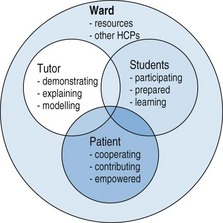

Chapter 11 Clinical teaching at the bedside epitomizes the classical view of medical training. Students are motivated by the stimulus of clinical contacts, but the traditional, consultant-teaching ward round has not been without its shortcomings. Students may feel academically unprepared or inexperienced in the learning style required in an unfamiliar environment (Seabrook 2004). Inappropriate comments, late starts and cancellations may discourage and alienate students so that the value of the experience is dissipated. Finally, today’s teaching hospitals may paradoxically have fewer patients appropriate for bedside teaching despite there being larger student groups attending than before. Despite these problems, ward-based teaching provides an optimal opportunity for the demonstration and observation of physical examination, communication skills and interpersonal skills and for role modelling a holistic approach to patient care. Not surprisingly, bedside teaching and medical clerking have been rated the most valuable methods of teaching. Despite this, bedside teaching has been declining in medical schools since the early 1960s as clinical acumen becomes perceived as being of secondary importance to clinical imaging and hi-tech investigations (Ahmed 2002). Traditional clinical teaching brings together the ‘learning triad’ of patient, student and clinician/tutor in a particular clinical environment. When all works well, this recipe provides a magical mix for producing effective student learning. Direct contact with patients is important for the development of clinical reasoning, communication skills, professional attitudes and empathy (Spencer et al 2000). But for the mix to work, a degree of preparation is required from each party involved. Tutors for ward-based teaching may be consultant staff, junior hospital doctors (Busan et al 2003), nurses or student peers. Kilminster et al (2001) describe teaching by specialized, ward-based tutors as helpful in developing student history-taking and examination skills. Whether they appreciate its significance or not, tutors are powerful role models for students, especially for those in the early years of the course, so it is most important that they demonstrate appropriate knowledge, skills and attitudes (Cruess et al 2008). Prideaux and colleagues (2000) describe good clinical teaching as providing role models for good practice, making good practice visible and explaining it to trainees. Experienced clinical teachers are soon able to assess the patient’s diagnosis and requirements as well as the students’ level of understanding. This ability to link clinical reasoning with instructional reasoning enables them to quickly adapt the clinical teaching session to the needs of the students (Irby 1992). Six domains of knowledge have been described which an effectively functioning clinical tutor will apply (Irby 1994): • Knowledge of medicine: integrating the patient’s clinical problem with background knowledge of basic sciences, clinical sciences and clinical experience • Knowledge of patients: a familiarity with disease and illness from experience of previous patients • Knowledge of the context: an awareness of patients in their social context and at their stage of treatment • Knowledge of learners: an understanding of the students’ present stage in the course and of the curriculum requirements for that stage • Knowledge of the general principles of teaching, including: • Knowledge of case-based teaching scripts: the ability to present the patient as representative of a certain clinical problem; the specifics of the case are used but added to from other knowledge and experiences in order to make further generalized comments about the condition. Tutors responsible for timetabled ward teaching must arrive punctually, introduce themselves to the students and demonstrate an enthusiastic approach to the session. A negative impression at this stage will have an immediate negative effect on the students’ attitude and on the value of the session. Tutors must show a professional approach to the patients and interact appropriately with them and the students (Fig. 11.1). The educational environment of the ward may be affected by many factors which impact on student behaviour and satisfaction (Seabrook 2004). Often district general hospitals appear more valued than teaching hospitals (Parry et al 2002). However, with some thought, some simple problems can be avoided. The use of a side room for pre- or post-ward round discussion provides a useful alternative venue for discussion once the patients have been seen. Occasionally, a member of the nursing staff may be present in the teaching session to add multiprofessional input to the patient care discussion. Stanley (1998) suggests that systematic planning and preparation, especially with increased use of pre- and post-round meetings, would provide more effective and structured training for postgraduate hospital doctors.

Bedside teaching

Introduction

The ‘learning triad’ and its environment

Preparation

Tutors

Appropriate knowledge

getting students involved in the learning process by indicating its relevance

getting students involved in the learning process by indicating its relevance

asking questions, perhaps by using the patient as an example of a problem-solving approach to the condition

asking questions, perhaps by using the patient as an example of a problem-solving approach to the condition

keeping students’ attention by indicating the relevance of the topic to another situation

keeping students’ attention by indicating the relevance of the topic to another situation

relating the case being presented to broader aspects of the curriculum

relating the case being presented to broader aspects of the curriculum

meeting individual needs by responding to specific questions and providing personal tuition

meeting individual needs by responding to specific questions and providing personal tuition

being realistic and selective so that relevant cases are chosen

being realistic and selective so that relevant cases are chosen

providing feedback by critiquing case reports, presentations or examination technique

providing feedback by critiquing case reports, presentations or examination technique

Appropriate attitudes

Hospital ward

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree