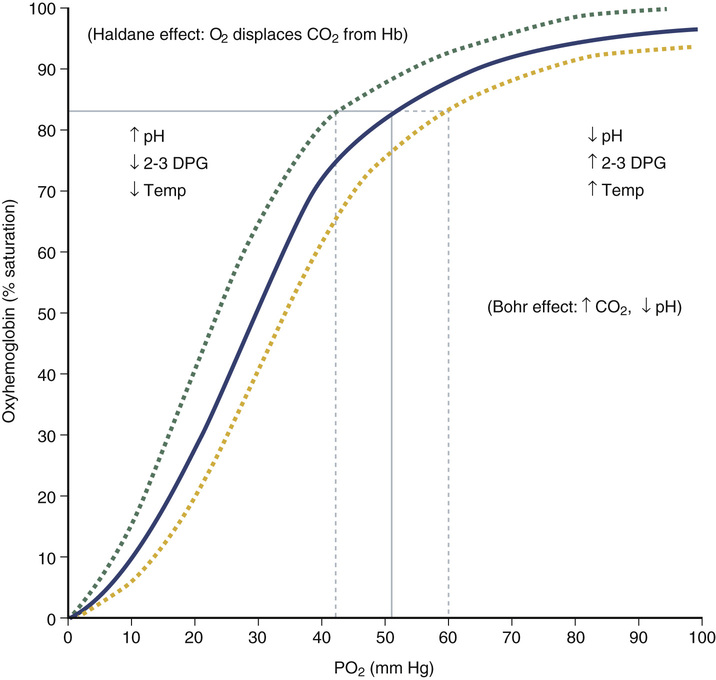

Walter Chou, Aarti Chawla Mittal, Raj Dasgupta, Stanley Silverman Although the differential diagnosis for cough and shortness of breath is broad, a few key points in the history narrow it down for us. We become more suspicious of pneumonia given that the patient has fevers and a productive cough. If the patient had heart failure and another source of infection (i.e., a urinary tract infection), this could lead to a decompensation of his heart failure causing his fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Other things to consider are an acute exacerbation of an underlying pulmonary disease such as asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The first thing that comes to mind is a chest radiograph (CXR). Labs include a basic metabolic panel and a complete blood count (CBC) with differential. For the fever workup, you would also obtain blood cultures, sputum culture, and a urinalysis with microscopy. All of these vital signs, except for the blood pressure, are very concerning. The most immediately worrisome ones are the high respiration rate (tachypnea) and low oxygen saturation (hypoxia). The first thing that needs to be done is to place the patient on supplemental oxygen. You also want to order an arterial blood gas (ABG) to evaluate the acid-base status and confirm the hypoxemia. Figure 57.1 is the oxygen-hemoglobin dissociation curve. It shows how blood (specifically hemoglobin) binds and releases oxygen molecules. Each hemoglobin molecule can reversibly bind four oxygen molecules. The curve is in a sigmoid shape because binding the first molecule to hemoglobin is difficult. After the first one is bound, the structure of hemoglobin changes, and binding each successive oxygen molecule becomes easier. The binding is based on the partial pressure of oxygen. In the alveoli, the partial pressure is very high, so oxygen is bound easily. In the tissues, the partial pressure varies depending on the clinical situation. If the curve is shifted to the right, it means that the oxygen is not tightly bound and is unloaded more readily. This occurs during periods of increased tissue oxygen consumption (e.g., in elevated temperatures and with acidosis). Similarly, if the curve is shifted to the left, there is a reluctance to release oxygen from hemoglobin (e.g., with alkalosis). Looking at the pH first lets you know that this is an acidosis. Now let’s see if its metabolic, respiratory, or both. Respirations are driven by the level of carbon dioxide in the blood, which is normally around 40 mm Hg. The patient has a level just slightly below that. Remember that carbon dioxide is an “acid,” so lower levels are due to a respiratory alkalosis. Next, look at the bicarbonate, which is a base, or alkali. The patient has a bicarbonate level of 18 mEq/L, whereas a normal level is 24 mEq/L. Overall, the patient has a metabolic acidosis, but his body is trying to compensate with a respiratory alkalosis. Lastly, look at the PO2 in the blood. Normal PO2 on room air is in the range of 95 mm Hg. On room air, the patient’s PO2 is extremely low, thus indicating that he is severely hypoxemic. It’s a good thing you have already placed him on supplemental oxygen.

A 56-Year-Old Male With Cough and Shortness of Breath

What is likely to be the cause of his cough and shortness of breath?

What studies should you order?

What do you want to do now?

How do you interpret this arterial blood gas?

How do you interpret the patient’s CXR?

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

57 A 56-Year-Old Male With Cough and Shortness of Breath

Case 57