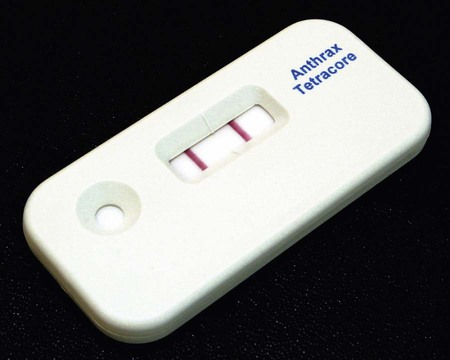

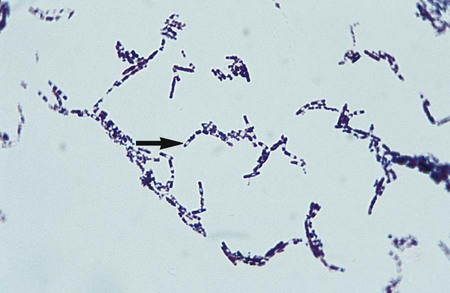

1. Describe the general characteristics of B. anthracis, including colonial morphology and Gram stain appearance. 2. State the location of the organisms in the natural environment, and list the modes of transmission as they relate to human infections. 3. Describe the three forms of B. anthracis infection, including source, route of transmission, signs, and symptoms. 4. Summarize the types of infections associated with B. cereus. 5. Outline the laboratory tests utilized to differentiate B. anthracis from other Bacillus species. 6. State the culture media used to differentiate Bacillus spp., and include the chemical principle and interpretation. 7. Summarize the approach to species differentiation within the genera Bacillus, Brevibacillus, and Paenibacillus. 8. Indicate the appropriate therapy for B. anthracis infection. Clinical microbiologists are sentinels for recognition of a bioterrorist event, especially involving microorganisms such as B. anthracis. Even though this organism is rarely found, sentinel laboratory protocols require ruling out the possibility of anthrax before reporting any blood, CSF, or wound cultures in which a large gram-positive aerobic rod is isolated. During the 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States, the index case associated with the anthrax distribution was discovered by an astute clinical microbiologist who identified large gram-positive rods in a patient’s cerebrospinal fluid. B. anthracis should be suspected if typical nonhemolytic “Medusa head” or ground glass colonies are observed on 5% sheep blood agar. The Red Line Alert Test (Tetracore, Inc., Gaithersburg, Maryland) is a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-cleared immunochromatographic test that presumptively identifies B. anthracis from blood agar (Figure 16-1). The sentinel laboratory anthrax protocol was revised in 2005 and again in 2010 to use FDA-cleared tests in order to rule out nonhemolytic, nonmotile Bacillus spp. as potential isolates of B. anthracis. Anthrax remains the most widely recognized bacillus in clinical microbiology laboratories. It is primarily a disease of wild and domestic animals including sheep, goats, horses, and cattle. The decline in animal and human infections is a result of the development of veterinary and human vaccines as well as improvements in industrial applications for handing and importing animal products. The organism is normally found in the soil and primarily causes disease in herbivores. Humans acquire infections when inoculated with the spores, either by traumatic introduction, ingestion, or inhalation during exposure to contaminated animal products, such as hides (Table 16-1). Bacillus anthracis produces endospores, which are highly resistant to heat and desiccation. The spores remain viable in a dormant state until they are deposited in a suitable environment for growth, including moisture, temperature, oxygenation, and nutrient availability. Because of the ability to survive harsh environments, infectiousness, ease of aerosol dissemination, and high mortality rate, the spores may be effectively used as an agent of biologic warfare (see Chapter 80 for additional information). TABLE 16-1 B. anthracis is the most highly virulent species for humans and is the causative agent of anthrax. The three forms of disease are cutaneous, gastrointestinal (ingestion), and pulmonary (inhalation) or woolsorters’ disease (Table 16-2). The cutaneous form accounts for most human infections and is associated with contact with infected animal products. Infection results from close contact and inoculation of endospores through a break in the skin. Following inoculation and incubation period of approximately 2 to 6 days in most cases, a small papule appears that progresses to a ring of vesicles. The vesicles then develop into an ulceration. The typical presentation is of a black, necrotic lesion known as an eschar. The mortality rate for untreated cutaneous anthrax is low, approximately 1%. TABLE 16-2 Pathogenesis and Spectrum of Disease With few exceptions, special processing considerations are not required. The organisms are capable of survival in fresh clinical specimens and standard transport medium. Refer to Table 5-1 for general information on specimen processing. The Gram stain is the only specific procedure for the direct detection of Bacillus spp. in clinical specimens. Microscopically the organisms appear as large gram-positive rods in singles, pairs, or serpentine changes (Figure 16-3).

Bacillus and Similar Organisms

General Characteristics

Bacillus Anthracis

Epidemiology

Species

Habitat (Reservoir)

Mode of Transmission

Bacillus anthracis

Soil: contracted by various herbivores

Direct contact: animal tissue or products such as wool or hair (infecting organisms)

Trauma or insect bites: organisms or spores

Inhalation: spores; Woolsorters’ disease

Ingestion: contaminated meat

Person-to-person transmission has not been documented

Bacillus cereus, Bacillus circulans, Bacillus licheniformis, Bacillus subtilis, other Bacillus spp., Brevibacillus sp., and Paenibacillus spp.

Vegetative cells and spores ubiquitous in nature; may transiently colonize skin or the gastrointestinal or respiratory tracts

Trauma

Associated with immunocompromised patients

Ingestion of food (rice) contaminated with B. cereus or toxins formed by this organism

Pathogenesis and Spectrum of Disease

Species

Virulence Factors

Spectrum of Diseases and Infections

Bacillus anthracis

Capsule exotoxins (edema toxin and lethal toxin) swelling and tissue death

Causative agent of anthrax, of which there are three forms:

Cutaneous anthrax occurs at site of spore penetration 2 to 5 days after exposure and is manifested by progressive stages from an erythematous papule to ulceration and finally to formation of a black scar (i.e., eschar); may progress to toxemia and death

Pulmonary anthrax, also known as woolsorters’ disease, follows inhalation of spores and progresses from malaise with mild fever and nonproductive cough to respiratory distress, massive chest edema, cyanosis, and death

Gastrointestinal anthrax may follow ingestion of spores and affects either the oropharyngeal or the abdominal area; most patients die from toxemia and overwhelming sepsis

Bacillus cereus

Enterotoxins and pyogenic toxin

Food poisoning of two types: diarrheal type, characterized by abdominal pain and watery diarrhea, and emetic type, which is manifested by profuse vomiting; B. cereus is the most commonly encountered species of Bacillus in opportunistic infections including posttraumatic eye infections, endocarditis, and bacteremia; infections of other sites are rare and usually involve intravenous drug abusers or immunocompromised patients

Bacillus circulans, Bacillus licheniformis, Bacillus subtilis, other Bacillus spp., Brevibacillus sp., and Paenibacillus spp.

Virulence factors unknown

Food poisoning has been associated with some species but is uncommon; these organisms may also be involved in opportunistic infections similar to those described for B. cereus

Laboratory Diagnosis

Specimen Processing

Direct Detection Methods

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Bacillus and Similar Organisms