By strict definition, antrectomy refers to removal of the gastrin-secreting portion of the stomach and when combined with a vagotomy results in an 85% reduction in gastric acid secretion.1,2 In the 1960s and 1970s, antrectomy with or without vagotomy was routinely performed for treatment of benign gastric and duodenal ulcers but, due to pharmacologic developments in reducing acid secretion and elucidation of the role of Helicobacter pylori in ulcer development, is now rarely performed for ulcer disease.3,4

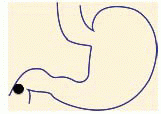

Today, the term antrectomy is loosely applied to any distal gastric resection and is indicated in recurrent or persistent gastric ulcers to rule out malignancy, complicated peptic ulcer disease (i.e., obstruction, hemorrhage, perforation), and for resection of certain neoplasms of the antrum and pyloric channel (Table 1).3

When an antrectomy is performed for complicated peptic ulcer disease, a vagotomy may be included to reduce the chance of anastomotic ulcer formation in patients who are not candidates for H. pylori treatment and lifelong proton pump inhibitor therapy due to unreliability, noncompliance, or medication side effects.5,6

Antrectomy is named by the type of gastrointestinal (GI) anastomosis performed.

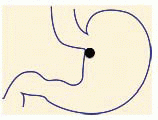

Billroth I procedure—antrectomy and gastroduodenostomy

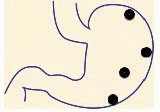

Billroth II procedure—antrectomy and gastrojejunostomy

A modification of the Billroth II procedure that involves a gastrojejunostomy via a Roux limb and is known as a Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy

Complicated peptic ulcer disease and distal gastric neoplasms, both benign and malignant, account for the vast majority of the antral resections performed today. These diagnoses will be discussed separately.

Peptic ulcer disease

Peptic ulcer disease refers to irritation of GI mucosa from gastric acid due to either increased acid presence or weakness in the mucosal protection and typically presents with epigastric pain.2,4 Peptic ulcers can occur anywhere in the GI tract, but duodenal and gastric ulcers are most common. Duodenal ulcers typically arise within 2 cm of the pylorus, are highly associated with H. pylori infection (>90%), and frequently resolve with appropriate H. pylori therapy. Gastric ulcers are less likely to be associated with H. pylori infection and are classified into five types based on their location and association with acid secretion (Table 2).7

The differential diagnosis of epigastric pain similar to that found in complicated peptic ulcer disease is chronic cholecystitis, acute pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis, functional indigestion or dyspepsia, gastritis, and reflux esophagitis. Complicated peptic ulcer disease can also present with upper GI hemorrhage, and a differential should include esophagitis (reflux and infectious); gastroesophageal varices, arteriovenous malformations; Mallory-Weiss tear; stress gastritis; and neoplasm of the esophagus, stomach, duodenum, pancreas, and biliary tree.

Lastly, pyloric obstruction due to chronic inflammation and scarring will cause nausea, emesis, and early satiety. The differential for these symptoms includes gastric motility disorders (i.e., gastroparesis), gastroenteritis, small bowel obstruction, electrolyte abnormalities, and extrinsic compression from pancreatic pseudocysts or neoplasms.

Distal gastric neoplasms—Gastric neoplasms include benign polyps, adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumors, lymphoma, B-cell mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas, GI stromal tumors, leiomyomas, and leiomyosarcomas. Any gastric neoplastic process can cause upper GI bleeding, epigastric pain, and luminal obstruction, and a differential similar to peptic ulcer disease should be considered.

Table 1: Indications for Antrectomy | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

All patients should undergo a thorough history and physical exam with questions focusing on the nature of the symptoms, specifically determining the relationship between symptoms and eating, deciphering whether symptoms are acute or chronic, and determining the severity of the symptoms. A vast majority of patients will have abdominal pain. Pain related to peptic ulcer disease that results from the corrosive effect of gastric acid on vulnerable GI mucosa and typically occurs in the epigastrium is described as gnawing or burning and follows a daily cycle. This pain typically arises shortly after eating breakfast and persists until lunch at which time the oral intake alleviates the pain. Relief is transient and pain recurs in the early afternoon and again persists until dinner. Meals, specifically ones consisting of milk and dairy products, and antacids provide temporary relief from ulcer pain. Acute, severe epigastric pain can signify ulcer perforation, whereas back pain suggests ulcer penetration into the pancreas.8

Nausea and vomiting can be seen with ulcer disease even in the absence of pyloric obstruction. Nausea that is chronic in nature and associated with early satiety and weight loss suggests inflammation and scarring of the pyloric channel due to chronic ulceration.

It is not uncommon for complicated peptic ulcers to present with upper GI bleeding, perforation, or obstruction in a patient with no history of peptic ulcer disease.

Bleeding—hematemesis, melena, recent diagnosis of anemia

Perforation—acute onset upper abdominal pain and peritonitis

Obstruction—nausea, emesis, food regurgitation, early satiety, weight loss

Acute or chronic upper GI bleeding can signify complicated ulcer disease and may present as melena, weakness, fatigue, general malaise, or a recent diagnosis of anemia.

Risk factors for developing ulcer disease include a history of H. pylori infection; smoking; Zollinger-Ellison syndrome; and use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), steroids, and other immunosuppressive medications.1,8 Therefore, an accurate medication list should be obtained and reviewed with the patient. History of previous ulcer disease should be elicited, and the success and timing of previous treatment modalities should be documented. Presence of H. pylori infection, completion of antibiotic therapy, and documentation of eradication is crucial (Table 3). Ulcers that persist despite appropriate

treatment of H. pylori, cessation of NSAID use, or are found in H. pylori-negative patients should raise suspicion for underlying malignancy.

A gastric lesion can also present with epigastric pain and obstruction. This pain is typically vaguer in nature and lacks a gnawing or burning component. Furthermore, these patients may describe a sensation of persistent fullness and early satiety despite hunger.

A subjective assessment of nutrition and functional status is necessary to evaluate the patient’s ability to tolerate a major surgical procedure.

Table 2: Peptic Ulcer Disease | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 3: Helicobacter pylori Testing | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree