Approach to Differential Diagnosis

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

• INTRODUCTION

Whether it is called problem identification, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, or identifying potential drug-related problems, this universal process to identify patient problems is complex and multifaceted. Much effort and debate have gone into studying exactly how health professionals identify clinical problems (differential diagnosis) with limited success. Regardless of profession, the processes taught and used for identification of clinical problems are almost identical, with small differences in terminology, focus, and structure doing their best to disguise the commonalities among the processes. This chapter seeks to introduce the medical process of differential diagnosis for use by pharmacists in the self-care advisor and chronic disease management roles. It is effective and used by all health professionals who diagnose illness in humans, e.g., primarily physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. It is also the basis for communication among members of health care teams, envisioned as the future practice modality of choice by the Institute of Medicine. In addition, it will help pharmacists recognize the similarities between the medical process and the pharmacy problem identification processes, plus introduce some practical application of the medical process to the pharmacist’s assessment repertoire.

• ELEMENTS NEEDED TO ASSESS PATIENT ILLNESS

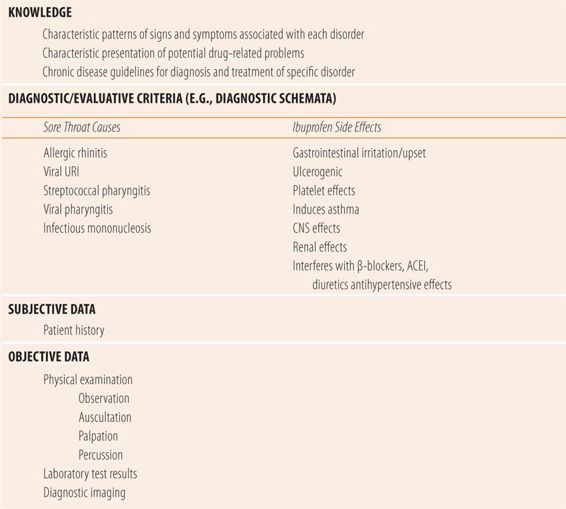

There are four major elements required to accurately assess patient illnesses and health problems (Table 1.1). The first is the knowledge of the characteristic patterns of signs and symptoms associated with each disorder, whether acute symptoms or illnesses, chronic diseases, or potential drug-related problems. The second is some type of evaluative or diagnostic criteria. For example, these can be a comprehensive list of all conditions that can cause sore throats or a shorter list that focuses on the most common conditions that cause a sore throat (diagnostic schemata). For chronic diseases and some acute diseases, those evaluative criteria could be national guidelines for the diagnosis/diagnostic workup of that disorder. The third and most important element is the patient history. The published medical literature supports the old adage, “with just the patient history, an accurate diagnosis can be made in 70-90% of patients. Physical examination just confirms the impression formed by the history.” What the adage and the literature really show is that the first three elements together yield an accurate diagnosis in 70% to 90% of adult patients who are capable of providing a history. Infants, children, unconscious, mechanically ventilated, or demented adults cannot provide an accurate history, so the adage does not apply to those situations. However, for pharmacists practicing in the self-care arena or disease management in an ambulatory setting, the adage and supporting literature are quite applicable. Therefore, the emphasis of this textbook is on the first three elements. The fourth element, data obtained from the physical examination, laboratory test results, and medical imaging (objective data), is also important. For those patients who are unable to provide an accurate history, objective parameters may be the only data available for accurate assessment. Regarding the fourth element, this textbook does not describe how to do a physical examination, how to conduct a laboratory test, or how to interpret a medical imaging procedure, but it does discuss interpretation of commonly used laboratory tests and how to integrate all objective findings into the assessment process, to improve the accuracy of the diagnosis.

| TABLE 1.1 | Elements Needed to Assess Patient Health Problems |

• ANALYTIC VERSUS NONANAYLTIC APPROACHES TO DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The analytic approach is very comprehensive, logical, stepwise in nature, and is used to look for all of the possible diagnoses

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree