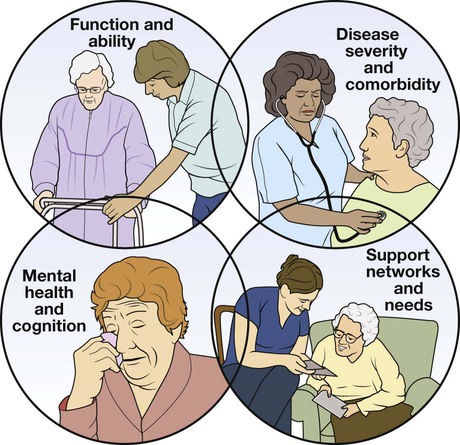

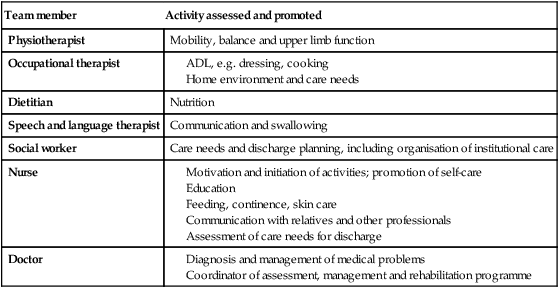

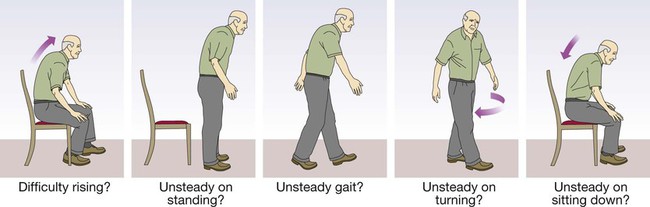

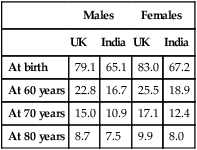

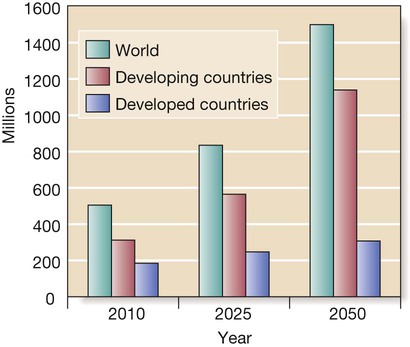

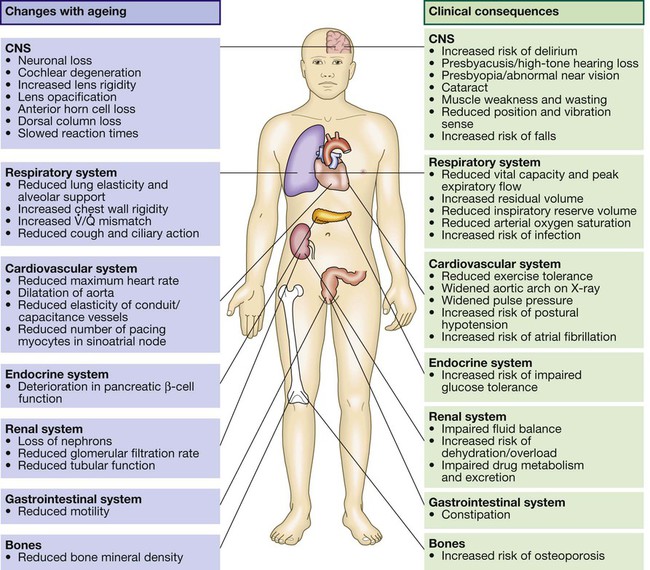

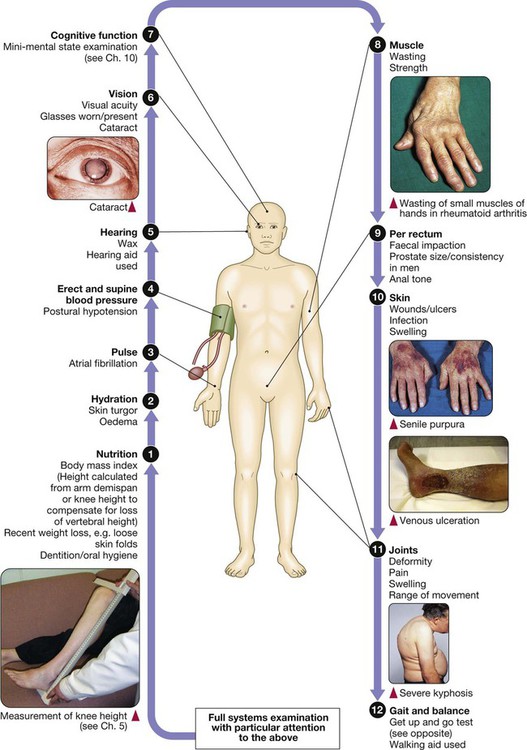

• Ensure the patient can hear. • Establish the speed of onset of the illness. • If the presentation is vague, carry out a systematic enquiry. all drugs, especially any recent prescription changes past medical history, even from many years previously • Obtain a collateral history: confirm information with a relative or carer and the general practitioner, particularly if the patient is confused or communication is limited by deafness or speech disturbance. • Thorough to identify all comorbidities. • Tailored to the patient’s stamina and ability to cooperate. Sweeping demographic change has meant that older people now represent the core practice of medicine in many countries. A good knowledge of the effects of ageing and the clinical problems associated with old age is thus essential in most medical specialties. The older population is extremely diverse; a substantial proportion of 90-year-olds enjoy an active healthy life, while some 70-year-olds are severely disabled by chronic disease. The terms ‘chronological’ and ‘biological’ ageing have been coined to describe this phenomenon. Biological rather than chronological age is taken into consideration when making clinical decisions about, for example, the extent of investigation and intervention that is appropriate. Geriatric medicine is concerned particularly with frail older people, in whom physiological capacity is so reduced that they are incapacitated by even minor illness. They frequently have multiple comorbidities, and acute illness may present in non-specific ways, such as confusion, falls or loss of mobility and day-to-day functioning. These patients are prone to adverse drug reactions, partly because of polypharmacy and partly because of age-related changes in responses to drugs and their elimination (p. 36). Disability is common, but patients’ function can often be improved by the interventions of the multidisciplinary team (p. 167). Life expectancy in the developed world is now prolonged, even in old age (Box 7.1); women aged 80 years can expect to live for a further 10 years. However, rates of disability and chronic illness rise sharply with ageing and have a major impact on health and social services. In the UK, the reported prevalence of a chronic illness or disability sufficient to restrict daily activities is around 25% in those aged 50–64, but is 66% in men and 75% in women aged over 85. Although the proportion of the population aged over 65 years is greater in developed countries, two-thirds of the world population of people aged over 65 live in developing countries at present, and this is projected to rise to 75% in 2025. The rate of population ageing is much faster in developing countries (Fig. 7.1) and so they have less time to adjust to its impact. • Nuclear chromosomal DNA, causing mutations and deletions which ultimately lead to aberrant gene function and potential for malignancy. • Telomeres, which are the protective end regions of chromosomes which shorten with each cell division because telomerase (which copies the end of the 3′ strand of linear DNA in germ cells) is absent in somatic cells. When telomeres are sufficiently eroded, cells stop dividing. It has been suggested that telomeres represent a ‘biological clock’ which prevents uncontrolled cell division and cancer. Telomeres are particularly shortened in patients with premature ageing due to Werner’s syndrome, in which DNA is damaged due to lack of a helicase. • Mitochondrial DNA and lipid peroxidation, resulting in reduced cellular energy production and ultimately cell death. • Proteins – e.g. those increasing formation of advanced glycosylation end-products from spontaneous reactions between proteins and sugars. These damage structure and function of the affected protein, which becomes resistant to breakdown. The effects of ageing are usually not enough to interfere with organ function under normal conditions, but reserve capacity is significantly reduced. Some changes of ageing, such as depigmentation of the hair, are of no clinical significance. Figure 7.2 shows many factors that are clinically important. It is important to understand the difference between ‘disability’, ‘comorbidity’ and ‘frailty’. Disability indicates established loss of function (e.g. mobility; see Box 7.13, p. 176), while frailty indicates increased vulnerability to loss of function. Disability may arise from a single pathological event (such as a stroke) in an otherwise healthy individual. After recovery, function is largely stable and the patient may otherwise be in good health. When frailty and disability coexist, function deteriorates markedly even with minor illness, to the extent that the patient can no longer manage independently. Similarly, comorbidity (the number of diagnoses present) is not equivalent to frailty; it is quite possible to have several diagnoses without major impact on homeostatic reserve. Unfortunately, the term ‘frail’ is often used rather vaguely, sometimes to justify a lack of adequate investigation and intervention in older people. However, it can be specifically identified by assessing function in a number of domains. Two main approaches to evaluating frailty exist: measurement of physiological function across a number of domains (e.g. the Fried Frailty score, Box 7.2), or a score based on the number of deficits or problems – for example, the Rockwood score. Although not strictly an investigation, one of the most powerful tools in the management of older people is the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment, which identifies all the relevant factors contributing to their presentation (p. 166). In frail patients with multiple pathology, it may be necessary to perform the assessment in stages to allow for their reduced stamina. The outcome should be a management plan that not only addresses the acute presenting problems, but also improves the patient’s overall health and function (Box 7.3). Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment is performed by a multidisciplinary team (p. 167). Such an approach was pioneered by Dr Marjory Warren at the West Middlesex Hospital in London in the 1930s; her comprehensive assessment and rehabilitation of supposedly incurable, long-term bedridden older people revolutionised the approach of the medical profession to older, frail people and laid the foundations for the modern specialty of geriatric medicine.

Ageing and disease

Comprehensive geriatric assessment

History

Examination

Demography

Functional anatomy and physiology

Biology of ageing

Physiological changes of ageing

Frailty

Investigations

Comprehensive geriatric assessment

Ageing and disease