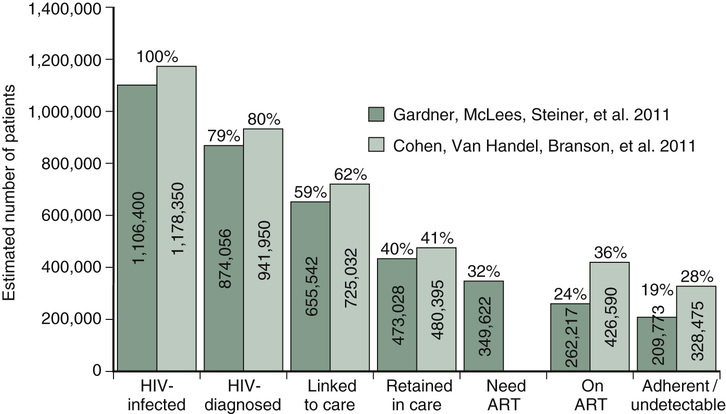

Christopher J. Graber Obtaining a detailed social history is critical in determining the right time for ART initiation and devising the appropriate regimen. It is particularly relevant to know the patient’s risk factor(s) for HIV acquisition and whether the patient still engages in those risk factors, as the patient is highly infectious in his currently untreated state. Substance abuse may represent a significant barrier to ART compliance and should be investigated, with treatment referral as appropriate. An assessment of the patient’s current living situation and social support will also help you assess the patient’s ability to be compliant with ART. There are several potential benefits to starting ART at this time. Some of the best data to support earlier ART initiation in the context of presentation with an opportunistic infection (OI) come from a randomized clinical trial in which HIV-infected patients who were not taking antiretroviral therapy at the time of OI presentation were randomized to start antiretroviral therapy either within 2 weeks of starting OI treatment or to defer antiretroviral therapy until OI treatment was complete. Patients in the early ART arm started a median of 12 days into their OI treatment, compared to 45 days in the deferred arm. Patients in the early ART arm had a lower rate of and longer time to death or progression of disease, with no increase in adverse events or loss of virologic response. There are a few caveats to this trial: most (63% of) patients in the trial had Pneumocystis pneumonia as their presenting OI; a much smaller proportion had cryptococcal meningitis or mycobacterial disease, two conditions for which the decision-making for when to start therapy may be more complex, owing to potential severity of the immune reconstitution syndrome that may develop and the potential for drug–drug interactions, among other factors. Overall, however, it appears that starting ART sooner rather than later can have a long-lasting effect on immune restoration and may help modulate more subtle effects that HIV infection has on other comorbidities. Another potential benefit of starting ART now is that it can serve as an impetus to engage in regular HIV care upon discharge. In the United States, despite near-universal availability of ART, several gaps exist in the continuum of care between time of HIV infection, diagnosis, engagement in care, retention in care, receipt of ART, and adherence to ART in what is commonly referred to as the “HIV care cascade” (see Fig. 59.1). It has been estimated that only about one quarter of all HIV-infected patients in the United States are adherent to ART and have undetectable viral load. However, if patients can be effectively adherent to ART and maintain an undetectable HIV viral load long term, they can expect to have a relatively normal lifespan, particularly if ART is started at higher initial CD4 counts. Starting ART now also has the benefit of reducing transmission of HIV from the patient to other people. Although this phenomenon is best described in a trial of mostly heterosexual HIV-discordant couples, in which treatment of the HIV-infected partner reduced HIV transmission by 96%, there is evidence to support that ART reduces HIV transmission in other settings as well. There are potential barriers to successful adherence to ART that should be addressed as best as possible at the time of ART initiation, including mental health disease, substance abuse, unstable housing, and food insecurity. Patients may not fully understand their treatment regimen. Perhaps most importantly, patients are not likely to be adherent to ART if they are not motivated to do so, so exploring this motivation is critical prior to ART initiation. Regardless of the timing of ART initiation, prophylaxis against OI (based on CD4 count) should be started promptly (see Table 59.1). TABLE 59.1 Prophylaxis for Opportunistic Infection According to CD4 Count The optimal CD4 cell count at which to start ART has been controversial throughout the history of the HIV epidemic. In the early days of the epidemic, ART was not as effective, more toxic, and far more inconvenient to take than the options available today, so the risks and adverse effects of ART had to be balanced with its benefits. Now, as ART is highly effective, less toxic, and more convenient, it is easier to show the benefits of starting ART at higher CD4 cell counts than before. Randomized controlled trial data now support the benefits of starting ART at a CD4 count of 500 cells/mm3. Guidelines from the United States Department of Health and Human Services (as of the April 2015 update) recommend offering ART to all HIV-infected individuals to reduce the risk of disease progression and transmission, regardless of CD4 count.

A 34-Year-Old Male With Generalized Weakness

What aspects of the patient’s social history would influence the decision to initiate ART?

What are the benefits and risks of starting ART now in this patient?

Opportunistic Infection

When to Start Prophylaxis

Prophylaxis Options

Pneumocystis pneumonia

CD4 <200 cells/mm3 or 14%, or patient presenting with oropharyngeal candidiasis

TMP-SMX, dapsone (check G6PD), atovaquone, aerosolized pentamidine

Toxoplasma encephalitis

CD4 <100 cells/mm3 with IgG+

TMP-SMX, atovaquone, dapsone plus pyrimethamine plus leucovorin

Disseminated mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) infection

CD4 <50 cells/mm3 (after ruling out active MAC disease)

Azithromycin 1200 mg weekly

Histoplasma

CD4 <150 cells/mm3 with high risk of occupational exposure or area of hyperendemicity

Itraconazole 200 mg daily

Penicillium marneffei

CD4 <100 cells/mm3 with prolonged stay in rural northern Thailand, Vietnam, or southern China

Itraconazole 200 mg daily or fluconazole 400 mg daily

Is there a CD4 cell count threshold that should determine when ART should be started?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree