Chapter 9 Aromatic medicine

Aromatic medicine explained

• It is a therapy in which essential oils are used confidently and efficaciously in the most appropriate way for any presenting condition. The therapy is aromatic because it uses the aromatic, volatile molecules that constitute essential oils.

• It moves beyond the near-homoeopathic normal doses associated with aromatherapy massage and involves a considered response to a particular situation, balancing the presenting condition with a detailed knowledge of essential oils.

• It is built on knowledge of the therapeutic actions of the chemical components that make up essential oils, plus an understanding of the synergy within a single oil and the synergistic potential of blended oils.

• intensive because of the higher dosage than that used in massage

• intensive because it is more focused on a particular presenting condition

• intensive because of the application of chemistry as the principal tool used in oil selection

• specific because essential oils are engaged for a particular health improvement rather than general wellbeing

• specific because whole-body massage is not always needed or wanted, a more focused application being more necessary.

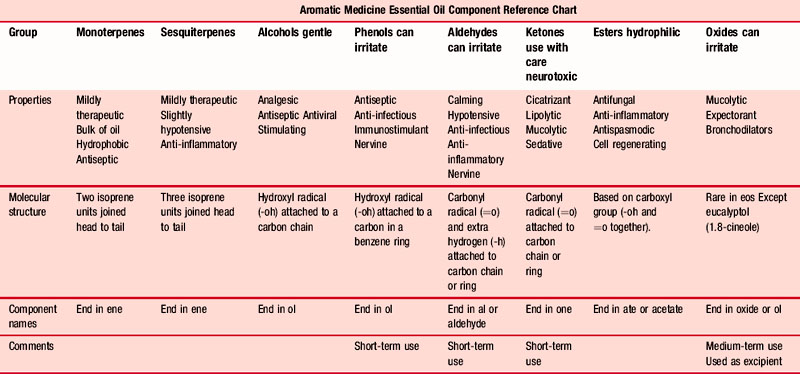

Beginning with essential oils

In aromatic medicine, treatment is based on the known and verifiable therapeutic effects of the chemical components found within the oils (Table 9.1), which means that practitioners need a sound working knowledge of the constituent parts of the oils to be used. They also need to be competent enough to work out what the components in the synergy of an essential oil mix will achieve – this can only be understood by detailed training in the chemistry of essential oils.

Table 9.1 Essential Oil Component Reference Chart Diagram (simplified) By kind permission of Penny Price Aromatherapy Ltd (www.penny-price.com)

Perhaps this approach is best illustrated with a recent example that caused a great deal of anxiety. Avian flu was followed by swine flu as a threatened pandemic. The few fatalities that ensued fuelled the hysteria that grew – disproportionately to the risk. The author, when taking a long-haul flight to China for a punishing teaching schedule of 7 days (including 10 flights), responded to the situation by researching the possible aromatic responses, the development in approaches 1–4 below showing the difference between the populist aromatherapy approach and that used in aromatic medicine (see Case 4.4 for the antiviral recipe used).

1. The general aromatherapy literature states that some essential oils are powerfully antiviral. Davis (2000 p. 308), for instance, suggests that bergamot, eucalyptus and tea tree may be used, but does not specify the oils, giving only the common names. These may indeed be effective, but there is no explanation as to how or why they work.

2. There is much more precision in the work of Pénoël and Franchomme. Franchomme (Franchomme & Pénoël 1990 p, 190) suggests that enveloped viruses respond to essential oils having a predominance of terpene-alcohols and phenols, whereas naked viruses respond to oils rich in terpenoid ketones. Pénoël is even more specific, suggesting that α-terpineol and the oxide 1,8-cineole should be administered. The oils suggested, in which these constituents are found, are Laurus nobilis [bay leaf], Eucalyptus radiata [narrow leaf peppermint] and Melaleuca viridiflora [niaouli].

3. Schnaubelt (1997 p. 98) states that terpenes enhance the immune system and metabolic activity by changing the receptors present on cell surfaces, and that new work is being undertaken on the reaction between sesquiterpenes and cell penetration.

4. Price and Price (2007 p.106) suggest that the effectiveness of essential oils may not be dependent upon any specific molecule, but rather on a property common to essential oils, perhaps lipid solubility.

5. The hypericin in Hypericum perforatum [St. John’s wort] has been indicated as inhibiting the development of a virus within an infected cell (Miller 1998). Hypericin is active against several viruses, including cytomegalovirus, the human papilloma virus, hepatitis B and herpes virus. This antiviral activity has been shown in the laboratory and animal studies, but not in human studies. The herb seems to work against viruses by oxidation and its antiviral effect is stronger when exposed to light (as when animals eat the herb). St. John’s Wort was studied in 1991 in people with HIV disease (Freeman & Lawlis, 2001, 415), where the doses were much higher than for treating depression. Patients were given intravenous doses of purified hypericin, but the study was stopped when every white-skinned patient in the trial became very sensitive to light. They developed skin rashes and some could not go outside until after they stopped taking hypericin. The one black-skinned patient did not have this reaction.

It is clear that essential oils are useful in the prevention of viral infection and in its treatment. Reflecting on the research, it appears as if essential oils are able to inhibit the absorption of a virus into a cell, and also to inhibit the reproduction of a virus once it has taken over a cell. On balance, the essential oils most useful are those with a predominance of 1,8-cineole and a significant presence of α-terpineol (although as has been seen, opinion varies and some viruses respond better to some oils than others – see Table 4.5 Ch. 4):

Given that viruses are contagious and very inventive in finding hosts, every care must be taken to prevent airborne infection and infection from contact. Diffusing an oil blend using a vaporizer is the best form of prevention. A blend of these oils added to a hand-wash would give further protection. If a viral infection has become established there are many proven and efficacious responses using essential oils, particularly to herpes simplex 1 and to the influenza viruses (Stephen 2010).