Patient Story

Theresa is a 39-year-old, white, single woman who presents with insomnia and depression. After exploring the presenting symptoms, her physician reviews some screening questions about potentially related problems. In response to a question about heavy drinking in the past year, Theresa responds that she is drinking about 2 bottles (10 drinks) of wine nightly. She acknowledges going over limits repeatedly and a persistent desire to quit or cut down, as well as continuing to drink in spite of hangovers and nausea in the morning. She denies withdrawal symptoms, driving while intoxicated, job or serious relationship problems, but admits that her social activities have decreased over the past year because she spends her evening drinking alone. No one else knows she is struggling with drinking. Her depression and insomnia started after her drinking increased about 2 years ago.

Introduction

Excessive drinking of alcohol is a common behavior encountered in primary care, yet few clinicians feel prepared to address it. Most clinicians are unclear about the best way to screen for heavy drinking and lack confidence in how to address it. Physicians often lack the knowledge and skill to screen and evaluate excessive drinking, let alone address it other than suggesting a referral to an addiction counselor or treatment program. Regrettably, few patients are appropriate for or accept referral to a counselor or program. Fortunately, research over the past 20 years has provided evidence-based, efficient ways to screen, evaluate, and treat heavy drinking in primary care.

Synonyms (Terminology)

Epidemiology

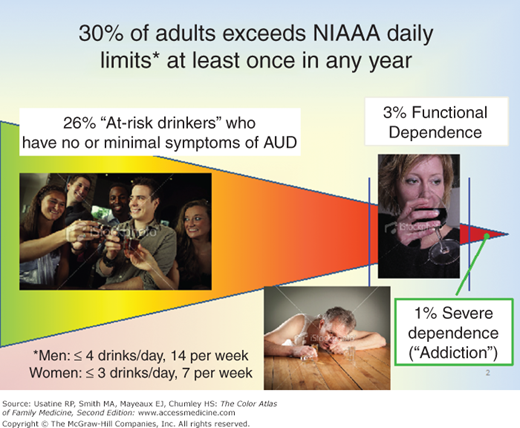

- In any given year, approximately 30% of U.S. adults 18 years of age and older exceed the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) low-risk drinking guidelines at least once (Figures 237-1 and 237-2).1 The low-risk drinking limits for healthy adult women is defined as drinking no more than 3 drinks in any day and 7 drinks in any week, and for men, no more than 4 drinks in any day and 14 drinks in any week.

- A drink refers to 12 oz of beer, 5 oz of wine or 1.5 oz of spirits, each of which contains about 14 g of absolute ethanol.1 Within that group, the frequency varies from occasional to daily or near daily, and the amount of drinking varies from 5 to more than 20 drinks daily. Most excessive drinkers who exceed the limits (72%) do not meet diagnostic criteria for an alcohol use disorder and are considered at-risk drinkers.1

- At-risk drinkers are analogous to asymptomatic patients with hyperlipidemia or hypertension: they do not currently have a disorder (other than the risk factor) but are at elevated risk for developing one if the risk factor is not decreased. Reduction in excessive drinking significantly reduces risk of developing an alcohol use disorder, liver disease, or social problems.2

- Approximately 4% of adults meet Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) criteria for alcohol dependence in any year.3 Three-quarters of them have functional alcohol dependence, which is characterized by a predominance of “internal symptoms” of impaired control such as going over limits and persistent desire to quit or cut down and a limited course. People with functional alcohol dependence have a single episode, lasting on average 3 to 4 years, usually with resolution of the episode and no recurrence. A quarter of those with dependence, 1% of the general population in any year, have recurrent alcohol dependence, demonstrating an average of 5 episodes over a period of years to decades.4

- Thus, there are 3 categories of heavy drinkers the primary care provider is apt to encounter (Box 237-1):

At-risk drinkers (the predominant group);

functional alcohol dependence; and

recurrent, more severe alcohol dependence.

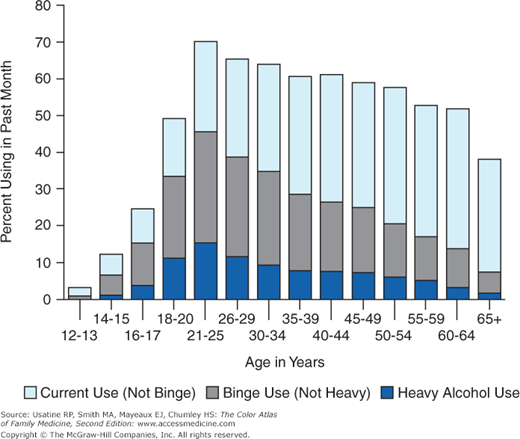

Figure 237-2

Past month use of alcohol among U.S. residents over age 12. Category definitions: Current (past month) use—at least 1 drink in the past 30 days; binge use—5 or more drinks on the same occasion (i.e., at the same time or within a couple of hours of each other) on at least 1 day in the past 30 days; heavy use—5 or more drinks on the same occasion on each of 5 or more days in the past 30 days.

Diagnosis of Alcohol Use Disorder | |

|---|---|

Category | Common Presentation |

At-risk drinkers | None or driving while drinking only (no DWI) |

Functional alcohol use disorder |

|

Severe recurrent alcohol use disorder |

|

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Alcohol use disorder is a heritable disease: Approximately 50% of the risk is genetic, while environmental factors account for the remainder, the most clearly established factor being early childhood abuse or neglect.5,6 Multigenerational alcohol dependence often appears in the early to mid-teens, but functional alcohol dependence can begin at any age.7

Risk Factors

- Family history of alcohol dependence,8 and

- Early life stress in the form of early childhood abuse or neglect.9

- An early history of externalizing personality factors, such as:

- Extroversion

- Attention deficit disorder

- Oppositional defiant disorder

- Conduct disorder

- Extroversion

- Antisocial and borderline personality disorders among adults10

Onset of drinking before the age of 14 years markedly increases risk for later development of alcohol dependence, especially for adolescents with a positive family history.11

Diagnosis

- Contrary to common belief, heavy drinkers are very likely to answer questions about their drinking honestly, provided the questions are skillful. Asking about quantity and frequency (“On any single occasion during the past 3 months, have you had more than 5 drinks containing alcohol?”) is most likely to elicit an informative answer, whereas any question that suggests even the possibility of moral judgment (e.g., “How much do you drink?”) is less likely to yield helpful answers. Box 237-2 for the specific screening question recommended by the NIAAA.

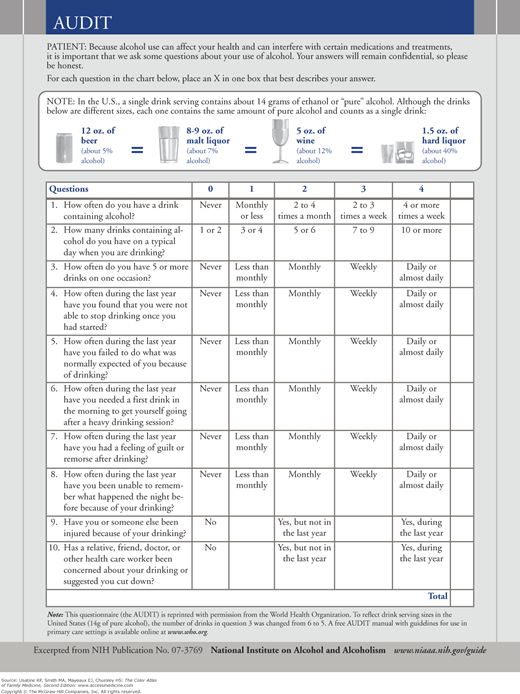

- Most heavy drinkers are not symptomatic. Thus, they do not have alcohol-related symptoms. They can only be detected through screening for quantity and frequency of drinking. Screening focused on symptoms of alcohol use disorder, such as the well-known CAGE (“Have you ever tried to cut down on your drinking? Have you ever felt annoyed by criticism of your drinking? Have you ever felt guilty about your drinking? Have you ever had a morning eye-opener?”), will not detect asymptomatic at-risk drinkers, and it performs poorly compared to almost all other methods.12 It is important to inquire about quantity and frequency of drinking in order to identify at-risk drinkers and patients with functional alcohol dependence. The AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test) (Figure 237-3) is the gold standard for a written questionnaire; it only takes about 3 minutes to complete and is easy to score. A score of 8 or more for men or 4 or more for women suggests excessive drinking.1

- Current diagnostic criteria are based on the DSM-IV.13 DSM-IV specifies 2 types of alcohol use disorder: abuse and dependence. However, since that manual was published, research on the epidemiology of alcohol use disorders and clustering of clinical signs and symptoms has failed to confirm the differentiation of these 2 disorders. Current research supports instead the presence of a single disorder that includes the criteria of both abuse and dependence under DSM-IV into a single dimensional diagnosis.14 The proposed criteria for the next edition, DSM-V, currently under consideration, have a single disorder, alcohol use disorder. The presence of any 2 of 11 criteria (Box 237-3) is enough to establish a diagnosis, where the number of criteria met are highly correlated with severity of the disorder.15 Although there may be some minor modifications, it is almost certain that in the final version, there will be a single diagnostic category. Note that serious medical, social or personal complications of heavy drinking, such as employment or school problems, serious family or marital disruptions or legal problems are not required for a diagnosis. DSM-IV alcohol dependence criteria are usually among the earliest to occur, while most abuse criteria such as serious interpersonal, vocational or legal problems only occur among a relatively small group of the most severely affected.16 Thus, in this chapter the terms alcohol use disorder (AUD) and alcohol dependence are used interchangeably.

- According to NIAAA, healthy adult men should not drink in excess of 4 standard U.S. drinks in any day, or 14 in any week, and adult women should not exceed 3 drinks in any day and 7 in any week.1 Low-risk drinking limits may be less for certain groups, such as adults older than age 65 years, or in the presence of medical illnesses, such as liver disease. Women who are pregnant or are trying to become pregnant should be advised to abstain completely.

- Drinking in excess of these limits is considered unhealthy, placing heavy drinkers at elevated risk for developing AUD and associated complications such as liver disease.17 Approximately 30% of U.S. adults age 18 years and older drink in excess of low-risk limits at least once in any year. About 4 of 5 of them do not meet diagnostic criteria for a disorder, and are considered to be “at-risk” for developing one.1 In other words, this group has an asymptomatic risk factor similar to hypertension or hyperlipidemia. At-risk drinkers are typically unaware that their drinking constitutes a health risk. This does not reflect “denial” but rather the lack of information available to the public about what constitutes high-risk drinking or how to measure consumption. For example, how many standard U.S. drinks are in a 7 oz. martini? (Depending on the specific way it is mixed, the answer is about 4.) It is much easier to obtain dietary information about food than information about alcohol content in a beverage.

- Patients with functional alcohol dependence are aware of struggling with their alcohol consumption, but lack serious life consequences at this time. Most are open to changing their drinking, but they may need to be identified through screening, rather than presenting with this problem.

- Patients with more severe, recurrent alcohol dependence often present with intoxication, withdrawal, or medical complications of heavy drinking, such as liver disease or pancreatitis. If these disorders are present, they demonstrate the expected physical manifestations. Like other patients with chronic, treatment-refractory illness, they have a chronic course, with periodic relapses or even with ongoing chronic illness.

How many times in the past year have you had…

One standard drink is equivalent to 12 oz of beer, 5 oz of wine, or 1.5 oz of 80-proof spirits. |

Figure 237-3

The AUDIT questionnaire. Scores are added to determine the total. Positive screens are indicated by total scores ≥8 in men and ≥4 in women. Higher scores indicate more severe alcohol involvement. Scores >16 suggest the possibility of alcohol dependence.1,39

Proposed DSM-V (Updated April 30, 2012) A. A problematic pattern of alcohol use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress. B. Two (or more) of the following occurring within a 12-month period:

|

- In a given year, 30% of the adult U.S. population engages in unhealthy drinking at least once (Figure 237-1). In an average primary care practice, approximately 10% to 15% of outpatients are heavy drinkers.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree