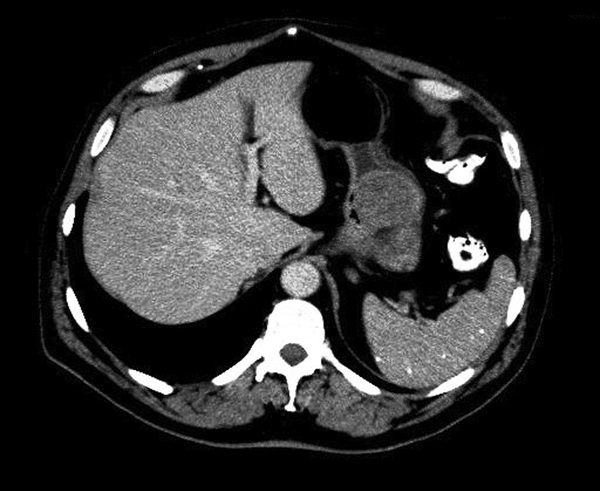

Monisha Bhanote, Daniel Martinez In the absence of a malabsorptive pathology or extreme malnutrition, iron deficiency anemia is generally caused by chronic blood loss of some time. It is typical for the source of bleeding to be from a gastrointestinal source. Referring this patient for a colonoscopy because of his symptoms of bright red blood per rectum in the setting of iron deficiency anemia was the correct decision at the time. However, the presence of one source of bleeding does not itself rule out the possibility of other sources of bleeding. Generally speaking, patients with an iron deficiency anemia should receive both a colonoscopy and an upper endoscopy to rule out other sources of bleeding such as a gastric or duodenal ulcer. This is especially the case when the patient is still iron dependent after his polyps are removed and his hemorrhoids are treated with a high-fiber diet. When the source of bleeding has been removed, a patient’s iron stores should replenish in a few months of oral iron supplementation. Failure to do so should have prompted the PMD to evaluate further sources of occult bleeding. The differential diagnosis for new-onset abdominal pain is very wide, and a good way to think about common causes is by considering the potential organs involved. In the left upper quadrant, the pancreas can be involved by pancreatitis and the stomach can be involved by a peptic ulcer or a mass. In the right upper quadrant, the hepatobiliary system can be involved by cholecystitis, cholangitis, or biliary colic. In the left lower and right lower quadrants, the small intestines and colon can be involved with diverticulitis, appendicitis, bowel obstruction, inflammatory bowel disease, and colonic masses. The possibility of bony metastasis or metastasis to other organs should be considered in a patient with a previously diagnosed malignancy. Another rare consideration is aortic dissection or ruptured aneurysm in the right clinical setting. If any of these are reasonable suspicions based on his clinical presentation, it is appropriate to order a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen/pelvis with intravenous (IV) contrast. (The addition of oral [PO] contrast can also help evaluate the bowel better for a small bowel obstruction.) Submucosal masses can be benign or malignant, and the differential diagnosis of a submucosal mass can be divided into mesenchymal versus nonmesenchymal lesions (see Table 56.1).

A 70-Year-Old Male With Iron Deficiency Anemia

Does the patient still need iron supplementation?

What are some considerations of abdominal pain in this patient?

What is the differential diagnosis of a gastric submucosal mass?

56 A 70-Year-Old Male With Iron Deficiency Anemia

Case 56