• Major factors: hypersensitivity of airways; beta-adrenergic blockade; cyclic nucleotide imbalance in airway smooth muscle; release of inflammatory mediators from mast cells. Rate in United States is rising rapidly, especially in children; reasons for this are increased stress on immune system (greater chemical pollution in air, water, and food; insect allergens from mites and cockroaches; earlier weaning of and introduction of solid foods to infants; food additives; higher incidence of obesity; genetic manipulation of plants—food components with greater allergenic tendencies). • Multiple genetic variables increasing susceptibility: deficiency in glutathione S-transferase M1 (gene responding to oxidative stress) increases susceptibility; this suggests need for antioxidants. ADAM33 gene on chromosome 20p13 is linked to airway remodeling (see mediators later) and corticosteroid resistance. Genes on chromosomes 7 and 12 are also implicated. • Mediators: extrinsic and intrinsic factors involving Th2 imbalances trigger cytokine-activated release of mast cell mediators of bronchoconstriction and mucus secretion. Preformed mediators are histamine, chemotactic peptides (eosinophilotactic fac-tor [ECF] and high-molecular weight neutrophil chemotactic factor [NCF]), proteases, glycosidases, and heparin proteoglycan. Membrane-derived agents are lipoxygenase products (leukotrienes [LT] and slow-reacting substance of anaphylaxis [SRS-A]), prostaglandins (PG), thromboxanes (TX), and platelet-activating factor (PAF). Effects of mediators are bronchoconstriction (histamine, LTC4, LTD4, LTE4, PGF2alpha, PGD2, PAF), mucosal edema (histamine, LTC4, LTD4, PAF), vasodilation (PGD2, PGE2), mucous plugging (histamine, hydroxy-eicosatetraenoic acid [HETE], LTC4), inflammatory cell infiltrate (NCF, ECF-A, HETE, LTB4, PAF), and epithelial desquamation (proteases, glycosidases, lysosomal enzymes, and basic proteins from neutrophils and eosinophils). Mediators cause airway remodeling in chronic asthma, affecting epithelium and mesenchymal tissues. Induced growth factors encourage fibroblasts, smooth muscle proliferation, and matrix protein deposits, thickening the wall. • Mild episodic asthma versus moderate to severe sustained asthma: latter has subacute and chronic bronchial inflamma-tion with infiltration of eosinophils, neutrophils, and mononuclear cells. Episodic is caused by bronchial smooth muscle contraction. • Lipoxygenase products: leukotrienes are most potent chemical mediators in asthma. SRS-A (LTC4, LTD4, LTE4) is 1000 times more potent a bronchoconstrictor than histamine. Asthmatics have imbalance in arachidonic acid metabolism, causing relative increase in lipoxygenase products; platelets from asthmatics show 40% decrease in cyclooxygenase metabolites and 70% increase in lipoxygenase products. Imbalance is aggravated in “aspirin-induced asthma”—aspirin and NSAIDs inhibit cyclooxygenase while promoting lipoxygenase, shunting arachidonic acid to lipoxygenase pathway and excessive leukotrienes. Tartrazine (yellow dye #5) is cyclooxygenase inhibitor and induces asthma, especially in children. Tartrazine is antimetabolite of vitamin B6. • Autonomic nervous system (parasympathetic vs. sympathetic innervation): beta2-adrenergic receptors are localized in lung tissue and react to catecholamines. Parasympathetic vagus nerve stimulation releases acetylcholine (Ach), which binds to receptors on smooth muscle, forming cGMP. Increased cGMP and/or relative deficiency in cAMP causes bronchoconstriction and degranulation of mast cells and basophils. Decreased sympathetic activity or diminished beta2-receptor numbers or sensitivity also promotes the cyclic nucleotide imbalance. Some mediators block beta2 receptors and elevate cGMP. • Adrenal gland: cortisol activates beta receptors. Epinephrine (Epi) is the prime stimulator of beta receptors. Asthmatic attacks may be induced by relative deficiency of cortisol and Epi (which stimulate beta2 receptors to catalyze formation of cAMP from AMP), leading to decreased cAMP/cGMP ratio and bronchial constriction. • Pertussis vaccine: among children breastfed from first day of life, fed exclusively breast milk for first 6 months and weaned after 1 year, the relative risk of developing asthma is 1% in children receiving no immunizations, 3% in those receiving vaccinations other than pertussis, and 11% for those receiving pertussis. In a group of 203 not immunized to pertussis, 16 developed whooping cough compared with only 1 of 243 in the immunized group. • Influenza vaccine: although the relatively new cold-adapted trivalent intranasal influenza virus vaccine was deemed safe for children and adolescents, increased relative risk of 4.06 for asthma and reactive airway disease arose in children age 18 to 35 months. • Hypochlorhydria: 80% of tested asthmatic children had inadequate gastric acid secretion; hypochlorhydria and food allergies are predisposing factors for asthma. • Increased intestinal permeability: “leaky gut” permits increased food antigen load, overwhelming immune system, increasing risk of additional allergies and exposure to bronchoconstrictive compounds. — Candida albicans: GI overgrowth implicated as causative factor in allergic conditions, including asthma. Acid protease produced by C. albicans is the responsible allergen. — Food additives: must be eliminated: coloring agents, azo dyes (tartrazine [orange], sunset yellow, amaranth and new coccine [both red]) and non–azo dye pate blue. Most common preservatives are sodium benzoate, 4-hydroxybenzoate esters, and sulfur dioxide. Sulfite sources are salads, vegetables (particularly potatoes), avocado dip served in restaurants, wine, and beer. Molybdenum deficiency may cause sulfite sensitivity; sulfite oxidase is the enzyme that neutralizes sulfites and is molybdenum dependent. — Salt: Increased intake worsens bronchial reactivity and mortality from asthma. Bronchial reactivity to histamine is positively correlated with 24-hour urinary Na and rises with increased dietary Na. • Estrogen and progesterone: For women with severe asthma, consider decreasing hormonal fluctuations. Estrogen and progesterone are smooth muscle relaxants. Airways of premenopausal and postmenopausal women may respond differently to exogenous HRT and need assessment independent of this intervention. During premenstrual and menstrual phases, when hormones are low, asthmatic women have episodes and are hospitalized with decreased pulmonary function. Stabilizing hormone fluctuations (by pregnancy or oral contraceptives) improves pulmonary function and reduces need for medication. Liver detox and botanicals are safer methods to balance hormones. If these fail, natural HRT may be less risky (Textbook, “Asthma” and “Menopause”). • DHEA: decreased levels are common in postmenopausal women with asthma compared with matched controls. Transdermal 17b-estradiol (E2) and medroxyprogesterone acetate increase serum DHEAs in asthmatics, with no change in controls. Therapeutic benefit of DHEA in asthma is undemonstrated, but its importance to immune function suggests possible positive effects. • Melatonin: concern exists that elevated melatonin may contribute to airway inflammation in nocturnal asthmatics and inflammation in RA. In nocturnal asthmatics, peak serum melatonin is inversely correlated with overnight change in forced expiratory volume but not in nonnocturnal asthmatics or healthy controls. Release of melatonin is delayed in nocturnal asthmatics. Supplementation plus earlier bedtime may regulate late melatonin peaking and mitigate symptoms. Avoid giving melatonin to asthmatics, especially nocturnal type, until further study is completed.

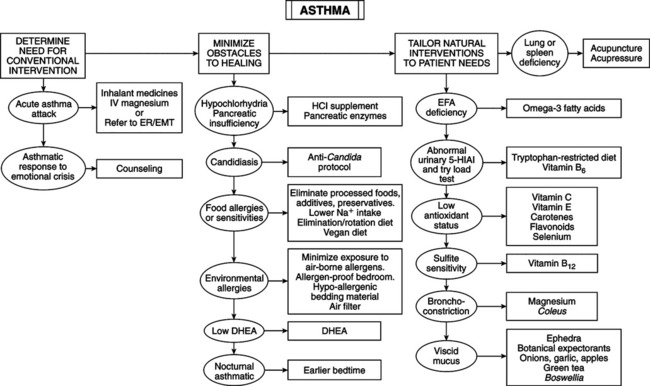

Asthma

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Causes

THERAPEUTIC CONSIDERATIONS

General

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine