A Scientific Approach

Early in the sixteenth century, Nicolaus Copernicus carefully observed the movements of the planets and stars and formulated the belief that, contrary to the established view that the Earth was the centre of the universe and that the Sun, Moon and planets circled around it, the Earth was revolving and that the planets moved around the Sun. Galileo Galilei supported and extended this explanation (or theory) some half a century later. These early astronomers observed and described a phenomenon (the movements of planets) and then sought an explanation as to why the phenomenon occurred. Their curiosity extended to questioning the underlying reasons for the phenomenon, and to providing an explanation which linked observations to the underlying causes.

The hallmark of scientific reasoning is that phenomena and events are understood in terms of their causes. A scientific experiment attempts to manipulate the postulated causes of a phenomenon (called the independent variables), and then to see if the phenomenon (called the dependent variable) responds to the manipulation. We conduct many mini-experiments in the course of our everyday lives. For example, we notice that the tomato plants at the back of the greenhouse are not as tall as those at the front. We make a guess (a hypothesis), based on our knowledge that light is essential for plant growth (gained from earlier experiments), that the tomatoes at the back are deprived of light when compared to those at the front. To test our hypothesis, we move the smaller plants to the front and then wait to observe the effect on the dependent variable, height. If growth rates improve, we might feel our initial hypothesis is confirmed. If there is no change in relative height, we would be forced to review the initial hypothesis. Was it lack of water that caused the stunted growth? Were the tomatoes at the back a dwarf variety? Further experiments are thus suggested by the initial results, with control of these new factors or variables. This everyday experiment is not a true scientific experiment as it lacks the rigour necessary in a scientific methodology; for example, height would have to be measured very precisely both before and during the experimental manipulation of the factors (or conditions). But it is an experiment in that an idea or hypothesis is first developed and then tested by seeking objective evidence to determine its truth or falsehood.

A scientific ethos, with its emphasis on seeking the underlying reasons for events, suggests a powerful approach to combating forms of pathology. In intervening to reduce or eliminate deviation from a normal state, the identification of the causes of the pathology, and then the elimination of those causes, suggests a highly effective way to reduce abnormality. This is the approach adopted by the medical sciences in tackling disease. The medical sciences seek to restore the individual to a state of health by eliminating the source, or the aetiology,1 or cause, of disease. This may involve the study both of the direct cause of disease (such as a particular virus), as well as the predisposing factors which lead to the disease (i.e. those factors in the body or the environment which make the body susceptible to a disease, such as a particular lifestyle or diet). The value of this strategy is indicated by the degree to which it has been extended to deal with other types of pathology – and here we use ‘pathology’ in the extended sense defined in Chapter 1 as ‘deviation from any assumed normal state’. Attempts to reduce problems such as crime or truancy may often involve identifying the source of the behaviour, such as unemployment, poor housing, or youth boredom.

Let us take an example from the medical world of how the approach of eliminating causes operates. The patient is a 3-year-old boy who complains of earache. His parents also report that they have noticed a degree of hearing difficulty over the previous few days. The doctor, in taking a medical history, discovers that the child has recently had a severe head cold. At this point the physician might already form a hypothesis of what might be wrong with the patient. Often during a cold, a tube running between the back of the nose and the ear (the Eustachian tube – details of the anatomy of the ear can be found in Chapter 4) can become blocked with mucus. Subsequently the mucus can become infected by bacteria. This causes an expansion of the mucus and pressure on the eardrum. Eventually the pressure may cause the eardrum to burst. The doctor could seek evidence to confirm or reject the hypothesis by a physical examination of the patient, focusing especially on the state of the eardrum. If the doctor observes that the eardrum is red and inflamed, or perhaps already perforated and with discharge leaking from it, the diagnosis would be of ‘middle ear infection’. The cause of the abnormality is bacterial infection, and in order to attack that cause, the physician might prescribe an appropriate antibiotic.

Let us now take an example of the language pathologist using a similar approach – of seeking the cause of the disorder – in order to determine the best line of treatment. Peter, aged 3, is saying little more than a few words and phrases. He is referred by his family doctor to a local speech and hearing clinic. The language pathologist makes an initial assessment of Peter’s language ability and concludes that there is indeed an abnormal development of language, compared with other children of Peter’s age and background, and so there is a diagnosis of ‘language delay’ (see p. 151). The cause of the disorder will be investigated through taking a case history from the parents. Factors of interest would include the history of the pregnancy and the birth. Here the clinician is attempting to identify if the mother suffered any illnesses during the pregnancy which might have affected the normal development of the embryo. The birth history could provide information on whether there was any possibility of damage to the child at birth, for example, through oxygen deprivation (or anoxia). The case history might also reveal if there is a family history of language disorder, illuminating genetic or environmental factors in the disorder. Other possible medical bases for the problem might also be considered: Peter’s hearing might be tested; he might be referred to a paediatrician for a thorough medical examination. These investigations may indicate a clear medical cause, such as a hearing impairment. But what if everything is normal in medical terms? The search for a cause of the disorder might switch to the investigation of aspects of Peter’s behaviour. He might be found to be a distractible, hyperactive child, who is unable to pay enough systematic attention to his linguistic environment to be able to learn from it. A psychologist’s opinion might be sought here. Or perhaps Peter comes from a home background where he has been given little chance to learn from his environment – a social explanation for the problem.

A case such as this illustrates how a language pathologist uses the approach of seeking the causes of a disorder in order to understand the problem and to suggest ways of tackling the disorder. The search for cause is likely to encompass medical, behavioural and social–environmental considerations and, where a plausible source of the disorder is identified, the first strategy is to eliminate or ameliorate the causes. Hearing loss can be treated through elimination of ear infections and surgical procedures, and residual hearing impairment might be ameliorated by the provision of appropriate hearing aids. Attention problems can be tackled through behavioural programmes that assist the child to learn how to pay sustained attention. Such problems can also be treated with pharmacological intervention, although such an approach is sometimes controversial. If an environmental cause is suspected, the parents might be the target of intervention; they could be taught how to structure the child’s physical environment and their own behaviour in ways that would maximize the opportunities for language learning – an approach which is sometimes described as ‘parent skilling’.

This example illustrates how the language pathologist’s concerns in using a medical approach may extend to both medical and behavioural components of a disorder. We shall now consider how the medical and behavioural sciences have contributed to the theory and practice of language pathology.

Aspects of the Medical Approach

Let us look in a little more detail at the medical approach, which is the older and more revered of the two. The example of the child with a language delay reveals the extent of the influence of medical practice on both the vocabulary and the procedures or process of language pathology. This process operates as follows. We have a difficulty which is noticed either by ourselves or others. We go to a clinic and we become patients. We tell the clinician about the difficulty, thus providing the doctor (or language pathologist) with subjective evidence about the nature of our condition. Those aspects of the difficulty which lead to our complaints are known as our symptoms. The clinician takes a case history in which an attempt is made to extract from us everything that could have a direct or remote bearing on the presenting condition. There is then an examination, where the clinician aims to provide objective evidence (or signs) about the nature of the condition. Taken together, the signs and symptoms of the problem enable the clinician to arrive at a judgement concerning the nature of the difficulty. This judgement, and the process that led to it, are known as diagnosis. To be more specific, the clinician makes a selection from a set of possible hypotheses about the disease; by comparing one set of signs and symptoms with another, the aim is to reach a hypothesis which would explain most satisfactorily the present condition of the patient. A more precise name for this technique is differential diagnosis.

Once a diagnosis has been made, a course of treatment may be begun. Alternatively, the patient might be referred on to a specialist clinic either for further assessment or for a course of specialized treatment. At the end of the treatment, the patient’s progress is reviewed and, if the condition has been resolved satisfactorily, the patient will be discharged. Some disorders can be resolved (they have a good prognosis), leaving the patient with no residual deficits, as in the example of the child with a hearing loss due to a middle ear infection; but this is not always the case. Other disorders have profound and long-term effects on an individual’s functioning. One such example would be the genetic disorder, Down’s syndrome.2 The individual is born with an extra copy of chromosome 21 (hence the disorder is also known as trisomy 21). Although medical intervention to correct genetic abnormalities (often called gene therapy) has now begun, this work is in its infancy and offers treatment for conditions in which there are faulty genes, rather than extra chromosomes as in the case of Down’s syndrome. This genetic disorder cannot be remedied: we cannot ‘cure’ it. Knowledge of Down’s syndrome tells us that we can expect a level of intellectual or cognitive functioning which is below the usual level. This is important in planning any treatment. In setting targets for treatment, we cannot demand that the child suffering from Down’s syndrome should perform at the same level as a normal child; rather we have to adjust targets, with the aim of maximizing the child’s learning potential. Identifying a likely prognosis is important, therefore, in deciding on the goals of the treatment programme. It is also important that patients and their families are aware of the prognosis – is a ‘cure’ being offered, or is the clinician hoping to maximize abilities but within clearly defined limits?

Although there are many conditions for which the medical strategy of ‘eliminating causes’ is not a practical basis for intervention, the medical sciences have contributed a body of knowledge which provides an important frame of reference for analysing communicative disability. There are a number of branches of medicine which are of particular relevance to the language pathologist. The foundation subjects of the medical sciences – anatomy and physiology – are a necessary part of the curriculum in the education of language pathologists (see Chapter 4). Certain conditions – for example, disorders of the voice – can be properly understood only if grounded in knowledge of the structure (anatomy) and function (physiology) of the respiratory and voicing systems.

A number of medical specialisms are of particular relevance to language pathology, and clinicians may often work alongside medical practitioners from these fields. The specialisms of particular importance are paediatrics, neurology, and ear, nose and throat (ENT) medicine (the latter sometimes called otorhinolaryngology). Paediatrics is concerned with diseases and conditions of childhood. A considerable number of children who are referred to language pathologists will at the same time be seen by a paediatrician. They will include children with overt conditions such as Down’s syndrome or cerebral palsy, but also children who for no apparent reason are failing to thrive and to reach the milestones of normal development within a normal time-band. Neurology is the branch of medicine which deals with diseases and conditions of the brain and the system of nerves which links the brain to all parts of the body. Like most fields of medicine, it can be subdivided into further specialisms, such as paediatric neurology and neurosurgery. Individuals who have experienced conditions such as a stroke, Parkinson’s disease, or cerebral palsy may often be referred to language pathologists from neurology clinics. ENT medicine addresses diseases and conditions of the bodily structures involved in the production and hearing of speech. For example, conditions which affect the normal functioning of the ‘voice box’, or larynx, will result in the involvement of clinicians from both ENT medicine and speech and language pathology in the management of the disorder.

Language pathology has inherited an important body of knowledge and sets of procedures from medicine. With this inheritance has come traditional ways of approaching patients and their impairments. But there now exist many challenges to these conventional ideas about tackling disease and the nature and process of the doctor–patient interaction. Medical science, given its focus on causes of disease, might define ‘health’ as ‘the absence of disease’. But is this an acceptable definition? Let us imagine a speaker with a stammer or a fluency disorder which results in disruptions to the flow of speech by repetition or prolongation of sounds (see p. 188). After a programme of intervention, this individual learns strategies to control the stammer to such an extent that most of the people with whom he or she subsequently interacts would not characterize the speaker as showing any form of communicative impairment. Similarly, objective assessments made in the clinic show levels of speech dysfluency indistinguishable from those of normal, or non-impaired, speakers. This evidence might suggest that the dysfluent speaker is ‘cured’. There is now an absence of communicative impairment and so the speaker can be regarded as being in a state of ‘communicative health’. But what if this individual does not believe himself or herself to be cured, and that at any moment the stammer will return and cause embarrassment and communicative failure? As a result, the ‘cured’ stammerer avoids as many communicative exchanges as possible and life becomes organized around the avoidance of situations which involve talking, influencing employment choices, social contacts and such everyday activities as the place to shop (for example, the supermarket is to be preferred to the local delicatessen if one wishes to avoid speech). Although this speaker might show communicative ‘health’, in that there is an absence of evident impairment, the degree of control of lifestyle in order to avoid speaking would suggest that he or she lacks communicative ‘well-being’. A definition of health in terms of presence of well-being is probably more important than the negative definition of health as the absence of disease or impairment.

The medical approach is also challenged by the increase in long-term (or chronic) disorders in modern societies. Paradoxically, this increase is partly due to the success of the medical sciences in tackling many conditions which previously would have been fatal. Advances in intensivecare medicine have permitted individuals with severe head injuries to survive, albeit with serious disabilities. Progress in neonatal intensive care means that very premature babies can survive, although again a proportion of these babies may go on to experience a range of cognitive and other physical problems. The control of several diseases through the development of effective antibiotics, or through early detection programmes such as breast or cervical cancer screening, means that more people survive into old age. Although old age is not inevitably accompanied by physical decline, there are chronic conditions linked to ageing which have a substantial impact on the quality of life. Medical science has met the challenge of chronic illness through the development of palliative medicine – that is, intervention which focuses on alleviation of symptoms, and particularly on pain relief, without the elimination of the underlying cause. In instances of chronic communicative disability, such as the linguistic problems that might follow a severe stroke, there is now recognition that the management of the condition cannot be motivated only by the single strategy of eliminating impairments. Proper and total management would also include the consideration of ways of maintaining quality of life, for example through the maintenance of social contacts via support groups, both for the disabled persons and those who care for them.

Chronic disease has presented the medical sciences with new challenges. In addition, the nature of the relationship between the doctor and the patient (or therapist and patient) is also facing changes. In the past, a consultation between a professional and patient was one between an expert and a supposed novice, which led to inequalities of power and authority within the relationship. Increasingly, however, patients are no longer novices, and in some situations may know more about their condition than their medical practitioners. This is particularly the case in many chronic conditions where there now exists large amounts of information in various published media – books, health magazines and patient information groups on the Internet, together with self-help groups and charities, all of which act to make patients more knowledgeable about their illness. There is a trend in many areas of health planning to involve the users of a service in its development and management. The patient is likely to be involved to a greater degree in decisions regarding the treatment of a disorder, with ‘informed consent’ being a prerequisite of any medical intervention. This trend of patient involvement is sometimes termed empowerment, to reflect the shift from traditional patterns of power and authority within clinician–patient interactions.3

There are other limitations of the medical approach. Often it provides only the beginnings of an explanation of a communicative disability, and often no explanation at all. For those communicative disabilities where there is no evident medical condition involved, such as disorders of speech fluency or stuttering, the medical sciences may contribute little to the understanding of the disorder. And even where a medical condition is apparent, it is important to remember that the language pathologist deals with disruptions of behaviour. The assessments and treatments which the language pathologist administers are directed at behaviour. Radiological imaging of body structures, tissue biopsy, and laboratory analysis of body fluids such as blood or urine are not part of the language pathologist’s assessment armoury. Treatments are also behavioural – for example, when assisting the patient to learn new vocabulary or sentence structures. The language pathologist is not directly involved in drug or surgical interventions. The medical approach gives an indication of the individual’s probable limitations in responding to treatment (part of medical prognosis) when the individual is suffering from some identifiable medical condition, but it does not give any positive guidelines as to how the treatment should be carried out. For example, if John has been diagnosed as suffering from a hearing impairment, the process of medical diagnosis will indicate the limitations of John’s hearing, and the possibilities of recovery, and these facts will be important to the clinician who must collaborate in a remedial programme; but the medical information by itself does not tell the clinician or teacher what language structure to teach first, or how to move from one type of linguistic structure to another. Likewise, we may know which area of a person’s brain has been damaged following a stroke, and having this knowledge may give us an idea as to how far the patient will respond, and how far we may expect treatment to be successful; but this knowledge does not necessarily tell us which linguistic structures to rebuild first. To obtain help on such matters, we need an alternative way of describing linguistic disability, and one which addresses the issues of behaviour in a more direct way.

Aspects of the Behavioural Approach

The medical approach is in principle a familiar one. Several of its terms (such as ‘symptom’ and ‘diagnose’) have come into popular use. The other main approach used in language pathology is by no means so familiar. It is a more recent development, deriving from the progress made in such twentieth-century subjects as psychology, sociology and linguistics. These subjects can be gathered together under the umbrella of the ‘behavioural sciences’, as they share the characteristic that they study the behaviour of humans and other animals. It is this general sense which is intended when we talk of the ‘behavioural approach’ in language pathology.

The main problem with this label is that it might trigger off the wrong associations in the mind of a reader who knows about certain important themes in psychology; so perhaps we should begin by commenting on what the label does not refer to. In particular, it does not refer to the specific school of thought in psychology (and also in philosophy) known as ‘behaviourism’. This school, associated in America with the names of J. B. Watson, Clark Hull, and B. F. Skinner, and in Russia with Ivan Pavlov, restricts the study of humans and animals to their observable patterns of behaviour, ignoring any mental processes which are not directly observable and measurable, e.g. such notions as consciousness and introspection.

Students of language pathology share the behaviourist psychologist’s concern to describe accurately the observed linguistic patterns in communicative behaviour, and the analytic techniques of linguistic science assist in this. But language pathologists do not restrict their study to these patterns; they frequently draw upon theories of the types of mechanisms within the human mind which are responsible for generating both normal and aberrant language behaviour. These invisible mental systems might include constructs such as a ‘mental dictionary’ or ‘lexicon’, which is a store of the words that a particular speaker has learned. Alternatively, there may be reference to operations performed by a ‘parser’ – a hypothesized process which ‘chunks up’ heard sentences into small constituents for subsequent analysis. The operation of the parser is thought to be seen in some ‘garden-path’ sentences, where the language decoder is led up the garden path and makes errors in the chunking of a sentence. For example, the sentence, The hungry dog the conscience of the rich, may require you to read it twice before you decode it accurately. (Your ‘parser’ might have mistakenly categorized dog as a noun, and as part of a noun phrase the hungry dog, instead of its actual verb status in this sentence.) These hypothesized mental processes and stores – lexicons and parsers – are not directly observable. Their existence can be inferred only from observable behaviours, and errors such as the garden-path sentence are often informative in developing theories of the mental mechanisms which underpin language behaviour. Errors occur relatively infrequently in normal language, but with great regularity in disordered language, and hence there has been considerable interest in pathologies of language from scientists concerned with developing theories of the mental processes which underpin language behaviour.

The ‘behavioural sciences’ are therefore distinct from ‘behaviourism’, which is a specific school of thought within psychology. In this book there will be two main sources of information within the behavioural approach. First, as the book is about (abnormal) language behaviour, linguistics will be one main source. Psychology will provide the second, and in particular the subfields of psycholinguistics (which, as its name suggests, provides a bridge between linguistics and psychology) and cognitive psychology. Other specialisms within psychology are also important, including developmental psychology and neuropsychology (see further p. 56).

In what way can linguistics and branches of psychology contribute to the study of communication disorders? What is a behavioural approach? At the core of this approach, not surprisingly, is a focus on the patient’s behaviour. Detailed descriptions and analyses of the patient’s behaviour are produced and the profile of behaviours is then compared to what is identified as normal. Behaviours of the patient which are markedly discrepant from normal are then targeted for treatment, which consists of moving abnormal behaviours, in gradual steps, towards more normal patterns. Let us return to our example of Peter (p. 25), the 3-year-old with abnormal language development. Despite extensive investigations, we may have failed to identify any obvious cause for this problem. Peter appears to be a child of normal intelligence, with no behavioural problems other than his language development. Medical investigations have revealed no physical abnormalities, thus excluding problems such as a hearing impairment or brain damage. His home environment is all that we would hope for in terms of the quality of his relationship with his parents and the opportunities for learning. At this point we have to accept that Peter’s difficulties have no obvious cause, and concentrate our efforts on doing something that will assist him in learning language. In order to plan treatment, a detailed analysis of his behaviour is needed. We need to identify what Peter can and cannot do, and what he does incorrectly. Linguistic science provides us with a variety of models for analysing communicative behaviour, and the speech and language therapist will need to be familiar with these in order to produce a description of Peter’s language. Armed with this analysis we can then compare Peter’s behaviour to that of other 3-year-olds and so identify his areas of strength and deficit. This may sound an easy procedure, but the identification of what is normal in any human behaviour, and in particular in the behaviour of young children, is difficult because of wide variability in the pattern of even normal development. However, if we are reasonably confident of our normative data, we can then begin treatment by gradually moving Peter’s abnormal behaviour towards what has been identified as normal.

This example shows that a behavioural approach is essential to treatment planning for the speech and language therapist. It is not an alternative to the medical approach, as each approach focuses on different aspects of the diagnostic–treatment process of language pathology, and so both are essential influences.

An issue which is fundamental to the illustrative case of Peter is that a behavioural approach rests upon the elicitation of a sample of communicative behaviour and subsequently its description. How easy is it to carry out this process of investigation? In fact, it turns out to be extraordinarily difficult, for a mixture of practical and theoretical reasons. Let us look, first of all, at the basic task of describing the patient’s linguistic behaviour. Put yourself in the position of the clinician. The first thing you must do is obtain a sample of the patient’s linguistic behaviour which is typical – a ‘representative sample’. The patient has come to the clinic in the local hospital, perhaps for the first time, and meets you for the first time. How typical will the patient’s language be? How typical would your language be – faced with unfamiliar faces and surroundings? There is obviously a difficulty here, in that it is essential to develop a rapport with patients before you can feel confident that the kind of language they use to you is similar to that which they use at home and with friends. Indeed, in very problematic cases, it may even be that patients choose to use no language to you at all, to begin with. This is often the case with young children, who may take a long time to get used to you – several weeks if you are seeing the child only once or twice a week, for half an hour at a time. And even when children do begin to show an interest in communicating with you, it make take even longer before you feel sure that you have a clear sense of the strengths and limitations of their linguistic system. One therapist, after spending a great deal of time in an initial session trying to elicit simple one-word, ‘naming’ sentences from a child by showing him a picture book, and asking him to say what the objects were in the pictures, was somewhat startled to hear him outside the waiting-room informing his big brother ‘me can do them word in there’! He had shown no sign in her presence of any ability to use such a lengthy sentence, nor had his mother given any hint that he sometimes at home came out with such things.

This issue – of the ‘ecological validity’ of the data sample collected – is one which is common to many branches of the behavioural sciences. Human behaviour will alter with the context or environment in which it occurs (consider, for example, if a sample of your language behaviour collected when talking with friends in a pub would be representative of your communicative behaviour in a tutorial). If an individual’s behaviour is recorded in a laboratory or a clinic it may well be behaviour representative of performances within this highly constrained context. But if the behavioural scientist is interested in making generalizations from the laboratory behavioural sample to behaviour in other contexts, there is a major question of the validity of such generalizations. This issue is a particularly acute one for the speech–language clinician. Communicative behaviour changes very markedly across contexts (see p. 18), and the clinician is interested to generalize from clinic-based language behaviour to the communicative behaviour typical of everyday interactions with family, friends, teachers and work-mates.

But let us assume that you have solved this initial problem, and are faced with a patient whom you have come to know, and who is at ease in your clinic – or perhaps you are at ease in the patient’s own home (i.e. you have made a ‘domiciliary visit’). What are you going to talk about? Or, putting this another way, does it matter what you talk about? It does indeed. Some patients, for instance, find it particularly difficult to talk about certain areas of vocabulary (such as parts of the body, or colours). Others find it possible to talk only about what is going on in the room around them; they are unable to discuss absent’ topics, such as what happened the day before, or what will be on television this evening. Some patients find it difficult or impossible to answer very general, ‘open’ questions such as ‘What’s happening in the picture?’, but are able to answer a question where: certain alternatives have been presented clearly before them (e.g. ‘Is the man running or jumping?’). It is not usual to think of your conversation with someone as being a ‘task’ to be handled, but that is exactly what you are doing with linguistically disabled patients. And part of the clinical skill will be to make the patients’ task of understanding your language as easy as possible, by trying to get your language at exactly the right level so that they will understand and respond. It is not an easy level to find. If you do not simplify enough, your patients may get disheartened. If you simplify too much, they may think you are talking down to them. ‘Why does everyone talk to me as if I were stupid?’ one stroke patient once complained. ‘Why does everyone talk to me as if I were deaf?’ complained another, deaf, patient, with equal feeling!

But let us assume that you have sorted out this problem, and have decided what kind of conversation you want to elicit from your patients – whether a carefully pre-planned dialogue, or spontaneous chat, or whatever. How are you going to record your conversation? Remember that you want to analyse this recording later, so a great deal of thought must be given to technical and practical matters. Where are you going to put the tape-recorder? Will patients be upset if they see it? Will they want to destroy it (usually only a problem with children)? And again: Where will you put the microphone? If you want to hear not only what the patient says, but also what you say, how are you going to position the microphone so that you pick up both voices well – and at the same time exclude as many background noises as possible, such as passing traffic, children in the room next door, and the like? While the recording is in progress, how will you make notes so that the events in the room, invisible to the audio tape, will be remembered afterwards? So often, one listens to a tape several hours later, and encounters a particularly puzzling piece of language – or an even more puzzling silence – and cannot recall what the patient was doing at the time. One way around this problem would, of course, be to video-record the conversation. This is sometimes done, but what is the effect on your behaviour when someone points a video camera at you? Are you at your most spontaneous and natural? If our aim is to record behaviour which is typical, the use of video may sabotage this goal. Despite these difficulties, video-recording has its place – particularly in recording the non-linguistic components of an interaction.

But let us assume that you have solved the problem of keeping an accurate record of the conversation, and of the context in which it took place. Your patient has gone home, and you now have all the time in the world to listen again to the tape and analyse what is there. Unfortunately, this ideal world rarely exists. When one patient leaves, the next may be waiting outside. And yet others waiting behind. It is a problem which many clinicians solve by reorganizing their case load so that, at least for the more problematic cases, they give themselves some opportunity to carry out the careful description of their patients’ behaviour that is a prerequisite of systematic treatment. But for many others, either for lack of training or of opportunity, they must be satisfied with much less.

But let us assume that this problem has been solved, and that somehow time has been made available for you to analyse the patient’s language. How will you set about doing this? The right technical equipment, if this is available, will facilitate matters. When you consider the many tiny details that distinguish the various sounds of speech from each other, or the speed at which sentences are often spoken, with words being run together in various ways, it will be evident that making a description of what is on the tape will not be a straightforward matter. One device which helps is known as a ‘tape-repeater’. This is a loop of tape attached to a tape-recorder. When the appropriate switch is pressed, it repeats indefinitely the last five seconds or so of tape, thus allowing you an opportunity to hear a problem utterance over and over. Only by dint of such repeated listenings can you sometimes be sure that you have written down exactly what was being said – and in fact in no conversation is it ever possible to get everything right. The tape-repeater, at least, ensures that whatever can be transcribed, will be, with maximum saving of time. But in addition to such technical assistance, you will need to have had considerable training in the skills of transcribing and describing speech.

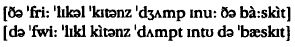

Note, first of all, this distinction between ‘transcription’ and ‘description’. A transcription, in its commonest use, is a precise notation of all the sounds used in speech. It is technically known as ‘phonetic transcription’ (see p. 44), and it has to be able to cope with all the possible sounds that the human vocal apparatus can produce. It is obvious, therefore, that our everyday alphabet will not have sufficient letters in it to enable you to write down all these possibilities. Special symbols and accents have to be used, and the sounds they reflect have to be recognized, so that the whole of a patient’s speech can be written down precisely and consistently. This process can be illustrated by comparing the way in which two patients said the sentence: ‘The three little kittens jumped into the basket’. Without knowing what the symbols mean, it will none the less be obvious that two very different types of pronunciation are involved, neither of which would it be possible to distinguish using the standard alphabet.

Each symbol, of course, is only a shorthand way of referring to the way a sound is made. If we were to write out in full everything we did with our vocal organs when we uttered the sound b, it would take up a great deal of space. The symbol [b] is simply a convenient way of summarizing all this information.4

It is often the case, however, that if we compare the transcription made by even very experienced transcribers of speech there can be considerable differences in what they record. This is known as low interrater reliability. This is particularly the case if it is severely disordered speech that is the object of the transcription. It is also possible to find low intra-rater reliability in transcriptions (i.e. given the same speech sample, there are considerable discrepancies in the transcriptions produced by the same individual on two occasions). Low intra-rater reliability is often an indication of insufficient training or perhaps lack of practice of transcription skills. Because of the difficulties with the reliability of transcriptions of speech, such transcriptions can be supplemented with objective instrumental means of recording speech activity. Equipment such as a nasometer (which measures the amount of air flowing through the nose), electropalatograph (which records contacts between the tongue and the roof of the mouth), and spectrograph (which captures the acoustic characteristics of the speech sound wave) are available in some speech clinics. These devices are not an alternative to transcription; rather, the findings of instrumental investigations need to be integrated with the auditory analysis. The equipment is expensive and its use demands considerable expertise on the part of the clinician. Inevitably, both factors combine to limit the routine clinical use of such instrumentation.

The term ‘transcription’ is also used in a more general sense, referring to the writing down of what is heard on a tape, but without giving phonetic details – an orthographic transcription. This is in fact the most convenient form of transcription when doing an analysis of grammar, vocabulary, or conversational interaction, where phonetic details would be obscuring or irrelevant. An example of an orthographic transcription, giving no phonetic information, is shown on p. 45. There are also ‘mixed’ transcriptions, in which a limited amount of phonetic detail is included: an example is given on p. 183. There is no one ‘perfect’ transcription. When working clinically you need to choose a transcription which suits your purpose.

All transcriptions are a form of description – in the sense that what they do is make a permanent record of the sounds of speech. But when we talk about description in relation to grammar and other areas of language, rather different considerations apply. In particular, a grammatical description will require the mastery of a terminology which allows you to identify the way in which patients build up their words, phrases and sentences. In grammar, you need to be able to notate the various patterns of construction that patients use, and sometimes quite a complex-looking apparatus for labelling sentences is involved. Learning to recognize parts of sentences as clauses, phrases, subjects, verbs and objects, and such like, is as much an aspect of linguistic description as is the phonetic description summarized in the notations above (see further p. 44).

We have only just begun the task of carrying out a description of our patient’s linguistic behaviour, but already it will be apparent that the operation is an exceedingly complex one, which requires considerable professional skill if it is to succeed. Obviously, too, we must know a great deal about the nature of language before we even begin – for otherwise how should we know what to look out for, in making our description? It is not enough simply to observe patients in order to describe their behaviour. In fact, observation without information is valueless. Imagine your reaction if asked to go into a room and ‘observe’ someone, and to report back in five minutes. You would be confused, because you would not know what it was that we wanted you to look out for. The way people scratch their chin, or sniff, may be a noticeable feature of their behaviour – but are such points the ones that need to be noted? Presumably we do not want a detailed account of everything the person is doing, so your problem will be to decide which particular points are the important, or salient ones, for our purpose. So what is our purpose? What do we want to know? If we provide you with some information about this in advance – perhaps give you a set of guidelines to follow while carrying out your observation – you will feel much happier. At least then you will know what you are supposed to be doing, and be able to concentrate your skill in doing it. What, then, do you need to know in advance about language, that will enable you to see a pattern in the linguistic behaviour of the patient?

Linguistics

The first thing to be clear about is what is involved under the heading of ‘language’. What counts as language? We have already seen (Chapter 1) that language is not to be identified with the notion of communication. There are many forms of communication and only one of these is linguistic. Language is in the first instance auditory – vocal communication, i.e. listening/speech; in the second instance, it is the encoding of speech in the visual or tactile medium (as with reading/writing and some forms of signing). Language does not include non-verbal communication or extra-linguistic features such as voice quality.

This does not mean that the non-linguistic aspects of communication can be ignored. On the contrary, holism (p. 16) requires the clinician to understand the whole of the patient’s communicative system. Individuals with a severe disorder in understanding spoken language, which renders much of what they hear as incomprehensible, may still retain non-verbal ‘listening behaviours’. For example, they may orientate their body towards the speaker, watch the speaker’s face (sometimes called making ‘eye contact’), and give little nods and vocalizations such as ‘mhm’, which give the speaker the impression that the listener is engaged with and comprehending the conversation. These non-linguistic signals of active listening are of great communicative importance. Such individuals are likely to have greater opportunities for social engagement than equally linguistically impaired people who are unable to signal active listening. But such behaviours are no substitute for language. Because such people are unable to decode the sounds, structures and vocabulary of the linguistic message, it will not be possible for them to contribute to the topic, to give their own opinion, or to introduce a new topic. To develop a full potential for communication it is necessary to come to grips with language sooner or later. Because of the great differences between language and other forms of communication in terms of productivity and duality of structure (p. 5), there is very little that can be carried over from knowledge of non-verbal communication into the learning of language.

Language is complex, and in order to understand its complexity, we need now to examine in more depth the question ‘what is language?’ and to look at the models of language that are used within the academic discipline of linguistics. In order for us to communicate, we must agree to use a particular means – a particular code, or language. And that means agreeing to a particular set of rules that govern the way in which the code, or language, is to be used. If we agree to use two flags in various positions around the body to signal letters, as in semaphore, then we cannot suddenly in the middle of a message start using three flags. The message would become uninterpretable, because we would no longer share the same system. And it is the same with language, though here the rules are more extensive and more complex. Unless we follow the same set of rules, linguistic communication is impossible. As a result of the process of learning our mother-tongue, each of us has developed an internal sense of what are the regular patterns of our language. It has largely been an unconscious process – though sometimes it becomes an explicit one, as when in school we are taught to use certain constructions and avoid others. And it remains largely an unconscious ability. Without formal training, people do not have the ability to define the rules governing the ways utterances may be constructed in their language. And yet everyone knows the patterns which lie behind these rules, for they are able to recognize acceptable utterances in their language, can correct unacceptable ones, and even pass judgement on their typicality or appropriateness. For example, here is a list of six nonsense words, three of which have been constructed according to the rules of English pronunciation, and three of which have not. It is not difficult to distinguish the two types:

Working out why some of these sequences might turn up in English, and why some do not, however, is not a simple task – especially when you consider the whole range of the pronunciation system. Similarly, we can look at a set of sentences and decide which are acceptable and which are not. Here are some cases:

The job of attempting to define explicitly the rules which describe the construction of acceptable utterances in language is carried on as a part of linguistics, and we shall have to look more closely at what is involved in carrying out this task in due course (see p. 44, ff.). For the present, it is important simply to note that to learn a language is to learn the system of patterns and rules governing the way utterances are constructed, and it is our implicit knowledge of these patterns and rules which constitutes the real measure of our language ability.5 We should also note that it is of course possible for us to make mistakes and break these rules. The likelihood of violating language rules increases if we talk when extremely tired, or stressed, or inebriated. We will notice an increase in false starts and hesitations; we may begin a sentence but not complete it. We may have difficulties finding words and maybe make more ‘slips of the tongue’ (for example, ‘cup of tea’ emerges as ‘tup of tea’). At times then, our actual linguistic performance may not match up to our knowledge of our language.

We use our intuitions as evidence for the psychological reality of the rules we postulate for our language. For example, if in a grammar book you are told that there is an active voice and a passive voice for sentences in English, as illustrated by such sentences as The cat bit the dog and The dog was bitten by the cat, you might well ask, ‘How do we know that this is so?’ The answer is: if you reflect upon the meaning of these two sentences, your intuition tells you that they mean the same, and that moreover there are lots of other sentences linked just as these are (The man saw the car and The car was seen by the man, etc.). If you feel that these sentences are closely linked, then this is one of the things that grammar-book writers should tell the non-English-speaking world about – and they do so using the labels ‘active’ and passive’ as ways of summarizing all the sentences that share the characteristics of each of the two types above. A grammar, in this way, is seen as a formulation of the agreed intuitions of the native speakers of a language. One reason that would lead you to conclude that a grammar book was unsatisfactory would be if the book told you that it was all right to say such sentences as Cat mat the on sat the. It is, of course, unlikely that any grammar of English would do such a thing, but there are many less ridiculous cases over which there has been considerable controversy, e.g. should a grammar ‘prescribe’ that you should use such constructions as the man whom I saw …, or refuse to allow you to end a sentence with a preposition?6

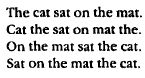

For clinicians this distinction between rules and usage, and the fundamental role of intuition in finding out about language, is of central significance. They too need to be able to distinguish what is idiosyncratic and casual from the underlying linguistic system in their patients. Their main concern is to ensure that patients learn rules for the language as a whole, and are not satisfied with using single sentences. It may not be too difficult a matter to teach patients to say The cat sat on the mat (e.g. the therapist might just get the patient to repeat the sentence, a word at a time); but what have patients learned about the abstract structure of that sentence? Do they realize that there are three main parts to that sentence (The cat/sat/on the mat), and that they could replace each of these parts with corresponding parts, to produce an inexhaustible supply of such sentences – the cat/dog/man/ … sat/walked/ran … on the mat/in the road …? This is a much more difficult task for therapists. But without access to these abstract rules of a language, patients are also denied access to the infinite creativity of language.

Once there is some agreement about the patterns and rules of a language, this body of knowledge can be used to evaluate the linguistic performance of the individual with disordered language. Clinicians work by eliciting and monitoring the patient’s linguistic behaviour and looking within this for the patterns of usage that might provide clues as to the nature of the underlying linguistic system. There are a number of broad possibilities regarding the relation of a disordered system to that which is present in the community to which the patient belongs. Sometimes it is evident that individuals are using a reduced version of the language heard around them. In other cases, individuals may have idiosyncratic systems: ‘they are doing their own thing’. This might occur if a language-disordered child is raised in a bilingual environment, and works out a language system which is based on an idiosyncratic blending of patterns from different languages. But children raised in a monolingual environment might also develop an idiosyncratic system because the hypotheses they form about patterns in the language that surrounds them are either incorrect or provide only a partial account of their native language.

A further possibility, and one quite common after brain damage in a previously normal adult speaker, is that there is considerable variability in the pattern of language behaviour. Sometimes the individual gains access to a relatively normal set of language units and the rules for their combination, and at another time this access is blocked. This results in large degrees of variability in the performance of the brain-damaged patient: at one moment a correct sentence is produced, and at the next speech output degenerates into fragments of sentences, containing many errors. In all these instances there is a need to obtain and then analyse a sample of the patient’s language and to identify the patterns that occur within the data. From the analysis, a hypothesis is formed, and treatment is a process of testing out the hypothesis. Again we see the influence of a scientific approach – rigorous methodologies for analysing data and a process of hypothesis formulation and testing. If the hypothesis is correct, then the patient will progress. If not, it is back to the drawing-board: more meticulous analysis, more formulation of hypotheses, more testing. It can be a long-term, laborious and altogether engrossing exercise, but its challenge is rewarded by progress in both human and intellectual terms.

Models of Language Structure

Let us assume that we have before us a sample of language ready for description and analysis. How should we organize our description of this linguistic material? A balanced and properly technical discussion of the kinds of model available would come from the field of linguistics. For present purposes, all we need to do is provide an outline of the main characteristics of a linguistic model relevant for clinical purposes, and as a perspective for the detailed discussion of pathologies in Chapter 5.7

In this model, an initial distinction is made between the notions of language structure and language use. Under the first heading is subsumed all the formal features of language, as directly observed in a spoken utterance (or its equivalent in writing). Most views of language classify these formal features into three main types, which for speech are usually referred to as phonology, grammar and semantics. These are said to be the three main ‘levels’ or ‘components’ of language. They may be studied in various orders: some linguistic theories begin with grammar, some with semantics or phonology. Basically, what is involved in each level is the following.

Phonology

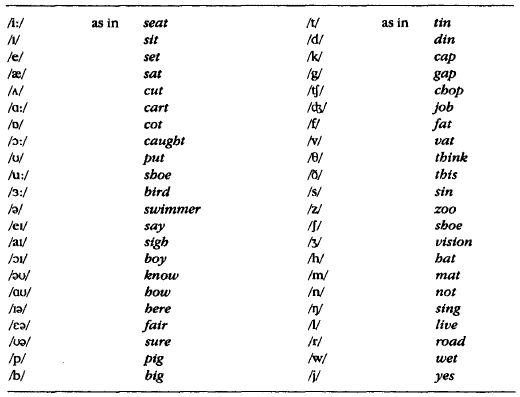

At this level, we study the way the ‘sound-system’ of a language (or a group of languages) is organized. The human vocal apparatus can produce a very wide range of sounds, but only a relatively small number of these are used in a language to express meanings. The sounds do this through being organized into a system of contrasts, the various words of the language being distinguished from each other by substituting one type of sound for another. For instance, pot is distinguished from got by the contrast between /p/ and /g/ at the beginning of these words. How many contrastive units of this kind are there in English? The answer depends a little on how you analyse what you hear, and what dialect of English you are studying; but in one influential account of southern British English, there are 44.8 We have listed these contrastive units, or phonemes, in Table 2.1, along with some examples, because it will be useful for illustrating disorders of phonology in Chapter 5. It should be noted that it is usual practice to transcribe phonemes in slant brackets (see further below). There are, of course, many variations in the contrasts listed in Table 2.1 which we have not referred to. For instance, when the contrast between /t/ and /d/ is made at the beginning of a word, it is generally more forceful than if it is made at the end of a word (compare tin/din and bit/bid). Moreover, the list gives information only about the way in which a word can be split up into a single sequence of phonemic units, or segments: big has three phonemic segments, for example, /b/ + /I/ + /g/. It does not give information about the constraints on the sequence and position in which phonemes may occur in a language. It was this knowledge which enabled you to decide that whereas vob is a possible word in English, vbo is not (p. 39). These restrictions on the sequence and position of sounds are called phonotactic constraints.

Also within phonology is the study of the way in which words (and of course phrases and sentences) can be said in different tones of voice, by varying the pitch, loudness, speed and timbre. These tones of voice cannot readily be analysed into segments, and they thus constitute a different field of phonology – non-segmental phonology (as opposed to the segmental phonology illustrated in Table 2.1). Non-segmental contrasts also need to be transcribed, and usually a system of accents or numbers is devised to indicate what is going on in the speech. For example, yès, with a grave accent, might be used to mark that the pitch of the voice is falling from high to low; yés, with an acute accent, might be used to mark a voice pitch rising from low to high. The contrast in meaning would be evident enough: yés is the tone you might use if you were puzzled; yès if you were giving a definite answer. There are, as we shall see, disorders of language which affect segmental phonology alone, non-segmental phonology alone, or both together.

Table 2.1. The phonemes of southern British English

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree