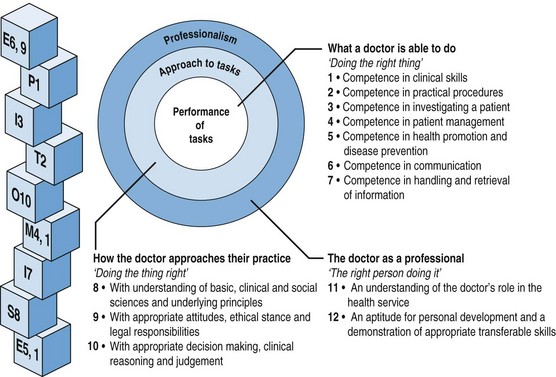

Chapter 12 This has led to a shift of focus and the development of teaching initiatives in a variety of ambulatory care venues (Bardgett & Dent 2011, Dent 2003, Dent 2005, Dent et al 2007). • outpatient clinics in a variety of specialties • multiprofessional clinics where staff from a variety of disciplines see patients together, e.g. an oncology clinic, which may include surgery, radiotherapy and medical oncology • sessions provided by other healthcare professionals, e.g. physiotherapy, occupational therapy. But other venues in the hospital may be available to provide suitable opportunities: • clinical investigation unit, e.g. endoscopy suite • nurse-led clinics, e.g. for pre-assessment of surgical admissions, audiology assessment, allergy testing However, finding a new, suitable venue is one thing; finding the budget to run a new programme in it is another. Finances may be required to support a new teaching programme, produce study guides or logbooks, provide clinical tutor sessions or reimburse patients’ travelling expenses (Dent et al 2001b). Opportunities for student learning with inpatients in hospital wards is usually focused on: In ambulatory care settings, however, patients are seen closer to their own social circumstances and environment, as their attendance in an ambulatory facility is part of a continuum in the management of their illness, often in the context of the contribution from other HCPs and community support services (Stearns & Glasser 1993). Ambulatory care learning can therefore include opportunities for students to gain experience in: Practically all learning outcomes can be experienced in ambulatory care teaching venues (see Chapter 18, Outcome-based education). Finally the ambulatory venue is more likely to provide opportunities for: An ACTC (Dent et al 2001a) can give students the opportunity to meet selected patients with problems relevant to their stage of learning and with timetabled clinical tutors who are not at the same time being required to provide patient care. A ‘content expert’ in the appropriate body-system is not necessarily required for much of the teaching; in fact, the ACTC is a good venue for peer-assisted learning programmes (see Chapter 16). Students may rotate among different tutors who can supervise different activities such as history taking, physical examination and procedural skills. At the University of Otago, Dunedin, an ambulatory care teaching resource has been created to provide fourth-year students with the opportunity to see a variety of invited patients illustrating clinical conditions in particular organ systems. Students appreciated the dedicated and structured teaching time in a learner-friendly environment (Latta et al 2011). Early clinical contact is a feature of innovative curricula (GMC 2009, Harden et al 1984). As hospital wards may no longer have patients with common clinical problems who are sufficiently well to see students, ambulatory care can offer a wide range of suitable clinical opportunities for undergraduate at all stages of learning. Less experienced students who are still developing their communication and examination skills can practise these in the dedicated teaching environment of the ACTC, which provides a ‘bridge’ between practising with simulated patients and manikins in the clinical skills centre and exposure to real patients in the busy environment of an everyday outpatient department. In the later clinical years, when students have more extensive clinical experience, placement in routine clinics may be more appropriate. In these circumstances students can often learn as apprentices as part of the clinical team (Worley et al 2000). It is important to organize the content of an ambulatory care session so that students can easily identify the educational opportunities available. The EPITOMISE logbook, based on the learning outcomes of the Scottish doctor (Simpson et al 2002), has been used to focus student learning on the learning opportunities related to the various patients seen. With every patient they meet, students are asked three questions: They then document their experiences under each learning outcome point and reflect on what further learning needs they can now identify and how they will address these learning needs (Dent & Davis 1995) (Table 12.1 and Fig. 12.1). Table 12.1 The EPITOMISE acronym helps students to look for all learning outcomes in any patient encounter Fig. 12.1 EPITOMISE logbook links students’ clinical experience in any venue to the curriculum learning outcomes of the Scottish doctor. Additional tasks for future learning can then be built around each. ‘Focus scripts’ described by Peltier and colleagues (2007) are used to facilitate the learning of history taking and physical examination skills. Similarly, using the patient journey as a model, students may be directed to follow a patient through a series of ambulatory care experiences from the outpatient department, through clinical investigations and pre-operative assessment, to the day surgery unit and follow-up clinic (Hannah & Dent 2006).

Ambulatory care teaching

Introduction

Identifying new resources for ambulatory care teaching

What can be taught and learned in ambulatory care settings?

Role of a dedicated Ambulatory Care Teaching Centre (ACTC)

When should ambulatory care teaching be provided?

Structured learning in ambulatory care venues

Logbooks

E

ethics and enquiry (communications skills)

P

physical examination

I

investigations and interpretations of results

T

technical procedures

O

options of diagnosis, clinical judgement

M

management and multidisciplinary team

I

information handling

S

sciences, basic and clinical

E

education of the patient and yourself

Task-based learning

Case studies

Ambulatory care teaching