LEARNING OBJECTIVES

To conceptualize “professionalism” in terms of behaviors.

To define the roles of physicians, teams, healthcare systems, and the external environment in supporting professionalism.

To explain the role of physicians in influencing both the microsystem and the broader environment to enhance professionalism.

INTRODUCTION

Dr. Jackson is a 2nd-year medical resident doing a rotation on the wards of a teaching hospital. He was entering an order for an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor for Mrs. Shaw, an 80-year-old patient with congestive heart failure, when the chief resident interrupted him to discuss Mrs. Fraser, a patient with asthma who needed additional bronchodilator treatment. When Dr. Jackson returned to the computer, he incorrectly entered the order for salbutamol into the chart of Mrs. Shaw. The nurse noticed that this was a medication that had not previously been prescribed for Mrs. Shaw but did not question the order. The next day, the nurse sees Dr. Jackson during ward rounds and asks why the team started the salbutamol on Mrs. Shaw. When they realize there has been a medication error, the nurse and resident feel uncertain about whether they should tell the patient because she has not suffered any physical problems from the wrong drug. If they tell her, how should they do this and who should share the information with her? How might this be prevented in the hospital in the future? Dr. Jackson remembers he attended a lecture that mentioned that the hospital has an office that helps physicians with disclosing medical errors.

This case of a medication error illustrates a common occurrence and one in which multiple healthcare professionals play a role. Disclosing the error to the patient is a professional responsibility for the entire healthcare team. Dr. Jackson and the nurse will meet to plan how to tell Mrs. Shaw what occurred. The hospital has staff members who are experts in disclosing errors who will help Dr. Jackson and the nurse to prepare for this challenging disclosure conversation. Staff in the hospital’s quality improvement department will conduct an analysis of the error to see how this error occurred and how they can prevent similar mistakes in the future. The hospital prides itself on compliance with the external standards set by the Joint Commission and the National Quality Forum Safe Practices regarding disclosing errors.

A medical error like this one is a challenge to our professionalism. Nobody working in healthcare intends to make a mistake, and yet, they occur routinely despite our best efforts to prevent them. Disclosing the error is a difficult task, but undertaking that conversation with the patient is an indication of the professionalism of each part of the system—the physician, the nurse, residents, medical students, and the hospital administration. Each player in the system, from an individual physician to the healthcare system itself, can demonstrate a high level of professionalism through behaviors that support the disclosure to the patient. Demonstrating professionalism is a team effort.

In this chapter, we describe a behavioral and systems approach to professionalism. Our basic tenets are the following:

Professionalism is demonstrated through a set of behaviors that can be observed;

The behaviors can be observed in four key domains:

the interaction between clinicians and patients/families;

the interaction among team members;

the practice settings (i.e., hospital, outpatient clinics, healthcare systems);

the professional organizations and external environment influencing care.

We have found this framework for describing professionalism to be a practical and useful approach for physicians, nurses, and healthcare administrators who seek to provide the highest quality of care (Lesser et al, 2010). We use examples of a variety of healthcare providers including practicing physicians, medical students, residents, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and others, to illustrate our points.

WHY FOCUS ON BEHAVIORS?

When we begin to discuss the topic of “professionalism” during grand rounds, we often see that our audiences appear to be uninterested or even irritated. That reaction is understandable as our colleagues may think professionalism is some abstract concept, a theoretical aspirational goal, or a set of principles distant from clinical practice. They may believe they already have the right attitude toward patients and that this attitude will guide them to do the right thing when the circumstances require them to do so. They may be thinking, “What could this grand rounds speaker teach us that has any practical application to our daily lives?”

Thinking about professionalism as a set of behaviors that can be demonstrated in our everyday work has helped us to make “professionalism” much more practical and relevant. Behaviors, enabled by specific skills, are observable and can be learned (Lucey & Souba, 2010). The skills can be practiced and improved. When adult learners enter medical school with the desire to exhibit the values of professionalism (Leach, 2004), they have no experience in maintaining professional behavior under the challenging circumstances that confront practicing clinicians. Achieving professionalism in practice requires the capacity to navigate competing priorities and make sound judgments, often under pressure. Simply knowing right from wrong or having an internal compass does not suffice. Demonstrating professionalism is based on a set of practiced skills honed over time—skills we call on daily. The critical message of the framework is that professionalism is not a static or amorphous construct. Rather, it can be defined in concrete behaviors and should be understood as a lived approach to the practice of medicine that emanates, from physicians, to many varied interactions in the healthcare delivery system.

IDENTIFYING PROFESSIONALISM BEHAVIORS

In order to articulate a key set of behaviors, we revisit the Physician Charter on Medical Professionalism developed by the ABIM Foundation, American College of Physicians, and the European Federation of Internal Medicine. Since the creation of the Charter in 2002, it has become widely accepted around the world, and more than 300 medical organizations worldwide have endorsed it. The Charter offers a definition of professionalism based on three principles and a set of 10 commitments (Table 1-1) (ABIM Foundation, 2002).

Three Fundamental Principles

|

Ten Commitments (commitments to…)

|

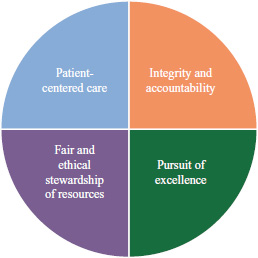

Most physicians agree with the Charter’s core commitments. For example, in a 2007 survey, 96% of physicians agreed with the principle of putting the patient’s welfare above the physician’s financial interest, and 98% agreed with the commitment to minimize healthcare disparities due to patient race or sex (Campbell et al, 2007). Because most physicians agree with the principles and commitments, this is a good starting point for articulating a set of behaviors that demonstrate professionalism in action. In order to operationalize the Charter into observable behaviors that can be demonstrated, we grouped the 10 commitments into four core values (Figure 1-1).

Table 1-2 displays the 10 commitments and how we grouped them into the four core values. Our goal is to make it clear that healthcare professionals can live the values of professionalism every day by exhibiting these behaviors.

| Core values | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient-centered care | Integrity and accountability | Pursuit of excellence | Fair and ethical stewardship of healthcare resources | ||

| Commitments of the Physician Charter | Professional competence | ∗ | ∗ | ||

| Honesty with patients | ∗ | ∗ | |||

| Patient confidentiality | ∗ | ||||

| Maintaining appropriate relations with patients | ∗ | ||||

| Improving quality of care | ∗ | ∗ | |||

| Improving access to care | ∗ | ||||

| Just distribution of finite resources | ∗ | ||||

| Scientific knowledge | ∗ | ||||

| Maintaining trust by managing conflicts of interest | ∗ | ||||

| Professional responsibility to maintain standards of care | ∗ | ||||

THE SYSTEMS VIEW OF PROFESSIONALISM

During a teaching session on the topic of professionalism, anesthesia residents described a difficult situation that they did not know how to handle. The residents reported that during operations, one particular senior surgeon routinely berated surgical residents, criticizing them as incompetent and humiliating them in front of the operating room staff. The anesthesia residents were not personally attacked by this surgeon, but they were embarrassed for their surgical colleagues and were angry at the surgeon for this behavior. They felt uncomfortable speaking up about it, but they wanted the behavior to stop.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree