OUTLINE

Dose Formats Used in Drug Therapy

Body Weight and Body Surface Area in Dose Expressions

Translating Dosage Regimens to Products and Directions for Use

I. INTRODUCTION

As stated in Chapter 8, an essential responsibility of the pharmacist is to ensure that each patient gets the correct amount of the intended drug. This function is the focus of this chapter on evaluating doses and dosage regimens. It builds on the subjects of systems and units of measurement, which were presented in Chapter 7, and on expressions of quantity and concentration, which were discussed in Chapter 8. This chapter examines the various accepted methods of expressing doses and dosage regimens and shows some sample dosing calculations. Special attention is given to patient populations and clinical statuses that require consideration of additional factors in establishing appropriate doses. In all instances of providing patients with drug products, whether they are manufactured dosage forms or preparations specially formulated by the pharmacist, the dose and dosage regimen must always be verified for accuracy and appropriateness before the product or preparation is delivered to the patient.

II. DOSE FORMATS USED IN DRUG THERAPY

A. Individual doses are expressed using one of the following formats:

1. Quantity of drug

For example, atenolol 25 mg, NPH insulin 10 units, potassium chloride 8 mEq

(See Chapter 8 for the various quantity expressions used for drugs in pharmacy and medicine.)

2. Quantity of drug per kilogram of patient body weight

For example, amoxicillin 20 mg/kg, heparin 50 units/kg, potassium phosphate 1.5 mmol/kg

3. Quantity of drug per square meter of patient body surface area (BSA)

For example, doxorubicin 70 mg/m2 and asparaginase 7,000 units/m2

B. For topical products and preparations, doses are expressed as concentrations. This makes conceptual sense as concentration gradient is the driving force for transfer of drug across the skin or membrane barrier. Examples include hydrocortisone 1% lotion or gentamicin 0.3% ophthalmic ointment. (See Chapter 8 for accepted methods of expressing concentrations and related sample calculations.)

C. Concentrations are also used to express doses for some intravenous solutions, such as dextrose 5% injection and sodium chloride 0.9% injection.

III. BODY WEIGHT AND BODY SURFACE AREA IN DOSE EXPRESSIONS

A. The formats for individual doses that are based on the patient’s body size (weight or BSA) are often used for pediatric doses, but they are also important when determining adult doses for drugs that have narrow therapeutic indices or that need precise individualized dosing. BSA is routinely used for dosing chemotherapy agents, but it is also used in other selected situations. Pharmacists need patient-specific information on body weight or BSA in the following circumstances.

1. Most often, drug orders are written in terms of a quantity of drug (e.g., mg, unit, mEq). Before preparing the prescription or medication order, the pharmacist verifies the correctness of the dose. If the drug information reference gives the dose as a quantity per kilogram body weight or based on BSA, the pharmacist needs this patient information to check the prescribed dose for appropriateness.

2. In same cases, a prescriber will write a drug order in terms of a quantity of drug per kilogram of body weight (or square meter BSA) or will prescribe a drug, such as an antibiotic for a pediatric patient, and will ask the pharmacist to dose the patient on the basis of that patient’s weight. In cases like this, the pharmacist needs the patient’s weight to provide the proper dose.

3. Some types of therapy, such as chemotherapy and total parenteral nutrition, use protocols based on patient weight or BSA. In these situations, the pharmacist needs these patient dimensions to calculate the needed quantities of drugs, electrolytes, or nutrients.

B. Body weight

1. There are two types of body weight used in calculating doses: actual body weight (ABW) and ideal body weight (IBW). In most cases, the patient’s ABW is used.

a. If the patient is an inpatient, this information can usually be found in the patient’s medical chart. If the information is not in the chart, ask the nurse who is taking care of that patient; this is often necessary when evaluating orders for newly admitted patients.

b. If this is an ambulatory or outpatient, the pharmacist or pharmacy technician can obtain this information from the prescriber’s office or the patient or patient caregiver. Realize that body weight can be a sensitive issue for some patients, so it is essential to be tactful and to communicate with the patient about the purpose for this information and the importance of accurate information in establishing a correct dose.

c. For pediatric outpatients, an initial check of dosage range can be made if the child’s age is known. An estimate of the patient’s body weight can be obtained from one of the percentile charts of body weight versus age. Percentile weight-height measurements based on ages for infants and children are given in Appendix C and on the CD that accompanies this book. The charts in Appendix C are also available on the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Internet site at http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/. Though charts like this are handy for initial checking of dosage ranges, the dose should always be verified based on the child’s ABW.

2. For some types of therapy, dosing is based on estimated IBW, also referred to as lean body weight (LBW). IBW is a calculated weight based on gender, height (or length for infants and children), and, for pediatric patients, age of the patient. As the LBW name implies, this is what the person would weigh if he or she had little or no fat or adipose tissue. This weight is especially useful for dosing drugs that do not distribute into adipose tissue; drugs such as these have a smaller volume of distribution than the entire body mass (especially for obese patients who have significant adipose tissue) so that basing the dose on ABW would result in a drug blood concentration that is higher than desired. Both ABW and IBW are used for TPN therapy calculations because, though adequate nourishment is needed, it would not be desirable to maintain an overweight state using parenteral nutrition.

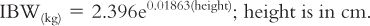

3. The following equations are used to calculate estimated IBW in kilograms. For children, several methods are shown based on age or height. The last equation given for children ages 1 to 17 years is based on CDC data for the fiftieth percentile weight for children of a given age and gender. As mentioned earlier, the CDC weight/height charts are shown in Appendix C; these can be used to determine an IBW for a child of a given age by choosing the weight at the fiftieth percentile (1).

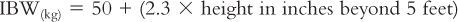

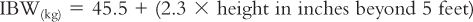

Female Adults:

Children:

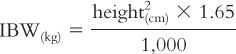

Children less than 5 feet tall (2):

Children 5 feet and taller (2)

Boys:

Girls:

Ages 1 to 17 years (1)

C. Body surface area (BSA)

1. Drug dosage may also be based on estimated BSA of the patient. This parameter is sometimes used for pediatric dosing and, as previously stated, many cancer drug protocols base dosage on BSA. When a dose is given in terms of drug quantity per square meter of BSA, the pharmacist must use the patient’s weight and height (or length for an infant) plus either an equation or a BSA nomogram to determine a value for the patient’s BSA. Though some clinicians think that BSA is a better parameter than body weight for individualizing doses for patients, this is a subject that is still debated.

2. There are numerous BSA equations and each will give a slightly (or moderately) different answer. It should be understood that BSA is not a measurement (like a height or a weight) taken of the individual patient. It is an estimate based on an equation that was developed experimentally using a selected representative patient population. The weights, heights, and BSA of these patients were measured and correlated using an equation that mathematically modeled the experimental results. The first work on BSA was published in 1916 by DuBois and DuBois (3), but numerous other studies have subsequently been conducted. For more information on BSA equations, see a book on pharmaceutical calculations or one of the Internet Web sites devoted to this issue.

3. BSA nomograms for adults and children are shown in Appendix B and are based on the equations of DuBois and DuBois (3). They are used as follows:

a. Find the patient’s weight in pounds or kilograms on the right-hand side of the nomogram.

b. Find the patient’s height in inches or centimeters on the left-hand side of the nomogram.

c. Draw a straight line connecting these two points and read the BSA in square meters at the point where the line intersects with the middle BSA line.

4. BSA can also be calculated using one of the equations developed for that purpose. Because the various equations give slightly different BSA values, some hospitals and clinics have standardized which equation will be used in their facility; this makes it easier to check and verify doses based on BSA. The equations given below were originally published by Mosteller (4,5); they have gained favor in clinical practice because BSA calculations can be done quite easily using one of these equations and a hand-held calculator (6).

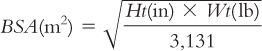

a. Using weight in pounds and height in inches:

b. Using weight in kilograms and height in centimeters:

IV. DOSAGE REGIMENS

A.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree