EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient displays abdominal distention, quickly check for signs of hypovolemia, such as pallor, diaphoresis, hypotension, a rapid thready pulse, rapid shallow breathing, decreased urine output, and altered mentation. Ask the patient if he’s experiencing severe abdominal pain or difficulty breathing. Find out about any recent accidents, and observe him for signs of trauma and peritoneal bleeding, such as Cullen’s sign or Turner’s sign. Then, auscultate all abdominal quadrants, noting rapid and high-pitched, diminished, or absent bowel sounds. (If you don’t hear bowel sounds immediately, listen for at least 5 minutes in each of the four abdominal quadrants.) Gently palpate the abdomen for rigidity. Remember that deep or extensive palpation may increase pain.

If you detect abdominal distention and rigidity along with abnormal bowel sounds and if the patient complains of pain, begin emergency interventions. Place the patient in the supine position, administer oxygen, and insert an I.V. line for fluid replacement. Prepare to insert a nasogastric tube to relieve acute intraluminal distention. Reassure the patient, and prepare him for surgery.

History and Physical Examination

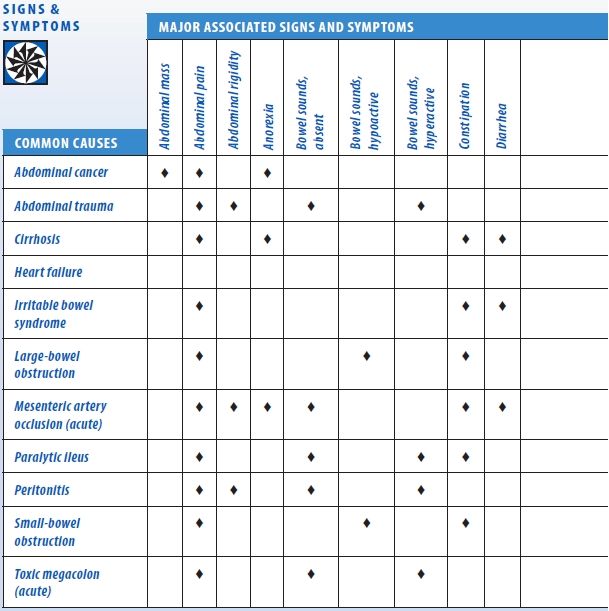

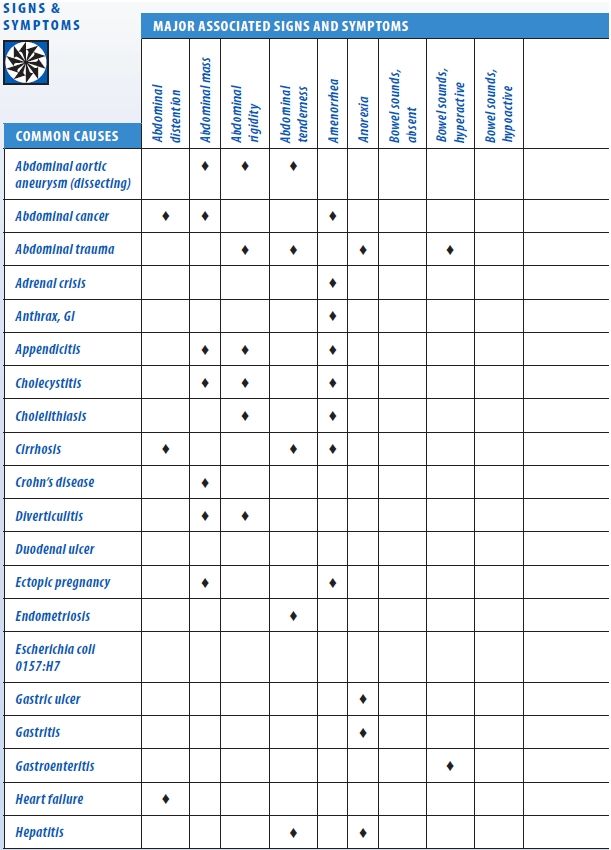

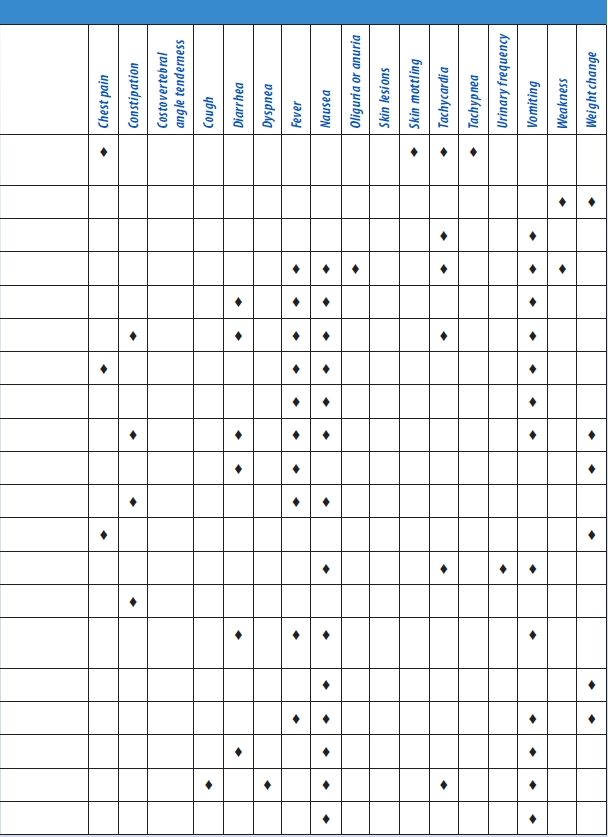

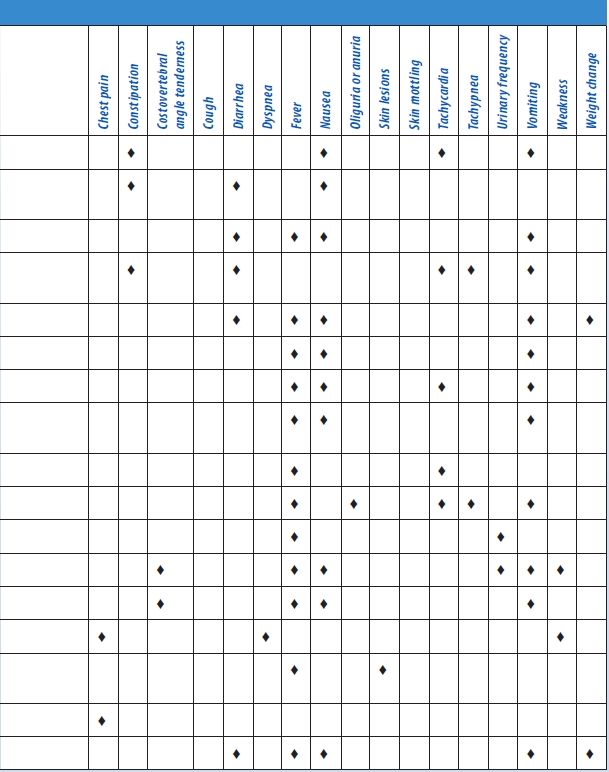

If the patient’s abdominal distention isn’t acute, ask about its onset and duration and associated signs. A patient with localized distention may report a sensation of pressure, fullness, or tenderness in the affected area. A patient with generalized distention may report a bloated feeling, a pounding heart, and difficulty breathing deeply or when lying flat. (See Abdominal Distention: Common Causes and Associated Findings.)

Abdominal Distention: Common Causes and Associated Findings

The patient may also feel unable to bend at his waist. Make sure to ask about abdominal pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, altered bowel habits, and weight gain or loss.

Obtain a medical history, noting GI or biliary disorders that may cause peritonitis or ascites, such as cirrhosis, hepatitis, or inflammatory bowel disease. (See Detecting Ascites, page 4.) Also, note chronic constipation. Has the patient recently had abdominal surgery, which can lead to abdominal distention? Ask about recent accidents, even minor ones, such as falling off a stepladder.

Perform a complete physical examination. Don’t restrict the examination to the abdomen because you could miss important clues to the cause of abdominal distention. Next, stand at the foot of the bed and observe the recumbent patient for abdominal asymmetry to determine if distention is localized or generalized. Then, assess abdominal contour by stooping at his side. Inspect for tense, taut skin and bulging flanks, which may indicate ascites. Observe the umbilicus. An everted umbilicus may indicate ascites or umbilical hernia. An inverted umbilicus may indicate distention from gas; it’s also common in obesity. Inspect the abdomen for signs of inguinal or femoral hernia and for incisions that may point to adhesions. Both may lead to intestinal obstruction. Then, auscultate for bowel sounds, abdominal friction rubs (indicating peritoneal inflammation), and bruits (indicating an aneurysm). Listen for succussion splash — a splashing sound normally heard in the stomach when the patient moves or when palpation disturbs the viscera. However, an abnormally loud splash indicates fluid accumulation, suggesting gastric dilation or obstruction.

EXAMINATION TIP Detecting Ascites

EXAMINATION TIP Detecting Ascites

To differentiate ascites from other causes of abdominal distention, check for shifting dullness, fluid wave, and puddle sign, as described here.

SHIFTING DULLNESS

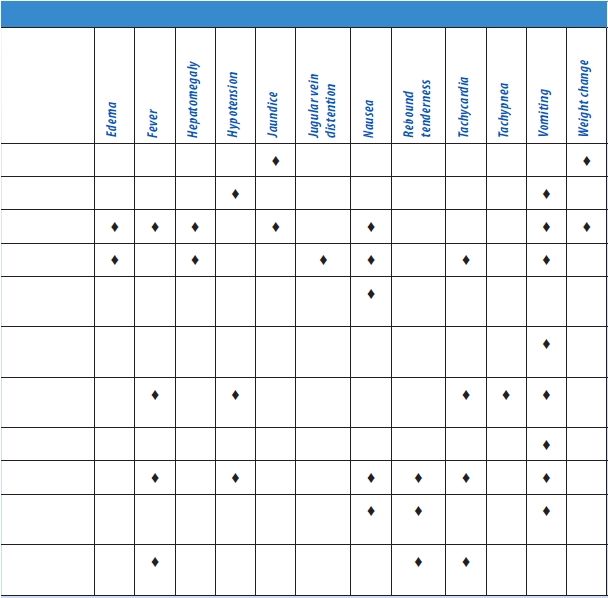

Step 1. With the patient in a supine position, percuss from the umbilicus outward to the flank, as shown. Draw a line on the patient’s skin to mark the change from tympany to dullness.

Step 2. Turn the patient onto his side. (Note that this positioning causes ascitic fluid to shift.) Percuss again, and mark the change from tympany to dullness. A difference between these lines can indicate ascites.

FLUID WAVE

Have another person press deeply into the patient’s midline to prevent vibration from traveling along the abdominal wall. Place one of your palms on one of the patient’s flanks. Strike the opposite flank with your other hand. If you feel the blow in the opposite palm, ascitic fluid is present.

PUDDLE SIGN

Position the patient on his elbows and knees, which causes ascitic fluid to pool in the most dependent part of the abdomen. Percuss the abdomen from the flank to the midline. The percussion note becomes louder at the edge of the puddle, or the ascitic pool.

Next, percuss and palpate the abdomen to determine if distention results from air, fluid, or both. A tympanic note in the left lower quadrant suggests an air-filled descending or sigmoid colon. A tympanic note throughout a generally distended abdomen suggests an air-filled peritoneal cavity. A dull percussion note throughout a generally distended abdomen suggests a fluid-filled peritoneal cavity. Shifting of dullness laterally with the patient in the decubitus position also indicates a fluid-filled abdominal cavity. A pelvic or intra-abdominal mass causes local dullness upon percussion and should be palpable. Obesity causes a large abdomen without shifting dullness, prominent tympany, or palpable bowel or other masses, with generalized rather than localized dullness.

Palpate the abdomen for tenderness, noting whether it’s localized or generalized. Watch for peritoneal signs and symptoms, such as rebound tenderness, guarding, rigidity, McBurney’s point, obturator sign, and psoas sign. Female patients should undergo a pelvic examination and males, a genital examination. All patients who report abdominal pain should undergo a digital rectal examination with fecal occult blood testing. Finally, measure the patient’s abdominal girth for a baseline value. Mark the flanks with a felt-tipped pen as a reference for subsequent measurements.

Medical Causes

- Abdominal cancer. Generalized abdominal distention may occur when the cancer — most commonly ovarian, hepatic, or pancreatic — produces ascites (usually in a patient with a known tumor). It’s an indication of advanced disease. Shifting dullness and a fluid wave accompany distention. Associated signs and symptoms may include severe abdominal pain, an abdominal mass, anorexia, jaundice, GI hemorrhage (hematemesis or melena), dyspepsia, and weight loss that progresses to muscle weakness and atrophy.

- Abdominal trauma. When brisk internal bleeding accompanies trauma, abdominal distention may be acute and dramatic. Associated signs and symptoms of this life-threatening disorder include abdominal rigidity with guarding, decreased or absent bowel sounds, vomiting, tenderness, and abdominal bruising. Pain may occur over the trauma site or over the scapula if abdominal bleeding irritates the phrenic nerve. Signs of hypovolemic shock (such as hypotension and rapid, thready pulse) appear with significant blood loss.

- Cirrhosis. In cirrhosis, ascites causes generalized distention and is confirmed by a fluid wave, shifting dullness, and a puddle sign. Umbilical eversion and caput medusae (dilated veins around the umbilicus) are common. The patient may report a feeling of fullness or weight gain. Associated findings include vague abdominal pain, fever, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, constipation or diarrhea, bleeding tendencies, severe pruritus, palmar erythema, spider angiomas, leg edema, and possibly splenomegaly. Hematemesis, encephalopathy, gynecomastia, or testicular atrophy may also be seen. Jaundice is usually a late sign. Hepatomegaly occurs initially, but the liver may not be palpable if the patient has advanced disease.

- Heart failure. Generalized abdominal distention due to ascites typically accompanies severe cardiovascular impairment and is confirmed by shifting dullness and a fluid wave. Signs and symptoms of heart failure are numerous and depend on the disease stage and degree of cardiovascular impairment. Hallmarks include peripheral edema, jugular vein distention, dyspnea, and tachycardia. Common associated signs and symptoms include hepatomegaly (which may cause right upper quadrant pain), nausea, vomiting, a productive cough, crackles, cool extremities, cyanotic nail beds, nocturia, exercise intolerance, nocturnal wheezing, diastolic hypertension, and cardiomegaly.

- Irritable bowel syndrome. Irritable bowel syndrome may produce intermittent, localized distention — the result of periodic intestinal spasms. Lower abdominal pain or cramping typically accompanies these spasms. The pain is usually relieved by defecation or by passage of intestinal gas and is aggravated by stress. Other possible signs and symptoms include diarrhea that may alternate with constipation or normal bowel function, nausea, dyspepsia, straining and urgency at defecation, a feeling of incomplete evacuation, and small, mucus-streaked stools.

- Large-bowel obstruction. Dramatic abdominal distention is characteristic in this life-threatening disorder; in fact, loops of the large bowel may become visible on the abdomen. Constipation precedes distention and may be the only symptom for days. Associated findings include tympany, high-pitched bowel sounds, and the sudden onset of colicky lower abdominal pain that becomes persistent. Fecal vomiting and diminished peristaltic waves and bowel sounds are late signs.

- Mesenteric artery occlusion (acute). In this life-threatening disorder, abdominal distention usually occurs several hours after the sudden onset of severe, colicky periumbilical pain accompanied by rapid (even forceful) bowel evacuation. The pain later becomes constant and diffuse. Related signs and symptoms include severe abdominal tenderness with guarding and rigidity, absent bowel sounds and, occasionally, a bruit in the right iliac fossa. The patient may also experience vomiting, anorexia, diarrhea, or constipation. Late signs include fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, and cool, clammy skin. Abdominal distention or GI bleeding may be the only clue if pain is absent.

- Paralytic ileus. Paralytic ileus, which produces generalized distention with a tympanic percussion note, is accompanied by absent or hypoactive bowel sounds and, occasionally, mild abdominal pain and vomiting. The patient may be severely constipated or may pass flatus and small, liquid stools.

- Peritonitis. Peritonitis is a life-threatening disorder in which abdominal distention may be localized or generalized, depending on the extent of the inflammation. Fluid accumulates within the peritoneal cavity and then within the bowel lumen, causing a fluid wave and shifting dullness. Typically, distention is accompanied by sudden and severe abdominal pain that worsens with movement, rebound tenderness, and abdominal rigidity.

The skin over the patient’s abdomen may appear taut. Associated signs and symptoms usually include hypoactive or absent bowel sounds, fever, chills, hyperalgesia, nausea, and vomiting. Signs of shock, such as tachycardia and hypotension, appear with significant fluid loss into the abdomen.

- Small-bowel obstruction. Abdominal distention is characteristic in small-bowel obstruction, a life-threatening disorder, and is most pronounced during late obstruction, especially in the distal small bowel. Auscultation reveals hypoactive or hyperactive bowel sounds, whereas percussion produces a tympanic note. Accompanying signs and symptoms include colicky periumbilical pain, constipation, nausea, and vomiting; the higher the obstruction, the earlier and more severe the vomiting. Rebound tenderness reflects intestinal strangulation with ischemia. Associated signs and symptoms include drowsiness, malaise, and signs of dehydration. Signs of hypovolemic shock appear with progressive dehydration and plasma loss.

- Toxic megacolon (acute). Toxic megacolon is a life-threatening complication of infectious or ulcerative colitis. It produces dramatic abdominal distention that usually develops gradually and is accompanied by a tympanic percussion note, diminished or absent bowel sounds, and mild rebound tenderness. The patient also presents with abdominal pain and tenderness, fever, tachycardia, and dehydration.

Special Considerations

Position the patient comfortably, using pillows for support. Place him on his left side to help flatus escape. Or, if he has ascites, elevate the head of the bed to ease his breathing. Administer drugs to relieve pain, and offer emotional support.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as abdominal X-rays, endoscopy, laparoscopy, ultrasonography, computed tomography scan or, possibly, paracentesis.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient to use slow breathing to help relieve abdominal discomfort, and emphasize the importance of oral hygiene to prevent dry mouth. If the patient has an obstruction or ascites, tell him which foods and fluids to avoid.

Pediatric Pointers

Because a young child’s abdomen is normally rounded, distention may be difficult to observe. Fortunately, a child’s abdominal wall is less well developed than an adult’s, making palpation easier. When percussing the abdomen, remember that a child normally swallows air when eating and crying, resulting in louder-than-normal tympany. Minimal tympany with abdominal distention may result from fluid accumulation or solid masses. To check for abdominal fluid, test for shifting dullness instead of a fluid wave. (In a child, air swallowing and incomplete abdominal muscle development make the fluid wave difficult to interpret.)

Sometimes, a child won’t cooperate with a physical examination. Try to gain the child’s confidence, and consider allowing him to remain in the parent’s or caregiver’s lap. You can gather clues by observing the child while he’s coughing, walking, or even climbing on office furniture. Remove all the child’s clothing to avoid missing diagnostic clues. Also, perform a gentle rectal examination.

In neonates, ascites usually result from GI or urinary perforation; in older children, from heart failure, cirrhosis, or nephrosis. Besides ascites, congenital malformations of the GI tract (such as intussusception and volvulus) may cause abdominal distention. A hernia may cause distention if it produces an intestinal obstruction. In addition, overeating and constipation can cause distention.

Geriatric Pointers

As people age, fat tends to accumulate in the lower abdomen and near the hips, even when body weight is stable. This accumulation, together with weakening abdominal muscles, commonly produces a potbelly, which some elderly patients interpret as fluid collection or evidence of disease.

REFERENCES

Bebars, G. (2011). Shock, mental status deterioration, and abdominal distention in an elderly man. Medscape, January 14, 2011.

Sanders, M., & Gunn-Sanders, A. (2011). Insidious abdominal symptoms with urinary disturbances. Medscape, September 2011.

Abdominal Mass

(See Also Abdominal Distention, Abdominal Pain, Abdominal Rigidity)

Commonly detected on routine physical examination, an abdominal mass is a localized swelling in one abdominal quadrant. Typically, this sign develops insidiously and may represent an enlarged organ, a neoplasm, an abscess, a vascular defect, or a fecal mass.

Distinguishing an abdominal mass from a normal structure requires skillful palpation. At times, palpation must be repeated with the patient in a different position or performed by a second examiner to verify initial findings. A palpable abdominal mass is an important clinical sign and usually represents a serious — and perhaps life-threatening — disorder.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient has a pulsating midabdominal mass and severe abdominal or back pain, suspect an aortic aneurysm. Quickly take his vital signs. Because the patient may require emergency surgery, withhold food or fluids until he’s examined. Prepare to administer oxygen and to start an I.V. infusion for fluid and blood replacement. Obtain routine preoperative tests, and prepare the patient for angiography. Frequently monitor blood pressure, pulse, respirations, and urine output.

Be alert for signs of shock, such as tachycardia, hypotension, and cool clammy skin, which may indicate significant blood loss.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient’s abdominal mass doesn’t suggest an aortic aneurysm, continue with a detailed history. Ask the patient if the mass is painful. If so, ask if the pain is constant or if it occurs only on palpation. Is it localized or generalized? Determine if the patient was already aware of the mass. If he was, find out if he noticed any change in the size or location of the mass.

Next, review the patient’s medical history, paying special attention to GI disorders. Ask the patient about GI symptoms, such as constipation, diarrhea, rectal bleeding, abnormally colored stools, and vomiting. Has the patient noticed a change in his appetite? If the patient is female, ask whether her menstrual cycles are regular and when the first day of her last menstrual period was.

A complete physical examination should be performed. Next, auscultate for bowel sounds in each quadrant. Listen for bruits or friction rubs, and check for enlarged veins. Lightly palpate and then deeply palpate the abdomen, assessing any painful or suspicious areas last. Note the patient’s position when you locate the mass. Some masses can be detected only with the patient in a supine position; others require a sidelying position.

Estimate the size of the mass in centimeters. Determine its shape. Is it round or sausage shaped? Describe its contour as smooth, rough, sharply defined, nodular, or irregular. Determine the consistency of the mass. Is it doughy, soft, solid, or hard? Also, percuss the mass. A dull sound indicates a fluid-filled mass and a tympanic sound, an air-filled mass.

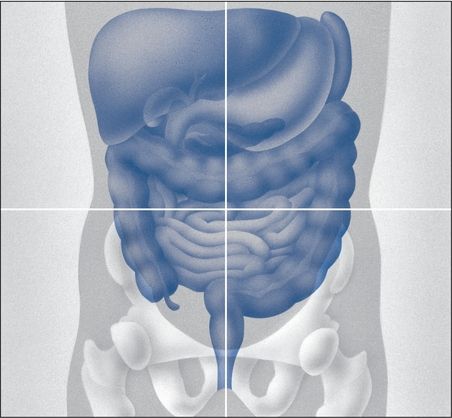

Next, determine if the mass moves with your hand or in response to respiration. Is the mass free-floating or attached to intra-abdominal structures? To determine whether the mass is located in the abdominal wall or the abdominal cavity, ask the patient to lift his head and shoulders off the examination table, thereby contracting his abdominal muscles. While these muscles are contracted, try to palpate the mass. If you can, the mass is in the abdominal wall; if you can’t, the mass is within the abdominal cavity. (See Abdominal Masses: Locations and Common Causes, page 10.)

After the abdominal examination is complete, perform pelvic, genital, and rectal examinations.

Medical Causes

- Abdominal aortic aneurysm. Abdominal aortic aneurysm may persist for years, producing only a pulsating periumbilical mass with a systolic bruit over the aorta. However, it may become life threatening if the aneurysm expands and its walls weaken. In such cases, the patient initially reports constant upper abdominal pain or, less commonly, low back or dull abdominal pain. If the aneurysm ruptures, he’ll report severe abdominal and back pain. After rupture, the aneurysm no longer pulsates.

Associated signs and symptoms of rupture include mottled skin below the waist, absent femoral and pedal pulses, lower blood pressure in the legs than in the arms, mild to moderate tenderness with guarding, and abdominal rigidity. Signs of shock — such as tachycardia and cool, clammy skin — appear with significant blood loss.

Abdominal Masses: Locations and Common Causes

The location of an abdominal mass provides an important clue to the causative disorder. Here are the disorders most commonly responsible for abdominal masses in each of the four abdominal quadrants.

RIGHT UPPER QUADRANT

- Aortic aneurysm (epigastric area)

- Cholecystitis or cholelithiasis

- Gallbladder, gastric, or hepatic carcinoma

- Hepatomegaly

- Hernia (incisional or umbilical)

- Hydronephrosis

- Pancreatic abscess or pseudocysts

- Renal cell carcinoma

RIGHT LOWER QUADRANT

- Bladder distention (suprapubic area)

- Colon cancer

- Crohn’s disease

- Hernia (incisional or inguinal)

- Ovarian cyst (suprapubic area)

- Uterine leiomyomas (suprapubic area)

LEFT UPPER QUADRANT

- Aortic aneurysm (epigastric area)

- Gastric carcinoma (epigastric area)

- Hernia (incisional or umbilical)

- Hydronephrosis

- Pancreatic abscess (epigastric area)

- Pancreatic pseudocysts (epigastric area)

- Renal cell carcinoma

- Splenomegaly

LEFT LOWER QUADRANT

- Bladder distention (suprapubic area)

- Colon cancer

- Diverticulitis

- Hernia (incisional or inguinal)

- Ovarian cyst (suprapubic area)

- Uterine leiomyomas (suprapubic area)

- Volvulus

- Cholecystitis. Deep palpation below the liver border may reveal a smooth, firm, sausage-shaped mass. However, with acute inflammation, the gallbladder is usually too tender to be palpated. Cholecystitis can cause severe right upper quadrant pain that may radiate to the right shoulder, chest, or back; abdominal rigidity and tenderness; fever; pallor; diaphoresis; anorexia; nausea; and vomiting. Recurrent attacks usually occur 1 to 6 hours after meals. Murphy’s sign (inspiratory arrest elicited when the examiner palpates the right upper quadrant as the patient takes a deep breath) is common.

- Colon cancer. A right lower quadrant mass may occur with cancer of the right colon, which may also cause occult bleeding with anemia and abdominal aching, pressure, or dull cramps. Associated findings include weakness, fatigue, exertional dyspnea, vertigo, and signs and symptoms of intestinal obstruction, such as obstipation and vomiting.

Occasionally, cancer of the left colon also causes a palpable mass. It usually produces rectal bleeding, intermittent abdominal fullness or cramping, and rectal pressure. The patient may also report fremitus and pelvic discomfort. Later, he develops obstipation; diarrhea; or pencil-shaped, grossly bloody, or mucus-streaked stools. Typically, defecation relieves pain.

- Crohn’s disease. With Crohn’s disease, tender, sausage-shaped masses are usually palpable in the right lower quadrant and, at times, in the left lower quadrant. Attacks of colicky right lower quadrant pain and diarrhea are common. Associated signs and symptoms include fever, anorexia, weight loss, hyperactive bowel sounds, nausea, abdominal tenderness with guarding, and perirectal, skin, or vaginal fistulas.

- Diverticulitis. Most common in the sigmoid colon, diverticulitis may produce a left lower quadrant mass that’s usually tender, firm, and fixed. It also produces intermittent abdominal pain that’s relieved by defecation or passage of flatus. Other findings may include alternating constipation and diarrhea, nausea, a low-grade fever, and a distended and tympanic abdomen.

- Gastric cancer. Advanced gastric cancer may produce an epigastric mass. Early findings include chronic dyspepsia and epigastric discomfort, whereas late findings include weight loss, a feeling of fullness after eating, fatigue and, occasionally, coffee-ground vomitus or melena.

- Hepatomegaly. Hepatomegaly produces a firm, blunt, irregular mass in the epigastric region or below the right costal margin. Associated signs and symptoms vary with the causative disorder but commonly include ascites, right upper quadrant pain and tenderness, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, leg edema, jaundice, palmar erythema, spider angiomas, gynecomastia, testicular atrophy and, possibly, splenomegaly.

- Hernia. The soft and typically tender bulge is usually an effect of prolonged, increased intra-abdominal pressure on weakened areas of the abdominal wall. An umbilical hernia is typically located around the umbilicus and an inguinal hernia in either the right or left groin. An incisional hernia can occur anywhere along a previous incision. Hernia may be the only sign until strangulation occurs.

- Hydronephrosis. Enlarging one or both kidneys, hydronephrosis produces a smooth, boggy mass in one or both flanks. Other findings vary with the degree of hydronephrosis. The patient may have severe colicky renal pain or dull flank pain that radiates to the groin, vulva, or testes. Hematuria, pyuria, dysuria, alternating oliguria and polyuria, nocturia, accelerated hypertension, nausea, and vomiting may also occur.

- Ovarian cyst. A large ovarian cyst may produce a smooth, rounded, fluctuant mass, resembling a distended bladder, in the suprapubic region. Large or multiple cysts may also cause mild pelvic discomfort, low back pain, menstrual irregularities, and hirsutism. A twisted or ruptured cyst may cause abdominal tenderness, distention, and rigidity.

- Splenomegaly. The lymphomas, leukemias, hemolytic anemias, and inflammatory diseases are among the many disorders that may cause splenomegaly. Typically, the smooth edge of the enlarged spleen is palpable in the left upper quadrant. Associated signs and symptoms vary with the causative disorder but usually include a feeling of abdominal fullness, left upper quadrant abdominal pain and tenderness, splenic friction rub, splenic bruits, and a low-grade fever.

- Uterine leiomyomas (fibroids). If large enough, these common, benign uterine tumors produce a round, multinodular mass in the suprapubic region. The patient’s chief complaint is usually menorrhagia; she may also experience a feeling of heaviness in the abdomen, and pressure on surrounding organs may cause back pain, constipation, and urinary frequency or urgency. Edema and varicosities of the lower extremities may develop. Rapid fibroid growth in perimenopausal or postmenopausal women needs further evaluation.

Special Considerations

Discovery of an abdominal mass commonly causes anxiety. Offer emotional support to the patient and his family as they await the diagnosis. Position the patient comfortably, and administer drugs for pain or anxiety as needed.

If an abdominal mass causes bowel obstruction, watch for indications of peritonitis — abdominal pain and rebound tenderness — and for signs of shock, such as tachycardia and hypotension.

Patient Counseling

Explain any diagnostic tests that are needed, and teach the patient about the cause of the abdominal mass once a diagnosis is made. Explain treatment and potential outcomes.

Pediatric Pointers

Detecting an abdominal mass in an infant can be quite a challenge. However, these tips will make palpation easier for you: Allow an infant to suck on his bottle or pacifier to prevent crying, which causes abdominal rigidity and interferes with palpation. Avoid tickling him because laughter also causes abdominal rigidity. Also, reduce his apprehension by distracting him with cheerful conversation. Rest your hand on his abdomen for a few moments before palpation. If he remains sensitive, place his hand under yours as you palpate. Consider allowing the child to remain on the parent’s or caregiver’s lap. A gentle rectal examination should also be performed.

In neonates, most abdominal masses result from renal disorders, such as polycystic kidney disease or congenital hydronephrosis. In older infants and children, abdominal masses usually are caused by enlarged organs, such as the liver and spleen.

Other common causes include Wilms’ tumor, neuroblastoma, intussusception, volvulus, Hirschsprung’s disease (congenital megacolon), pyloric stenosis, and abdominal abscess.

Geriatric Pointers

Ultrasonography should be used to evaluate a prominent midepigastric mass in thin, elderly patients.

REFERENCES

Dultz, L., Vivar, K., MacFarland, S., & Hopkins, M. (2011). An abdominal mass with related premenstrual pain. Medscape, June 02, 2011.

Gourgiotis, S., Veloudis, G., Pallas, N., Lagos P., Salemis N. S., & Villias C. (2008). Abdominal wall endometriosis: Report of two cases. Romanian Journal of Morphology and Embryology, l49(4), 553–555.

Abdominal Pain

(See Also Abdominal Distention, Abdominal Mass, Abdominal Rigidity)

Abdominal pain usually results from a GI disorder, but it can be caused by a reproductive, genitourinary (GU), musculoskeletal, or vascular disorder; drug use; or ingestion of toxins. At times, such pain signals life-threatening complications.

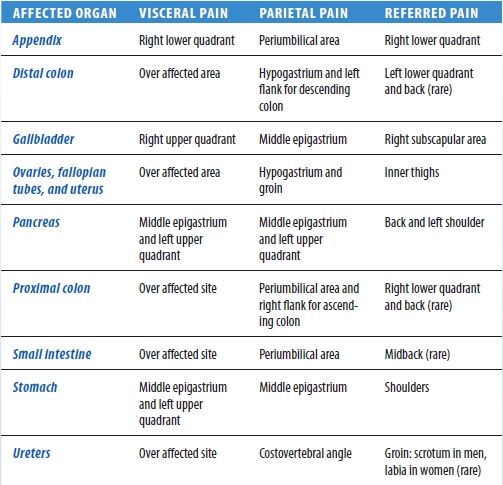

Abdominal pain arises from the abdominopelvic viscera, the parietal peritoneum, or the capsules of the liver, kidney, or spleen. It may be acute or chronic and diffuse or localized. Visceral pain develops slowly into a deep, dull, aching pain that’s poorly localized in the epigastric, periumbilical, or lower midabdominal (hypogastric) region. In contrast, somatic (parietal, peritoneal) pain produces a sharp, more intense, and well-localized discomfort that rapidly follows the insult. Movement or coughing aggravates this pain. (See Abdominal Pain: Types and Locations.)

Abdominal Pain: Types and Locations

Pain may also be referred to the abdomen from another site with the same or similar nerve supply. This sharp, well-localized, referred pain is felt in skin or deeper tissues and may coexist with skin hyperesthesia and muscle hyperalgesia.

Mechanisms that produce abdominal pain include stretching or tension of the gut wall, traction on the peritoneum or mesentery, vigorous intestinal contraction, inflammation, ischemia, and sensory nerve irritation.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient is experiencing sudden and severe abdominal pain, quickly take his vital signs and palpate pulses below the waist. Be alert for signs of hypovolemic shock, such as tachycardia and hypotension. Obtain I.V. access.

Emergency surgery may be required if the patient also has mottled skin below the waist and a pulsating epigastric mass or rebound tenderness and rigidity.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient has no life-threatening signs or symptoms, take his history. Ask him if he has had this type of pain before. Have him describe the pain — for example dull, sharp, stabbing, or burning. Ask if anything relieves the pain or makes it worse. Ask the patient if the pain is constant or intermittent and when the pain began. Constant, steady abdominal pain suggests organ perforation, ischemia, or inflammation or blood in the peritoneal cavity. Intermittent, cramping abdominal pain suggests that the patient may have obstruction of a hollow organ.

If pain is intermittent, find out the duration of a typical episode. In addition, ask the patient where the pain is located and if it radiates to other areas.

Find out if movement, coughing, exertion, vomiting, eating, elimination, or walking worsens or relieves the pain. The patient may report abdominal pain as indigestion or gas pain, so have him describe it in detail.

Ask the patient about substance abuse and any history of vascular, GI, GU, or reproductive disorders. Ask the female patient about the date of her last period, changes in her menstrual pattern, or dyspareunia.

Ask the patient about appetite changes. Ask about the onset and frequency of nausea or vomiting. Find out about increased flatulence, constipation, diarrhea, and changes in stool consistency. When was the last bowel movement? Ask about urinary frequency, urgency, or pain. Is the urine cloudy or pink?

Perform a physical examination. Take the patient’s vital signs, and assess skin turgor and mucous membranes. Inspect his abdomen for distention or visible peristaltic waves and, if indicated, measure his abdominal girth.

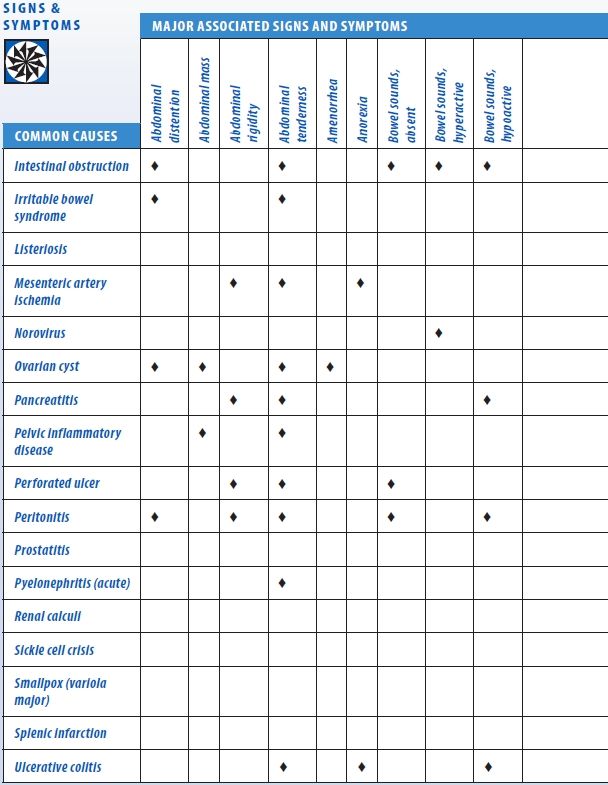

Auscultate for bowel sounds, and characterize their motility. Percuss all quadrants, noting the percussion sounds. Palpate the entire abdomen for masses, rigidity, and tenderness. Check for costovertebral angle (CVA) tenderness, abdominal tenderness with guarding, and rebound tenderness. (See Abdominal Pain: Common Causes and Associated Findings, pages 16 to 19.)

Medical Causes

- Abdominal aortic aneurysm (dissecting). Initially, this life-threatening disorder may produce dull lower abdominal, lower back, or severe chest pain. Usually, abdominal aortic aneurysm produces constant upper abdominal pain, which may worsen when the patient lies down and may abate when he leans forward or sits up. Palpation may reveal an epigastric mass that pulsates before rupture but not after it.

Other findings may include mottled skin below the waist, absent femoral and pedal pulses, lower blood pressure in the legs than in the arms, mild to moderate abdominal tenderness with guarding, and abdominal rigidity. Signs of shock, such as tachycardia and tachypnea, may appear.

- Abdominal cancer. Abdominal pain usually occurs late in abdominal cancer. It may be accompanied by anorexia, weight loss, weakness, depression, and abdominal mass and distention.

- Abdominal trauma. Generalized or localized abdominal pain occurs with ecchymoses on the abdomen, abdominal tenderness, vomiting and, with hemorrhage into the peritoneal cavity, abdominal rigidity. Bowel sounds are decreased or absent. The patient may have signs of hypovolemic shock, such as hypotension and a rapid, thready pulse.

- Adrenal crisis. Severe abdominal pain appears early, along with nausea, vomiting, dehydration, profound weakness, anorexia, and fever. Later signs are progressive loss of consciousness; hypotension; tachycardia; oliguria; cool, clammy skin; and increased motor activity, which may progress to delirium or seizures.

Abdominal Pain: Common Causes and Associated Findings

- Anthrax, GI. An acute infectious disease, GI anthrax is caused by the gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium Bacillus anthracis. Although the disease most commonly occurs in wild and domestic grazing animals, such as cattle, sheep, and goats, the spores can live in the soil for many years. The disease can occur in humans exposed to infected animals, tissue from infected animals, or biological warfare. Most natural cases occur in agricultural regions worldwide. Anthrax may occur in any of the following forms: cutaneous, inhaled, or GI.

GI anthrax is caused by eating contaminated meat from an infected animal. Initial signs and symptoms include loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, and fever. Late signs and symptoms include abdominal pain, severe bloody diarrhea, and hematemesis.

- Appendicitis. With appendicitis, a life-threatening disorder, pain initially occurs in the epigastric or umbilical region. Anorexia, nausea, or vomiting may occur after the onset of pain. Pain localizes at McBurney’s point in the right lower quadrant and is accompanied by abdominal rigidity, increasing tenderness (especially over McBurney’s point), rebound tenderness, and retractive respirations. Later signs and symptoms include malaise, constipation (or diarrhea), low-grade fever, and tachycardia.

- Cholecystitis. Severe pain in the right upper quadrant may arise suddenly or increase gradually over several hours, usually after meals. It may radiate to the right shoulder, chest, or back. Accompanying the pain are anorexia, nausea, vomiting, fever, abdominal rigidity, tenderness, pallor, and diaphoresis. Murphy’s sign (inspiratory arrest elicited when the examiner palpates the right upper quadrant as the patient takes a deep breath) is common.

- Cholelithiasis. Patients may suffer sudden, severe, and paroxysmal pain in the right upper quadrant lasting several minutes to several hours. The pain may radiate to the epigastrium, back, or shoulder blades. The pain is accompanied by anorexia, nausea, vomiting (sometimes bilious), diaphoresis, restlessness, and abdominal tenderness with guarding over the gallbladder or biliary duct. The patient may also experience fatty food intolerance and frequent indigestion.

- Cirrhosis. Dull abdominal aching occurs early and is usually accompanied by anorexia, indigestion, nausea, vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea. Subsequent right upper quadrant pain worsens when the patient sits up or leans forward. Associated signs include fever, ascites, leg edema, weight gain, hepatomegaly, jaundice, severe pruritus, bleeding tendencies, palmar erythema, and spider angiomas. Gynecomastia and testicular atrophy may also be present.

- Crohn’s disease. An acute attack in Crohn’s disease causes severe cramping pain in the lower abdomen, typically preceded by weeks or months of milder cramping pain. Crohn’s disease may also cause diarrhea, hyperactive bowel sounds, dehydration, weight loss, fever, abdominal tenderness with guarding, and possibly a palpable mass in a lower quadrant. Abdominal pain is commonly relieved by defecation. Milder chronic signs and symptoms include right lower quadrant pain with diarrhea, steatorrhea, and weight loss. Complications include perirectal or vaginal fistulas.

- Diverticulitis. Mild cases of diverticulitis usually produce intermittent, diffuse left lower quadrant pain, which is sometimes relieved by defecation or passage of flatus and worsened by eating. Other signs and symptoms include nausea, constipation or diarrhea, a low-grade fever and, in many cases, a palpable abdominal mass that’s usually tender, firm, and fixed. Rupture causes severe left lower quadrant pain, abdominal rigidity and, possibly, signs and symptoms of sepsis and shock (high fever, chills, and hypotension).

- Duodenal ulcer. Localized abdominal pain — described as steady, gnawing, burning, aching, or hunger-like — may occur high in the midepigastrium, slightly off center, usually on the right. The pain usually doesn’t radiate unless pancreatic penetration occurs. It typically begins 2 to 4 hours after a meal and may cause nocturnal awakening. Ingestion of food or antacids brings relief until the cycle starts again, but it may also produce weight gain. Other symptoms include changes in bowel habits and heartburn or retrosternal burning.

- Ectopic pregnancy. Lower abdominal pain may be sharp, dull, or cramping and constant or intermittent in ectopic pregnancy, a potentially life-threatening disorder. Vaginal bleeding, nausea, and vomiting may occur, along with urinary frequency, a tender adnexal mass, and a 1- to 2-month history of amenorrhea. Rupture of the fallopian tube produces sharp lower abdominal pain, which may radiate to the shoulders and neck and become extreme with cervical or adnexal palpation. Signs of shock (such as pallor, tachycardia, and hypotension) may also appear.

- Endometriosis. Constant, severe pain in the lower abdomen usually begins 5 to 7 days before the start of menses and may be aggravated by defecation. Depending on the location of the ectopic tissue, the pain may be accompanied by constipation, abdominal tenderness, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and deep sacral pain.

- Escherichia coli O157:H7. E. coli O157:H7 is an aerobic, gram-negative bacillus that causes food-borne illness. Most strains of E. coli are harmless and are part of normal intestinal flora of healthy humans and animals. However, E. coli O157:H7, one of hundreds of strains of the bacterium, is capable of producing a powerful toxin and can cause severe illness. Eating undercooked beef or other foods contaminated with the bacteria causes the disease. Signs and symptoms include watery or bloody diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, fever, and abdominal cramps. In children younger than age 5 and in elderly patients, hemolytic-uremic syndrome may develop, and this may ultimately lead to acute renal failure.

- Gastric ulcer. Diffuse, gnawing, burning pain in the left upper quadrant or epigastric area commonly occurs 1 to 2 hours after meals and may be relieved by ingestion of food or antacids. Vague bloating and nausea after eating are common. Indigestion, weight change, anorexia, and episodes of GI bleeding also occur.

- Gastritis. With acute gastritis, the patient experiences a rapid onset of abdominal pain that can range from mild epigastric discomfort to burning pain in the left upper quadrant. Other typical features include belching, fever, malaise, anorexia, nausea, bloody or coffee-ground vomitus, and melena. However, significant bleeding is unusual, unless the patient has hemorrhagic gastritis.

- Gastroenteritis. Cramping or colicky abdominal pain, which can be diffuse, originates in the left upper quadrant and radiates or migrates to the other quadrants, usually in a peristaltic manner. It’s accompanied by diarrhea, hyperactive bowel sounds, headache, myalgia, nausea, and vomiting.

- Heart failure. Right upper quadrant pain commonly accompanies heart failure’s hallmarks: jugular vein distention, dyspnea, tachycardia, and peripheral edema. Other findings include nausea, vomiting, ascites, productive cough, crackles, cool extremities, and cyanotic nail beds. Clinical signs are numerous and vary according to the stage of the disease and amount of cardiovascular impairment.

- Hepatitis. Liver enlargement from any type of hepatitis causes discomfort or dull pain and tenderness in the right upper quadrant. Associated signs and symptoms may include dark urine, clay-colored stools, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, jaundice, malaise, and pruritus.

- Intestinal obstruction. Short episodes of intense, colicky, cramping pain alternate with pain-free intervals in an intestinal obstruction, a life-threatening disorder. Accompanying signs and symptoms may include abdominal distention, tenderness, and guarding; visible peristaltic waves; high-pitched, tinkling, or hyperactive sounds proximal to the obstruction and hypoactive or absent sounds distally; obstipation; and pain-induced agitation. In jejunal and duodenal obstruction, nausea and bilious vomiting occur early. In distal small- or large-bowel obstruction, nausea and vomiting are commonly feculent. Complete obstruction produces absent bowel sounds. Late-stage obstruction produces signs of hypovolemic shock, such as hypotension and tachycardia.

- Irritable bowel syndrome. Lower abdominal cramping or pain is aggravated by ingestion of coarse or raw foods and may be alleviated by defecation or passage of flatus. Related findings include abdominal tenderness, diurnal diarrhea alternating with constipation or normal bowel function, and small stools with visible mucus. Dyspepsia, nausea, and abdominal distention with a feeling of incomplete evacuation may also occur. Stress, anxiety, and emotional lability intensify the symptoms.

- Listeriosis. A serious infection, listeriosis is caused by eating food contaminated with the bacterium Listeria monocytogenes. This food-borne illness primarily affects pregnant women, neonates, and those with weakened immune systems. Signs and symptoms include fever, myalgia, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. If the infection spreads to the nervous system, meningitis may develop. Signs and symptoms include fever, headache, nuchal rigidity, and change in the level of consciousness.

GENDER CUE

GENDER CUE

Listeriosis infection during pregnancy may lead to premature delivery, infection of the neonate, or stillbirth.

- Mesenteric artery ischemia. Always suspect mesenteric artery ischemia in patients older than age 50 with chronic heart failure, cardiac arrhythmia, cardiovascular infarct, or hypotension who develop sudden, severe abdominal pain after 2 to 3 days of colicky periumbilical pain and diarrhea. Initially, the abdomen is soft and tender with decreased bowel sounds. Associated findings include vomiting, anorexia, alternating periods of diarrhea and constipation and, in late stages, extreme abdominal tenderness with rigidity, tachycardia, tachypnea, absent bowel sounds, and cool, clammy skin.

- Norovirus. The highly contagious Norovirus infection is transmitted by the fecal-oral route. An acute onset of GI irritation, with abdominal pain or cramping, occurs in patients affected with Noroviruses. Other symptoms include vomiting, uncontrolled stool seepage, watery nonbloody diarrhea, and nausea. Less common symptoms include low-grade fever, headache, chills, muscle aches, and generalized fatigue. Typically, Norovirus symptoms last from 1 to 5 days without lasting effects.

- Ovarian cyst. Torsion or hemorrhage causes pain and tenderness in the right or left lower quadrant. Sharp and severe if the patient suddenly stands or stoops, the pain becomes brief and intermittent if the torsion self-corrects or dull and diffuse after several hours if it doesn’t. Pain is accompanied by slight fever, mild nausea and vomiting, abdominal tenderness, a palpable abdominal mass and, possibly, amenorrhea. Abdominal distention may occur if the patient has a large cyst. Peritoneal irritation, or rupture and ensuing peritonitis, causes high fever and severe nausea and vomiting.

- Pancreatitis. Life-threatening acute pancreatitis produces fulminating, continuous upper abdominal pain that may radiate to both flanks and to the back. To relieve this pain, the patient may bend forward, draw his knees to his chest, or move restlessly about. Early findings include abdominal tenderness, nausea, vomiting, fever, pallor, tachycardia and, in some patients, abdominal rigidity, rebound tenderness, and hypoactive bowel sounds. Turner’s sign (ecchymosis of the abdomen or flank) or Cullen’s sign (a bluish tinge around the umbilicus) signals hemorrhagic pancreatitis. Jaundice may occur as inflammation subsides.

Chronic pancreatitis produces severe left upper quadrant or epigastric pain that radiates to the back. Abdominal tenderness, a midepigastric mass, jaundice, fever, and splenomegaly may occur. Steatorrhea, weight loss, maldigestion, and diabetes mellitus are common.

- Pelvic inflammatory disease. Pain in the right or left lower quadrant ranges from vague discomfort worsened by movement to deep, severe, and progressive pain. Sometimes, metrorrhagia precedes or accompanies the onset of pain. Extreme pain accompanies cervical or adnexal palpation. Associated findings include abdominal tenderness, a palpable abdominal or pelvic mass, fever, occasional chills, nausea, vomiting, urinary discomfort, and abnormal vaginal bleeding or purulent vaginal discharge.

- Perforated ulcer. With perforated ulcer, a life-threatening disorder, sudden, severe, and prostrating epigastric pain may radiate through the abdomen to the back or right shoulder. Other signs and symptoms include boardlike abdominal rigidity, tenderness with guarding, generalized rebound tenderness, absent bowel sounds, grunting and shallow respirations and, in many cases, fever, tachycardia, hypotension, and syncope.

- Peritonitis. With peritonitis, a life-threatening disorder, sudden and severe pain can be diffuse or localized in the area of the underlying disorder; movement worsens the pain. The degree of abdominal tenderness usually varies according to the extent of disease. Typical findings include fever; chills; nausea; vomiting; hypoactive or absent bowel sounds; abdominal tenderness, distention, and rigidity; rebound tenderness and guarding; hyperalgesia; tachycardia; hypotension; tachypnea; and positive psoas and obturator signs.

- Prostatitis. Vague abdominal pain or discomfort in the lower abdomen, groin, perineum, or rectum may develop with prostatitis. Other findings include dysuria, urinary frequency and urgency, fever, chills, low back pain, myalgia, arthralgia, and nocturia. Scrotal pain, penile pain, and pain on ejaculation may occur in chronic cases.

- Pyelonephritis (acute). Progressive lower quadrant pain in one or both sides, flank pain, and CVA tenderness characterize this disorder. Pain may radiate to the lower midabdomen or to the groin. Additional signs and symptoms include abdominal and back tenderness, high fever, shaking chills, nausea, vomiting, and urinary frequency and urgency.

- Renal calculi. Depending on the location of calculi, severe abdominal or back pain may occur. However, the classic symptom is severe, colicky pain that travels from the CVA to the flank, suprapubic region, and external genitalia. The pain may be excruciating or dull and constant. Pain-induced agitation, nausea, vomiting, abdominal distention, fever, chills, hypertension, and urinary urgency with hematuria and dysuria may occur.

- Sickle cell crisis. Sudden, severe abdominal pain may accompany chest, back, hand, or foot pain. Associated signs and symptoms include weakness, aching joints, dyspnea, and scleral jaundice.

- Smallpox (variola major). Worldwide eradication of smallpox was achieved in 1977; the United States and Russia have the only known storage sites for the virus. The virus is considered a potential agent for biological warfare. Initial signs and symptoms include high fever, malaise, prostration, severe headache, backache, and abdominal pain. A maculopapular rash develops on the mucosa of the mouth, pharynx, face, and forearms and then spreads to the trunk and legs. Within 2 days, the rash becomes vesicular and later pustular. The lesions develop at the same time, appear identical, and are more prominent on the face and extremities. The pustules are round, firm, and embedded in the skin. After 8 to 9 days, the pustules form a crust, and later, the scab separates from the skin, leaving a pitted scar. In fatal cases, death results from encephalitis, extensive bleeding, or secondary infection.

- Splenic infarction. Fulminating pain in the left upper quadrant occurs along with chest pain that may worsen on inspiration. Pain usually radiates to the left shoulder with splinting of the left diaphragm, abdominal guarding and, occasionally, a splenic friction rub.

- Ulcerative colitis. Ulcerative colitis may begin with vague abdominal discomfort that leads to cramping lower abdominal pain. As the disorder progresses, pain may become steady and diffuse, increasing with movement and coughing. The most common symptom — recurrent and possibly severe diarrhea with blood, pus, and mucus — may relieve the pain. The abdomen may feel soft, squashy, and extremely tender. High-pitched, infrequent bowel sounds may accompany nausea, vomiting, anorexia, weight loss, and mild, intermittent fever.

Other Causes

- Drugs. Salicylates and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs commonly cause burning, gnawing pain in the left upper quadrant or epigastric area, along with nausea and vomiting.

Special Considerations

Help the patient find a comfortable position to ease his distress. He should lie in a supine position, with his head flat on the table, arms at his sides, and knees slightly flexed to relax the abdominal muscles. Monitor him closely because abdominal pain can signal a life-threatening disorder. Especially important indications include tachycardia, hypotension, clammy skin, abdominal rigidity, rebound tenderness, a change in the pain’s location or intensity, or sudden relief from the pain.

Withhold analgesics from the patient because they may mask symptoms. Also withhold food and fluids because surgery may be needed. Prepare for I.V. infusion and insertion of a nasogastric or other intestinal tube. Peritoneal lavage or abdominal paracentesis may be required.

You may have to prepare the patient for a diagnostic procedure, which may include a pelvic and rectal examination; blood, urine, and stool tests; X-rays; barium studies; ultrasonography; endoscopy; and biopsy.

Patient Counseling

Explain the diagnostic tests the patient will need, which foods and fluids he shouldn’t have, the need to report any changes in bowel habits, and how to position himself to alleviate symptoms.

Pediatric Pointers

Because a child typically has difficulty describing abdominal pain, you should pay close attention to nonverbal cues, such as wincing, lethargy, or unusual positioning (such as a sidelying position with knees flexed to the abdomen). Observing the child while he coughs, walks, or climbs may offer some diagnostic clues. Also, remember that a parent’s description of the child’s complaints is a subjective interpretation of what the parent believes is wrong.

In children, abdominal pain can signal a disorder with greater severity or different associated signs than in adults. Appendicitis, for example, has higher rupture and mortality rates in children, and vomiting may be the only other sign. Acute pyelonephritis may cause abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea, but not the classic urologic signs found in adults. Peptic ulcer, which is becoming increasingly common in teenagers, causes nocturnal pain and colic that, unlike peptic ulcer in adults, may not be relieved by food.

Abdominal pain in children can also result from lactose intolerance, allergic-tension-fatigue syndrome, volvulus, Meckel’s diverticulum, intussusception, mesenteric adenitis, diabetes mellitus, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, and many uncommon disorders such as heavy metal poisoning. Remember, too, that a child’s complaint of abdominal pain may reflect an emotional need, such as a wish to avoid school or to gain adult attention.

Geriatric Pointers

Advanced age may decrease the manifestations of acute abdominal disease. Pain may be less severe, fever less pronounced, and signs of peritoneal inflammation diminished or absent.

REFERENCES

McCutcheon, T. (2013). The ileus and oddities after colorectal surgery. Gastroenterology Nursing, 36(5), 368–375.

Saccamano, S., & Ferrara, L. (2013). Evaluation of acute abdominal pain. The Nurse Practitioner: The American Journal of Primary Health Care, 38(11), 46–53.

Abdominal Rigidity

(See Also Abdominal Distention, Abdominal Mass, Abdominal Pain) [Abdominal muscle spasm, involuntary guarding]

Detected by palpation, abdominal rigidity refers to abnormal muscle tension or inflexibility of the abdomen. Rigidity may be voluntary or involuntary. Voluntary rigidity reflects the patient’s fear or nervousness upon palpation; involuntary rigidity reflects potentially life-threatening peritoneal irritation or inflammation. (See Recognizing Voluntary Rigidity, page 26.)

Involuntary rigidity most commonly results from GI disorders, but may also result from pulmonary and vascular disorders and from the effects of insect toxins. Usually, it’s accompanied by fever; nausea; vomiting; and abdominal tenderness, distention, and pain.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

After palpating abdominal rigidity, quickly take the patient’s vital signs. Even though the patient may not appear gravely ill or have markedly abnormal vital signs, abdominal rigidity calls for emergency interventions.

Prepare to administer oxygen and to insert an I.V. line for fluid and blood replacement. The patient may require drugs to support blood pressure. Also prepare him for catheterization, and monitor intake and output.

A nasogastric tube may have to be inserted to relieve abdominal distention. Because emergency surgery may be necessary, the patient should be prepared for laboratory tests and X-rays.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient’s condition allows further assessment, take a brief history. Find out when the abdominal rigidity began. Is it associated with abdominal pain? If so, did the pain begin at the same time? Determine whether the abdominal rigidity is localized or generalized. Is it always present? Has its site changed or remained constant? Next, ask about aggravating or alleviating factors, such as position changes, coughing, vomiting, elimination, and walking.

Explore other signs and symptoms. Inspect the abdomen for peristaltic waves, which may be visible in very thin patients. Also, check for a visibly distended bowel loop. Next, auscultate bowel sounds. Perform light palpation to locate the rigidity and determine its severity. Avoid deep palpation, which may exacerbate abdominal pain. Finally, check for poor skin turgor and dry mucous membranes, which indicate dehydration.

Medical Causes

- Abdominal aortic aneurysm (dissecting). Mild to moderate abdominal rigidity occurs with abdominal aortic aneurysm, a life-threatening disorder. Typically, it’s accompanied by constant upper abdominal pain that may radiate to the lower back. The pain may worsen when the patient lies down and may be relieved when he leans forward or sits up. Before rupture, the aneurysm may produce a pulsating mass in the epigastrium, accompanied by a systolic bruit over the aorta. However, the mass stops pulsating after rupture. Associated signs and symptoms include mottled skin below the waist, absent femoral and pedal pulses, lower blood pressure in the legs than in the arms, and mild to moderate tenderness with guarding. Significant blood loss causes signs of shock, such as tachycardia, tachypnea, and cool, clammy skin.

EXAMINATION TIP Recognizing Voluntary Rigidity

EXAMINATION TIP Recognizing Voluntary Rigidity

Distinguishing voluntary from involuntary abdominal rigidity is a must for accurate assessment. Review this comparison so that you can quickly tell the two apart.

VOLUNTARY RIGIDITY

- Usually symmetrical

- More rigid on inspiration (expiration causes muscle relaxation)

- Eased by relaxation techniques, such as positioning the patient comfortably and talking to him in a calm, soothing manner

- Painless when the patient sits up using his abdominal muscles alone

INVOLUNTARY RIGIDITY

- Usually asymmetrical

- Equally rigid on inspiration and expiration

- Unaffected by relaxation techniques

- Painful when the patient sits up using his abdominal muscles alone

- Insect toxins. Insect stings and bites, especially black widow spider bites, release toxins that can produce generalized, cramping abdominal pain, usually accompanied by rigidity. These toxins may also cause a low-grade fever, nausea, vomiting, tremors, and burning sensations in the hands and feet. Some patients develop increased salivation, hypertension, paresis, and hyperactive reflexes. Children commonly are restless, have an expiratory grunt, and keep their legs flexed.

- Mesenteric artery ischemia. A life-threatening disorder, mesenteric artery ischemia is characterized by 2 to 3 days of persistent, low-grade abdominal pain and diarrhea leading to sudden, severe abdominal pain and rigidity. Rigidity occurs in the central or periumbilical region and is accompanied by severe abdominal tenderness, fever, and signs of shock, such as tachycardia and hypotension. Other findings may include vomiting, anorexia, and diarrhea or constipation. Always suspect this disorder in patients older than age 50 who have a history of heart failure, arrhythmia, cardiovascular infarct, or hypotension.

- Peritonitis. Depending on the cause of peritonitis, abdominal rigidity may be localized or generalized. For example, if an inflamed appendix causes local peritonitis, rigidity may be localized in the right lower quadrant. If a perforated ulcer causes widespread peritonitis, rigidity may be generalized and, in severe cases, boardlike.

Peritonitis also causes sudden and severe abdominal pain that can be localized or generalized. In addition, it can produce abdominal tenderness and distention, rebound tenderness, guarding, hyperalgesia, hypoactive or absent bowel sounds, nausea, and vomiting. Usually, the patient also displays fever, chills, tachycardia, tachypnea, and hypotension.

Special Considerations

Continue to monitor the patient closely for signs of shock. Position him as comfortably as possible. The patient should lie in a supine position, with his head flat on the table, arms at his sides, and knees slightly flexed to relax the abdominal muscles. Because analgesics may mask symptoms, withhold them until a tentative diagnosis has been made. Because emergency surgery may be required, withhold food and fluids and administer an I.V. antibiotic. Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, which may include blood, urine, and stool studies; chest and abdominal X-rays; a computed tomography scan; magnetic resonance imaging; peritoneal lavage; and gastroscopy or colonoscopy. A pelvic or rectal examination may also be done.

Patient Counseling

Explain diagnostic tests or surgery the patient will need, and give him instruction on measures to reduce anxiety.

Pediatric Pointers

Voluntary rigidity may be difficult to distinguish from involuntary rigidity if associated pain makes the child restless, tense, or apprehensive. However, in any child with suspected involuntary rigidity, your priority is early detection of dehydration and shock, which can rapidly become life threatening.

Abdominal rigidity in the child can stem from gastric perforation, hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, duodenal obstruction, meconium ileus, intussusception, cystic fibrosis, celiac disease, and appendicitis.

Geriatric Pointers

Advanced age and impaired cognition decrease pain perception and intensity. Weakening of abdominal muscles may decrease muscle spasms and rigidity.

REFERENCES

Boeckxstaens, G. E., & de Jonge, W. J. (2009). Neuroimmune mechanisms in post-operative ileus. Gut, 58(9), 1300–1311.

Iyer, S., Saunders, W. B., & Stemkowski S. (2009). Economic burden of postoperative ileus associated with colectomy in the United States. Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy, 15(6), 485–494.

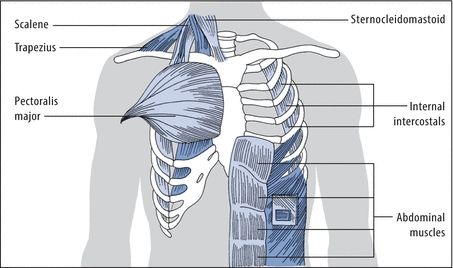

Accessory Muscle Use

When breathing requires extra effort, the accessory muscles — the sternocleidomastoid, scalene, pectoralis major, trapezius, internal intercostals, and abdominal muscles — stabilize the thorax during respiration. Some accessory muscle use normally takes place during such activities as singing, talking, coughing, defecating, and exercising. (See Accessory Muscles: Locations and Functions, page 28.) However, more pronounced use of these muscles may signal acute respiratory distress, diaphragmatic weakness, or fatigue. It may also result from chronic respiratory disease. Typically, the extent of accessory muscle use reflects the severity of the underlying cause.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient displays increased accessory muscle use, immediately look for signs of acute respiratory distress. These include a decreased level of consciousness, shortness of breath when speaking, tachypnea, intercostal and sternal retractions, cyanosis, adventitious breath sounds (such as wheezing or stridor), diaphoresis, nasal flaring, and extreme apprehension or agitation. Quickly auscultate for abnormal, diminished, or absent breath sounds. Check for airway obstruction, and, if detected, attempt to restore airway patency. Insert an airway, or intubate the patient. Then, begin suctioning and manual or mechanical ventilation. Assess oxygen saturation using pulse oximetry, if available. Administer oxygen; if the patient has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), use only a low flow rate for mild COPD exacerbations. You may need to use a high flow rate initially, but be attentive to the patient’s respiratory drive. Giving a patient with COPD too much oxygen may decrease his respiratory drive. An I.V. line may be required.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient’s condition allows, examine him more closely. Ask him about the onset, duration, and severity of associated signs and symptoms, such as dyspnea, chest pain, cough, or fever.

Explore his medical history, focusing on respiratory disorders, such as infection or COPD. Ask about cardiac disorders, such as heart failure, which may lead to pulmonary edema; also, inquire about neuromuscular disorders, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, which may affect respiratory muscle function. Note a history of allergies or asthma. Because collagen vascular diseases can cause diffuse infiltrative lung disease, ask about such conditions as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus erythematosus.

Accessory Muscles: Locations and Functions

Physical exertion and pulmonary disease usually increase the work of breathing, taxing the diaphragm and external intercostal muscles. When this happens, accessory muscles provide the extra effort needed to maintain respirations. The upper accessory muscles assist with inspiration, whereas the upper chest, sternum, internal intercostal, and abdominal muscles assist with expiration.

With inspiration, the scalene muscles elevate, fix, and expand the upper chest. The sternocleidomastoid muscles raise the sternum, expanding the chest’s anteroposterior and longitudinal dimensions. The pectoralis major elevates the chest, increasing its anteroposterior size, and the trapezius raises the thoracic cage.

With expiration, the internal intercostals depress the ribs, decreasing the chest size. The abdominal muscles pull the lower chest down, depress the lower ribs, and compress the abdominal contents, which exerts pressure on the chest.

Ask about recent trauma, especially to the spine or chest. Find out if the patient has recently undergone pulmonary function tests or received respiratory therapy. Ask about smoking and occupational exposure to chemical fumes or mineral dusts such as asbestos. Explore the family history for such disorders as cystic fibrosis and neurofibromatosis, which can cause diffuse infiltrative lung disease.

Perform a detailed chest examination, noting an abnormal respiratory rate, pattern, or depth. Assess the color, temperature, and turgor of the patient’s skin, and check for clubbing.

Medical Causes

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). In ARDS, a life-threatening disorder, accessory muscle use increases in response to hypoxia. It’s accompanied by intercostal, supracostal, and sternal retractions on inspiration and by grunting on expiration. Other characteristics include tachypnea, dyspnea, diaphoresis, diffuse crackles, and a cough with pink, frothy sputum. Worsening hypoxia produces anxiety, tachycardia, and mental sluggishness.

- Airway obstruction. Acute upper airway obstruction can be life threatening — fortunately, most obstructions are subacute or chronic. Typically, this disorder increases accessory muscle use. Its most telling sign, however, is inspiratory stridor. Associated signs and symptoms include dyspnea, tachypnea, gasping, wheezing, coughing, drooling, intercostal retractions, cyanosis, and tachycardia.

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Typically, this progressive motor neuron disorder affects the diaphragm more than the accessory muscles. As a result, increased accessory muscle use is characteristic. Other signs and symptoms include fasciculations, muscle atrophy and weakness, spasticity, bilateral Babinski’s reflex, and hyperactive deep tendon reflexes. Incoordination makes carrying out routine activities difficult for the patient. Associated signs and symptoms include impaired speech, difficulty chewing or swallowing and breathing, urinary frequency and urgency and, occasionally, choking and excessive drooling. (Note: Other neuromuscular disorders may produce similar signs and symptoms.) Although the patient’s mental status remains intact, his poor prognosis may cause periodic depression.

- Asthma. During acute asthma attacks, the patient usually displays increased accessory muscle use. Accompanying it are severe dyspnea, tachypnea, wheezing, a productive cough, nasal flaring, and cyanosis. Auscultation reveals faint or possibly absent breath sounds, musical crackles, and rhonchi. Other signs and symptoms include tachycardia, diaphoresis, and apprehension caused by air hunger. Chronic asthma may also cause barrel chest.

- Chronic bronchitis. With chronic bronchitis, a form of COPD, increased accessory muscle use may be chronic and is preceded by a productive cough and exertional dyspnea. Chronic bronchitis is accompanied by wheezing, basal crackles, tachypnea, jugular vein distention, prolonged expiration, barrel chest, and clubbing. Cyanosis and weight gain from edema account for the characteristic label of “blue bloater.” A low-grade fever may occur with secondary infection.

- Emphysema. Increased accessory muscle use occurs with progressive exertional dyspnea and a minimally productive cough in this form of COPD. Sometimes called a pink puffer, the patient will display pursed-lip breathing and tachypnea. Associated signs and symptoms include peripheral cyanosis, anorexia, weight loss, malaise, barrel chest, and clubbing. Auscultation reveals distant heart sounds; percussion detects hyperresonance.

- Pneumonia. Bacterial pneumonia usually produces increased accessory muscle use. Initially, this infection produces a sudden high fever with chills. Its associated signs and symptoms include chest pain, a productive cough, dyspnea, tachypnea, tachycardia, expiratory grunting, cyanosis, diaphoresis, and fine crackles.

- Pulmonary edema. With acute pulmonary edema, increased accessory muscle use is accompanied by dyspnea, tachypnea, orthopnea, crepitant crackles, wheezing, and a cough with pink, frothy sputum. Other findings include restlessness, tachycardia, ventricular gallop, and cool, clammy, cyanotic skin.

- Pulmonary embolism. Although signs and symptoms vary with the size, number, and location of the emboli, pulmonary embolism is a life-threatening disorder that may cause increased accessory muscle use. Typically, it produces dyspnea and tachypnea that may be accompanied by pleuritic or substernal chest pain. Other signs and symptoms include restlessness, anxiety, tachycardia, a productive cough, a low-grade fever and, with a large embolus, hemoptysis, cyanosis, syncope, jugular vein distention, scattered crackles, and focal wheezing.

- Spinal cord injury. Increased accessory muscle use may occur, depending on the location and severity of the injury. An injury below L1 typically doesn’t affect the diaphragm or accessory muscles, whereas an injury between C3 and C5 affects the upper respiratory muscles and diaphragm, causing increased accessory muscle use.

Associated signs and symptoms of spinal cord injury include unilateral or bilateral Babinski’s reflex, hyperactive deep tendon reflexes, spasticity, and variable or total loss of pain and temperature sensation, proprioception, and motor function. Horner’s syndrome (unilateral ptosis, pupillary constriction, facial anhidrosis) may occur with lower cervical cord injury.

- Thoracic injury. Increased accessory muscle use may occur, depending on the type and extent of injury. Associated signs and symptoms of this potentially life-threatening injury include an obvious chest wound or bruising, chest pain, dyspnea, cyanosis, and agitation. Signs of shock, such as tachycardia and hypotension, occur with significant blood loss.

Other Causes

- Diagnostic tests and treatments. Pulmonary function tests (PFTs), incentive spirometry, and intermittent positive-pressure breathing can increase accessory muscle use.

Special Considerations

If the patient is alert, elevate the head of the bed to make his breathing as easy as possible. Encourage him to get plenty of rest and to drink plenty of fluids to liquefy secretions. Administer oxygen. Prepare him for such tests as PFTs, chest X-rays, lung scans, arterial blood gas analysis, complete blood count, and sputum culture.

If appropriate, stress how smoking endangers the patient’s health, and refer him to an organized program to stop smoking. Also, teach him how to prevent infection. Explain the purpose of prescribed drugs, such as bronchodilators and mucolytics, and make sure he knows their dosage and schedule.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient relaxation techniques to reduce his apprehension, pursed-lip, diaphragmatic breathing to ease the work of breathing (for patients with chronic lung disorders) and coughing and deep breathing exercises to keep airways clear. Explain measures to prevent infection and how to take prescribed drugs, and provide resources for quitting smoking.

Pediatric Pointers

Because an infant or child tires sooner than an adult, respiratory distress can more rapidly precipitate respiratory failure. Upper airway obstruction — caused by edema, bronchospasm, or a foreign object — usually produces respiratory distress and increased accessory muscle use. Disorders associated with airway obstruction include acute epiglottiditis, croup, pertussis, cystic fibrosis, and asthma. Supraventricular, intercostal, or abdominal retractions indicate accessory muscle use.

Geriatric Pointers

Because of age-related loss of elasticity in the rib cage, accessory muscle use may be part of the older person’s normal breathing pattern.

REFERENCES

Groth, S. S., & Andrade, R. S. (2010). Diaphragm plication for eventration or paralysis: A review of the literature, Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 89(6), S2146–S2150.

Weiss, C., Witt, T., Grau, S., & Tonn, J. C. (2011). Hemidiaphragmatic paralysis with recurrent lung infections due to degenerative motor root compression of C3 and C4. Acta Neurochirurgica, 153(3), 597–599.

Agitation

(See Also Anxiety)

Agitation refers to a state of hyperarousal, increased tension, and irritability that can lead to confusion, hyperactivity, and overt hostility. Agitation can result from a toxic (poisons), metabolic, or infectious cause; brain injury; or a psychiatric disorder. It can also result from pain, fever, anxiety, drug use and withdrawal, hypersensitivity reactions, and various disorders. It can arise gradually or suddenly and last for minutes or months. Whether it’s mild or severe, agitation worsens with increased fever, pain, stress, or external stimuli.

Agitation alone merely signals a change in the patient’s condition. However, it’s a useful indicator of a developing disorder. Obtaining a good history is critical to determining the underlying cause of agitation.

History and Physical Examination

Determine the severity of the patient’s agitation by examining the number and quality of agitation-induced behaviors, such as emotional lability, confusion, memory loss, hyperactivity, and hostility. Obtain a history from the patient or a family member, including diet, known allergies, and use of herbal medicine.

Ask if the patient is being treated for any illnesses. Has he had any recent infections, trauma, stress, or changes in sleep patterns? Ask the patient about prescribed or over-the-counter drug use, including supplements and herbal medicines. Check for signs of drug abuse, such as needle tracks and dilated pupils. Ask about alcohol intake. Obtain the patient’s baseline vital signs and neurologic status for future comparison.

Medical Causes

- Alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Mild to severe agitation occurs in alcohol withdrawal syndrome, along with hyperactivity, tremors, and anxiety. With delirium, the potentially life-threatening stage of alcohol withdrawal, severe agitation accompanies hallucinations, insomnia, diaphoresis, and a depressed mood. The patient’s pulse rate and temperature rise as withdrawal progresses; status epilepticus, cardiac exhaustion, and shock can occur.

- Anxiety. Anxiety produces varying degrees of agitation. The patient may be unaware of his anxiety or may complain of it without knowing its cause. Other findings include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, cool and clammy skin, frontal headache, back pain, insomnia, depression, and tremors.

- Dementia. Mild to severe agitation can result from many common syndromes, such as Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s diseases. The patient may display a decrease in memory, attention span, problem-solving ability, and alertness. Hypoactivity, wandering behavior, hallucinations, aphasia, and insomnia may also occur.

- Drug withdrawal syndrome. Mild to severe agitation occurs in drug withdrawal syndrome. Related findings vary with the drug, but include anxiety, abdominal cramps, diaphoresis, and anorexia. With opioid or barbiturate withdrawal, a decreased level of consciousness (LOC), seizures, and elevated blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate can also occur.

- Hepatic encephalopathy. Agitation occurs only with fulminating encephalopathy. Other findings include drowsiness, stupor, fetor hepaticus, asterixis, and hyperreflexia.

- Hypersensitivity reaction. Moderate to severe agitation appears, possibly as the first sign of a reaction. Depending on the severity of the reaction, agitation may be accompanied by urticaria, pruritus, and facial and dependent edema.

With anaphylactic shock, a potentially life-threatening reaction, agitation occurs rapidly along with apprehension, urticaria or diffuse erythema, warm and moist skin, paresthesia, pruritus, edema, dyspnea, wheezing, stridor, hypotension, and tachycardia. Abdominal cramps, vomiting, and diarrhea can also occur.

- Hypoxemia. Beginning as restlessness, agitation rapidly worsens. The patient may be confused and have impaired judgment and motor coordination. He may also have headaches, tachycardia, tachypnea, dyspnea, and cyanosis.

- Increased intracranial pressure (ICP). Agitation usually precedes other early signs and symptoms, such as headache, nausea, and vomiting. Increased ICP produces respiratory changes, such as Cheyne-Stokes, cluster, ataxic, or apneustic breathing; sluggish, nonreactive, or unequal pupils; widening pulse pressure; tachycardia; a decreased LOC; seizures; and motor changes such as decerebrate or decorticate posture.

- Post-head trauma syndrome. Shortly after, or even years after injury, mild to severe agitation develops, characterized by disorientation, loss of concentration, angry outbursts, and emotional lability. Other findings include fatigue, wandering behavior, and poor judgment.

- Vitamin B6 deficiency. Agitation can range from mild to severe. Other effects include seizures, peripheral paresthesia, and dermatitis. Oculogyric crisis may also occur.

Other Causes

- Drugs. Mild to moderate agitation, which is commonly dose related, develops as an adverse reaction to central nervous system stimulants — especially appetite suppressants, such as amphetamines and amphetamine-like drugs, and sympathomimetics, such as ephedrine, caffeine, and theophylline.

- Radiographic contrast media. Reaction to the contrast medium injected during various diagnostic tests produces moderate to severe agitation along with other signs of hypersensitivity.

Special Considerations

Because agitation can be an early sign of many different disorders, continue to monitor the patient’s vital signs and neurologic status while the cause is being determined. Eliminate stressors, which can increase agitation. Provide adequate lighting, maintain a calm environment, and allow the patient ample time to sleep. Ensure a balanced diet, and provide vitamin supplements and hydration.

Remain calm, nonjudgmental, and nonargumentative. Use restraints sparingly because they tend to increase agitation. If appropriate, prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as a computed tomography scan, skull X-rays, magnetic resonance imaging, and blood studies.

Patient Counseling