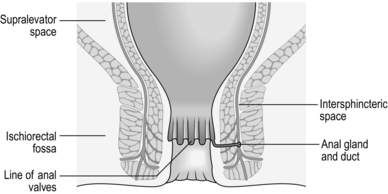

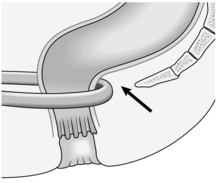

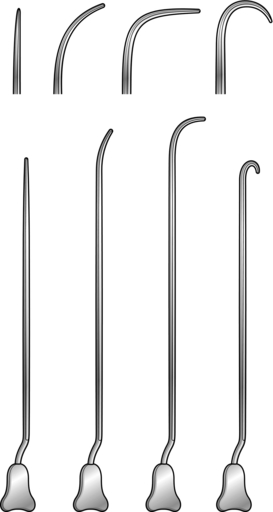

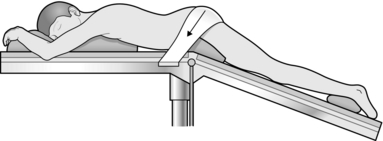

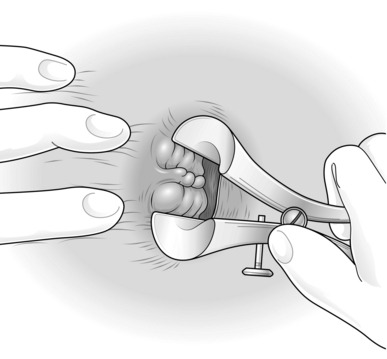

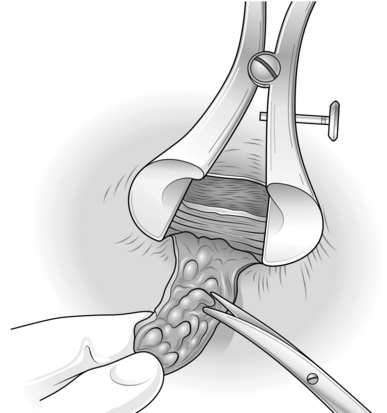

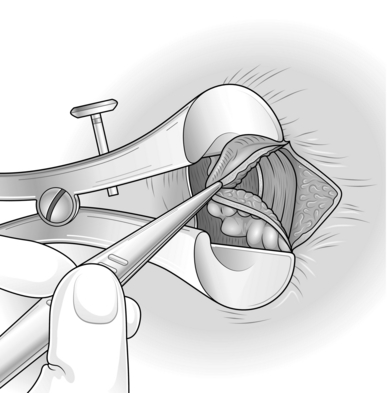

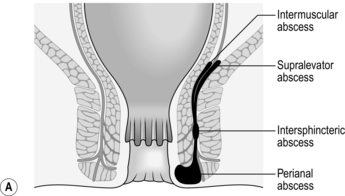

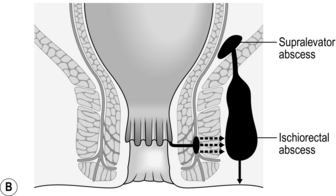

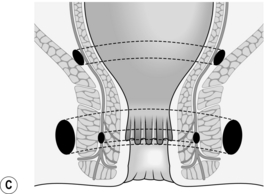

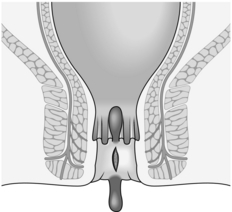

14 The anal canal extends from the anorectal junction to the anal margin and is approximately 3–4 cm long in men and 2–3 cm long in women. The lining epithelium is characterized by the anal valves midway along the anal canal. This line of the anal valves is often referred to as the ‘dentate line’ (Fig. 14.1): it does not represent the point of fusion between the embryonic hindgut and the proctoderm, which occurs at a higher level, between the anal valves and the anorectal junction. In this zone, sometimes called the transitional zone, there is a mixture of columnar and squamous epithelium. There are three important spaces around the anal canal: the intersphincteric space, the ischiorectal fossa and the supralevator space (Fig. 14.1). These spaces are important in the spread of sepsis and in certain operations: 1. Familiarize yourself with the small range of essential instruments for examination of the patient, such as the proctoscope and the rigid sigmoidoscope. In awake patients with anal sphincter spasm, use a small paediatric sigmoidoscope. 2. Operating proctoscopes of the Eisenhammer, Parks and Sims type are essential for operations on and within the anal canal. 3. Use a pair of fine scissors, fine forceps (toothed and non-toothed), a light needle-holder, Emett’s forceps and a small no. 15 scalpel blade for intra-anal work. Alternatively, diathermy dissection creates a virtually bloodless field. 4. For fistula surgery have a set of Lockhart-Mummery fistula probes (Fig. 14.3), together with a set of Anel’s lacrimal probes. 5. Most patients require no preparation, or two glycerine suppositories, to ensure that the rectum is empty before anal surgery. If for any reason the bowels need to be confined postoperatively, carry out a full bowel preparation to empty the whole large intestine. 6. Minor operations can be performed under local infiltration anaesthesia; larger procedures demand regional or general anaesthesia. 7. For outpatient procedures use the left lateral position, or alternatively the knee-elbow position. For anal operations most British surgeons favour the lithotomy position, although the prone jack-knife position (Fig. 14.4) can also be used. 8. If you prefer to shave the area before starting an anal operation, carry it out in the operating theatre immediately beforehand, where there is good illumination. 1. Haemorrhoids usually do not need treatment if the symptoms are minimal and you have excluded a primary cause. 2. Small internal haemorrhoids can be treated by injection sclerotherapy. Prolapsing haemorrhoids may be ligated with rubber-bands. Large prolapsing haemorrhoids, which are usually accompanied by a significant external component, are best treated by haemorrhoidectomy. The advent of day-case diathermy haemorrhoidectomy has rendered surgical treatment simpler and more available than in the past. 3. As a rule avoid treating haemorrhoids if the patient also has Crohn’s disease. 1. Pass the full-length proctoscope and withdraw it slowly to identify the anorectal junction – the area where the anal canal begins to close around the instrument. 2. Place a ball of cotton wool into the lower rectum with Emett’s forceps to keep the walls apart. Since you will not usually remove it, warn the patient that it will pass out with the next motion. 3. Identify the position of the right anterior, left lateral and right posterior haemorrhoids. 4. Fill a 10-ml Gabriel pattern syringe with 5% phenol in arachis oil with 0.5% menthol (oily phenol BP). 5. Through the full-length proctoscope, insert the needle into the submucosa at the anorectal junction at the identified positions of the haemorrhoids in turn. Inject 3–5 ml of 5%phenol in arachis oil into the submucosa at each site, to produce a swelling with a pearly appearance of the mucosa in which the vessels are clearly seen. Move the needle slightly during injection to avoid giving an intravascular injection. 6. Delay removing the needle for a few seconds following the injection, to lessen the escape of the solution. If necessary, press on the injection site with cotton wool to minimize leakage. 7. Warn the patient to avoid attempts at defecation for 24 hours. 1. This can also be performed as an outpatient procedure and does not require anaesthesia. 2. There are several different designs of band applicator (Fig. 14.5); the suction bander is relatively expensive, but is convenient and easy to use. 3. There are two conceptually different strategies: 4. Enquire about anticoagulants pre-procedure. Banding should not be performed if the patient is on Warfarin or Clopidigrel and some surgeons prefer to stop Aspirin as well. NOTE: the bands are usually marked as being latex-free. 1. Load one band onto the end of the sucker and one onto the applicator before applying your gloves. 2. Pass the full-length proctoscope and withdraw it slowly to identify the anorectal junction. Position the end of the proctoscope midway between the anorectal junction and the dentate line. 3. The haemorrhoids will fall into view and then the end of the suction device can be applied. Cover the hole on the device to activate the suction and then wait for a few seconds. 4. The band can then be deployed. 5. Any number of haemorrhoids can be banded on each occasion; however, the view is often obscured once two bands have been applied. Repeat banding where necessary but delay it for 6–8 weeks. 1. Advise the patient to take a mild analgesic and sit in a hot bath if the procedure causes discomfort. 2. Pain developing slowly in 1–2 days may be from ischaemia. Analgesics relieve the pain. Give metronidazole tablets 200–400 mg three times daily, which may help reduce inflammation. 3. Advise the patient that the haemorrhoid and the band should drop off after 5–10 days and may be accompanied by a small amount of bleeding. 4. Warn the patient that secondary haemorrhage occurs in approximately 2% any time up to 3 weeks after the application. Tell the patient to report to hospital if this is severe, since it may require transfusion and operative control of the bleeding. 1. Start lactulose, a non-absorbed disaccharide which produces an osmotic bowel action, 30 ml twice daily 2 days preoperatively. This reduces postoperative pain. 2. Give oral metronidazole 400 mg t.d.s. for 5 days, which also significantly reduces postoperative pain. 3. Place the anaesthetized patient in the lithotomy position with some head-down tilt. Avoid caudal anaesthetic as it may provoke retention of urine. 1. Plan the operation by inserting the Eisenhammer retractor and establish which haemorrhoids need to be removed; also estimate the state and size of the skin bridges (Fig. 14.6). 3. If there is one additional haemorrhoid you may: 4. The haemorrhoids may be even more extensive and may be circumferential. In this case: 1. Inject bupivacaine (Marcaine) 0.25% with adrenaline (epinephrine) 1:200 000 into each skin bridge and into the external component of each haemorrhoid to be excised. 2. Wait, and gently massage away excess fluid from the injection with a moistened gauze. 3. Commence with the left lateral haemorrhoid. Place the Eisenhammer retractor in the anal canal and open it sufficiently to put the internal sphincter under tension. This demonstrates the plane of the dissection (Fig. 14.8). 4. Grasp the external component and excise it with electrocautery, using cutting diathermy on skin and coagulating diathermy for all other dissection (Fig. 14.9). 5. Now extend the haemorrhoidal dissection up the anal canal, separating the haemorrhoid from the underlying internal sphincter. 6. Narrow the pedicle as you dissect up towards the apex, otherwise you risk encroaching on the skin bridge. 7. When you have encompassed the internal component of the haemorrhoid, simply transect the pedicle with diathermy. 8. Repeat the procedure on the right anterior haemorrhoid and then the right posterior haemorrhoid. 9. Ensure complete haemostasis and check each wound and apex. 1. Allow the patient home after recovery from the anaesthetic. 2. Warn that there is likely to be an early increase in pain 3–5 days postoperatively. 3. Pain can usually be satisfactorily controlled with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). 4. Manage the bowels with lactulose 30 ml orally twice daily until defecation is comfortable. 5. Some surgeons advocate a reversible chemical sphincterotomy with locally applied 0.2% glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) applied three times daily. 6. Review the patient in the outpatient clinic within 10–12 days. 1. Most ulcers at the anal margin are simple fissures in ano, possibly associated with a sentinel skin tag and/or hypertrophied anal papilla or anal polyp. 2. Exclude excoriation in association with pruritus ani, Crohn’s disease, primary chancre of syphilis, herpes simplex, leukaemia and tumours. 3. Treat superficial fissures with 2% diltiazem ointment (Anoheal™) or 0.4% glyceryl trinitrate cream (Rectogesic™) twice a day. GTN can cause headaches; diltiazem occasionally causes local irritation. 4. Botulinum toxin injection is an alternative therapy, especially useful in patients who are non-compliant in regularly applying creams. Doses of botulinum toxin type A (Botox) may range from 2.5 to 50 units and reports have included injections into the internal and external anal sphincter either directly into the fissure or at sites removed from it. Dysport is an alternative preparation which requires roughly three times the number of units used with Botox. However, studies suggest that the two formulations are not bioequivalent, whatever the dose relationship. 5. Reserve operation for failures, which are more common when there is a sentinel tag, an anal polyp, exposure of the internal sphincter or undermining of the edges (Fig. 14.11). Fig. 14.11 A fissure with a sentinel skin tag, an anal polyp and undermining of the edges of the ulcer. 6. Anal dilatation is no longer an acceptable treatment as it causes unpredictable stretching of the internal and external sphincters and lower rectum, producing an unacceptable risk of incontinence. 7. The standard procedure is a lateral (partial internal) sphincterotomy. 1. This is very successful, curing more than 95% of patients. It was introduced by Eisenhammer in 1951. 2. To avoid exacerbating the pain, avoid preoperative preparation. 3. The operation can be carried out as a ‘day-case’ procedure. 4. Warn the patient of a 1 in 20 chance of permanent flatus incontinence and a 1 in 200 chance of faecal leakage. 1. Place the patient in the lithotomy position, with general or regional anaesthesia. 2. Pass an Eisenhammer bivalve operating proctoscope. Examine the fissure to exclude induration suggestive of an underlying intersphincteric abscess. 3. Remove hypertrophied anal papillae or a fibrous anal polyp, sending them for histopathological examination. Remove a sentinel skin tag. 4. Rotate the operating proctoscope to demonstrate the left lateral aspect of the anal canal. Palpate the lower border of the internal sphincter muscle. If desired, you may replace the Eisenhammer retractor with a Parks’ retractor which permits outward traction, making the internal sphincter more obvious. 5. Make a small incision 1 cm long in line with the lower border of the internal sphincter. Insert scissors into the submucosa, gently separating the epithelial lining of the anal canal from the internal sphincter, and also into the intersphincteric space to separate the internal and external sphincters. 6. If you make a hole in the mucosa open it completely to avoid the risk of sepsis. 7. Clamp the isolated area of the internal sphincter with artery forceps for 30 seconds. This markedly reduces haemorrhage. 8. With one blade of the scissors on each side of it, divide the internal sphincter muscle up to the level of the top of the fissure (Fig. 14.12). 1. Most abscesses and fistulas in the anal region arise from a primary infection in the anal intersphincteric glands. Furthermore, they represent different phases of the same disease process. An acute-phase abscess develops when free drainage of pus is prevented by closure of either the internal or external opening of the fistula (or both). 2. Other causes of sepsis in the perianal region include pilonidal infection, hidradenitis suppurativa, Crohn’s disease, tuberculosis and intrapelvic sepsis draining downwards across the levator ani. 3. Once established, an intersphincteric abscess may spread vertically downwards to form a perianal abscess or upwards to form either an intermuscular abscess or supralevator abscess, depending upon which side of the longitudinal muscle spread occurs (Fig. 14.13A). Horizontal spread medially across the internal sphincter may result in drainage into the anal canal, but spread laterally across the external sphincter may produce an ischiorectal abscess (Fig. 14.13B). Finally, circumferential spread of infection may occur from one intersphincteric space to the other, from one ischiorectal fossa to the other and from one supralevator space to the other (Fig. 14.13C). 4. Once an abscess has formed surgical drainage must be instituted; antibiotics have no part to play in the primary management. As the tissues are inflamed and oedematous, do the minimum to promote resolution of the infection. More tissue can be divided later to resolve the condition. Send a specimen of pus to the laboratory for culture. The presence of intestinal organisms suggests the presence of a fistula. 5. Avoid preoperative preparation of the bowel as it causes unnecessary pain. 6. Place the anaesthetized patient in the lithotomy position and shave the operation area.

Anorectum

ANATOMY

Spaces

The intersphincteric space lies between the two sphincters and contains the terminal fibres of the longitudinal muscle of the large intestine. It also contains the anal intermuscular glands, approximately 12 in number, arranged around the anal canal. The ducts of these glands pass through the internal sphincter and open into the anal crypts.

The intersphincteric space lies between the two sphincters and contains the terminal fibres of the longitudinal muscle of the large intestine. It also contains the anal intermuscular glands, approximately 12 in number, arranged around the anal canal. The ducts of these glands pass through the internal sphincter and open into the anal crypts.

The ischiorectal fossa lies lateral to the external sphincter and contains fat. Abscesses may occur in this site as the result of horizontal spread of infection across the external sphincter.

The ischiorectal fossa lies lateral to the external sphincter and contains fat. Abscesses may occur in this site as the result of horizontal spread of infection across the external sphincter.

The supralevator space lies between the levator ani and the rectum. It is also important in the spread of infection.

The supralevator space lies between the levator ani and the rectum. It is also important in the spread of infection.

Prepare

HAEMORRHOIDS

Appraise

INJECTION SCLEROTHERAPY

Action

RUBBER-BAND LIGATION

Band, or inject, above the haemorrhoid in order to ‘hitch’ it back into its normal place. Grasp the redundant mucosa proximal to the haemorrhoid and band that.

Band, or inject, above the haemorrhoid in order to ‘hitch’ it back into its normal place. Grasp the redundant mucosa proximal to the haemorrhoid and band that.

Action

Aftercare

HAEMORRHOIDECTOMY

Prepare

Assess

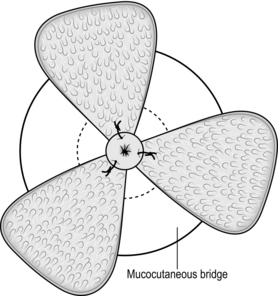

A three-quadrant haemorrhoidectomy will be sufficient

A three-quadrant haemorrhoidectomy will be sufficient

There is one additional haemorrhoid that needs removal, or the situation is more complex than this.

There is one additional haemorrhoid that needs removal, or the situation is more complex than this.

Leave it and be prepared to return on another occasion if it proves troublesome

Leave it and be prepared to return on another occasion if it proves troublesome

Fillet it out by undermining the skin bridge

Fillet it out by undermining the skin bridge

Another technique is to divide the skin bridge above the dentate line, reflect it out of the anus, and trim the haemorrhoid with the back of a pair of scissors. Now excise any redundant mucosa and stitch the trimmed flap back into position with 2/0 synthetic absorbable sutures of Vicryl (Fig. 14.7).

Another technique is to divide the skin bridge above the dentate line, reflect it out of the anus, and trim the haemorrhoid with the back of a pair of scissors. Now excise any redundant mucosa and stitch the trimmed flap back into position with 2/0 synthetic absorbable sutures of Vicryl (Fig. 14.7).

Perform a standard three-quadrant haemorrhoidectomy and return on another occasion to deal with any residual haemorrhoids

Perform a standard three-quadrant haemorrhoidectomy and return on another occasion to deal with any residual haemorrhoids

If you are experienced in the technique, consider performing the circumferential Whitehead haemorrhoidectomy described in 1882 by the English surgeon Walter Whitehead (1840–1914). He described the excision of a tubular segment of the anal canal, with mucosal-cutaneous re-anastomosis. Use polyglactin 910 (Vicryl). Difficulties include the Whitehead deformity – mucosal ectropion (Greek: ek = out + trepein = to turn) – and late stenosis.

If you are experienced in the technique, consider performing the circumferential Whitehead haemorrhoidectomy described in 1882 by the English surgeon Walter Whitehead (1840–1914). He described the excision of a tubular segment of the anal canal, with mucosal-cutaneous re-anastomosis. Use polyglactin 910 (Vicryl). Difficulties include the Whitehead deformity – mucosal ectropion (Greek: ek = out + trepein = to turn) – and late stenosis.

Action

Aftercare

FISSURE

Appraise

LATERAL SPHINCTEROTOMY

Appraise

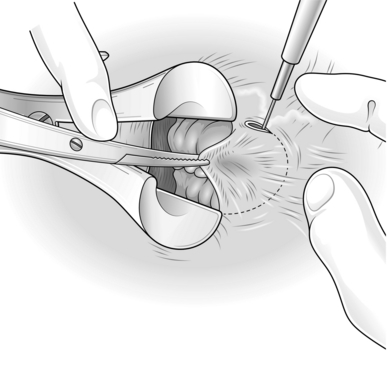

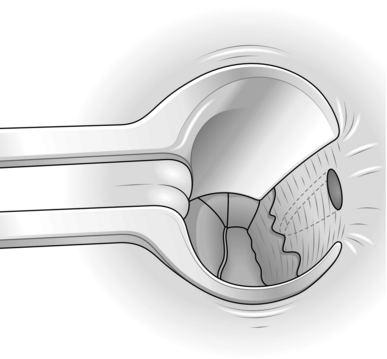

Action

ANAL ABSCESS AND FISTULA

Appraise

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Anorectum