6 1. Definition: A hernia is an abnormal protrusion of a viscus (Latin: internal organ) through its containing wall. Abdominal wall hernias are very common, especially in the groin (inguinal hernias) and umbilical area. 3. Indications to treat: Most hernias are operated on to ensure they do not enlarge, become uncomfortable, and to avoid the risk of strangulation. Reserve non-operative management for asymptomatic direct inguinal hernias, particularly in elderly, inactive or terminally ill patients and those who will not consent. The few who do not have an operation are best left without a truss, which is uncomfortable and difficult to manage. 4. Repair: There are three steps to a hernia repair: 5. Select the approach (open or laparoscopic): This depends on the hernia site, your surgical expertise, operating facilities, the patient’s anatomy and wishes. Laparoscopic repair requires different surgical skills, may be more expensive for the hospital than an open repair and cannot be undertaken under local anaesthetic. 6. Consent: Ensure the patient has given full consent to the operation and understands the circumstances under which it will be performed. Provide full information on discharge arrangements. 7. Suture the repair with a non-absorbable monofilament suture on a curved, round-bodied needle, polyamide (nylon) and polypropylene being the most popular. Remember the following: 8. Prosthetic mesh in hernia repair: If you use prosthetic mesh for the repair, give a prophylactic dose of antibiotic at induction. Always administer this in operations for strangulated hernia as the wound may be contaminated. 9. Local anaesthesia is suitable for many groin hernia repairs and some other hernias. Young adults may not tolerate it alone and may require the addition of sedation. There are economic benefits, particularly for day-case surgery and in the elderly. Its use carries its own risks and the following general considerations apply: 10. Close the skin with sutures, clips, staples or adhesive strips. Continuous, absorbable subcuticular stitches provide a very neat result and avoid the discomfort and cost of suture removal. 11. Provide adequate postoperative analgesia. Inject local anaesthetic into the wound. Prescribe preoperative analgesics such as IV paracetamol and regular postoperative oral medication such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatories or co-codamol for 2 days. 13. Hernia recurrence is related to technical failure, including a missed hernial sac and inadequate placement or sizing of the mesh. 1. Most inguinal hernias are repaired. 2. Repair techniques: There are several open and laparoscopic techniques described to repair an inguinal hernia: 3. Selecting the correct approach to repair an inguinal hernia. 1. The diagnosis of groin swellings is notoriously difficult. Experienced as well as inexperienced surgeons make frequent mistakes. Do not accept the diagnosis of the referring doctor, but take a fresh history and carry out a complete examination. Is there another possible cause for the patient’s symptoms apart from the hernia? If a clear history of a reducible intermittent lump in the groin is accompanied by a negative examination, a hernia will be found on exploration; if in doubt, consider herniography. 2. Palpation is not the only or even the most important method of examination. Look with the patient standing and again with the patient supine. If you see a lump, ask yourself ‘Where is it?’ If it is reducible, where does it first reappear on coughing or straining? A cough impulse may be absent, especially over a femoral hernia in which a small sac is covered by much fatty extra-peritoneal tissue. Conversely, a cough impulse is present over Malgaigne’s (Parisian surgeon 1806–1856) bulging, or a saphena varix. 3. Always examine the scrotum and its contents in male patients. If there is a swelling, ask yourself the fundamental question ‘Can I get above it?’ Occasionally you discover undescended testes; deal with them at the same procedure. 1. Obtain the patient’s signed consent, warning of the possible complications of haematoma (especially for large inguinoscrotal hernias), ischaemic orchitis, persistent groin pain, hernia recurrence, wound and mesh infection, and damage to local structures, which can be more significant with a laparoscopic approach. In laparoscopic surgery obtain consent for conversion to open repair if necessary. Discuss with the patient what action you should take, if, at operation for unilateral hernia, an unexpected, asymptomatic contralateral hernia is revealed. Record the agreed consent on the form. 1. Follow the instructions for local anaesthesia. 2. Inject 20 ml along the line of the proposed incision using a fine needle to raise a continuous bleb within the epidermis. 3. Replace the needle with a larger one to inject deeply and along the same line superficial to the anterior wall of the canal. 4. Blunt the needle to improve the ‘feel’ of passage through the aponeurosis and inject 5 ml of fluid 2 cm above and medial to the anterior superior iliac spine deep to the external oblique to block the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves. 5. Reserve about half the volume of anaesthetic to inject under the external oblique aponeurosis, around the neck of the sac and into other sensitive areas during the operation. 1. Start the incision a finger’s breadth above the palpable pubic tubercle within the skin crease which is often present (as opposed to parallel to the inguinal ligament) and extend this to two-thirds of the way to the anterior superior iliac spine. Incise the fascia to expose the external oblique aponeurosis, ligating and dividing two or three large veins that cross the line of the incision. Avoid cutting into the hernial sac and spermatic cord at the medial end of the incision. 2. Expose the glistening fibres of the external oblique aponeurosis and identify the external inguinal ring, which confirms the line of the inguinal canal. 3. With a scalpel split the external oblique aponeurosis in the line of the fibres. Enlarge the split medially and laterally by pushing the half-closed blades of the scissors in the line of the fibres. At the medial end of the split you open the external inguinal ring. Ensure that you do so. Do not allow curved blades of scissors to skirt around the crura of the ring. Preserve the ilioinguinal nerve, lying under the external oblique, to minimize the risk of postoperative numbness and pain. 4. Apply artery forceps to the edges of the aponeurosis and gently elevate each side. As you evert the upper leaf, look for the arching lower border of internal oblique muscle, with the cord below it. As you evert the lower leaf, sweep loose tissue from the deep surface of the inguinal ligament. 1. Start to mobilize the cord by incising, just above and lateral to the public tubercle, the ‘mesentery’ of fascia and fibres of cremasteric muscle that extends downwards from the medial part of the conjoint tendon to envelop the cord. Deepen this small incision behind the cord, drawing the latter downwards while passing the index finger from below against the pubic tubercle, to develop a plane to encircle the cord and apply a hernia ring. 2. Now dislocate the cord laterally and downwards by incising the coverings along lines just above and below it. This exposes a direct hernia, which can be freed from the cord. 3. Carefully divide the fibres of cremaster just distal to the internal ring, ensuring haemostasis. 4. Even though a direct hernia is evident, examine the cord. Normally it is about the thickness of a pencil. It is markedly distended by an unreduced, sometimes adherent or sliding, hernia. A thickened sac results from a longstanding indirect hernia. Cord lipomata produce thickening, as does an encysted hydrocele of the cord (in females a hydrocele of the canal of Nuck). To exclude an indirect sac, open the spermatic fascia covering the cord and identify the edge of the peritoneum deep to the internal ring. 5. Identify the lower arching fibres of the internal oblique muscle, becoming tendinous at the conjoint tendon, and examine the posterior wall below this. A direct hernia may be a large bulge, a diffuse weakness of the whole posterior wall or, less often, a funicular hernia through a small localized defect (Ogilvie’s hernia). 6. If you have any concern that a femoral hernia may be present, incise the transversalis fascia to expose the upper aspect of the femoral canal. If a femoral sac is present, deal with it via a High approach repair (Lothiesen procedure, see later). 7. The cremasteric vessels pass medially from the inferior epigastric vessels adjacent to the cord. If the internal ring is enlarged it may be necessary to carefully identify, isolate, ligate and then divide the cremasteric vessels to facilitate a snug repair at the internal ring. If they are injured more medially, ligate them proximally and distally to the damage. 1. With the left thumb in front, gently stretch the previously mobilized cord over the left index finger, which is placed behind the cord. Make a short split with a knife, in the line of the cord, through the cremasteric and internal spermatic fascial layers. Continue the split proximally to the internal ring using scissors, first with their blades on the flat, separating fascia from deeper layers, then splitting the fascia. 2. Look for the sac. A white curved edge may be seen if the hernial sac is small (Fig. 6.1); if it is large it will be obvious as the fascial layers are separated. Using the point of the scalpel, gently incise the fibres crossing the fundus or the side edges of the sac. Unless it is very adherent it will then be possible to peel the sac out of the cord with the aid of a few further strokes of the blade. The sac is then dissected back to the level of the abdominal peritoneum, using a combination of wiping with a gauze swab and snipping firm attachments with scissors. Keep the dissection close to the sac and avoid damaging other structures in the cord. 3. Pick up the sac with two artery forceps and open it between the forceps with a scissors. Note any contents of the sac and return them to the peritoneal cavity. Adherent omentum may be freed, or ligated and excised. Be sure this is not part of a sliding hernia (see below). 4. While the empty sac is held vertically by means of the artery forceps, transfix its neck with a polyglactin (Vicryl) suture. Tie the ends of the suture-ligature into a half hitch, completely encircle the neck of the sac and tie a triple-throw knot to ligate the neck of the sac. If contents tend to bulge into the sac, gently hold them back using non-toothed dissecting forceps, sliding them out as the ligature is tightened. 5. Do not let your assistant cut the ends of the ligature. First excise the sac 1 cm distal to the ligature. Examine the cut end to ensure that only sac is seen, it does not bleed and the suture is secure, then cut the ligature yourself. The stump of the sac should retract through the internal ring. 6. Alternatively, fully mobilize and simply invert the sac. It need not be ligated for this. 7. If the margins of the internal ring have been stretched by the indirect hernia, narrow the gap in the posterior wall using a non-absorbable suture to approximate the attenuated margins of the transversalis fascia medial to the cord. 8. If there are large extra-peritoneal lipomata, carefully isolate, ligate and excise them but do not try to dissect out all the fatty tissue. 1. Complete hernias, or scrotal funicular hernias, have no distal edge to the sac as seen at the level of the pubic tubercle. Attempts to dissect out the whole sac cause the scrotal part of the sac and the testis to be drawn into the wound, increasing the risk of haematoma or ischaemic orchitis. 2. Purposefully divide the sac straight across within the inguinal canal. Isolate the proximal portion up to the internal ring, and leave the distal portion open. In this way the dissection is kept to a minimum. 3. If the sac is adherent, open it in front and place artery forceps at intervals round the inside as markers. Lift up two forceps, stretch the portion of sac between them, separate the sac from the cord and cut it distal to the forceps. Take the next two forceps and repeat the manoeuvre. Continue in this manner until the proximal circumference of the sac is completely sectioned, with the edges still held in the forceps. 4. After stripping the proximal part of the sac to the inguinal ring, transfix and ligate the neck. 1. In some hernias, retroperitoneal structures slide down to form part of the sac wall, chiefly the sigmoid colon, bladder or caecum. Always be on the look-out for sliding hernia. 2. You discover the sliding component when you attempt to empty and free the sac. 3. If the sac is intact, do not open it. If the sac has been opened, mark the fringe of peritoneum on the viscus with artery forceps and close the sac. Ensure that closure is complete. 4. Make sure that neither the organ nor its blood supply was damaged before the true situation was recognized. If the bladder was damaged, repair the wall and remember to insert an indwelling urethral catheter at the end of the operation. 5. Fully mobilize the entire hernia sac and sliding viscus from the cord and replace it in the abdomen. If the sac is inguinoscrotal, divide and close it below the sliding viscus and return it to the abdomen. 1. Always look for an indirect sac. 2. If the direct sac is funicular, resulting from a localized defect in the posterior wall, isolate it, empty it, then transfix, ligate and divide it at the neck. Define the margins of the posterior wall defect. If the hole is small and it can be closed without tension, suture it now, with non-absorbable material on a fine, curved, round-bodied needle. 3. More often the sac is diffuse and associated with a general weakness of the posterior wall. Do not open it. Push it inwards and maintain the invagination with a running suture of absorbable or non-absorbable suture, carried across the stretched transversalis fascia so as to flatten the bulge without tension. The sutures must not bite deeply or the bowel or bladder may be damaged. 1. The mesh should have overall dimensions of 11 cm × 6 cm. To accommodate this, separate the external oblique aponeurosis from the deeper layers superiorly and medially and from the muscular part of internal oblique laterally to create an adequate pocket to receive the mesh. 2. Prepare the polypropylene mesh as indicated in Figure 6.2A. The lower medial corner is slightly rounded, the upper medial corner rather more so. The mesh is then incised from its lateral margin, placing the cut one-third of the distance from the lower edge. The cut extends for approximately half the length of the mesh, depending upon the size of the patient; it may need to be extended when the mesh is in place. In small patients the upper edge may need to be trimmed slightly. 3. Place the mesh in its final position (Fig. 6.2B). Lift the cord and bring the narrow lower tail through under it, below the internal ring. Then tuck the lateral end under the external oblique; the lower edge of the mesh now lies along the inguinal ligament. Now insert the upper two-thirds of the mesh so that it lies under the external oblique aponeurosis superiorly and medially, ensuring that there is a good overlap on the rectus sheath medially. Tuck the wide upper tail under the external oblique laterally, with its lower edge over the lower tail. Insert your fingers under external oblique superiorly and laterally to ensure that the mesh lies quite flat in the peripheral part of the pocket, though there may be a slight bulge centrally. 4. The mesh does need to be secured in place across the posterior wall of the inguinal canal. Although most use polypropylene sutures, it is possible to use staples or glue. Start the fixation by passing a 2/0 polypropylene stitch through the mesh and the tissues overlying the pubic tubercle and tying this. Use this to form a continuous locking suture between the lower edge of the mesh and the inguinal ligament, working from medial to lateral, extending to at least 2 cm lateral to the internal ring. Take irregular bites of the inguinal ligament to avoid splitting it and do not allow the lower leaf of the external oblique to roll in and be included in the sutures; if this happens, there will be no external oblique left to close. For the medial part of this suture line it is best to retract the cord downwards. Then, as the suture approaches the internal ring, move the cord cephalad and pass the needle under it to continue laterally. When suturing immediately in front of the femoral vessels be careful to take only the ligament and not a bite of a major vessel! 5. If the slit in the mesh is too short extend it so that the cord passes directly from the internal ring to the opening in the mesh. A bulky cord may be accommodated by making a small cut in the mesh at right-angles to the slit. If you made too long a cut, all is not lost; simply shorten the slit with one or two sutures. 6. Overlap the tails of the mesh by bringing the lower edge of the upper portion in front of the lower tail and securing it to the inguinal ligament with two interrupted sutures (or by including it in the lateral part of the continuous suture). The resulting opening in the mesh should be a snug, but not a tight, fit around the cord (Fig. 6.2B). 7. Now secure the medial and upper margins of the mesh with about six interrupted sutures, avoiding the nerves (Fig. 6.2B). These are most conveniently placed 0.5 cm away from the edge, so that the mesh lies flat on the underlying aponeurosis or muscle. The medial sutures are particularly important as there is less overlapping of the mesh there, making it a potential site for recurrence. 8. The mesh repair is now completed. It appears slightly redundant centrally but that does not matter. 9. Replace the cord in the inguinal canal. 10. Wash the inguinal canal with any remaining local anaesthetic, making sure not to remove it too quickly. 11. Close the external oblique aponeurosis with a synthetic absorbable suture, starting laterally and ending medially to reform the external ring snugly but not tightly around the emerging cord. Once again, take care to take bites at unequal distances from the edges; otherwise you will pull from the cut edges a strip of aponeurosis. 12. Appose the subcutaneous fascia with fine absorbable stitches and close the skin wound (see above). 1. Following repair of inguinal hernia under local anaesthesia, allow the patient to leave the operating theatre on foot. This is good for confidence. 2. Encourage patients to mobilize immediately after recovery from general anaesthesia. 3. Activities should be limited only by the patient’s comfort. 1. Scrotal complications: Ischaemic orchitis is an uncommon complication presenting as pain and swelling in the first few days after hernia repair. In a proportion of cases it results in testicular atrophy. Damage to the vas should be recognized and repaired at the time of hernia repair. Hydrocele formation is more common after transection of the sac and resorbs spontaneously in most cases. Genital oedema, relatively common in the first 3 days, settles spontaneously, requiring reassurance only. 2. Haematoma: Bruising can be significant, often involving the scrotum, to the alarm of the patient, developing a couple of days after surgery. Even significant haematomas can be left to resolve, although this may take months and does increase the risk of orchitis, mesh infection and possibly recurrence and groin pain. 3. Wound infections: Reddening of the wounds is not uncommon, but frank purulent discharge is. If this persists, be concerned about a mesh infection and consider removing the mesh. 4. Nerve injury: Some degree of transient numbness below and medial to the incision is very common and may persist with little disability. Of much more significance is the incidence of chronic residual pain that occurs in at least 3% of conventional hernia repairs. 5. Urinary problems: Make sure you are aware of the possibility of bladder injury and recognize it at the time of surgery. Treat it by primary repair and insert an indwelling catheter until a cystogram demonstrates healing. Postoperative urinary retention becomes more common with age, after general anaesthesia and following bilateral hernia repair and usually resolves following a 24-hour period of catheterization. 6. Impotence: This is an occasional complaint for which there does not appear to be an organic basis. 1. Consider laparoscopic repair to avoid the adherent tissues. 2. For open operations, take considerable time to define the anatomy. This is difficult as there is distortion from the previous repair and all structures tend to be encased in fibrous tissue. 3. Once the anatomy is defined, secure the posterior wall and undertake a mesh repair as described. 4. Orchidectomy need not be considered, but warn the patient of the increased risk of ischaemic orchitis. 1. Incise or excise the previous skin scar. 2. Deepen the incision at a higher or more lateral level than the previous approach, so that unscarred external oblique aponeurosis is encountered first. 3. Display the external oblique aponeurosis downwards to the inguinal ligament. 4. Re-open the inguinal canal through the scar in the external oblique aponeurosis. Avoid damaging the contents of the canal, which will be adherent. 5. Elevate the upper and lower leaves of the external oblique aponeurosis until you reach unscarred tissue. 6. Isolate the spermatic cord below the pubic tubercle and follow it up to the internal ring. It may lie in an unusual place or be adherent and the vas may have been separated from the vessels. 1. Look for an indirect recurrence. If you find a sac, isolate it, empty it, then transfix, ligate and divide it at the neck. 2. Look for a direct recurrence. If the recurrence is funicular, isolate it, empty it, then transfix, ligate and divide it at the neck. If it is a diffuse bulge, invert the sac with a running suture to maintain the invagination. 1. Almost always, the repair should be a mesh repair as outlined above. 2. Occasionally, for a small well defined direct defect, a ‘plug’ repair can be undertaken. Insert a bunched-up piece of polypropylene mesh through the small defect into the extra-peritoneal space and secure it with a few sutures across the open defect. 1. Most operations listed as strangulated hernia are carried out for painful, irreducible or obstructed hernias. 2. An open approach to the strangulated inguinal hernia repair is easiest and most common, 3. Strangulation results from venous obstruction, a rise in capillary hydrostatic pressure, transudation of fluid, exudation of protein and cells, and eventual arterial obstruction. Alternatively, the pressure of a sharp constriction ring at the neck of the sac may cause local necrosis of the bowel wall. 4. Once diagnosed, try to reduce the hernia, making emergency surgery unnecessary and allowing for an early elective operation. The effect of reassuring the patient, who is laid supine in the head-down position, encourages spontaneous reduction. Try to gently reduce the hernia, making sure not to hurt the patient. There is a slight but real risk that you may reduce the hernia en masse: that is, the hernia remains within the peritoneal sac, the neck of which remains as a constriction, so the strangulation is not relieved. Some hernias reduce spontaneously when the patient is sedated prior to operation, or when anaesthesia is induced. 1. Do not rush patients with strangulated hernias to the operating theatre. Make sure you know any reason (such as urinary outflow obstruction or a chest infection) why the patient has developed strangulation now. Identify coincidental disease that may make general anaesthesia and operation hazardous. 2. If strangulation has been present for some time, the patient requires fluid and electrolyte replacement. This takes priority over the operation. It is likely, in such cases, that bowel in the hernia will already be irreversibly ischaemic, so little is lost by the delay. 1. If the history was short, the sac will frequently be empty by the time you expose it. The relaxation produced by the anaesthetic often succeeds when other conservative methods have failed to reduce a hernia. There is then no merit in exploring the abdomen. Repair the hernia as though this were an elective operation. 2. If bowel is present in the sac, do not let it slip back into the abdomen but gently draw it down into view. The bowel is likely to have suffered the greatest damage where it was trapped at the neck of the sac. 3. Feel the margins of the neck of the sac with a fingertip. 4. In Richter’s hernia, a knuckle of the bowel wall is trapped. The bowel lumen is thus not obstructed but the knuckle may become gangrenous and perforate. 5. Maydl’s strangulation is very rare. Two loops lie in the sac but the blood supply to an intermediate loop within the abdomen may be prejudiced so that it is gangrenous. 1. If the neck of the hernia sac is constricted, first draw down healthy bowel, then place an index fingertip on each side of the contents, nails facing outwards. Gently dilate the neck of the sac (Fig. 6.3). Make sure the bowel does not slip back. Draw it out to ensure that there is no peritoneal constriction and to expose healthy bowel. 2. If the bowel is viable, return it to the abdomen. 3. If necessary, resect a gangrenous segment of bowel, performing an end-to-end anastomosis.

Abdominal wall and hernias

GENERAL ISSUES IN HERNIA SURGERY

Consider whether there is another cause for the patient’s symptoms. Groin pain may be due to osteoarthrosis of the hip or a groin strain, rather than the obvious inguinal hernia. Epigastric pain may be biliary colic or a symptom of peptic ulcer and not a consequence of the epigastric hernia.

Consider whether there is another cause for the patient’s symptoms. Groin pain may be due to osteoarthrosis of the hip or a groin strain, rather than the obvious inguinal hernia. Epigastric pain may be biliary colic or a symptom of peptic ulcer and not a consequence of the epigastric hernia.

The hernia may not be evident in the anaesthetized patient so mark the site (and side) preoperatively.

The hernia may not be evident in the anaesthetized patient so mark the site (and side) preoperatively.

Herniotomy: remove the hernia sac

Herniotomy: remove the hernia sac

Herniorraphy: close the hernia neck or wall defect

Herniorraphy: close the hernia neck or wall defect

Hernioplasty: support the defect, usually using a prosthetic mesh.

Hernioplasty: support the defect, usually using a prosthetic mesh.

Monofilament sutures require extra knots for security.

Monofilament sutures require extra knots for security.

Handle synthetic monofilament suture material with care. Do not hold it with instruments or jerk it when tying knots or it will be seriously weakened.

Handle synthetic monofilament suture material with care. Do not hold it with instruments or jerk it when tying knots or it will be seriously weakened.

Do not drag the fine suture through the tissues, since it will cut them, enlarging the holes.

Do not drag the fine suture through the tissues, since it will cut them, enlarging the holes.

Do not tie the sutures too tightly. They will either cut out now or strangulate the tissues and weaken them later and may also increase the risk of troublesome neuralgia.

Do not tie the sutures too tightly. They will either cut out now or strangulate the tissues and weaken them later and may also increase the risk of troublesome neuralgia.

Do not take even bites of the tissues. Although this looks neat, evenly inserted stitches tend to detach a strip of aponeurosis. Therefore, take successive bites at differing distances from the edge.

Do not take even bites of the tissues. Although this looks neat, evenly inserted stitches tend to detach a strip of aponeurosis. Therefore, take successive bites at differing distances from the edge.

Strength/stiffness results not only from the intrinsic strength of the mesh, often related to the density of prosthetic material, but also from the resulting in-growth of fibrosis, which is greater with smaller pore sizes.

Strength/stiffness results not only from the intrinsic strength of the mesh, often related to the density of prosthetic material, but also from the resulting in-growth of fibrosis, which is greater with smaller pore sizes.

Flexibility/elasticity: meshes should be flexible enough to conform to the abdominal wall movements on a long-term basis. It is increasingly apparent that current polypropylene meshes may be unnecessarily strong, resulting in pain and the sensation of stiffness when compared with lighter-weight open-weave or compound meshes (e.g. Vypro, Ethicon).

Flexibility/elasticity: meshes should be flexible enough to conform to the abdominal wall movements on a long-term basis. It is increasingly apparent that current polypropylene meshes may be unnecessarily strong, resulting in pain and the sensation of stiffness when compared with lighter-weight open-weave or compound meshes (e.g. Vypro, Ethicon).

Size and shape: all prostheses shrink as part of the process of scar maturation. Therefore allow a minimum overlap of the hernial defect by the mesh of 2–3 cm for initial fixation and long-term coverage. For laparoscopic ventral hernia repair, favour a 5-cm overlap. Various preformed meshes are now available for some hernia sites.

Size and shape: all prostheses shrink as part of the process of scar maturation. Therefore allow a minimum overlap of the hernial defect by the mesh of 2–3 cm for initial fixation and long-term coverage. For laparoscopic ventral hernia repair, favour a 5-cm overlap. Various preformed meshes are now available for some hernia sites.

Expense often limits the use of newer, composite meshes.

Expense often limits the use of newer, composite meshes.

Adhesion formation remains a problem, particularly with intraperitoneal implantation. Two-sided meshes, with one side engendering tissue ingrowth, the other inhibiting it (e.g. DualMesh, Gore, Proceed, Ethicon), reduce this risk.

Adhesion formation remains a problem, particularly with intraperitoneal implantation. Two-sided meshes, with one side engendering tissue ingrowth, the other inhibiting it (e.g. DualMesh, Gore, Proceed, Ethicon), reduce this risk.

Infection: systemic prophylactic antibiotics have been shown to reduce the risk of wound infection.

Infection: systemic prophylactic antibiotics have been shown to reduce the risk of wound infection.

Monitor the blood pressure, pulse rate and oxygen saturation.

Monitor the blood pressure, pulse rate and oxygen saturation.

Know the appropriate resuscitation procedures in case the patient develops an adverse reaction.

Know the appropriate resuscitation procedures in case the patient develops an adverse reaction.

For effective anaesthesia give a sufficient volume. Use either 0.5% lidocaine with adrenaline (epinephrine) 1 in 1000 000 or bupivacaine (0.25%). Select your choice of local anaesthetic for hernia operations and do not vary, to avoid confusion.

For effective anaesthesia give a sufficient volume. Use either 0.5% lidocaine with adrenaline (epinephrine) 1 in 1000 000 or bupivacaine (0.25%). Select your choice of local anaesthetic for hernia operations and do not vary, to avoid confusion.

Do not exceed the safe dose of local anaesthetic: for lidocaine with adrenaline (epinephrine) this is 70 mg lidocaine per kg, approximating for an average adult to 5000 mg, equivalent to 100 ml of a 0.5% solution.

Do not exceed the safe dose of local anaesthetic: for lidocaine with adrenaline (epinephrine) this is 70 mg lidocaine per kg, approximating for an average adult to 5000 mg, equivalent to 100 ml of a 0.5% solution.

Clearly record in the notes the dose of local anaesthetic and other drugs.

Clearly record in the notes the dose of local anaesthetic and other drugs.

Reduce bruising and haematoma formation by achieving meticulous haemostasis and judiciously inserting suction drains.

Reduce bruising and haematoma formation by achieving meticulous haemostasis and judiciously inserting suction drains.

Wound infection rarely requires more than drainage of any collection. Sinus formation is rare with the use of monofilament sutures but occasionally requires removal of suture knots or mesh.

Wound infection rarely requires more than drainage of any collection. Sinus formation is rare with the use of monofilament sutures but occasionally requires removal of suture knots or mesh.

INGUINAL HERNIA

Appraise

The Lichtenstein mesh repair, developed by Irving Lichtenstein (1920–2000) of Los Angeles, in 1984; in 1989 he reported no recurrences in 1000 patients after 1–5 years. It is the most popular open technique, relatively easy to master and has a low recurrence rate Other open techniques repair the posterior wall of the inguinal canal by suturing the conjoint tendon to the inguinal ligament (Bassini repair) or by overlapping the transversalis fascia (Shouldice repair).

The Lichtenstein mesh repair, developed by Irving Lichtenstein (1920–2000) of Los Angeles, in 1984; in 1989 he reported no recurrences in 1000 patients after 1–5 years. It is the most popular open technique, relatively easy to master and has a low recurrence rate Other open techniques repair the posterior wall of the inguinal canal by suturing the conjoint tendon to the inguinal ligament (Bassini repair) or by overlapping the transversalis fascia (Shouldice repair).

Through a laparoscopic approach a synthetic mesh can be placed in the pre-peritoneal space from the midline medially to a point close to the level of the anterior superior iliac spine laterally, thus covering the whole extent of the inguinal canal including the internal ring and the area medial to the inferior epigastric vessels where direct hernias originate, as well as covering the internal opening of the femoral canal. The pre-peritoneal space can be reached either via a total extra-peritoneal (TEP) approach which should not involve entry into the peritoneal cavity, or via a transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) approach. For inguinal hernia repairs the TEP requires more surgical experience, but is considered safer as the peritoneum is not breached.

Through a laparoscopic approach a synthetic mesh can be placed in the pre-peritoneal space from the midline medially to a point close to the level of the anterior superior iliac spine laterally, thus covering the whole extent of the inguinal canal including the internal ring and the area medial to the inferior epigastric vessels where direct hernias originate, as well as covering the internal opening of the femoral canal. The pre-peritoneal space can be reached either via a total extra-peritoneal (TEP) approach which should not involve entry into the peritoneal cavity, or via a transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) approach. For inguinal hernia repairs the TEP requires more surgical experience, but is considered safer as the peritoneum is not breached.

Familiarize yourself with all techniques and adapt them according to the patient’s anatomy and wishes, rather than be compromised by lack of surgical expertise or equipment. The two approaches (open and laparoscopic) require very different surgical skills.

Familiarize yourself with all techniques and adapt them according to the patient’s anatomy and wishes, rather than be compromised by lack of surgical expertise or equipment. The two approaches (open and laparoscopic) require very different surgical skills.

The laparoscopic approach has slightly less postoperative pain, a faster return to work, a lower incidence of chronic groin pain and fewer wound complications. Long-term recurrence rates are similar for both methods. Laparoscopic repair costs more and carries a very small risk of serious injury to the intestine or major blood vessels, especially if the TAPP approach is adopted.

The laparoscopic approach has slightly less postoperative pain, a faster return to work, a lower incidence of chronic groin pain and fewer wound complications. Long-term recurrence rates are similar for both methods. Laparoscopic repair costs more and carries a very small risk of serious injury to the intestine or major blood vessels, especially if the TAPP approach is adopted.

The open operation has the advantage of being feasible under local anaesthesia. It is also cheaper and simpler to learn, and is currently recommended by NICE as the procedure of choice for primary, unilateral inguinal hernia in the UK. Consider especially women with primary unilateral inguinal hernias for open surgery.

The open operation has the advantage of being feasible under local anaesthesia. It is also cheaper and simpler to learn, and is currently recommended by NICE as the procedure of choice for primary, unilateral inguinal hernia in the UK. Consider especially women with primary unilateral inguinal hernias for open surgery.

Repair a recurrent inguinal hernia through unscarred tissue: that is, if an open repair has recurred consider a laparoscopic approach, but if a laparoscopic repair has recurred consider an open approach.

Repair a recurrent inguinal hernia through unscarred tissue: that is, if an open repair has recurred consider a laparoscopic approach, but if a laparoscopic repair has recurred consider an open approach.

Bilateral inguinal hernia repairs are usually repaired laparoscopically as the operation is quicker. When repaired openly at the same time, the results are slightly inferior to separate repairs.

Bilateral inguinal hernia repairs are usually repaired laparoscopically as the operation is quicker. When repaired openly at the same time, the results are slightly inferior to separate repairs.

For obese patients laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair is often easier.

For obese patients laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair is often easier.

Undertake open repairs of large indirect inguinoscrotal hernias and urgent operations for hernias which may have strangulated.

Undertake open repairs of large indirect inguinoscrotal hernias and urgent operations for hernias which may have strangulated.

Avoid a laparoscopic approach if there has been previous lower abdominal surgery as a clear pre-peritoneal plane is difficult to find. Avoid it following previous open prostatectomy or procedures for urinary incontinence, but previous appendicectomy does not usually preclude it. A TAPP repair may be difficult or even hazardous if there are intraperitoneal adhesions following previous lower abdominal surgery.

Avoid a laparoscopic approach if there has been previous lower abdominal surgery as a clear pre-peritoneal plane is difficult to find. Avoid it following previous open prostatectomy or procedures for urinary incontinence, but previous appendicectomy does not usually preclude it. A TAPP repair may be difficult or even hazardous if there are intraperitoneal adhesions following previous lower abdominal surgery.

Select an open approach if there is an increased risk of bleeding such as anticoagulant therapy (even if was stopped preoperatively) or anti-platelet therapy such as clopidogrel, since bleeding can be more difficult to control than during the open operation.

Select an open approach if there is an increased risk of bleeding such as anticoagulant therapy (even if was stopped preoperatively) or anti-platelet therapy such as clopidogrel, since bleeding can be more difficult to control than during the open operation.

Inspect

Prepare

OPEN MESH INGUINAL HERNIA REPAIR (Lichtenstein Repair)

Local anaesthesia for inguinal hernia repair

Access

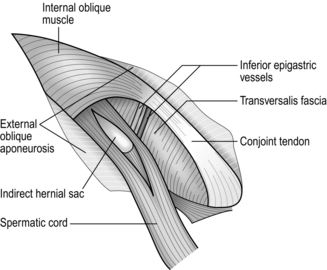

Assess (Fig. 6.1)

Hernia sac

Indirect sac

Large indirect sac

Sliding indirect sac

Direct sac

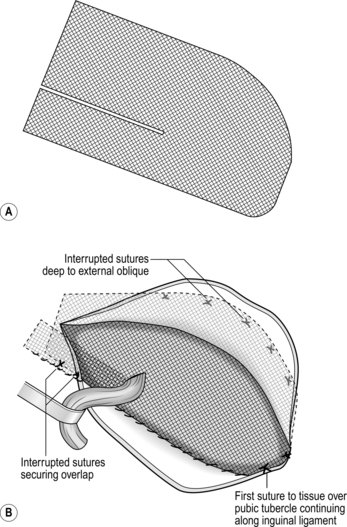

Action

Postoperative management

Complications of open inguinal hernia repair

OPEN RECURRENT INGUINAL HERNIA REPAIR

Appraise

Access

Assess

Repair

OPEN STRANGULATED INGUINAL HERNIA REPAIR

Appraise

Prepare

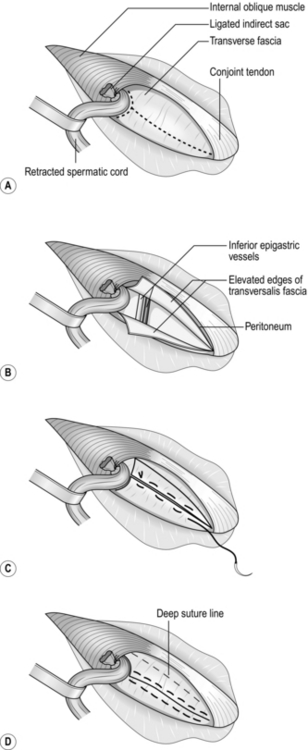

Assess

Action