, Arthur H. Cohen2, Robert B. Colvin3, J. Charles Jennette4 and Charles E. Alpers5

(1)

Department of Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA

(2)

Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California, USA

(3)

Department of Pathology Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

(4)

Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA

(5)

Department of Pathology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA

Abstract

Amyloidosis (AL type) is conceptually similar to light chain deposit disease in many respects [1]. It represents the systemic deposition of a structurally altered light and/or heavy chain; it is more common than light chain deposit disease. Amyloid may also be due to deposition of proteins, other than immunoglobulin light or heavy chains, that form beta-pleated sheets. These include serum AA, apolipoprotein A-1, apolipoprotein A-IV, transthyretin, fibrinogen, beta-2 microglobulin, and leukocyte chemotactic factor 2, among many others [2]. Most patients with glomerular amyloid present with heavy proteinuria and approximately 50 % have concurrent renal insufficiency. Interstitial or vascular (nonglomerular) amyloid morphologically is similar to amyloid in other locations; in the absence of glomerular amyloid, its detection requires a reasonably high level of suspicion on the part of the pathologist. Isolated interstitial amyloid is usually manifested by some degree of renal insufficiency; “pure” vascular amyloid may be clinically silent or may be associated with renal functional impairment.

Introduction/Clinical Setting

Amyloidosis (AL type) is conceptually similar to light chain deposit disease in many respects [1]. It represents the systemic deposition of a structurally altered light and/or heavy chain; it is more common than light chain deposit disease. Amyloid may also be due to deposition of proteins, other than immunoglobulin light or heavy chains, that form beta-pleated sheets. These include serum AA, apolipoprotein A-1, apolipoprotein A-IV, transthyretin, fibrinogen, beta-2 microglobulin, and leukocyte chemotactic factor 2, among many others [2]. Most patients with glomerular amyloid present with heavy proteinuria and approximately 50 % have concurrent renal insufficiency. Interstitial or vascular (nonglomerular) amyloid morphologically is similar to amyloid in other locations; in the absence of glomerular amyloid, its detection requires a reasonably high level of suspicion on the part of the pathologist. Isolated interstitial amyloid is usually manifested by some degree of renal insufficiency; “pure” vascular amyloid may be clinically silent or may be associated with renal functional impairment.

Pathologic Findings

Light Microscopy

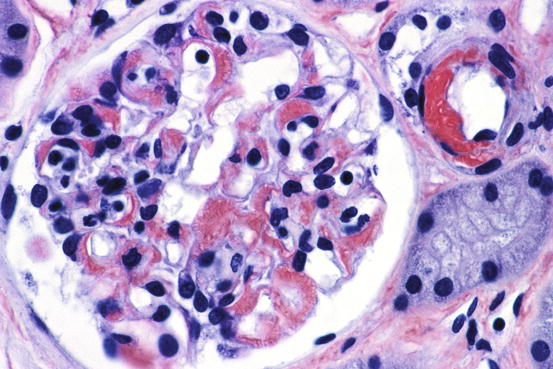

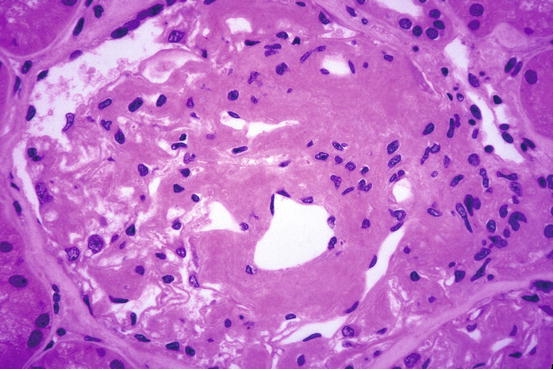

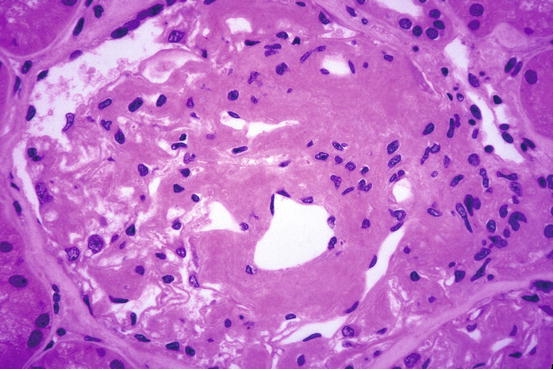

Amyloid appears as amorphous acellular, pale eosinophilic material in the mesangium and extending out to glomerular capillary walls in some patients (Fig. 18.1). The capillary wall deposits may appear as silver positive fringe-like projections, longer than those seen in membranous glomerulopathy. Arterioles and arteries frequently show amyloid deposits as well. The renal pathologic features of other varieties of amyloid (e.g., AA, hereditary forms) are virtually identical in most respects to AL amyloid [1, 3]. Specific diagnosis is made by positive Congo red stain, with apple-green birefringence under polarized light (Figs. 18.2 and 18.3).

Fig. 18.1

Amyloid with glomerulus and arteriole infiltrated by homogeneous acellular material replacing normal structures [periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain]