Chapter Forty-Eight. Adaptation to extrauterine life 1

haematological, cardiovascular, respiratory and genitourinary considerations

Introduction

Chapter 48, Chapter 49, Chapter 50, Chapter 51, Chapter 52 and Chapter 53 explore some of the physiological mechanisms fundamental to the adaptation to extrauterine life and highlight common pathophysiological changes that augment adaptation to extrauterine life. Understanding these complex anatomical features and physiological processes provides a foundation for competent assessment of neonates and enables practitioners to draw conclusions about neonatal health. To ensure clarity in the ensuing discussion the masculine pronoun is used to distinguish the neonate from his mother.

This chapter considers many anatomical, physiological and biochemical adaptations that characterise the transition of a term fetus to an independent neonate (birth to 28 days). Throughout intrauterine life, fetal survival is dependent on the mother; however, at birth anatomical, physiological and biochemical changes contribute to independent extrauterine life. Every system contributes to the ever-changing homeostatic conditions crucial to independence. The respiratory and cardiovascular systems are amongst the first to respond and initiate changes leading to a considerable rise in the neonate’s blood partial pressure of carbon dioxide (Pco 2). This initiates the respiratory drive that enables the neonate to take the first breath and maintain effective respiration. Blood oxygen content increases and favourable haemodynamic changes support and adjust cardiovascular and respiratory functions, impacting on oxygen perfusion of every organ and system. Oxygen supports cell metabolism and the production of energy whilst metabolic waste, including water, urea, salts and acids, is efficiently eliminated. It is important that health care practitioners caring for mothers and their neonates understand the complex changes that occur at this stage of life.

The appearance of the normal neonate

General appearance and the skin and hair at birth

At 40 weeks gestation the neonate (Fig. 48.1) weighs about 3500–4000 g and averages 50–55 cm in length. His occipitofrontal head circumference averages 35 cm making his head almost 25% of total body mass; the brain weighs between 300 and 400 g (Collins 2004). A healthy neonate appears plump with a rounded abdomen, largely due to deposition of subcutaneous fat and water. At birth the upper and lower limbs are of a similar length although primary ossification is present only in the upper limbs. Term neonates cannot achieve full elbow extension but flexion up to 145° is possible. They have a strong palmar grasp within a few days of birth. All four limbs should have five separated digits with well-formed nails and well-defined palmar and sole features.

|

| Figure 48.1 Skin-to-skin contact in a warm labour ward. (Courtesy of Professor J Hedgecoe.) |

Fine but dishevelled, silky hair covers the scalp. Some neonates appear fairly bald but others have luxuriant straight or curly hair. Abnormally unruly hair on the forehead or the back of the head and neck, especially when accompanied by unusual facies, may imply underlying genetic or chromosomal problems (Avery et al 1999). Remnants of lanugo, the fine hair that covers the entire body during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, may be present on the shoulders, the forehead, in the axilla, the groins and other parts of the body, especially if the neonate is premature. The degree of skin pigmentation is determined by the neonate’s gestation as well as the race of his natural parents.

In healthy neonates the skin, mucous membranes and nails should be a good colour, indicating favourable tissue perfusion and oxygenation. Generally, pigmentation of the nipples and genitalia is deeper in neonates with darker skin complexions. A linea nigra may be present in the lower abdominal midline and, depending on racial origin, diffuse bluish-black skin colouration known as the Mongolian blue spot may be present, usually over the sacrum.

Humans are unique amongst primates in having large sebaceous glands which produce sebum over the scalp, face and upper back. These glands are very active in utero, producing waxy substances that mix with dead skin cells and form vernix caseosa, which initially covers the entire fetal skin. Term neonates only show residual vernix caseosa being present in the groins, the axillae and sometimes the scalp. A few distended sebaceous glands called milia may present over the nose, forehead and chin.

Eccrine glands (sweat glands) first appear in fetuses at 5 months of gestation on the palms and the soles of its feet. At the same time, apocrine glands (scent glands), used by many mammals for cooling, develop throughout the body. By 7 months the apocrine glands disappear except for in the armpits, pubic area, around the nipples and lips while the eccrine glands continue to spread all over the body. In humans, but no other primates, these glands are used for sweat cooling when the body temperature rises above a critical physiological point (Carlton 2003). Although the eccrine glands are inactive for the first few days of life most neonates experience a regional eccrine gland maturation in the craniocaudal direction, with the earliest perspiration occurring on the forehead followed by the chest, upper arms and then the rest of the body (Collins 2004).

Posture and crying

After birth most neonates lie in a flexed position emulating the fetal position and resisting limb extension. Once their arms are extended, neonates show a tendency, possibly by reflex, to move both arms outwards. When placed on their back, there is a distinctive tendency to turn their heads spontaneously to one side, usually the right side, elevating the left shoulder. Conversely, when placed in the prone position neonates tend to draw their knees under their abdomen, elevating their buttocks and turning their head to one side. At term, healthy neonates are active and should move all four limbs spontaneously. These postural phenomena may not be evident in premature neonates due to the structural immaturity of the neural and locomotor systems. Neonates that hold their arm(s) alongside the body in internal rotation may be manifesting Erb–Duchenne paralysis which is caused by damage to the upper root of the brachial plexus involving the 5th and 6th cranial roots.

Crying is a physiological response to hunger, discomfort and distress and serves to alert the mother. The duration and type of crying vary with the severity of the distress (see Ch. 57) and attentive mothers quickly learn to discern between the different types of crying. Overby (2003) suggests that a 2-week-old neonate may cry intermittently on average 2 h per day, increasing these episodes to a total of 3 h per day by 6 weeks of age. From then on most healthy babies are physically more comfortable, more secure, and crying reduces to about 1 h per day.

Eyes

Competent examination of a neonate’s eyes requires knowledge, skills and patience. The external appearance of the eyes can reflect racial origins as seen in Oriental neonates. Neonates born with Down syndrome also have epicanthic folds (vertical pleats of skin that overlap the medial angles of the eyes), although epicanthic folds are common in other neonates, especially those of Asian origin. It is important to establish the structural features of the eyes and gentle attempts should be made to establish their presence, position, relative size and shape. Gross structural anomalies should be ruled out, and if present must be proactively treated. The colour of the neonate’s eyes may be attributed to the poorly defined iris generally appearing dark blue-grey, although some dark-skinned neonates tend to have brown eyes at birth. Permanent colouring of the iris may take several years to develop.

Assessing a neonate’s vision by an observed reaction to light is adequate unless significant structural anomalies warrant a fuller assessment. This requires a relatively dark room and a moderately bright beam of light in order to avoid stimulating reflex eye closure. The pupil size of term neonates should be equal, average in diameter within a range of 1.8 mm (when constricted) and 5.4 mm (when dilated). Measurements that fall outside these parameters should be further investigated, especially if a space-occupying lesion is suspected. Assessment of vision is best achieved when the neonate is content but alert, although neonates startle in response to a bright light even if their eyelids are closed, indicating that the optic pathways are functioning (Avery et al 1999).

Neonates cannot generally produce tears, which provide a natural lubricant and antiseptic for the eyes. This contributes to a higher incidence of eye infections such as conjunctivitis, often further complicated by temporary blockage of the lacrimal ducts, which under normal conditions help to keep the conjunctiva moist and clean. Avery et al (1999) advocate that any symptoms of tearing or persistent discharge from the eyes appearing after the 2nd day after birth should be investigated to exclude unsuspected lesions, abrasions, glaucoma and congenital or acquired infection.

Ears

A considerable range of factors, including the amounts of cartilage and activity of the auricular muscles, determine the shape, position and resistance to deformation of the external ears. Both ears should be placed symmetrically on either side of head. The position of the ear lobes generally approximates with the vertical distance from the arch of the brow to the lower parts of the nose (Avery et al 1999). Preauricular pits and skin appendages are fairly common (Carlton 2003) but more significant malformations, low-set ears and other dysmorphic features tend to be associated with urogenital malformations, deafness and autosomal dominant problems. Alert neonates with normal auditory capability generally react to a ringing bell, are startled or cry in response to sudden, unaccustomed loud noise and turn spontaneously towards human speech. The absence of such behaviours requires more systematic audiometry assessments.

Nose

Most neonates are obligate nose-breathers and their respiratory function depends on the patency of both nares. Nasal deformities and nasolacrimal duct obstructions should be ruled out. Although unilateral or bilateral anatomical obstructions caused by choanal atresia are rare these must be ruled out, especially in neonates who develop respiratory difficulties and cyanosis soon after birth.

Mouth and throat

The shape of the mouth and oral cavity is partly determined by neuromotor activity that occurs during fetal life. The tongue, buccal surfaces, palate, uvula and posterior aspects of the oral cavity should be inspected visually but the gum and hard palate are best examined by gentle finger palpation. Healthy neonates should have a gag reflex and usually suckle vigorously on a finger. In some neonates the tongue may be attached to a short central frenulum but this anomaly rarely interferes with feeding or later speech development. The presence of facial asymmetries on feeding or crying may suggest facial nerve paresis.

Neck and chest

Mature neonates have a full range of spontaneous neck movements although the neck is short and the muscles are incapable of supporting the weight of the head. The absence of, or abnormalities in, spontaneous movements may indicate cervical spine abnormalities or the presence of space-occupying lesions such as goitre or cystic hygromas which may compress and distort the central position of the trachea causing inspiratory obstruction. Neck trauma occurring at birth where the cervical nerves are damaged may lead to the neonate developing Horner’s syndrome. In instances where the phrenic nerve(s) is damaged the neonate will develop corresponding paralysis of the diaphragm with respiratory difficulties. The chest at term should be symmetrical, barrel-shaped with a prominent xiphoid sternum and compliant ribs. The chest circumference is generally 1–2 cm less than the head circumference. The neonate’s lung sounds are more tubular than vesicular due to better sound transmission from the large airways across the small chest.

Major systemic characteristics of the neonate

The haematological system

Circulatory volume

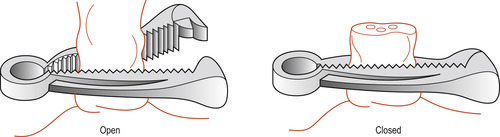

The separation of the fetus from the placental circulation following birth is a major physiological event. The umbilical arteries taking deoxygenated blood from fetus to placenta for oxygenation constrict whilst the umbilical vein remains dilated limiting fetal blood loss. Fetal–placental blood volume varies from 110 to 120 ml/kg (Padbury 2003) throughout the latter parts of pregnancy, although approximately 80 ml/kg of this blood is probably in the neonate. At delivery, if the umbilical cord is cut immediately or there is low intrauterine pressure or the neonate is held above the uterus, placental transfusion does not occur. However, Padbury (2003) suggests that within 5–15 s of delivery 5–15 ml/kg of placental blood may be transfused with the uterine contraction that initiates the 3rd stage of labour. If umbilical cord clamping is delayed for 60–90 s or the neonate is held below the uterus, more than 25–30 ml/kg of placental blood is transfused to the neonate. Conversely, neonates held more than 50 cm above the introitus may receive negligible amounts of placental blood and it is conceivable that small amounts of neonatal blood could transfuse into the placenta. Clamping of the umbilical cord, which stops all blood flow (Fig. 48.2) is an important haemodynamic step for the neonate.

|

| Figure 48.2 A cord clamp. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

Early versus late clamping of the umbilical cord

There are associated advantages and disadvantages. In general the umbilical cord is clamped early to avert systemic difficulties especially seen in premature neonates whose cardiovascular and respiratory systems are less well equipped to deal with additional volumes, high erythrocyte values and subsequent hyperbilirubinaemia. As any increase in plasma volume expands the vascular compartment, especially in the immature lungs, transfusion of 80 ml of placental blood may pose a significant risk to the neonate.

Controversially, some evidence suggests that late clamping of the umbilical cord (30 s following birth) may be beneficial in some premature neonates. The ensuing increase in circulating blood volume may improve cardiac output, enhance oxygen transportation, support renal perfusion and maintain acid–base balance. However, such practices should generally be avoided in neonates who are born with a history of hydrops fetalis or rhesus isoimmunisation (see Ch. 52) and those at risk of developing polycythaemia because of cyanotic heart disease (see Ch. 51). Caution should also be exercised in neonates born with severe systemic immaturity caused by maternal diabetes mellitus (see Ch. 50). Finally, in multiple births, the cord of the first-born neonate should be clamped early to prevent blood loss from the unborn fetus to the newborn sibling through any communicating placental circulation.

Adaptations in the neonate’s haematological parameters

Circulating blood volume at term averages 85–90 ml/kg of body weight (Padbury 2003). Haemopoiesis proceeds at a relatively steady pace ensuring that all cell types remain in circulation within narrow limits. Haemopoiesis is highly responsive, with a unique capacity to up-regulate or down-regulate the production of any cell type on demand. This responsiveness is also crucial in ensuring that the transition in the composition of the neonate’s blood is successful. Changes continue to occur during the transitional period of the 1st week of life when the type and quantities of haemoglobin change, with fetal haemoglobin being gradually replaced by adult haemoglobin more suited to extrauterine life.

The complex microanatomical and physiological processes that regulate haemopoiesis lead to equilibrium between cell production, maturation, function and biodegradation. The neonate’s blood cells gradually change from their fetal state to that of the child in whom mature erythrocytes function for 120 days, platelets for 10 days and neutrophils for 6–8 h. Genetic, epigenetic and a range of physiological variables influence the differentiation of the red bone marrow’s pleuripotent stem cells into mature blood (Pocock & Richards 2006). These include haemopoietic growth factors, such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor ( G-CSF), granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor ( GM-CSF), interleukin 6 (IL-6) and interleukin 8 (IL-8). For example, GM-CSF stimulates myeloid progenitor cell cycling, clonal development of neutrophils and enhances neutrophil function as phagocytic cells (see Ch. 29).

The erythrocyte count at birth averages 5.3 × 10 −6, generating a mean packed cell volume of 56% and a haemoglobin of 18.5 g/dl (Avery et al 1999). As many of these erythrocytes are nucleate or contain fetal haemoglobin they are fairly rapidly biodegraded by the reticuloendothelial system and it is unusual to find nucleated erythrocytes in circulation after the first week of extrauterine life. The earliest erythrocytes are normoblasts, which differentiate into reticulocytes and subsequently mature into erythrocytes containing predominantly adult haemoglobin (HbA).

The maturation of precursor cells into competent erythrocytes is controlled by a vast range of factors including erythropoietin, which is produced in the liver during fetal life and the kidneys after birth. Erythropoietin binds to specific receptor sites found in the membrane of myelocytic cells and erythroblasts, accelerating their differentiation and maturation respectively, by mechanisms that are not fully understood (Pocock & Richards 2006). Normal erythropoiesis also depends on the presence of iron, vitamin C and the vitamin B group.

The relative increase in erythrocytes due to plasma reduction and haemoconcentration which occurs in the first few hours/days of life is a transitional phenomenon, corrected by the rapid destruction of excess erythrocytes which occurs following birth. A more physiological erythrocyte count is achieved by 6 months (Pearson 2003). Nucleated, immature erythrocytes are seen in large numbers during the first 24 h following birth, possibly due to stressors associated with birth, but these usually disappear within 4 days. Significantly, the fetal blood erythropoietin values observed during intrauterine life fall within the first 24 h, but gradually return to physiological values during the first 2–3 months after birth. This coincides with the steady resumption of erythropoiesis. Erythrocytes are more specialised in composition than most other cells because of the presence of haemoglobin, which accounts for 95% of total cellular protein content.

Cord blood haemoglobin content varies with gestational age but broad parameters are suggested by Avery et al (1999). In healthy mature neonates haemoglobin averages 16.5–18.5 g/dl. This may increase by a further 6 g/dl over the first 24 h due to a shift in fluid distribution, associated diuresis, reduction in circulating blood volume and haemoconcentration. There is a gradual reduction in haemoglobin (HbF) concentration back to umbilical cord blood values by the end of the 1st week of life. By 3 months, the haemoglobin level in healthy infants tends to fall to 12 g/dl (Pearson 2003) which contrasts sharply with the varied cord blood haemoglobin content shown in the following résumé:

• Fetal haemoglobin (HbF): 50–85%.

• Adult haemoglobin (HbA): 15–40%.

• Haemoglobin A 2 (HbA 2): <2%.

As new erythrocytes are produced the rate of HbF production is reduced and the rate of HbA production increases so that at 4 months of age the average healthy child has less than 20% of HbF.

A primary function of haemoglobin is to combine reversibly with oxygen and carbon dioxide, thereby allowing the delivery of oxygen from the lungs to the tissues to support cellular metabolism. This function is best demonstrated by the oxygen dissociation curve, whereby the oxygen saturation of the blood is plotted against oxygen tension or partial pressure of the whole blood (Pocock & Richards 2006). Due to the high concentration of HbF in healthy neonates, the oxygen dissociation curve is placed firmly to the left, denoting high affinity of HbF for oxygen. This phenomenon is necessary for efficient extraction of oxygen from the maternal circulation during fetal life; however, after birth, HbF whilst capable of extracting large quantities of oxygen in the lungs releases oxygen to the tissues only as needed.

Affinity of HbF and HbA to oxygen is influenced by pH, Pco 2, 2,3-diphosphoglycerate (2,3-DPG) and blood temperature. After birth the shift in the oxygen dissociation curve to the right is partly attributable to organic phosphates which decrease the affinity of HbA to oxygen by competing for the same binding sites.

2,3-DPG is formed during anaerobic glycolysis (mature erythrocytes lack mitochondria and their glucose metabolism is anaerobic) and enhances the release of oxygen from haemoglobin. HbF has a lower affinity for 2,3-DPG than HbA and is able to bind oxygen more tenaciously. This accounts for the shift of the oxygen dissociation curve to the left in the fetus and neonate. Finally, the postnatal shift of the oxygen dissociation curve to the right is directly attributable to the gradual replacement of HbF by HbA which has a lower affinity for oxygen and greater capacity for oxygen to dissociate, thus enhancing oxygen release to the tissues (Marieb 2008).

White blood cells (WBCs) defend the body against genetically different antigens (see Ch. 29). At birth most neonates show an initial increase in the number of circulating white blood cells, possibly due to their displacement from other sites provoked by the stress of birth. However, gradual reduction in these cells brings about normal WBC values by the 5th day after birth. The two main functions of WBCs are phagocytosis and competent immune response (see Ch 29). In neonates neutrophils make up approximately 50% and lymphocytes about 30% of the total WBCs. However, the proportion of lymphocytes increases rapidly within the first few months to an average of 60%, and this value persists for the first 2 years of life. Monocytes are the most abundant cells in the first few weeks of extrauterine life but gradually decline to the much lower adult value.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree