Anaplastic Large-Cell Lymphoma

Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL) was originally designated as Ki-1 lymphoma by Stein and colleagues in 1985 (1). The name was based on the constant and uniform positivity of the neoplastic cells with the Ki-1 antibody, subsequently shown to be specific for CD30. In the original description, it was recognized that Ki-1 lymphoma was heterogeneous and, in retrospect, the initial study included cases of CD30+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and possibly cases of syncytial variant nodular sclerosis Hodgkin lymphoma (1). Over the years, our understanding of ALCL has evolved substantially. The t(2;5)(p23;q35) was initially identified in a subset of neoplasms originally designated as malignant histiocytosis (2,3). Subsequently, it was realized that a subset of these lesions were CD30+. The genes involved in the t(2;5) were cloned and shown to be anaplastic lymphoma kinase (alk) at 2p23 and nucleophosmin (npm) at 5q35 (4). The development of anti-ALK antibodies followed. In aggregate, these advances and other studies led to the recognition that ALCL is a neoplasm of T- or null-cell lineage. Cases of CD30+ DLBCL and classical Hodgkin lymphoma were excluded from this entity, and the distinctive features of ALCL arising in the skin were also recognized.

In 2001, the World Health Organization (WHO) classification summarized the state of the field. The diagnosis of ALCL includes two subsets of neoplasms that either express or do not express ALK protein (5). Depending on the percentage of pediatric versus adult patients, as well as other factors, 60% to 85% of all cases of ALCL are ALK+. Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma arising in the skin, virtually always ALK-, is now designated as a unique entity, cutaneous ALCL, and excluded from the category of ALCL in the WHO classification (5). Although the WHO classification of ALCL is helpful, the field is not static and our understanding of ALCL and its mimics has continued to expand. As was suggested in the WHO classification, a general consensus has emerged that ALK+ and ALK– ALCL are separate entities (6). Many pathologists now believe that the term ALK– ALCL should not be used, as these neoplasms are not unique at the molecular level; they prefer classifying these neoplasms as peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified (PTCL-U). Others believe that the distinctive histologic features of these neoplasms and the better prognosis shown in one study (discussed later) still justify using the term ALK– ALCL.

For these reasons, it is no longer adequate to establish the diagnosis of ALCL without including ALK status in the diagnostic line of the surgical pathology report, and we discuss ALK+ and ALK– ALCL separately in this chapter.

Alk+ Anaplastic Large-Cell Lymphoma

Definition

ALK+ ALCL is a lymphoma of T- or null-cell lineage characterized by expression of ALK (CD246) as a result of molecular abnormalities involving alk at chromosome 2p23 (5,6). In the most common histologic variant, the neoplastic cells are uniformly large with abundant cytoplasm and pleomorphic, sometimes horseshoe-shaped nuclei. A subset of these neoplastic cells have the cytologic features of so-called hallmark cells (discussed later). The neoplastic cells often exhibit a sinusoidal growth pattern. CD30 is expressed in a distinctive membranous and paranuclear (target-like) pattern by the large neoplastic cells of ALK+ ALCL. Patients with ALK+ ALCL have a substantially better overall survival than patients with ALK– ALCL (7).

Synonyms

Ki-1 lymphoma; Ki-1+ large-cell anaplastic lymphoma (Kiel); diffuse large-cell or large-cell immunoblastic (Working Formulation); systemic ALCL; malignant histiocytosis (subset).

Epidemiology

In most epidemiologic studies, ALK+ and ALK– ALCL are not separated. In the United States, for the interval 1992–2001, ALCL represented 0.8% of all lymphomas (including both Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas) and 13.9% of all T/NK-cell lymphomas in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database (8). The overall incidence for ALCL was 0.25 per 100,000 person-years, but this was higher in whites and African-Americans, 0.34 and 0.38 respectively, than in Asian-Americans, 0.17. The male-to-female ratio was 1.9 in whites and 2.0 in African-Americans, but only 1.3 in Asian-Americans (8). According to the WHO classification, ALCL represents approximately 3% of adult and 10% to 30% of all childhood non-Hodgkin lymphomas (5). In general, these numbers refer to patients in North America and western Europe. In Asia, the overall incidence and relative frequency of ALCL are lower.

Pathogenesis

ALK+ ALCL is characterized by molecular abnormalities involving alk, located at chromosome 2p23 (5). All of these lesions lead to overexpression of ALK. Nine different abnormalities involving alk have been reported to date, eight translocations and one inversion, with additional rare molecular alterations likely to be discovered in the future (Table 75.1) (6,9). Of these, the t(2;5)(p23;q35) is most common, detected in approximately 75% to 80% of cases of ALK+ ALCL. As a result of this translocation, nucleophosmin (npm) and alk are disrupted and recombined to form a novel npm-alk fusion gene composed of the 5′ end of npm and the 3′ end of alk. This encodes for a novel protein, NPM-ALK, composed of the amino-terminal portion of NPM and the carboxy-terminal portion of ALK (7,9). The amino-terminal portion of NPM has a strong promoter that drives NPM-ALK overexpression. This portion of NPM also

has an oligodimerization domain that allows NPM-ALK proteins to form dimers and multimers. This simulates normal ligand binding, leading to constitutive activation of ALK, which occurs via autophosphorylation of numerous tyrosine residues within the catalytic domain of the protein.

has an oligodimerization domain that allows NPM-ALK proteins to form dimers and multimers. This simulates normal ligand binding, leading to constitutive activation of ALK, which occurs via autophosphorylation of numerous tyrosine residues within the catalytic domain of the protein.

TABLE 75.1 ALK FUSION PROTEINS IN ALCL | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

NPM is a ubiquitously expressed protein that has many normal cellular functions, including being involved in ribosomal assembly, centrosomal duplication, p53 regulation, and nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of proteins (10). ALK is a receptor tyrosine kinase and a member of the insulin receptor superfamily. Full-length ALK has an extracellular region that binds to ligand, a small transmembrane segment, and an intracellular, cytoplasmic portion that contains the catalytic domain of ALK. ALK is normally expressed in a highly restricted manner, being present only in a subset of cells in the nervous system (9). ALK is not normally expressed by lymphocytes and thus overexpression in lymphocytes is abnormal and evidence of lymphoma. The normal function of ALK is unknown. Pleiotrophin and midkine have been suggested as possible ligands of ALK, but these ligands do not intuitively have a role in lymphocyte biology, and it seems likely that other ligands may exist.

NPM-ALK, as well as ALK activation via other molecular abnormalities, is oncogenic in vitro and in vivo (11,12). Furthermore, ALK+ ALCL appears to be dependent on ALK activation, as inhibition of ALK inhibits tumor growth (13). ALK activation then leads to the activation of many cellular pathways including phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K)/AKT, phospholipase γ C, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), RAS, and others resulting in neoplastic transformation (10). It is important to remember that alk abnormalities alone are essential, but are probably not sufficient to induce lymphoma; other abnormalities are most likely also required.

In other, less common molecular abnormalities involving alk, the translocation partner also plays an essential role by allowing ALK to form dimers and multimers. Most of these partner genes also have oligodimerization domains. However, there are exceptions to the rule. For example, moesin, involved in the t(2;X), does not have an oligodimerization domain, but moesin is normally tethered to the plasma cell membrane, thereby allowing ALK molecules to come into contact with each other in this manner. Although the cellular mechanisms that result in neoplastic transformation are likely to be slightly different for each translocation involving alk, overexpression of ALK is the most important event biologically. Clinically, patients with ALK+ ALCL have a similar prognosis, regardless of the type of abnormality involving alk (14).

CD30 is uniformly and strongly expressed by ALCL (both ALK+ and ALK-). CD30 is a transmembrane receptor that is a member of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily. Binding of CD30 ligand with CD30 elicits many cellular responses. A study using ALCL cell lines showed that CD30 stimulation triggered two competing effects: caspase activation and NFκB-mediated survival (14a).

Clinical Findings

The age range of patients with ALK+ ALCL is very broad. In a large study of 123 cases of ALK+ ALCL, patient age ranged from 3 months to 92 years, with a mean of 21.3 years (15). Patients with ALK+ ALCL can present with localized or advanced-stage disease, but approximately 75% have advanced disease. Systemic, B-type symptoms are common, particularly high fever. The serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and β-2-microglobulin levels are often elevated. Many patients have an intermediate or high International Prognostic Index score. The clinical pace of disease can be very rapid.

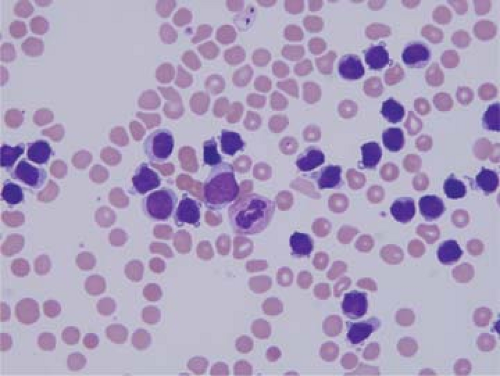

Lymph nodes are the most common sites of involvement by ALK+ ALCL, but involvement of extranodal sites is common. The most common extranodal sites are skin, soft tissue, bones, and lung, each occurring in approximately 10% to 20% of patients (2,7,16). Bone marrow involvement occurs in 10% to 30% of patients, depending in part on the method of analysis; routine histologic analysis is less sensitive than immunohistochemical staining as the latter can detect very small numbers of CD30+ or ALK+ neoplastic cells (17). ALK+ ALCL can become leukemic, with very high leukocyte counts. This is very rare at time of initial diagnosis and relatively more common at relapse. Leukemic involvement is most often associated with the small-cell or lymphohistiocytic variants (Fig. 75.1) (18). The brain, gastrointestinal tract, and mediastinum are rarely involved in ALK+ ALCL, in less than 5% of cases (6,19).

Histologic Findings

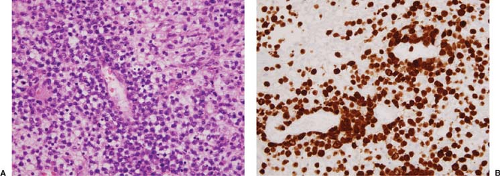

ALK+ ALCL can partially or completely replace lymph node architecture (2,5,6,7). In partially involved lymph nodes, representing 40% to 50% of specimens, the neoplasm preferentially involves and distends sinuses (Fig. 75.2); is limited to the paracortex, or both; and spares lymphoid follicles (Fig. 75.3) (5,6). Cases with minimal sinusoidal involvement can be missed or can misinterpreted as a metastatic neoplasm involving the lymph node. Prominent involvement of sinuses also historically led to the old term malignant histiocytosis being used for

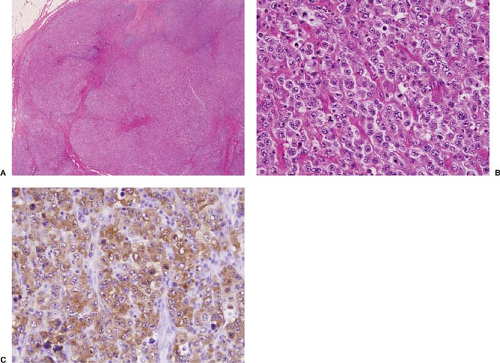

these neoplasms. In approximately 50% to 60% of specimens, the lymph node is completely replaced by lymphoma. Areas of coagulative necrosis can be present. In some tumors, the neoplastic cells tend to congregate around blood vessels, and this is a helpful histologic clue for considering the diagnosis of ALK+ ALCL (Fig. 75.4) (20). In a small subset of cases, the lymph node capsule is thickened and fibrous bands extend into the lymph node, dividing the neoplasm into nodules that superficially resemble nodular sclerosis Hodgkin lymphoma (Fig. 75.5) (21).

these neoplasms. In approximately 50% to 60% of specimens, the lymph node is completely replaced by lymphoma. Areas of coagulative necrosis can be present. In some tumors, the neoplastic cells tend to congregate around blood vessels, and this is a helpful histologic clue for considering the diagnosis of ALK+ ALCL (Fig. 75.4) (20). In a small subset of cases, the lymph node capsule is thickened and fibrous bands extend into the lymph node, dividing the neoplasm into nodules that superficially resemble nodular sclerosis Hodgkin lymphoma (Fig. 75.5) (21).

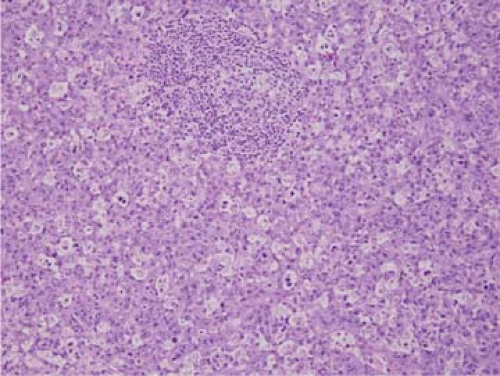

Cytologically, the most common variant of ALK+ ALCL, the classical variant, represents 70% to 80% of all cases (1,5,7,22). In this variant, the neoplastic cells tend to be cohesive, forming clusters and sheets, and are highly pleomorphic. The cytoplasm is abundant and amphophilic or deeply basophilic. The nuclei can be round, lobulated, or have bizarre shapes. So-called hallmark cells are usually present. These cells have a “horseshoe” or “pig embryo” shaped nucleus that partially surrounds a cytoplasmic, pale-staining, paranuclear hof (Fig. 75.6). In some cases, neoplastic cells are giant sized and multinucleated with wreath-like nuclei. The nucleoli can be small or prominent; in some cases, the nucleoli can be inclusion-like resembling Hodgkin cells. The mitotic rate is high, and atypical mitotic figures are common. In fine needle aspiration smears and touch imprints, ALK+ ALCL cells are usually large and often have basophilic cytoplasm with prominent vacuoles (Fig. 75.7). The nuclei are round or lobated, nuclear chromatin is clumped, and nucleoli are often prominent. Binucleated or multinucleated cells are common, and hallmark cells can be recognized (6,23).

Figure 75.3. ALK+ anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, classical variant. In this field, the neoplasm has a starry-sky pattern and surrounds a residual lymphoid follicle. Hematoxylin-eosin stain. |

The term anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, although descriptively accurate for the classical variant, has its shortcomings for some of the other histologic variants of ALK+ ALCL in which the neoplastic cells are either not large or not anaplastic (6). These variants represent up to 25% of cases of ALK+ ALCL. The two most common are the lymphohistiocytic and small-cell variants, each occurring in 5% to 10% of cases (22,24). Other variants of ALK+ ALCL described in the literature include the monomorphic, sarcomatoid, giant cell–rich, granulation tissue– or nodular fasciitis–like, Hodgkin lymphoma–like, eosinophil-rich, and neutrophil-rich variants (6,22,25,26,27,28).

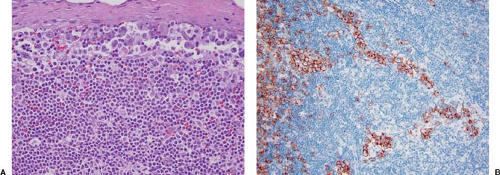

In the lymphohistiocytic variant of ALK+ ALCL, the neoplastic cells are outnumbered by numerous reactive small lymphocytes and histiocytes (Fig. 75.8). A particularly useful histologic clue to the diagnosis is the fact that the neoplastic cells tend to line up around blood vessels (20,22). In addition, many of the neoplastic cells are cytologically similar to the neoplastic cells seen in the classical variant, including hallmark cells, particularly around blood vessels. In the small-cell variant of ALK+ ALCL, many of the neoplastic cells are small and do not resemble the cells typically observed in classical variant cases (Fig. 75.9). However, complete analysis of the entire tumor often shows small foci or single, more typical large anaplastic cells. The small-cell variant is also rarely present in a pure pattern; it often occurs with areas of the lymphohistiocytic variant.

The descriptive names for the other variants of ALK+ ALCL are self-explanatory. In the monomorphic variant, many of the neoplastic cells resemble the cells of large-cell lymphoma or poorly differentiated plasmacytoma. If a starry-sky pattern is prominent, the low-power appearance of the neoplasm may superficially resemble Burkitt lymphoma (Fig. 75.3). Usually, some areas of the classical variant of ALK+ ALCL are also present in these neoplasms, but these areas can be focal. In the

sarcomatoid variant, the neoplastic cells are spindle-shaped, and these neoplasms can closely resemble sarcoma (Fig. 75.10). The presence of small reactive lymphocytes intermixed with the spindled neoplastic cells is a clue against the diagnosis of sarcoma. In the giant cell–rich variant, many of the neoplastic cells are gigantic and multinucleated. In the granulation tissue–like variant, the neoplastic cells are accompanied by abundant edema and/or myxoid stroma (Fig. 75.4). Cases of ALK+ ALCL that resemble nodular sclerosis Hodgkin lymphoma have been described (Fig. 75.5) (21). Cases of ALK+

ALCL can be rich in either eosinophils, neutrophils, or a mixture of both.

sarcomatoid variant, the neoplastic cells are spindle-shaped, and these neoplasms can closely resemble sarcoma (Fig. 75.10). The presence of small reactive lymphocytes intermixed with the spindled neoplastic cells is a clue against the diagnosis of sarcoma. In the giant cell–rich variant, many of the neoplastic cells are gigantic and multinucleated. In the granulation tissue–like variant, the neoplastic cells are accompanied by abundant edema and/or myxoid stroma (Fig. 75.4). Cases of ALK+ ALCL that resemble nodular sclerosis Hodgkin lymphoma have been described (Fig. 75.5) (21). Cases of ALK+

ALCL can be rich in either eosinophils, neutrophils, or a mixture of both.

Figure 75.5. ALK+ anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. A: In this case, nodules of neoplasm are separated by fibrous bands superficially resembling nodular sclerosis Hodgkin lymphoma. B: High-power magnification of large lymphoma cells. C: The lymphoma cells are strongly positive for ALK with a cytoplasmic pattern of staining. A, B, hematoxylin-eosin stain; C, immunohistochemistry with hematoxylin counterstain.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|