LEARNING OBJECTIVES

To understand the history and evolution of medical professionalism.

To review key efforts to institutionalize professionalism within the arenas of medical education and clinical practice.

To frame some of the modern issues of conflict-of-interest, duty hours, and social media in the light of professionalism.

To link the concepts of professionalism with that of the hidden curriculum.

INTRODUCTION

This chapter examines the history and evolution of medicine’s modern-day professionalism movement. The brief discussion in this chapter is partial and not comprehensive, and is intended to provide readers with some historical context. In particular, we think it is useful to realize that medical professionalism, while it has roots back into the 1600s, has only recently received a good deal of attention in medical literature and medical education. Furthermore, understanding this history may allow readers to reflect on the present day challenges facing medicine and consider how professionalism will continue to evolve.

ROOTS

For the last several hundred years, medicine has been considered, and considered itself to be, a profession. Historical documents reflect this view. During the Great Plague of London in 1666, an apothecary William Boghurst argued:

Every man that undertakes to be of a profession, or takes upon himself an office must take all parts of it, the good and the evil, the pleasure and the pain, the profit and the inconveniences all together and not pick and choose; for Ministers must preach, Captains must fight and Physicians attend upon the sick (Huber & Wynia, 2004).

In 1803, Thomas Percival published his pivotal book entitled Medical Ethics (Percival, 1803). Percival labeled medicine as a “profession,” and he characterized the practice of medicine as a “public trust.” Percival recast medical ethics as a collective rather than an individual physician responsibility “essentially creating the notion of medical professionalism” (Wynia & Kurlander, 2007). Although the term “profession” would not be a common descriptor for most of the second millennium, the historical connections of medicine to the guild structure of medieval Europe and to the notions of skilled labor and apprenticeship training, is well documented (Sox, 2007).

Occupational claims of expertise were not always supported by the public. By the 1700s and 1800s, there were widespread signs that the public held a deep distrust of trade and professional groups over the tendency of such groups toward self-interest. Writers as disparate as Adam Smith and George Bernard Shaw framed professions as “conspiracies against the public” (Smith, 1991) or against the “laity” (Shaw, 1946), with Shaw adding an occupationally specific dagger in characterizing medicine as “a conspiracy to hide its own shortcomings.” Over time, and as documented in Paul Starr’s book The Social Transformation of American Medicine (Starr, 1984), organized medicine became strategic and proactive in its attempts to reclaim its image and to solidify its claims to professional powers and privileges—a process Starr characterized in the subtitle of his book as “the rise of a sovereign profession.” By the 1950s, medicine’s efforts were so successful that the terms “medicine” and “profession” had become linked. Physicians were viewed as professionals by virtue of their training and degree. The state and the status had become one.

Today, we live in more critical times. Questions about the legitimacy of medicine’s status as a profession have become more challenging. In this chapter, we briefly trace the history of medicine’s modern-day professionalism movement, beginning with its conceptual origins in the field of sociology and moving through more contemporary concerns with issues such as conflict-of-interest, duty hours, and social media. The professionalism movement itself is in its early adolescence, and the kinds of discord we see taking place across the current professionalism landscape speaks to the movement’s nascent status. At the same time, it is equally true that medicine’s future as a profession is not guaranteed. If present challenges are not properly addressed, organized medicine may well experience significant curtailments of its professional powers and privileges.

THE PROFESSION OF MEDICINE AND PROFESSIONALISM

Whether we are discussing historical origins or modern expressions, it is critical to differentiate between profession and professionalism. Profession is a sociological construct and a way of organizing work. Each profession is controlled by skilled workers and has its own knowledge base, organizational forms, career paths, education, and ideology, and thus its own logic for how work is carried out and valued (Freidson, 2001). Understanding how work is organized and executed, however, is different from examining the underlying ethos driving that work—and thus how professionalism functions as an occupationally specific moral imperative. Professionalism describes the core values (e.g., altruism, conscientiousness, and so on) that are shared by physicians.

Historically, attention to issues of professions predates those of professionalism. During the early 1900s, social scientists began to examine a number of occupational groups for their (potentially) professional characteristics, including accountancy, life insurance, and “handing men” (a.k.a. hiring managers) (Bloomfield, 1915). Medicine was just one of many occupations subject to such sociological scrutiny. In 1915, Abraham Flexner, whose earlier and scathing study of North American medical schools (the Flexner Report) would revolutionize medical training, published a piercing dissection of claims to professional status (Flexner, 1915). In his article, Flexner applied six criteria to analyze the professional status of a range of occupational groups, including banking, engineering, medicine, nursing, pharmacy, plumbing, and social work. He concluded that medicine had yet to realize its professional potentials because its altruistic aspirations were being undercut by its commercialist tendencies—a conclusion no doubt influenced by Flexner’s earlier encounters with the shameful state of proprietary, for-profit medical schools.

All activities may be prosecuted in the genuine professional spirit. Insofar as accepted professions are prosecuted at a mercenary or selfish level, law and medicine are ethically no better than trades.

Abraham Flexner 1915 (page 165)

In the next decade, authors continued to raise concerns about the “inherent conflict” in medicine between the need to maintain standards to protect the public and actions taken to promote the interests of the profession and individual professionals (Parsons, 1939). In 1970, Eliot Freidson began to examine how medicine as a profession operated in a protectionist and self-interested manner.

“… the critical flaw in professional autonomy … [is that] … it develops and maintains in the profession a self-deceiving view of the objectivity and reliability of knowledge and the virtues of its members. Furthermore, it encourages the profession to see itself as the sole possessor of knowledge and virtue, to be somewhat suspicious of the technical and moral capacity of other occupations, and to be at best patronizing and at worst contemptuous of its clientele …. Its very autonomy has led to insularity and a mistaken arrogance about its mission in the world… [and] … [to] … sanctimonious myths of the inherently superior qualities of themselves as professionals – of their knowledge and their work.”

Eliot Freidson 1970 (pages 369–370)

Freidson’s analyses helped to launch an extensive debate within sociology about the nature of profession and, in particular, whether medicine was losing or maintaining its professional powers and prerogatives (Hafferty, 1988). Like Freidson, Starr adopted a critical view of medicine by documenting medicine’s potential for both self-interest and self-deception—something perfectly captured in the evocative opening sentence of The Social Transformation of American Medicine—“The dream of reason did not take power into account” (Starr, 1984). Starr also saw medicine as initially successful in efforts to resist corporate control, but that success waned over time in the face of an omnivorous march by corporate forces.

Unless there is a radical turnabout in economic conditions and American politics, the last decades of the twentieth century are likely to be a time of diminished resources and autonomy for many physicians, voluntary hospitals, and medical schools … [with the] … rise of corporate enterprise in health services, which is already having a profound impact on the ethics and politics of medical care as well as its institutions.

Paul Starr 1984 (pages 420–421)

Sociologists, particularly Freidson and Starr, gained the attention of medical readers and highlighted the challenge to medicine as a profession about whose interests came first—the public or the physicians. The public might well have started to question whether the profession could be trusted.

Attention to issues of professionalism (as opposed to profession) has a similar, but more contemporary history. One early article entitled, “Culture and professionalism in education,” was authored by the famous educationalist and philosopher John Dewey (1923). However, articles on professionalism were few and far between during most of the 1900s, and very few focused on medicine. Aside from one article each in the nursing, hospital administration, and pharmacy literatures, it would not be until the early 1990s before a reasonable substantive (more than 20 citations) professionalism literature began to take shape within medicine. The first three of these articles were, “Yellow professionalism. Advertising by physicians in the yellow pages,”published in the The New England Journal of Medicine (Reade, 1987) and, “Countdown to millennium: balancing the professionalism and business of medicine: medicine’s rocking horse,” published in The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) (Lundberg, 1990), and, “Conflicts of interest: physician ownership of medical facilities,” also published in JAMA (Clarke et al, 1992).

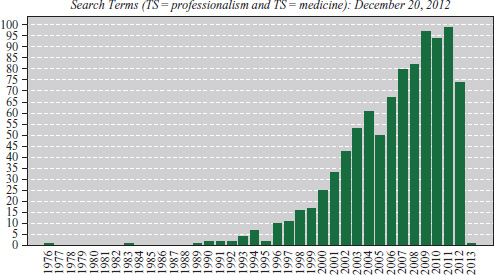

These three exemplars notwithstanding, professionalism articles within medicine would remain scanty for much of the 1990s. Figure 3-1, compiled from Web of Science data, traces the publication of articles on professionalism since the early 1970s and illustrates that a substantive literature using the word “professionalism” did not emerge until the late 1990 to early 2000s.

This historical window into the rise of a professionalism literature within medicine highlights several important points. First, this publication-centric view helps us to date the rise of a professionalism movement within medicine to the turn of the twenty-first century. In other words, the movement, at best, is no more than 25 years old. In fact there were other terms being used to describe problems including communication difficulties, student attitudes of cynicism, and ethical problems, but they were not gathered under the umbrella of “professionalism.”

Second, there have been shifts over time in the kinds of topics or issues addressed under the banner of professionalism. The three articles mentioned focus on advertising, the relationship of commercialism and medicine, and conflicts-of-interest, respectively. Other “professionalism issues,” such as duty hours and social media, did not appear until 2000.

Third, issues of professionalism reflect political and economic environments (Hafferty & McKinlay, 1993). It is not surprising to see the theme of commercialism and conflict of interest in medicine as a key issue in these U.S. publications, since the “business” side of medicine was emerging as a strong influence. The idea of dual agency, that is, working for the public interests versus the interest of the profession, did not have the same resonance within a U.K., Canadian, or German healthcare environment, where the “business” side of medicine was less evident.

THE MOVEMENT: OPENING SALVOS

Medicine’s modern day professionalism movement was well underway by the late 1990s. Editorials began to address the threats of commercialism to values of professionalism. Articles emerged about the medical-industrial complex (Relman, 1980) and the rise of for-profit medicine; “big business” could be antithetical to professional ideals. What followed was a flurry of calls, first to define professionalism, given the widely circulating observation that the medical community lacked a definitional consensus (Swick, 2000); then to teach professionalism principles to trainees, given the emerging conclusion that the best route to salvation would come via the newest generation of providers (Swick et al, 1999); and finally to measure and assess professionalism, given the widely circulating belief that any efforts to pass on these “new” ideals to trainees would be futile unless assessment was part of the package (Lynch, Surdyk, & Eiser, 2004). In turn, there was a variety of efforts to institutionalize professionalism within medical settings with the creation of professionalism codes, charters, curriculum, and competencies (Hafferty & Levinson, 2008).

The development of the professionalism movement was not linear. Although it is true that calls for definitions preceded calls for curricula or assessment, it also is true that assessment efforts have come to function as implicit definitions of professionalism and that the establishment of codes, charters, and competencies have spilled “backward” into the creation of new definitions. For these reasons, it is more accurate to think of professionalism pulses or waves—each having its moment, only to be recycled and renewed in some other form within a dynamic of interdependent and continuously evolving profiles. Table 3-1 lists examples of both early and more contemporary pulses.

|