Anatomy of the Breast

Kirby I. Bland

Breast tissue is embryologically derived and anatomically matures as a modified sweat gland. Mammary tissues represent a unique feature of the mammalian species. Embryologically, the paired mammary glands congruently develop within the “milk line,” which extends between the limb buds from the primordial axilla distally to the inguinal area. The number of paired glands varies widely among the various mammalian species, but in humans and most primates, only one pair of glands normally develops in the pectoral region, one gland on each side. In approximately 1% of the female population, supernumerary breasts (polymastia) or nipples (polythelia) may develop. Supernumerary appendages principally develop along the milk lines. While there is normally minimal additional development of the mammary gland during postnatal life in the male, in the female extensive growth and development are evident. Evident postnatal development of the female mammary gland is related to age and is primarily regulated by hormones (estrogens) that influence reproductive function. The greatest development of the breast is attained by the age of 20 years, and atrophy begins premenopausally at approximately the age of 40 years. During pregnancy and lactation, striking variants occur in both the amount (volume) of glandular tissue and the functional activity of the breast. Structural changes are also observed during menstrual cycles that result from variations in ovarian hormone levels. During menopause, with the changes occurring in the hormonal secretory activity of ovarian function, the mammary gland undergoes involution and is replaced by fat and connective tissue, and thereafter, diminishes its structural volume, form, and contour.

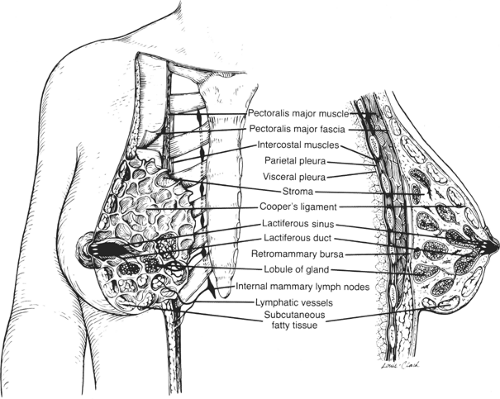

The glands of the breast are located within the superficial fascial compartment of the anterior chest wall. This organ consists of 15 to 20 lobes of tubuloalveolar glandular tissue, fibrous connective tissue that supports its lobes, and the adipose tissue that resides in parenchyma between the lobes. Subcutaneous connective tissue typically does not possess a distinctive capsule around breast components; rather, this tissue surrounds the gland and extends as septa between the lobes and lobules, providing longitudinal and gravitational support to the glandular elements. The deep layers of the superficial fascia that lie upon the posterior surface of the breast fuse with the deep (pectoral) fascia of the chest wall. A distinct space, the retromammary bursa, can be identified anatomically on the posterior aspect of the breast and resides between the deep layer of the superficial fascia and the deep investing fascia of the pectoralis major and the contiguous muscles of the thoracic wall (Fig. 1). The retromammary bursa contributes to the mobility of the breast on the chest wall. Fibrous thickenings of supportive connective tissue interdigitate between the parenchymal tissue of the breast and extend from the deep layer of the superficial fascia to attach to the dermis of the skin. These fibrous suspensory structures, known as Cooper ligaments, located perpendicular to the delicate superficial fascial layers of the dermis, allow remarkable mobility of the gland while providing structural support and breast contour.

The fully mature female breast extends from the level of the second or third rib inferiorly to the inframammary fold that is located at the level of the sixth or seventh rib. Laterally, the breast extends from the lateral border of the sternum to the anterior or midaxillary line. Breast parenchyma extends commonly into the anterior axillary fold as the axillary tail of Spence. The upper half of the breast, particularly the upper outer quadrant, contains the greater volume of glandular tissue than the remainder of the breast. The posterior or deep surfaces of the breast rest upon portions of the fasciae of the pectoralis major, serratus anterior, and external oblique muscles; the gland also resides on upper portions of the anterior rectus sheath.

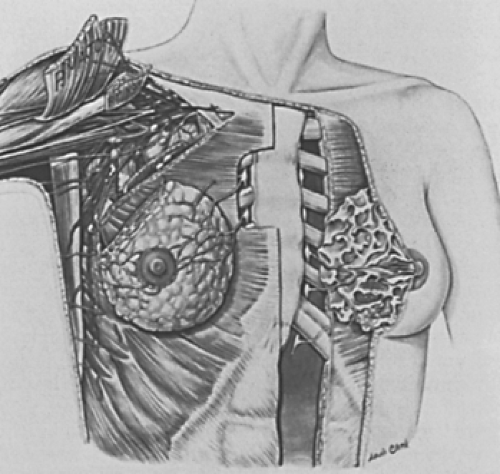

The anatomical boundaries of the axilla represent a pyramidal compartment located between the upper extremity and the thoracic wall; this structure has four boundaries inclusive of a base and an apex (Fig. 2). The curved oblong base consists of axillary fascia. The apex of the axilla represents an aperture that extends into the posterior triangle of the neck via the cervicoaxillary canal. Most structures that course between the neck and the upper extremity enter this anatomic passage, which is bounded anteriorly by the clavicle, medially by the first rib, and posteriorly by the scapula. The anterior wall of the axilla is composed of the pectoralis major and minor muscles and their associated fasciae. The posterior wall is formed primarily of the subscapularis muscle, located on the anterior surface of the scapula, and to a lesser extent by the teres major and latissimus dorsi muscles. The lateral wall of the axilla is the bicipital groove, a thin strip of condensed muscular tissue between the insertion of the musculature of the anterior and posterior compartments. The medial wall is composed of the serratus anterior muscle.

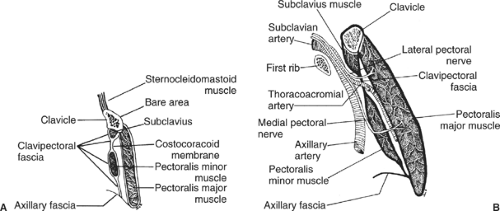

The fascia of the pectoralis major and minor muscles are evident in two distinct planes: The superficial layer, called the pectoral fascia, invests the pectoralis major muscle, whereas the deep layer, called the clavipectoral or costocoracoid fascia, extends from the clavicle to the axillary fascia in the floor of the axilla and encloses the subclavius and the pectoralis minor muscle (Fig. 3).

The costocoracoid membrane represents the upper portion of the clavipectoral fascia and is pierced by the cephalic vein, the lateral pectoral nerve, and branches of the thoracoacromial trunk. The medial pectoral nerve does not penetrate the costocoracoid membrane, but enters the deep surface of the pectoralis minor and passes through the anterior investing fascia of the pectoralis minor to innervate the pectoralis major muscle. Caudad portions of the clavipectoral fascia, which are anatomically inferior to the pectoralis minor, are sometimes referred to as the suspensory ligament of the axilla or the coracoaxillary fascia. Many surgeons refer to this anatomic landmark as Halsted’s ligament, which represents a dense condensation of the clavipectoral fascia that extends from the medial aspect of the clavicle, attaches to the first rib, and invests the subclavian artery and vein as each traverse the first rib.

Within the axilla are the great vessels and nerves of the upper extremity, which, together with the other axillary contents, are encircled by loose connective tissue. These vessels and nerves are anatomically contiguous and are enclosed within an investing layer of fascia referred to as the axillary

sheath. The axillary artery can be divided into three anatomical segments within the axilla proper:

sheath. The axillary artery can be divided into three anatomical segments within the axilla proper:

Located medial to the pectoralis minor muscle, the first segment gives rise to one branch, the supreme thoracic, which supplies the upper thoracic wall inclusive of the first and second intercostal spaces.

The second segment of this artery, located immediately posterior to the pectoralis minor, gives rise to two branches, the thoracoacromial trunk and the lateral thoracic artery. Pectoral branches of the thoracoacromial and lateral thoracic arteries supply the pectoralis major and minor muscles. Identification of these vessels during surgical dissection of the axilla is imperative to provide safe conduct of the procedure. The lateral thoracic artery gives origin to the lateral mammary branches.

The third segment of this vessel, located lateral to the pectoralis minor muscle, gives rise to three branches. These include the anterior and posterior humeral circumflex arteries that supply the upper arm, and the subscapular artery, which is the largest branch within the axilla. After a short course, the subscapular artery gives origin to its terminal branches, the subscapular circumflex and the thoracodorsal arteries. The thoracodorsal artery, which courses with its corresponding nerve and vein, crosses the subscapularis muscle, providing its substantial blood supply, as well as that of the serratus anterior and latissimus dorsi muscles.

Tributaries of the axillary vein follow the course of the branches of the axillary artery, usually in the form of venae comitantes, paired veins that follow the course of the artery. The cephalic vein passes in the groove between the deltoid and pectoralis major muscles, and thereafter enters the axillary vein after piercing the clavipectoral fascia.

Anatomically, the axillary artery is contiguous with various portions of the brachial plexus throughout its course in the axilla. The cords of the brachial plexus are named according to their structural and positional relationship with the axillary artery—medial, lateral, and posterior—rather than their anatomic position in the axilla or on the chest wall.

These are three nerves of principal interest to surgeons that are located in the axilla. The long thoracic nerve, located on the medial wall of the axilla, arises in the neck from the fifth, sixth, and seventh cervical roots (C5, C6, and C7) with entry in the axilla via the cervicoaxillary canal. This medially placed nerve lies on the lateralmost surface of the serratus anterior muscle and is invested by the serratus fascia such that it might be accidentally divided together with resection of the fascia during surgical dissection (sampling) of lymphatics of the axilla. The long thoracic nerve, although diminutive in size, courses a considerable anatomic distance to supply the serratus anterior muscle; injury or division of this nerve results in the “winged scapula” deformity with denervation of the muscle group and the inability to provide shoulder fixation. The thoracodorsal nerve takes origin from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus and innervates the laterally placed latissimus dorsi muscle. Injury or division is inconsequential to primary shoulder function; however, preservation of this nerve is essential to provide transfer survival and motor function preservation for the myocutaneous flap used for the latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous reconstruction. The intercostobrachial nerve is formed by the merging of the lateral cutaneous branch of the second intercostal nerve with the medial cutaneous nerve of the arm; this nerve provides sensory innervation of the skin of the apex and lateral axilla and the upper medial and inner aspect of the arm. A second intercostobrachial nerve may sometimes form an anterior branch of the third lateral cutaneous nerve.

Blood Supply of the Breast

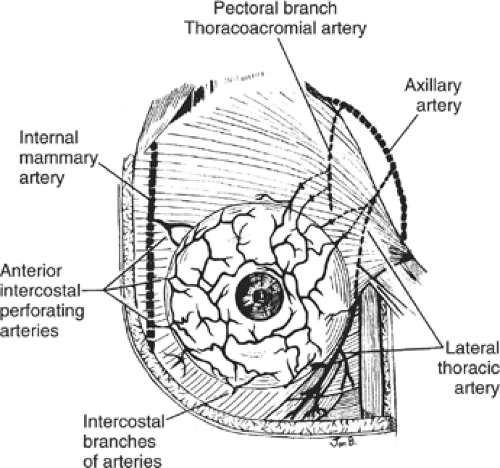

Blood supply to the mammary gland is derived from perforating branches of the internal mammary artery, lateral branches of the posterior intercostal arteries, and several branches of the axillary artery. The latter vessels include the highest thoracic, lateral thoracic, and pectoral branches of the thoracoacromial artery (Figs. 4 and 5). Branches from the second, third, and fourth anterior perforating arteries pass to the breast as medial mammary arteries.

The lateral thoracic artery branches allow perfusion to the serratus anterior muscle, both the pectoralis muscles, and the subscapularis muscle, and also supply the axillary lymphatics and supporting fatty tissues. The posterior intercostal arteries give rise to mammary branches in the second, third, and fourth intercostal spaces.

Although the thoracodorsal branch of the subscapular artery does not contribute to the primary blood supply of the breast per se, this vessel is intimately associated with the central and scapular lymph node groups of the axilla. This fact should be taken into consideration during axillary node dissection, as bleeding that is difficult to control can result when penetrating branches of this vessel are severed.

Principal venous outflow of the gland has preferential directional flow toward the axilla, with the veins principally paralleling the path of the arterial distribution. The superficial venous plexus of mammary parenchyma has extensive anastomoses that may be evident through the overlying skin. Circumscribing the nipple, superficial veins form an anastomotic circle, the circulus venosus. Veins from this circle and from deeper aspects of the gland converge to drain blood to the periphery of the breast, and thereafter into vessels that terminate in the internal mammary, axillary, and internal jugular veins.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree