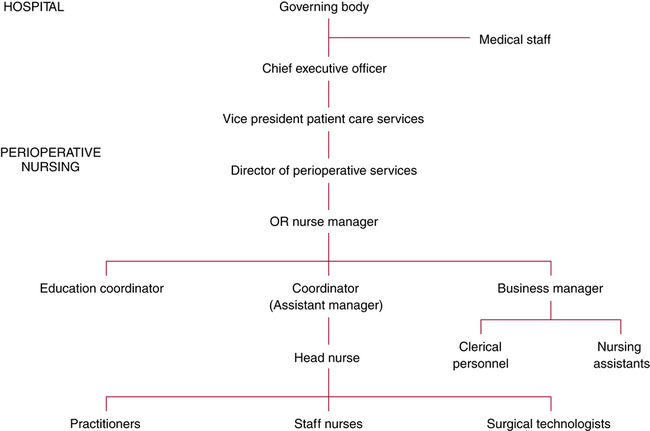

Chapter 6 After studying this chapter, the learner will be able to: • Define the role of the perioperative management team. • Describe the relationship between the perioperative environment and other patient care departments. • Define the role of intradepartmental surgical services committees. The perioperative patient care team surrounds the patient throughout the perioperative experience. This direct perioperative patient care team functions within the physical confines of the OR, which is one part of the physical facilities that make up the total perioperative environment. Other areas in the perioperative environment include preadmission testing (PAT), the ambulatory services unit (ASU), and the postanesthesia care unit (PACU). Similarly, the perioperative patient care team makes up only one part of the human activity directed toward the care of the surgical patient. Many article reviews and up-to-date notices for managers can be found at AORN Management Connections at www.aorn.org/News/Managers. This leadership-based managerial online newsletter on the AORN website (www.aorn.org) keeps the manager informed of many new developments in the perioperative arena. The Magnet Recognition Program was founded in 1993 by the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC) as a way to improve health care management, staffing, and outcomes. Magnet recognition is the highest acknowledgment on a national level of ongoing nursing care excellence. Detailed information and a visual diagram are available at www.nursecredentialing.org/magnet.aspx. Activities in a Magnet hospital are highly visible to the public and point to 14 forces that form the core values of this distinguished title (Box 6-1). The five primary hallmarks of Magnet status include the following: 1. Transformational leadership: Demonstrated vision, influence, clinical knowledge, and expertise in professional nursing practice. 2. Structural empowerment: Mission, values, and vision are manifest in outcomes through professional partnerships and collaborations with the staff. 3. Exemplary professional practice: Application of the nursing process and the emergence of new knowledge are reflected with the response from patients, families, the team, and the community at large. This is a circular process. 4. New knowledge: Innovation and improvement: Continual implementation of improved methods helps to refine the system through evidence-based practice. Individualized care uses a blend of new and old techniques. 5. Empirical quality outcomes: The end result of care is compared with benchmarks established along the way. Making a difference is emphasized through innovation and creativity. Standards still remain, but flexibility is key to gaining new learning directed at improved outcomes. A formal application is preceded by an analysis of current workplace status. The nursing division must be part of a larger health care organization. A manual is available from the ANCC website (www.nursecredentialing.org/magnet.aspx) to assist in determination of eligibility. The process includes a written documentation phase and a site visit by the Magnet recognition appraisal committee. The site visit is funded totally by the applicant organization. The Commission on Magnet Recognition renders a decision concerning status within 4 to 6 weeks of the site visit and a review of all application documentation. Magnet recognition is effective for 4 years, during which time spot inspections may be made to assess for variances. Some prerequisites to application include but are not limited to the following requirements: 1. Data collection concerning quality and outcomes must become part of a national database for benchmarking nurse-sensitive quality indicators at the patient care division level. 2. Educational preparation of nursing administration: a. The Chief Nursing Officer (CNO) is required to be Master’s prepared when the application is submitted. The Baccalaureate or Master’s degree may be in nursing. The CNO must participate in the highest structural governance and be ultimately responsible for all nursing divisions. b. By January 2011, a Baccalaureate degree in nursing is required for 75% of nurse managers at the time of application. c. By 2012, all nurse managers are required to have a Baccalaureate degree in nursing. 3. ANCC’s Scope and Standards for Nurse Administrators must be in effect for adequate measuring and surveying by Magnet site visitors. 4. The organization must be in full compliance with all local, state, and federal laws and regulations. 5. Compliance with National Safety Patient Goals from The Joint Commission (TJC) is required. 6. Policies and procedures must be in place to permit nurses to voice concerns concerning practice environment without retribution. 7. In the previous 3 years, no complaints of unfair labor practices can have been filed by nurses or be pending before the National Labor Relations Board or other federal or state court. Nursing care is more clearly defined, which offers the opportunity for professional growth and enrichment and thereby supports recruitment and retention of staff.2,5,7 Nursing turnover is minimized. Nursing administrators remain with the organization, which in turn provides a stable managerial environment. Magnet status can be highly publicized and prized by the marketing department of the facility. Reimbursement sources recognize the credential and use the facility as a referred recommendation to insured groups. The public views the credential as a reassuring atmosphere of safe efficient care. Personnel should know the direction of the entire organizational effort as a prerequisite for successful functioning. Administrative personnel interpret hospital and departmental philosophy, objectives, policies, and procedures to the perioperative staff.3,9 These terms are defined as follows: 1. Philosophy: Statement of beliefs regarding patient care and the nature of perioperative nursing that clarifies the overall responsibilities to be fulfilled. 2. Objectives: Statements of specific goals and purposes to be accomplished during the course of action and definitions of criteria for acceptable performance. 3. Policies: Specific authoritative statements of governing principles or actions, within the context of the philosophy and objectives, that assist in decision making by providing guidelines for action to be taken or, in some situations, for what is not to be done. a. Basic policies: Statements of the principles of the administration and its approach to functioning. Examples include disallowing smoking by anyone on facility premises. b. General policies: Guidelines of the principles dealing with everyday situations that affect all personnel within the hospital. Examples include requiring all personnel, regardless of role, to be certified in CPR. c. Departmental policies: Guidelines structured to meet the needs of a specific work unit (e.g., OR policies). Examples include dress codes for specific areas. 4. Procedures: Statements of task-oriented and skill-oriented actions to be taken in the implementation of policies. 1. TeamSTEPPS was developed for the Department of Defense Patient Safety Program in collaboration with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. It includes core values of teamwork such as leadership, situation monitoring, mutual support, and communication. The outcomes affect performance, knowledge, and attitudes. Detailed information can be found at http://teamstepps.ahrq.gov/. 2. Leadership organizes and articulates clear goals. Decisions are made with input from team members, who feel empowered enough to speak when information needs to be imparted to the group. Team relations are supported, and conflicts are resolved. Events are planned, problems are solved, and performance is improved by evaluating processes. 3. Situation monitoring (STEP: Status of patient, Team members, Environment, and Progress toward goal) is an ongoing process of constant vigilance for progress or regress of goal attainment. 4. Mutual support is actively given and received by all team members. Feedback is timely, considerate, and respectful. Information exchanged is specific and directed toward improvement of team performance. Concerns should be voiced and should elicit a response to be certain of successful communication.1 If a situation is an essential safety breach, any team member may “stop the line,” meaning that the activity or procedure immediately halts without fear of repercussions. The goal is still met without compromising relationships. 5. Communication ranges from basic information to critical dialogue. One structured communication technique uses SBAR (Situation: What is going on with the patient? Background: What is the clinical context or history related to the patient? Assessment: What is the presumed problem? Recommendation and request: What can we or I do immediately to correct the situation?) The manager implements and enforces hospital and departmental policies and procedures. He or she also analyzes and evaluates continuously all patient care services rendered and, through participation in research, seeks to improve the quality of patient care given. The manager retains accountability for all related activities in the perioperative environment.9 The scope of this accountability includes the following: • Provision of competent staff and supportive services that are adequately prepared to achieve quality patient care objectives. • Delegation of responsibilities to professional nurses and assignment of duties to other patient care personnel. • Responsibility for evaluation of the performance of all departmental personnel and for assessment and continuous improvement of the quality of care and services. • Provision of educational opportunities to increase knowledge and skills of all personnel. • Coordination of administrative duties to ensure proper functioning of staff. • Provision and fiscal control of materials, supplies, and equipment. • Coordination of activities between the perioperative environment and other departments. • Creation of an atmosphere that fosters teamwork and provides job satisfaction for all staff members. • Identification of problems and resolution of those problems in a decisive timely manner. • Initiation of data collection and analyses to develop effective systems and to monitor efficiency and productivity. The duties of the head nurse include, but are not limited to, the following: • Planning for and supervising patient care activities within the OR suite or specific room(s) to which he or she is assigned. • Coordinating patient care activities with the surgeons and anesthesia providers. • Maintaining adequate supplies and equipment and providing for their economic use. • Observing the performance of all staff members and providing feedback. • Interpreting the policies and procedures adopted by the department and hospital administration. • Informing the perioperative manager of needs and problems that arise in the department and assisting with problem solving. Every hospital has a governing body that appoints a chief executive officer (CEO), usually with the title of hospital administrator, to provide appropriate physical resources and personnel to meet the needs of patients. Administrative lines of authority, responsibility, and accountability are defined to establish the working relationships among departments and personnel (Fig. 6-1).

Administration of perioperative patient care services

Establishing administrative roles

Magnet recognition

Leading the way to magnet status

Eligibility for magnet status

Benefits of magnet status

Management of surgical services

Perioperative administrative personnel

Perioperative nurse manager

People skills and communications.

Managerial responsibilities

Head nurse or charge nurse

Interdepartmental relationships

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine

Website

Website