principles are (1) a mandate with emphasis on the national implementation of international human rights standards; (2) independent of the state; (3) pluralist representation of civil society and vulnerable groups in governance mechanisms; and (4) handling of complaints from individuals (derived from Lindsnaes, Lindholt & Yigen, 2000). At April 2015, there were 106 NHRIs wholly or partially in compliance with the Paris Principles listed on the website of the International Coordinating Committee of National Institutions for the Promotion and Protection Of Human Rights (http://nhri.ohchr.org), and on their global list a total of 145 institutions (http://nhri.ohchr.org/EN/Contact/NHRIs/Pages/Global.aspx).

Spotlight 8.1 The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women and the Convention on the Rights of the Child came into force in 1979 and 1990 respectively. The World Health Organization took the lead in carrying out a wide-ranging investigation to look at the extent to which measures to improve human rights move beyond laws and institutions to actually improve the lives and wellbeing of women and children. In a major report, Bustreo and Hunt (2013) summarised evidence from four diverse countries: Brazil, Italy, Malawi and Nepal. They concluded (p. 12) that applying human rights to women’s and children’s health policies, programs and interventions not only helps governments comply with international and national obligations, but also contributes to improving the health of women and children. Yamin (2013) traced the influence of rights-based approaches in women’s health from the 1990s onwards, providing examples of successful impact around the globe.

Why do you think that the formulation of specific human rights instruments for different population groups has proved helpful?

Why are human rights important to public health practitioners?

Human rights are of great importance in public health practice for a number of reasons. First, there are extensive and close links between specific human rights and the social determinants of health, so that action to support human rights is at the same time supporting reduction of health inequity and action to reduce health inequity often also has positive consequences for human rights; this is considered further in the first subsection below.

Human rights also provide a very powerful basis for public health advocacy, based on the understanding of the right to health, discussed in the second subsection below. Since the 1990s, public health practitioners have been heavily involved in the development and use of rights based approaches to support their work. The earliest work was carried out in the field of HIV/AIDS in order to counter the abuses of human rights suffered by those living with HIV/AIDS, and to respond to the evidence that discrimination was resulting in low uptake of HIV/AIDS prevention and care programs (Mann & Tarantola, 1998). The reports cited in Spotlight 8.1 (Bustreo and Hunt, 2013; Yamin 2013) provide a wealth of examples in terms of the importance of rights-based approaches in women’s and children’s health. For a more detailed review of different types of approaches and their application to other health topics, see Taket (2012).

A final reason why human rights are of importance to public health practitioners is that one of the reasons rights can legitimately be restricted is in order to protect the health of the public (for example, in infectious disease control). Conditions in which rights can be restricted are described further in the third subsection below.

Human rights and the social determinants of health

Human rights are closely linked to the social determinants of health. This can be seen through a number of key documents. The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (‘Ottawa Charter’) (World Health Organization, 1986) lists social justice and equity as two of the prerequisites for health, along with peace, shelter, education, food, income, a stable ecosystem and sustainable resources. The report of the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health foregrounds social justice and broad political and economic determinants in the world’s health agenda (Muntaner, Sridharan, Solar & Benach, 2009). Most recently, the debate on the post-2015 development agenda has emphasised that in order to be truly transformative in tackling inequity, human rights must be recognised as its foundation (Pillay, 2013; Pomi, 2015).

The ‘right to health’

One particularly important right for public health practitioners is the ‘right to health’. This is directly stated in the preamble to the World Health Organization constitution, Article 25 of the UDHR mentions health, and Article 12 of the ICESCR makes it explicit. This explicit recognition of the highest attainable standard of health as a ‘human right’, as opposed to a good or commodity with a charitable construct, provides a very powerful basis for public health advocacy. It is important to note that the ICESCR mentions explicitly both mental health and physical health. Other international human rights instruments also address the right to health, both generally and in relation to specific groups.

To help move towards the right to health, the committee responsible for the ICESCR formulated General Comment 14, and the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and World Health Organization have produced a fact sheet on the right to health (Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights/World Health Organization, 2008). One of the key normative points about the right to health is that it extends to the underlying determinants of health (General Comment 14, paragraphs 4, 10, 11). Also important is the participation of population in all health-related decision-making at community, national, and international levels (General Comment 14, paragraphs 11, 17, 34, 54).

Justifiable restrictions on rights: the Siracusa principles and their public health equivalent

Here we look at ‘valid’ or justifiable limitations on human rights. The UDHR and the two covenants all discuss the issue, setting out the circumstances in which limitation of rights can be justified. They do this in two different ways: first in general articles, and then specifically in relation to particular rights. The form of the limitation varies; of particular interest are limitations on public health grounds, applying to rights such as freedom of movement and association, freedom of expression, and freedom to manifest one’s religion or beliefs. Infectious diseases present one clear public health example where restrictions of human rights may need to be considered.

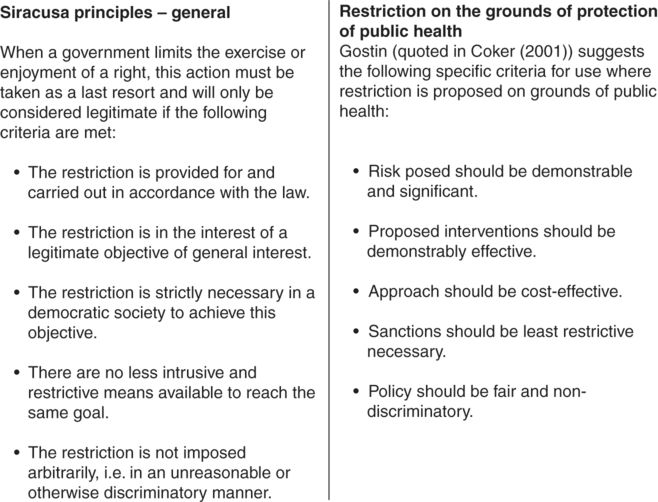

Recognising the difficulty of the judgments that need to be exercised in deciding whether a specific limitation of rights is justified or not, work was carried out to formulate a series of principles to assist such decisions. This resulted in the Siracusa principles, which provide general criteria for rights limitation to be regarded as legitimate. In the case of restriction on the specific ground of protection of public health, Gostin (quoted in Coker, 2001) has formulated some specific criteria; these are both presented in Figure 8.2.

Criteria to assess whether rights can justifiably be limited

The title for this spotlight comes from a video, called I’ll Walk with You, which was released in late 2013 and describes how a network of paralegal professionals is working to ensure people living with HIV have access to law and justice in Uganda. The video explains that, as at 2011, eight people out of every 100 in Uganda are living with HIV, and facing considerable stigmatisation, including through aspects of the law and property rights. Paralegals, many of whom are living with HIV themselves and who are drawn from the communities they work within, help those living with HIV protect their rights. You can watch the video at http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/videos/end-aids-we-must-fight-injustice.

- Justice

fairness

Holding governments to account

The various human rights instruments make clear that the role of governments in respect of human rights can be understood in terms of respecting, protecting and fulfilling rights. So governments must not infringe people’s human rights without justification, and must also go beyond this, protecting rights from infringement by others and taking action to promote fulfilment of rights. Two subsections below consider systems for monitoring and accountability, first at the global level and second at regional and national levels.

Global systems for monitoring and accountability

Corresponding to the nine core human rights treaties, there are nine bodies or committees that monitor countries’ performance. Each country is required to submit an initial report on the extent of its compliance with the treaty in question at the time of the country becoming a party to the treaty. Subsequently, further reports are submitted at four- or five-yearly intervals. Committees also conduct hearings with government representatives to examine progress. NGOs can submit ‘alternative’ reports to the relevant committees; these may be used during the hearings. The Universal Periodic Review is an additional process which involves a review of the human rights record of each UN member state once every four years.

As well as being responsible for monitoring country progress, some of the committees may receive complaints (usually called ‘communications’) that human rights violations have occurred. Communications may be from states – but this is rare (Gruskin & Tarantola, 2005) – or from individuals. Five of the human rights treaty bodies may, under particular circumstances, consider individual complaints from individuals (details can be found on the OHCHR website, http://www.ohchr.org). A committee’s opinions or ‘views’ relating to individual complaints are not binding in any legal sense, but changes in laws or policies may result.

The work of special rapporteurs provides another means of supporting accountability and action. Mandates for special rapporteurs are based on topic and/or situation; they can make country and other visits, send communications to states with regard to alleged human rights violations, and submit annual reports on the activities carried out under the mandate to the commission and the General Assembly. Since 2002 there has been a special rapporteur on the right to health.

Regional and national level possibilities for human rights based accountability and action

The opening case has already provided one example of the successful use of regional systems, namely the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, to achieve progress on public health problems. The website of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (http://www.oas.org/en/iachr) documents fully the activities of this regional system in a series of reports (annual, by country and by topic) as well as extensive details on cases, both completed and in progress.

In Europe, individuals or states can apply to the European Court of Human Rights alleging violation of the European Convention on Human Rights, and judgments made by this court are binding on countries concerned (Goldhaber, 2007). National laws in Europe have been overturned on the grounds that they contravene the European Convention on Human Rights (Neuwahl & Rosas, 1995); for example the court ruled in 1981 that the criminalisation of homosexuality in Northern Ireland was illegal (Dudgeon versus UK; see http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/sites/eng/pages/search.aspx?i=001-57472). The court’s jurisdiction in relation to health is limited, since the European Convention on Human Rights does not contain a specific article on the right to health or the right to health care; however, cases have successfully been brought to support access to health care for marginalised groups. The website of the court (http://www.echr.coe.int) contains country profiles as well as factsheets by topic.

In Africa, the system includes reports submitted every two years to the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights by countries on legislative and other measures taken to support the rights and freedoms set out in the African charter. Country reports are published on the Commission’s website (http://www.achpr.org/), where judgments on complaints (called communications) can also be found.

At the national level, possibilities depend on the position of human rights within the country concerned. In some countries, the right to health or similar rights have been established in national constitutions; others have utilised non-binding policies instead, limiting recourse to courts. As examples of what can be achieved, Singh, Govender and Mills (2007) highlight the health reforms that have been achieved in Argentina, Ecuador, South Africa and India. Hogerzeil, Samson, Casanovas & Rahmani-Ocora (2006) examined completed court cases in low- and middle-income countries where individuals or groups had sought access to essential medicines, with reference to the right to health. The review identified successful cases in 10 countries: eight countries in Central and Latin America, plus India and South Africa. Their interpretation of their findings is that litigation can help ensure governments fulfil their human rights obligations in this respect, but they suggest that the courts should be used as a last resort and that it is better to ensure that human rights considerations are planned into policy and programs.

Brennan, Distler, Hinman and Rogers (2013) compare the effectiveness of four different routes in improving access to essential medicines by reducing the barriers that intellectual property laws create:

(1) the use of human rights arguments in domestic court cases that deal with intellectual property laws, (2) the articulation of norms in the United Nations (UN) human rights system, (3) the use of human rights arguments and frameworks to secure greater pharmaceutical corporate accountability, and (4) the use of health-related rights to build multilateral and regional alliances that can more effectively oppose free trade agreements (FTAs) with TRIPS-plus provisions (TRIPS being Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree