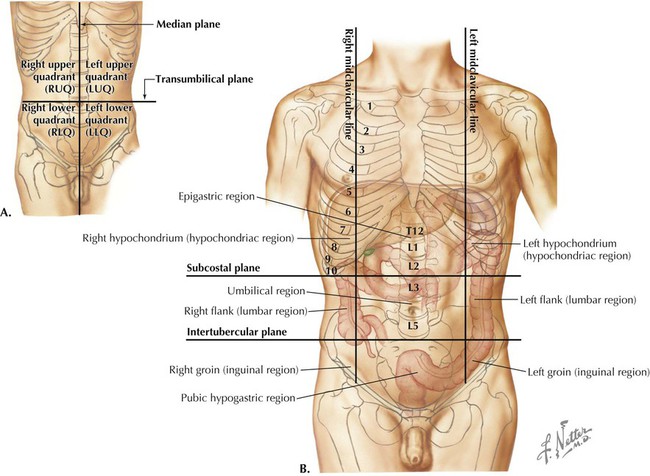

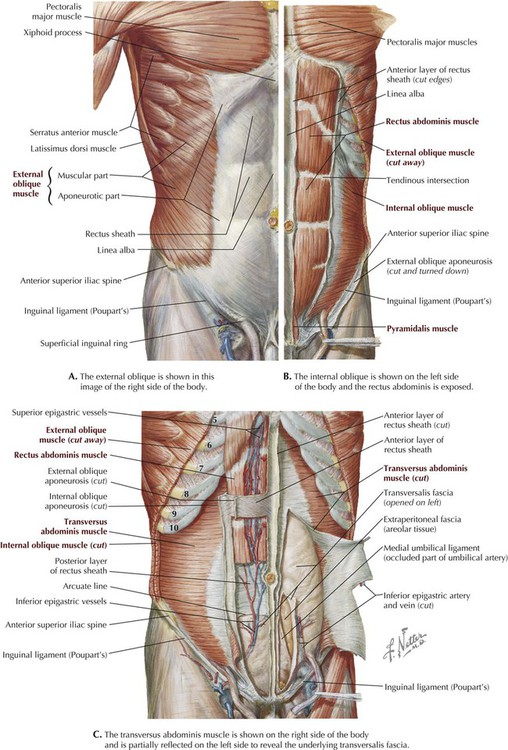

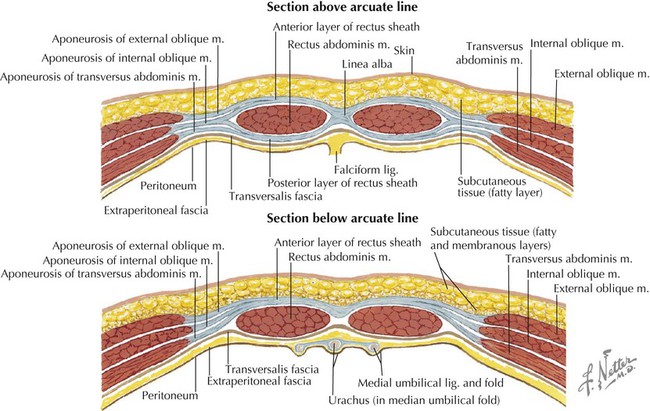

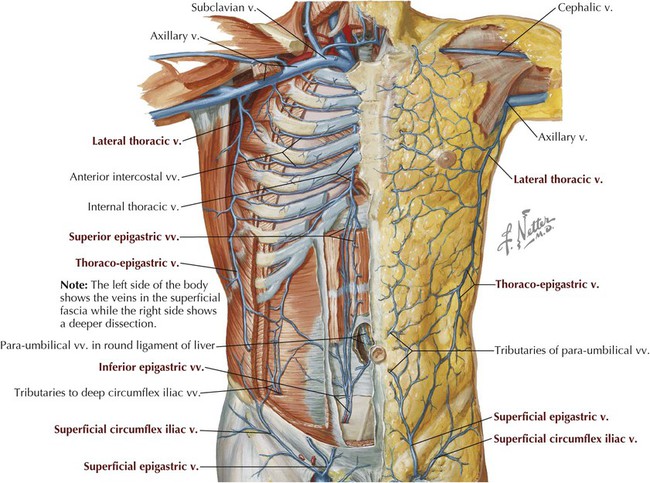

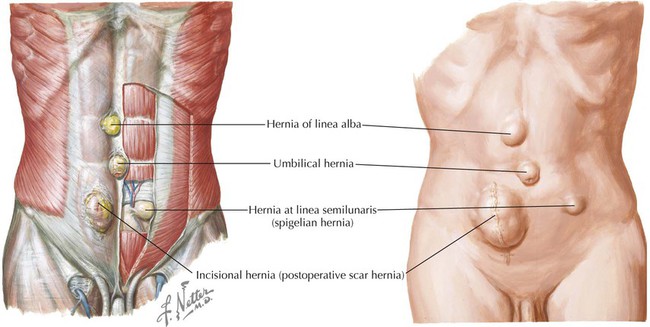

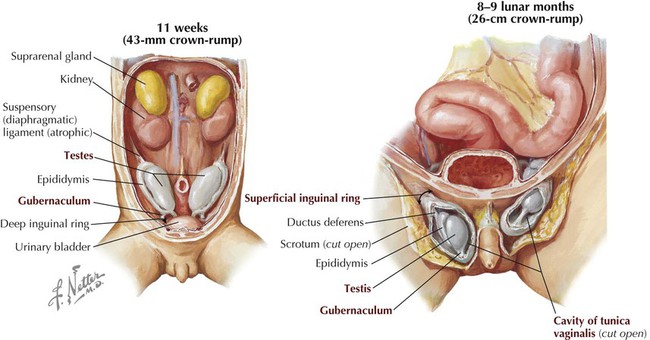

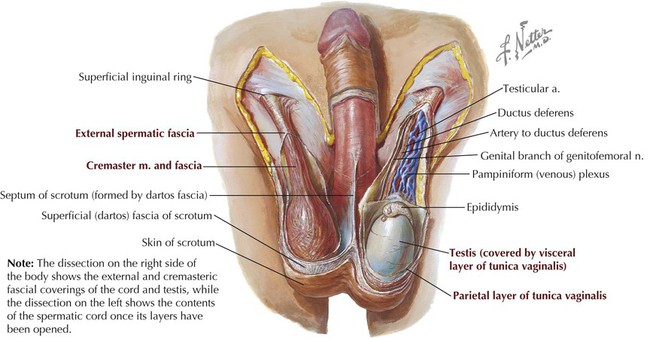

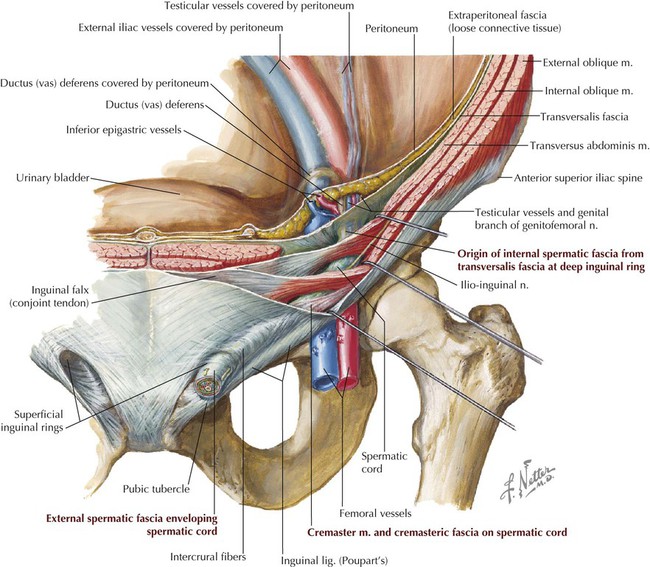

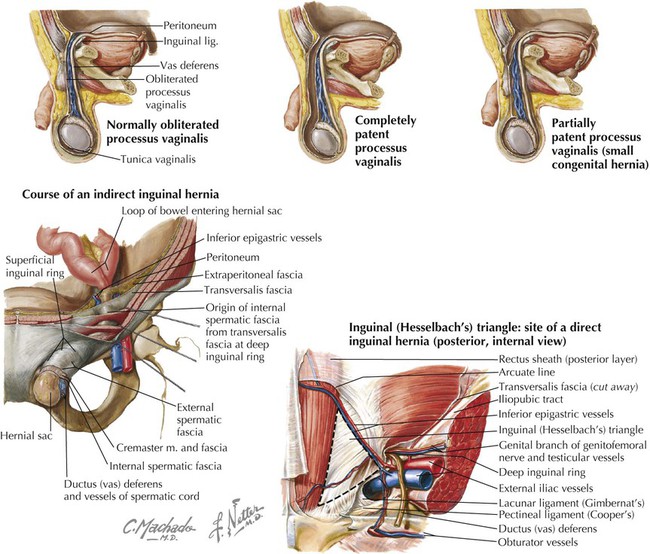

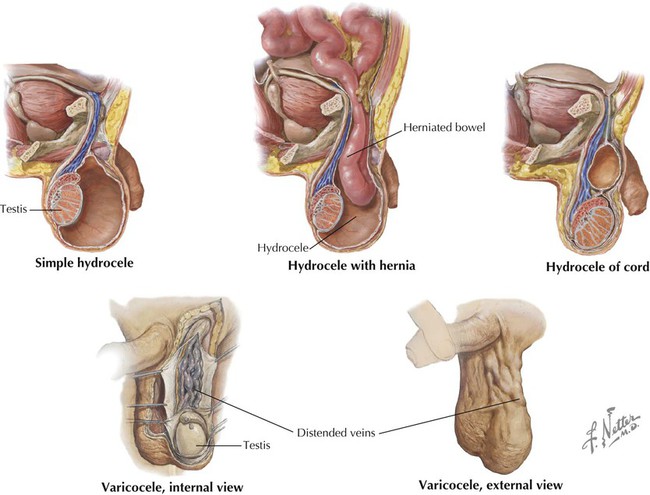

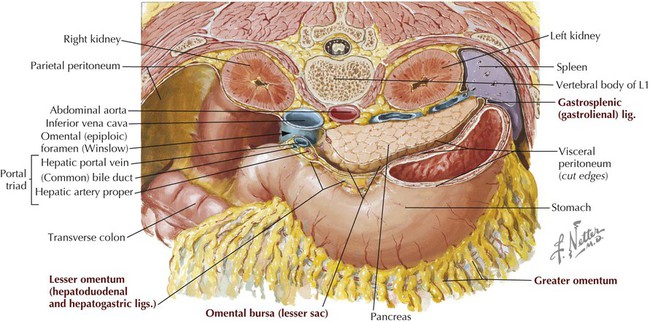

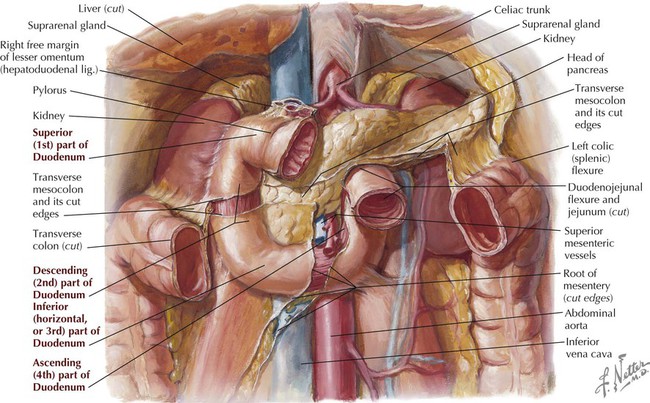

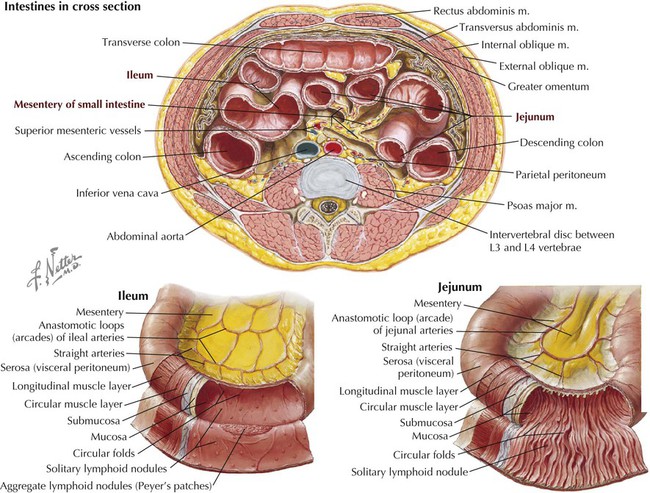

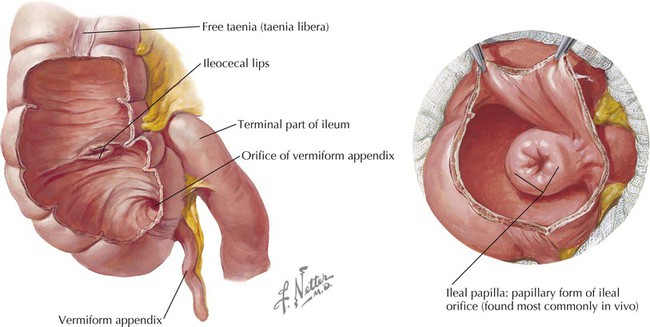

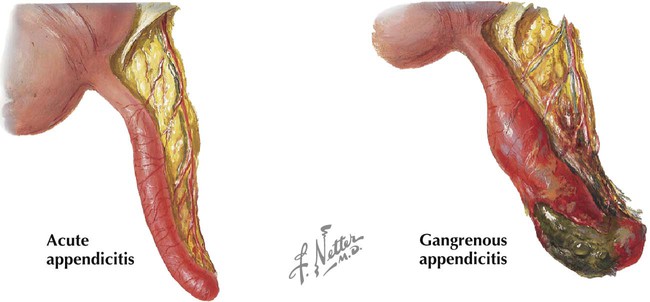

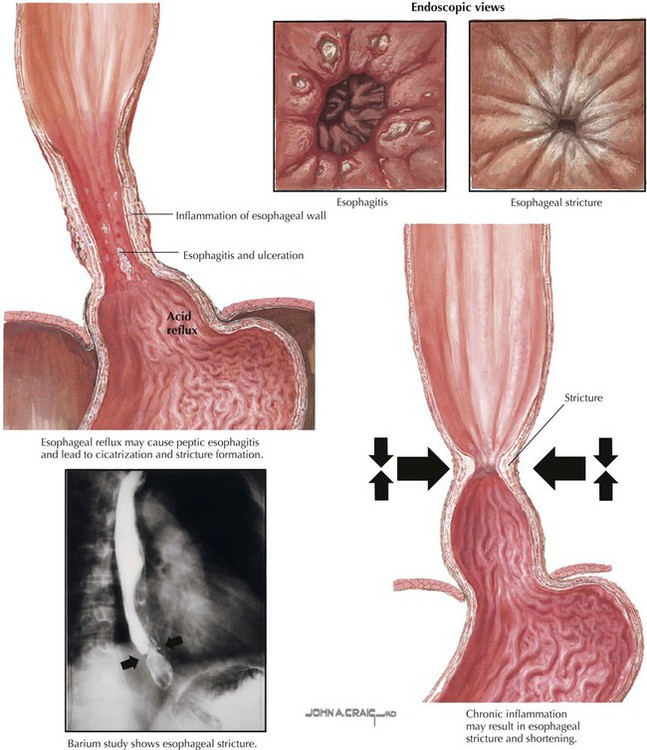

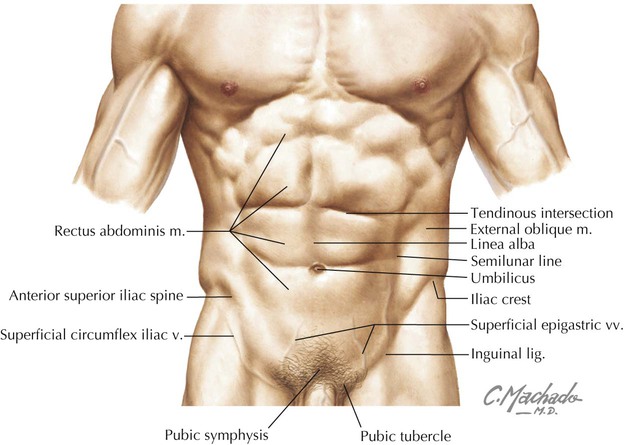

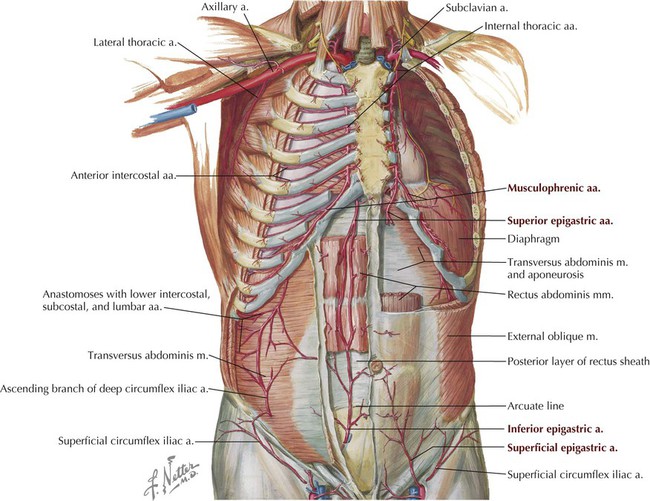

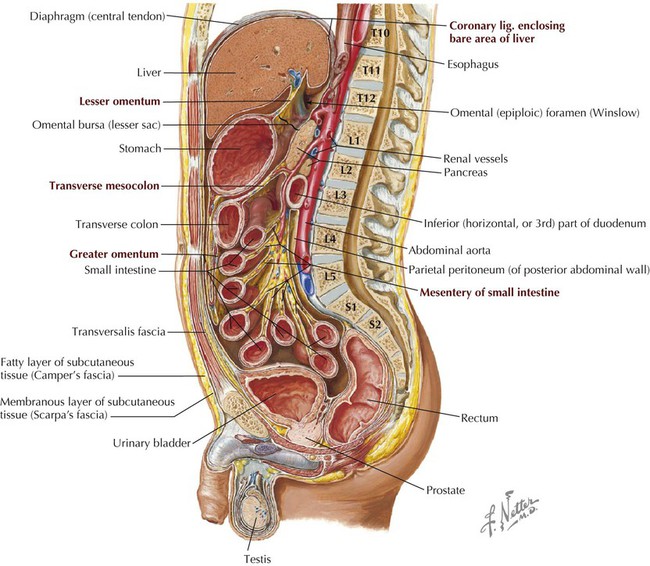

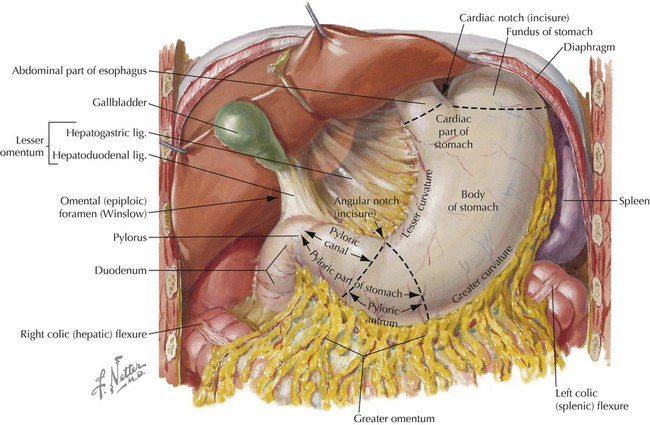

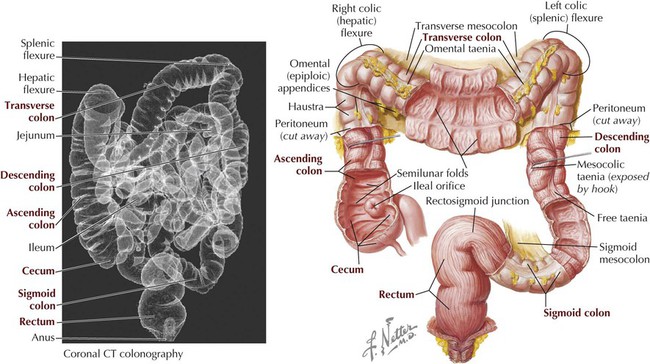

• Layers of skeletal muscle that line the abdominal walls and assist in respiration and, by increasing intraabdominal pressure, facilitate micturition (urination), defecation (bowel movement), and childbirth. • The abdominal cavity, a peritoneal lined cavity that is continuous with the pelvic cavity inferiorly and contains the abdominal viscera (organs). • Visceral structures that lie within the abdominal peritoneal cavity (intraperitoneal) and include the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and its associated organs, the spleen, and the urinary system (kidneys and ureters), which is located retroperitoneally behind and outside the cavity but anterior to the posterior abdominal wall muscles. Key surface anatomy features of the anterolateral abdominal wall include the following (Fig. 4-1): • Rectus sheath: a fascial sheath containing the rectus abdominis muscle, which runs from the pubic symphysis and crests to the xiphoid process and fifth to seventh costal cartilages. • Linea alba: literally the “white line”; a relatively avascular midline subcutaneous band of fibrous tissue where the fascial aponeuroses of the rectus sheath from each side interdigitate in the midline. • Semilunar line: the lateral border of the rectus abdominis muscle in the rectus sheath. • Tendinous intersections: transverse skin grooves that demarcate transverse fibrous attachment points of the rectus sheath to the underlying rectus abdominis muscle. • Umbilicus: the site that marks the T10 dermatome, lying at the level of the intervertebral disc between L3 and L4; the former attachment site of the umbilical cord. • Iliac crest: the rim of the ilium, which lies at about the level of the L4 vertebra. • Inguinal ligament: a ligament composed of the aponeurotic fibers of the external abdominal oblique muscle, which lies deep to a skin crease that marks the division between the lower abdominal wall and thigh of the lower limb. Clinically, the abdominal wall is divided descriptively into quadrants or regions so that both the underlying visceral structures and the pain or pathology associated with these structures can be localized and topographically described. Common clinical descriptions use either quadrants or the nine descriptive regions, demarcated by two vertical midclavicular lines and two horizontal lines: the subcostal and intertubercular planes (Fig. 4-2 and Table 4-1). TABLE 4-1 Clinical Planes of Reference for Abdomen The layers of the abdominal wall include the following: • Superficial fascia (subcutaneous tissue): a single, fatty connective tissue layer below the level of the umbilicus that divides into a more superficial fatty layer (Camper’s fascia) and a deeper membranous layer (Scarpa’s fascia; see Fig. 4-11). • Investing fascia: tissue that covers the muscle layers. • Abdominal muscles: three flat layers, similar to the thoracic wall musculature, except in the anterior midregion where the vertically oriented rectus abdominis muscle lies in the rectus sheath. • Endoabdominal fascia: tissue that is unremarkable except for a thicker portion called the transversalis fascia, which usually lines the inner aspect of the transversus abdominis muscle; it is continuous with fascia on the underside of the diaphragm, fascia of the posterior abdominal muscles, and fascia of the pelvic muscles. • Extraperitoneal (fascia) fat: connective tissue that is variable in thickness and contains a variable amount of fat. • Peritoneum: thin serous membrane that lines the inner aspect of the abdominal wall (parietal peritoneum) and occasionally reflects off the walls as a mesentery to invest partially or completely various visceral structures (visceral peritoneum). The muscles of the anterolateral abdominal wall include three flat layers that are continuations of the three layers in the thoracic wall (Fig. 4-3). These include two abdominal oblique muscles and the transversus abdominis muscle (Table 4-2). In the midregion a vertically oriented pair of rectus abdominis muscles lies within the rectus sheath and extends from the pubic symphysis and crest to the xiphoid process and costal cartilages 5 to 7 superiorly. The small pyramidalis muscle (Fig. 4-3, B) is inconsistent and clinically insignificant. TABLE 4-2 Principal Muscles of Anterolateral Abdominal Wall The rectus sheath encloses the vertically running rectus abdominis muscle (and inconsistent pyramidalis), the superior and inferior epigastric vessels, the lymphatics, and the ventral rami of T7-L1 nerves, which enter the sheath along its lateral margins (Fig. 4-3, C). The superior three quarters of the rectus abdominis is completely enveloped within the rectus sheath, and the inferior one quarter is supported posteriorly only by the transversalis fascia, extraperitoneal fat, and peritoneum; the site of this transition is called the arcuate line (Fig. 4-4 and Table 4-3). TABLE 4-3 Aponeuroses and Layers Forming Rectus Sheath* The segmental innervation of the anterolateral abdominal skin and muscles is by ventral rami of T7-L1. The blood supply includes the following arteries (Figs. 4-3, C, and 4-5): • Musculophrenic: a terminal branch of the internal thoracic artery that courses along the costal margin. • Superior epigastric: arises from the terminal end of the internal thoracic artery and anastomoses with the inferior epigastric artery at the level of the umbilicus. • Inferior epigastric: arises from the external iliac artery and anastomoses with the superior epigastric artery. • Superficial circumflex iliac: arises from the femoral artery and anastomoses with the deep circumflex iliac artery. • Superficial epigastric: arises from the femoral artery and courses toward the umbilicus. • External pudendal: arises from the femoral artery and courses toward the pubis. Superficial and deeper veins accompany these arteries, but, as elsewhere in the body, they form extensive anastomoses with each other to facilitate venous return to the heart (Fig. 4-6 and Table 4-4). TABLE 4-4 Principal Veins of Anterolateral Abdominal Wall • Axillary nodes: superficial drainage above the umbilicus • Superficial inguinal nodes: superficial drainage below the umbilicus • Parasternal nodes: deep drainage along the internal thoracic vessels • Lumbar nodes: deep drainage internally to the nodes along the abdominal aorta • External iliac nodes: deep drainage along the external iliac vessels The inguinal region is demarcated by the inguinal ligament, the inferior border of the external abdominal oblique aponeurosis, which is folded under on itself and attaches to the anterior superior iliac spine and extends inferomedially to attach to the pubic tubercle (see Figs. 4-1 and 4-3, B). Medially, the inguinal ligament flares into the crescent-shaped lacunar ligament that attaches to the pecten pubis of the pubic bone (Fig. 4-7). Fibers from the lacunar ligament also course internally along the pelvic brim as the pectineal ligament (see Clinical Focus 4-2). A thickened inferior margin of the transversalis fascia, called the iliopubic tract, runs parallel to the inguinal ligament but deep to it and reinforces the medial portion of the inguinal canal. In males the testes descend into the pelvis but then continue their descent through the inguinal canal (formed by the processus vaginalis) and into the scrotum, which is the male homologue of the female labia majora (Fig. 4-8). This descent through the inguinal canal occurs around the 26th week of development, usually over several days. The gubernaculum terminates in the scrotum and anchors the testis to the floor of the scrotum. A small pouch of the processus vaginalis called the tunica vaginalis persists and partially envelops the testis. In both genders the processus vaginalis then normally seals itself and is obliterated. Sometimes this fusion does not occur or is incomplete, especially in males, probably caused by descent of the testes through the inguinal canal. Consequently, a weakness may persist in the abdominal wall that can lead to inguinal hernias. As the testes descend, they bring their accompanying spermatic cord along with them and, as these structures pass through the inguinal canal, they too become ensheathed within the layers of the anterior abdominal wall (Fig. 4-9). The spermatic cord enters the inguinal canal at the deep inguinal ring (an outpouching in the transversalis fascia lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels) and exits the 4-cm-long canal via the superficial inguinal ring (superior to the pubic tubercle) before passing into the scrotum, where it suspends the testis. In females the only structure in the inguinal canal is the fibrofatty remnant of the round ligament of the uterus, which terminates in the labia majora. The contents in the spermatic cord include the following (Fig. 4-9): • Testicular artery, artery of the ductus deferens, and cremasteric artery • Pampiniform plexus of veins (testicular veins) • Autonomic nerve fibers (sympathetic efferents and visceral afferents) coursing on the arteries and ductus deferens • Genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve (innervates cremaster muscle) Layers of the spermatic cord include the following (see Fig. 4-9): • External spermatic fascia: derived from the external abdominal oblique aponeurosis • Cremasteric (middle spermatic) fascia: derived from the internal abdominal oblique muscle • Internal spermatic fascia: derived from the transversalis fascia The features of the inguinal canal include its anatomical boundaries, as shown in Figure 4-10 and summarized in Table 4-5. Note that the deep inguinal ring begins internally as an outpouching of the transversalis fascia lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels, and that the superficial inguinal ring is the opening in the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique muscle. Aponeurotic fibers at the superficial ring envelop the emerging spermatic cord medially (medial crus), over its top (intercrural fibers), and laterally (lateral crus) (Fig. 4-10). TABLE 4-5 Features and Boundaries of Inguinal Canal The abdominal viscera are contained within a serous membrane–lined recess called the abdominopelvic cavity (sometimes just “abdominal” or “peritoneal” cavity) or lie in a retroperitoneal position adjacent to this cavity, often with only their anterior surface covered by peritoneum (e.g., the kidneys and ureters). The abdominopelvic cavity extends from the abdominal diaphragm inferiorly to the floor of the pelvis (Fig. 4-11). The parietal peritoneum lines the inner aspect of the abdominal wall and thus is innervated by somatic afferent fibers of the ventral rami of the spinal nerves innervating the abdominal musculature. Inflammation or trauma to the parietal peritoneum therefore presents as well-localized pain. The visceral peritoneum, on the other hand, is innervated by visceral afferent fibers carried in the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves. Pain associated with visceral peritoneum thus is more poorly localized, giving rise to referred pain (see Table 4-12). The abdominopelvic cavity is further subdivided into the following (Figs. 4-11 and 4-12): • Greater sac: most of the abdominopelvic cavity • Lesser sac: also called the omental bursa; an irregular part of the peritoneal cavity that forms a cul-de-sac space posterior to the stomach and anterior to the retroperitoneal pancreas; it communicates with the greater sac via the epiploic foramen (of Winslow). In addition to the mesenteries that suspend the bowel, the peritoneal cavity contains a variety of double-layered folds of peritoneum, including the omenta (attached to the stomach) and peritoneal ligaments. These are not “ligaments” in the traditional sense but rather short, distinct mesenteries that connect structures (for which they are named) together or to the abdominal wall (Table 4-6). Some of these structures are shown in Figures 4-11 and 4-12, and we will encounter the others later in the chapter as we describe the abdominal contents. TABLE 4-6 Mesenteries, Omenta, and Peritoneal Ligaments The distal end of the esophagus passes through the right crus of the abdominal diaphragm at about the level of the T10 vertebra and terminates in the cardiac portion of the stomach (Fig. 4-13). The stomach is a dilated, saclike portion of the GI tract that exhibits significant variation in size and configuration, terminating at the thick, smooth muscle sphincter (pyloric sphincter) by joining the first portion of the duodenum. The stomach is tethered superiorly by the lesser omentum (gastrohepatic ligament portion; Table 4-6) extending from its lesser curvature and is attached along its greater curvature to the greater omentum and the gastrosplenic ligament (see Figs. 4-12 and 4-13). Generally, the J-shaped stomach is divided into the following regions (Fig. 4-13 and Table 4-7): TABLE 4-7 Descriptive Features of the Stomach The interior of the unstretched stomach is lined with prominent longitudinal mucosal gastric folds called rugae, which become more evident as they approach the pyloric region. As an embryonic foregut derivative, the stomach’s blood supply comes from the celiac trunk and its major branches (see Embryology). • Duodenum: about 25 cm long and largely retroperitoneal • Jejunum: about 2.5 meters long and suspended by a mesentery The duodenum is the first portion of the small intestine and descriptively is divided into four parts (Table 4-8). Most of the C-shaped duodenum is retroperitoneal and ends at the duodenojejunal flexure, where it is tethered by a musculoperitoneal fold called the suspensory ligament of the duodenum (ligament of Treitz) (Fig. 4-14). TABLE 4-8 The jejunum and ileum are both suspended in an elaborate mesentery. The jejunum is recognizable from the ileum because the jejunum (Fig. 4-15): • Occupies the left upper quadrant of the abdomen. • Is larger in diameter than the ileum. • Has mesentery with less fat. • Has arterial branches with fewer arcades and longer vasa recta. • Internally has mucosal folds that are higher and more numerous, which increases the surface area for absorption. The small intestine ends at the ileocecal junction, where a sphincter called the ileocecal valve controls the passage of ileal contents into the cecum (Fig. 4-16). The valve is actually two internal mucosal folds that cover a thickened smooth muscle sphincter. The large intestine is about 1.5 meters long, extending from the cecum to the anal canal, and includes the following segments (Figs. 4-16 and 4-17): • Cecum: a pouch that is connected to the ascending colon and the ileum; it extends below the ileocecal junction, although it is not suspended by a mesentery. • Appendix: a narrow tube of variable length (usually 7-10 cm) that contains numerous lymphoid nodules and is suspended by mesentery called the meso-appendix. • Ascending colon: is retroperitoneal and ascends on the right flank to reach the liver, where it bends into the right colic (hepatic) flexure. • Transverse colon: is suspended by a mesentery, the transverse mesocolon, and runs transversely from the right hypochondrium to the left, where it bends to form the left colic (splenic) flexure. • Descending colon: is retroperitoneal and descends along the left flank to join the sigmoid colon in the left groin region. • Sigmoid colon: is suspended by a mesentery, the sigmoid mesocolon, and forms a variable loop of bowel that runs medially to join the midline rectum in the pelvis. • Rectum and anal canal: are retroperitoneal and extend from the middle sacrum to the anus (see Chapter 5). Lateral to the ascending and the descending colon lie the right and the left paracolic gutters, respectively. These depressions provide conduits for abdominal fluids to pass from region to region, largely dependent on gravity. Functionally the colon (ascending colon through the sigmoid part) absorbs water and important ions from the feces. It then compacts the feces for delivery to the rectum. Features of the large intestine include the following (Fig. 4-17): • Taeniae coli: three longitudinal bands of smooth muscle that are visible on the cecum and colon’s surface and assist in peristalsis. • Haustra: sacculations of the colon created by the contracting taeniae coli. • Omental appendices: small fat accumulations that are covered by visceral peritoneum and hang from the colon. • Greater luminal diameter: the large intestine has a larger luminal diameter than the small intestine.

Abdomen

1 Introduction

2 Surface Anatomy

Key Landmarks

Surface Topography

PLANE OF REFERENCE

DEFINITION

Median

Vertical plane from xiphoid process to pubic symphysis

Transumbilical

Horizontal plane across umbilicus; these planes divide the abdomen into quadrants.

Subcostal

Horizontal plane across inferior margin of 10th costal cartilage

Intertubercular

Horizontal plane across tubercles of ilium and body of L5 vertebra

Midclavicular

Two vertical planes through midpoint of clavicles; these planes divide the abdomen into nine regions.

3 Anterolateral Abdominal Wall

Layers

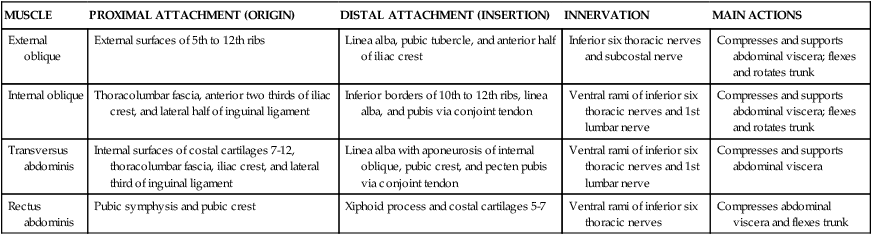

Muscles

MUSCLE

PROXIMAL ATTACHMENT (ORIGIN)

DISTAL ATTACHMENT (INSERTION)

INNERVATION

MAIN ACTIONS

External oblique

External surfaces of 5th to 12th ribs

Linea alba, pubic tubercle, and anterior half of iliac crest

Inferior six thoracic nerves and subcostal nerve

Compresses and supports abdominal viscera; flexes and rotates trunk

Internal oblique

Thoracolumbar fascia, anterior two thirds of iliac crest, and lateral half of inguinal ligament

Inferior borders of 10th to 12th ribs, linea alba, and pubis via conjoint tendon

Ventral rami of inferior six thoracic nerves and 1st lumbar nerve

Compresses and supports abdominal viscera; flexes and rotates trunk

Transversus abdominis

Internal surfaces of costal cartilages 7-12, thoracolumbar fascia, iliac crest, and lateral third of inguinal ligament

Linea alba with aponeurosis of internal oblique, pubic crest, and pecten pubis via conjoint tendon

Ventral rami of inferior six thoracic nerves and 1st lumbar nerve

Compresses and supports abdominal viscera

Rectus abdominis

Pubic symphysis and pubic crest

Xiphoid process and costal cartilages 5-7

Ventral rami of inferior six thoracic nerves

Compresses abdominal viscera and flexes trunk

Rectus Sheath

LAYER

COMMENT

Anterior lamina above arcuate line

Formed by fused aponeuroses of external and internal abdominal oblique muscles

Posterior lamina above arcuate line

Formed by fused aponeuroses of internal abdominal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles

Below arcuate line

All three muscle aponeuroses fuse to form anterior lamina, with rectus abdominis in contact only with transversalis fascia posteriorly

Innervation and Blood Supply

VEIN

COURSE

Superficial epigastric

Drains into femoral vein

Superficial circumflex iliac

Drains into femoral vein and parallels inguinal ligament

Inferior epigastric

Drains into external iliac vein

Superior epigastric

Drains into internal thoracic vein

Thoraco-epigastric

Anastomoses between superficial epigastric and lateral thoracic

Lateral thoracic

Drains into axillary vein

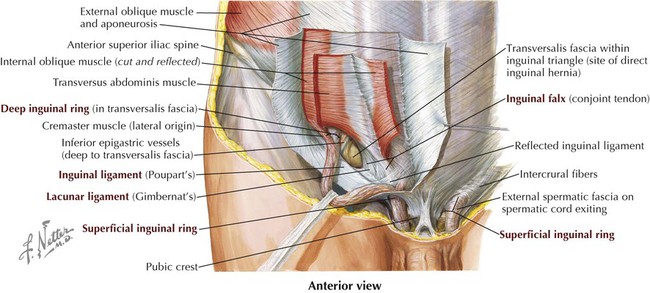

4 Inguinal Region

Inguinal Canal

FEATURE

COMMENT

Superficial ring

Medial opening in external abdominal oblique aponeurosis

Deep ring

Evagination of transversalis fascia lateral to inferior epigastric vessels, forming internal layer of spermatic fascia

Inguinal canal

Tunnel extending from deep to superficial ring, paralleling inguinal ligament; transmits spermatic cord in males or round ligament of uterus in females)

Anterior wall

Aponeuroses of external and internal abdominal oblique muscles

Posterior wall

Transversalis fascia; medially includes conjoint tendon

Roof

Arching muscle fibers of internal abdominal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles

Floor

Medial half of inguinal ligament, and medially by lacunar ligament, an expanded extension of the ligament

Inguinal ligament

Ligament extending between anterior superior iliac spine and pubic tubercle; folded inferior border of external abdominal oblique aponeurosis

5 Abdominal Viscera

Peritoneal Cavity

Observe the parietal peritoneum lining the cavity walls, the mesenteries suspending various portions of the viscera, and the lesser and greater sacs. (From Atlas of human anatomy, ed 6, Plate 321.)

FEATURE

DESCRIPTION

Greater omentum

“Apron” of peritoneum hanging from greater curvature of stomach, folding back on itself and attaching to transverse colon

Lesser omentum

Double layer of peritoneum extending from lesser curvature of stomach and proximal duodenum to inferior surface of liver

Mesenteries

Double fold of peritoneum suspending parts of bowel and conveying vessels, lymphatics, and nerves of bowel (meso-appendix, transverse mesocolon, sigmoid mesocolon)

Peritoneal ligaments

Double layer of peritoneum attaching viscera to walls or to other viscera

Gastrocolic ligament

Portion of greater omentum that extends from greater curvature of stomach to transverse colon

Gastrosplenic ligament

Left part of greater omentum that extends from hilum of spleen to greater curvature of stomach

Splenorenal ligament

Connects spleen and left kidney

Gastrophrenic ligament

Portion of greater omentum that extends from fundus to diaphragm

Phrenocolic ligament

Extends from left colic flexure to diaphragm

Hepatorenal ligament

Connects liver to right kidney

Hepatogastric ligament

Portion of lesser omentum that extends from liver to lesser curvature of stomach

Hepatoduodenal ligament

Portion of lesser omentum that extends from liver to 1st part of duodenum

Falciform ligament

Extends from liver to anterior abdominal wall

Ligamentum teres hepatis

Obliterated left umbilical vein in free margin of falciform ligament

Coronary ligaments

Reflections of peritoneum from superior aspect of liver to diaphragm

Ligamentum venosum

Fibrous remnant of obliterated ductus venosus

Suspensory ligament of ovary

Extends from lateral pelvic wall to ovary

Ovarian ligament

Connects ovary to uterus (part of gubernaculum)

Round ligament of uterus

Extends from uterus to deep inguinal ring (part of gubernaculum)

Abdominal Organs

Abdominal Esophagus and Stomach

FEATURE

DESCRIPTION

Lesser curvature

Right border of stomach; lesser omentum attaches here and extends to liver

Greater curvature

Convex border with greater omentum suspended from its margin

Cardiac part

Area of stomach that communicates with esophagus superiorly

Fundus

Superior part just under left dome of diaphragm

Body

Main part between fundus and pyloric antrum

Pyloric part

Portion divided into proximal antrum and distal canal

Pylorus

Site of pyloric sphincter muscle; joins 1st part of duodenum

Small Intestine

PART OF DUODENUM

DESCRIPTION

Superior

First part; attachment site for hepatoduodenal ligament of lesser omentum; technically not retroperitoneal for the first 1 or 2 inches (2.5-5 cm)

Descending

Second part; site where bile and pancreatic ducts empty

Inferior

Third part; crosses inferior vena cava and aorta and is crossed anteriorly by mesenteric vessels

Ascending

Fourth part; tethered by suspensory ligament at duodenojejunal flexure

Large Intestine

Abdomen