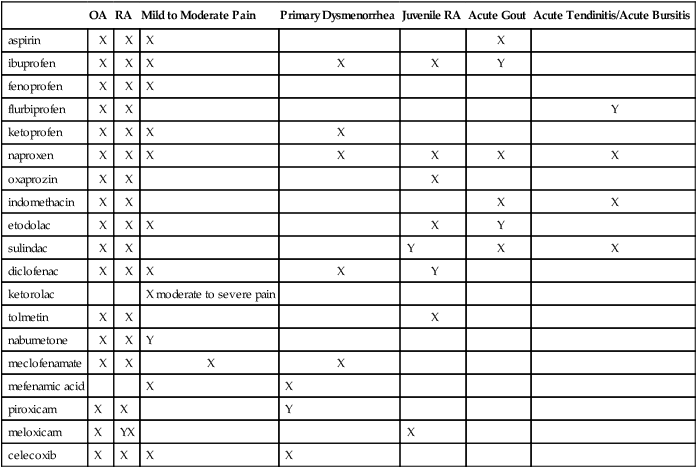

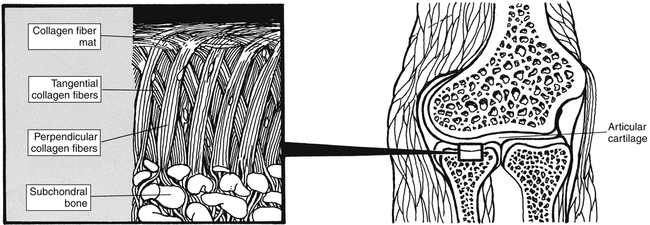

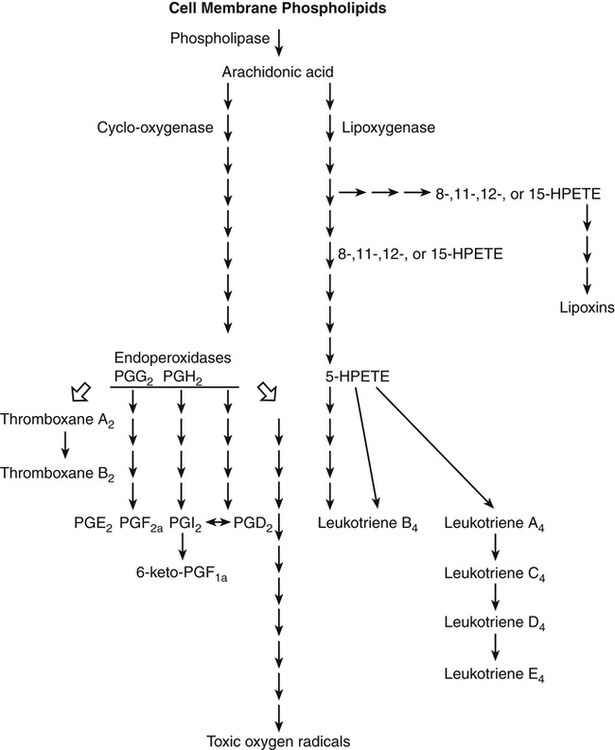

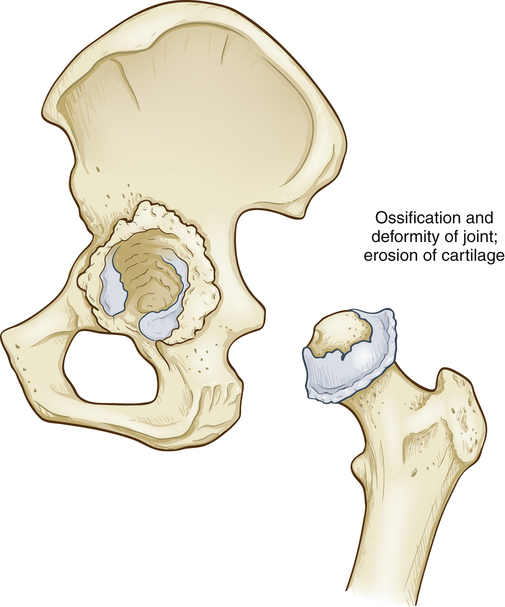

Chapter 36 In joints, the ends of the bones are capped by cartilage, and the joint structure is held together by a very tight capsule. A very fine membrane, the synovium, lines that capsule. The synovium normally stops at the point where the cartilage begins. The synovium does not extend across the whole joint; otherwise, trauma to the synovium would occur every time the joint was flexed (Figure 36-1). The tendons attach to the bones, and when the muscle contracts, the joint opens or closes. See Chapter 70, Immunizations and Biologicals, for a review of the immune system. Prostaglandins cause increased vascular permeability and neutrophil chemotaxis (movement), and they induce pain. Increased vascular permeability allows diffusion of large molecule inflammatory substances across cell walls into the site of inflammation. Prostaglandins are produced in the mast cell from arachidonic acid by the action of the COX enzyme and are classified into groups according to their structure. Prostaglandins E1 and E2 are active in the inflammatory response. Aspirin and NSAIDs act to block the COX enzyme from producing prostaglandins, thereby inhibiting inflammation (Figure 36-2). When an inflammatory process occurs, the synovium becomes lumpy. The synovium also starts to grow into and across the cartilaginous area, producing pits in the cartilage. At the same time, the tendon sheath that surrounds the tendon becomes inflamed, so motion of the joint is painful. If this process is not checked, ultimately, the ends of the bones are denuded and bone grates upon bone, with resultant eventual destruction of the joint (Figure 36-3). The inflammatory response is accompanied by symptoms of erythema, edema, tenderness, and pain. In OA, the articular cartilage degenerates, is roughened, and then is worn away. The body attempts to repair the lost cartilage, but the integrity of the new cartilage is inferior to that of the original, and the integrity of the surface of the cartilage is lost. Bone compensates by hypertrophy at the articular margins, forming spurs and causing lipping at the edge of the joint surface. The synovial membrane thickens, but it does not form adhesions. A low level of inflammation usually is present (see Figure 36-3). Salicylates and NSAIDs reduce inflammation by inhibiting the production of prostaglandins, prostacyclin, and thromboxanes in both CNS and peripheral tissue. They do this by blocking the COX enzyme. This major mechanism is involved in most of the effects achieved by salicylates and NSAIDs (see Figure 36-2) and may be responsible for the fact that the incidence of colon cancer has been found to be lower in patients who take ASA on a regular basis. • Brigham and Women’s Hospital: Lower extremity musculoskeletal disorders: a guide to diagnosis and treatment, Boston, 2003, Brigham and Women’s Hospital. • Patient education and exercise improve a patient’s well-being. • Topical NSAIDs, acupuncture, and tramadol are effective for pain relief in knee OA. • Glucosamine and chondroitin do not relieve most OA pain, but they may be effective in moderate to severe knee pain resulting from trauma or overuse. • Increased gastroprotective agent adherence in celecoxib treated patients is linked to reduced complications. Proton-pump inhibitors, high-dose H2-receptor antagonists, and misoprostol have been found to reduce the incidence of nonselective NSAID-induced UGI tract ulcer complications. • Begin with nonpharmacologic treatment. • The underlying goals of treatment are to limit the inflammatory process, protect the joint, and relieve pain. • Nonpharmacologic methods are important in all uses of NSAIDs. If a patient has moderate pain, consider starting NSAIDs at the same time that nonpharmacologic treatment is initiated.

Aspirin and Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Medications

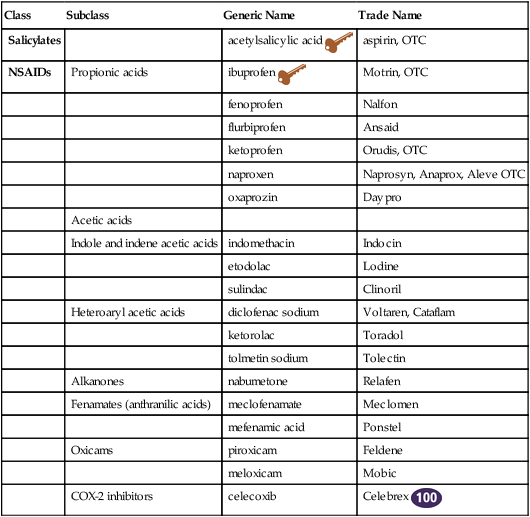

Class

Subclass

Generic Name

Trade Name

Salicylates

acetylsalicylic acid ![]()

aspirin, OTC

NSAIDs

Propionic acids

ibuprofen ![]()

Motrin, OTC

fenoprofen

Nalfon

flurbiprofen

Ansaid

ketoprofen

Orudis, OTC

naproxen

Naprosyn, Anaprox, Aleve OTC

oxaprozin

Daypro

Acetic acids

Indole and indene acetic acids

indomethacin

Indocin

etodolac

Lodine

sulindac

Clinoril

Heteroaryl acetic acids

diclofenac sodium

Voltaren, Cataflam

ketorolac

Toradol

tolmetin sodium

Tolectin

Alkanones

nabumetone

Relafen

Fenamates (anthranilic acids)

meclofenamate

Meclomen

mefenamic acid

Ponstel

Oxicams

piroxicam

Feldene

meloxicam

Mobic

COX-2 inhibitors

celecoxib

Celebrex ![]()

Therapeutic Overview

Anatomy and Physiology

Inflammation

Pathophysiology: Osteoarthritis

Mechanism of Action

Treatment Principles

Standardized Guidelines

Evidence-Based Recommendations

Cardinal Points of Treatment

Drug Choice

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Aspirin and Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Medications

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue