Patient Story

A 57-year-old woman presented with red and scaling skin on both arms (Figure 166-1) with a request for a prescription for 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). The patient had blue eyes and white hair and was found to have 2 basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) on her face and shoulder. The patient stated that 5-FU had helped her arms in the past, but that the scaly lesions had returned. She avoids sun exposure now, but acknowledges receiving too much sun exposure while growing up. Another course of 5-FU was prescribed for her arms to prevent new skin cancers from forming.

Introduction

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are precursors on the continuum of carcinogenesis toward squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). However, each AK has a low risk of progression to malignancy and a high probability of spontaneous regression.1 Bowen disease (BD) is SCC in situ confined to the epidermis.

Synonyms

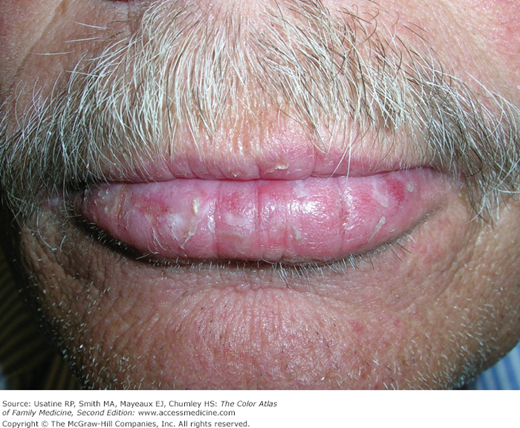

AK is also known as solar keratosis. AK on the lips is known as actinic cheilitis (Figure 166-2). BD is also known as SCC in situ of the skin. SCC in situ involving the penis is known as erythroplasia of Queyrat (Figure 166-3).

Epidemiology

- AKs and BD are seen frequently in light-skinned individuals who have had significant sun exposure.

- The prevalence of AK is estimated at 11% to 25% in adults older than age 40 years in the northern hemisphere, and increases with age.1 AKs are so common that they account for more than 10% of visits to dermatologists.

- The prevalence of BD is unknown.1

Etiology and Pathophysiology

UV rays induce mutation of the tumor-suppressor gene P53. Subsequent proliferation of mutated atypical epidermal keratinocytes give rise to the clinical lesion of AK.2 Multiple clinical and subclinical lesions may exist in an area of sun-damaged skin, a concept known as “field cancerization.”

AKs have the potential to become SCCs. The rate of malignant transformation has been variably estimated, but is probably no greater than 6% per AK over a 10-year period.3

In a large prospective cohort study, the risk of progression of AK to primary SCC (invasive or in situ) was 0.60% at 1 year and 2.57% at 4 years. Approximately 65% of all primary SCCs and 36% of all primary BCCs diagnosed in the study arose in lesions that previously were diagnosed clinically as AKs. Many AKs did resolve spontaneously, 55% AKs that were followed clinically were not present at 1 year and the 70% were not present at the 5-year follow-up.4

Risk Factors

- Total lifetime dose of UV radiation (natural sunlight, UV from tanning beds and radiation).1

- Fair skin.1

- Site-specific risk factors include tobacco for actinic cheilitis and human papilloma virus for genital and anal lesions.1

- Exposure to immunosuppressive drugs, especially organ transplant recipients.

- Personal or family history of skin cancers.

Diagnosis

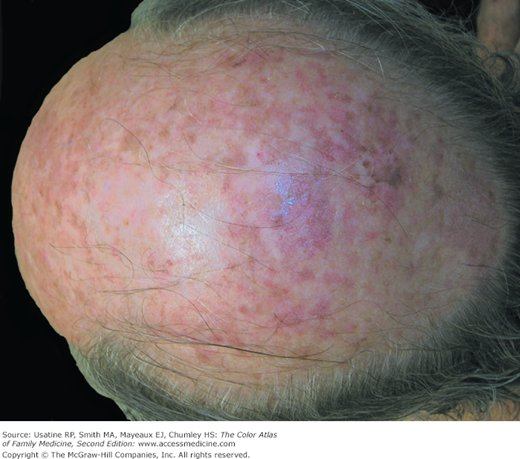

AKs are rough scaly spots seen on sun-exposed areas (Figure 166-1, 166-2, 166-3, 166-4, 166-5, and 166-6). They may be found by touch, as well as close visual inspection of the patient’s skin. BD appears similar to an AK, but tends to be larger in size and thicker with a well-demarcated border (Figure 166-7 and 166-8).

Both lesions are seen in areas with greatest sun exposure such as the face, forearms, dorsum of hands, lower legs of women, and the balding scalp (Figure 166-5) and tops of the ears in men.

AKs that appear premalignant may be diagnosed by observation only and treated with destructive methods (e.g., excision, electrosurgery, or cryosurgery) without biopsy. BD requires a biopsy for diagnosis. BD or SCC should be biopsied prior to treatment. A shave biopsy should produce enough tissue for histopathology.