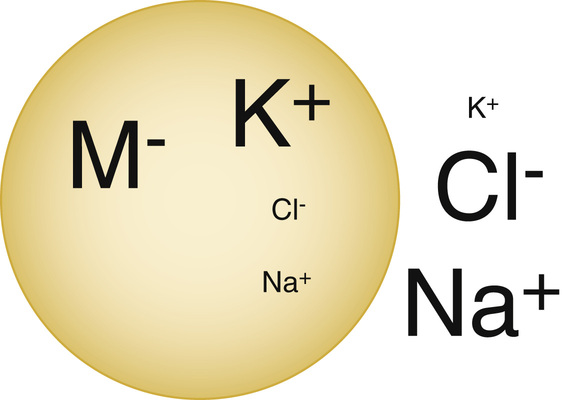

Daniel Martinez The patient’s history is very concerning for diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). Her history of DM1 with decreased oral intake and a lack of insulin places her at high risk for DKA. Other causes of DKA include infection/sepsis, intoxication (alcohol/drugs), myocardial infarction, stroke, and pancreatitis. There are three basic requirements to diagnose someone with DKA. There needs to be a plasma glucose >250 mg/dL, an anion gap acidosis with pH <7.3, and ketosis. The basic evaluation of DKA thus involves measuring a glucose finger-stick, a basic metabolic panel, arterial blood gas, and urinalysis. The pathophysiology of DKA involves far more than hyperglycemia and anion gap ketoacidosis. Another major pathology is the osmotic diuresis that occurs when blood glucose levels are consistently that high. As glucose is filtered into the renal tubules, it pulls in water and other important electrolytes with it. This causes severe polyuria/polydipsia, dehydration, hypokalemia, and hypomagnesemia. The treatment of DKA therefore commonly involves aggressive replacement of fluids and electrolytes. It is important to remember that potassium is mainly an intracellular electrolyte, and therefore a serum potassium level is not always an accurate representation of total body potassium (see Fig. 52.1). A thorough understanding of the causes of hypokalemia and a detailed history that screens for these causes is the best way to estimate a patient’s total body potassium. That is the only way to manage a patient’s potassium levels effectively. Causes of hypokalemia can be classified into four major categories. The first category is a decreased intake of potassium; second is potassium loss via the gastrointestinal tract; third is potassium loss via the renal system; and fourth is a transcellular shift of potassium into cells (see Table 52.1). TABLE 52.1 Evaluation of Hypokalemia It is rare for a healthy individual to develop hypokalemia simply by not eating enough as there is a sufficient amount of potassium in the normal Western diet. However, this is a very common reason for hospitalized patients to develop hypokalemia. Many patients have severe nausea/vomiting and cannot tolerate a regular diet. Other patients are instructed not to eat or drink for a procedure or as a therapeutic modality for an underlying illness (ileus, pancreatitis, etc.). It is also common for postoperative patients not to be able to eat for many days following a surgery. This is why potassium is added to maintenance IV fluids when patients are not able to eat in the hospital. Depending on their condition, patients may need between 40 and 80 mEq of potassium chloride (KCl) a day (which is why you will commonly see patients get about 2 to 3 liters of maintenance fluids per day, with 20 to 40 mEq of KCl added per liter). Diarrhea is a common cause for relatively minor levels of hypokalemia. It is not a cause of hypokalemia that requires a significant workup to rule in as it is evident from the patient’s history. It is more important to understand that when patients are having diarrhea, it is helpful to keep a close eye on their serum potassium and appropriately replace it. Furthermore, the presence of diarrhea does not itself rule out other causes of hypokalemia, and they should be investigated when clinically indicated. The definitive workup of potassium losses from the kidneys is complicated and will be discussed later in this chapter. However, the initial step to evaluate whether the kidneys are involved as an etiology for hypokalemia is very simple: A spot urine potassium concentration can be used. If urine potassium is >15 mEq/L, the kidneys are likely playing a role in the patient’s hypokalemia. In a state of hypokalemia, normal functioning kidneys are very good at minimizing renal potassium losses, and this dramatically lowers the urine potassium concentration. Therefore, if the potassium is found at a normal to high concentration in the urine, there is likely something going wrong with the kidneys themselves, and further workup is indicated. Different physiologic states and medications can cause a transcellular shift of potassium into cells without actually altering the total body potassium. Most commonly, this includes an alkalemic state and beta-2-agonist or insulin administration. Alternatively, an acidemic state or a lack of insulin can cause a transcellular shift of potassium out of the cells. A “normal” serum potassium concretion in this instance can mislead physicians to presume a patient’s total body potassium is relatively normal when in fact a patient can be severely total body potassium depleted.

A 45-Year-Old Female With Nausea, Vomiting, and Abdominal Pain

What is concerning about this presentation?

How should you begin workup of this patient?

What other abnormalities are found in DKA?

Why isn’t the patient’s potassium very low?

What are the causes of hypokalemia?

Etiology of Hypokalemia

Transtubular Potassium Gradient

History

Decreased intake

Low

Nausea/vomiting/restriction of oral food and fluids (NPO)

Gastrointestinal losses

Low

Diarrhea

Renal losses

High

Variable

Transcellular shifting

Variable

Alkalemia/insulin excess/beta-2 agonists

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

52 A 45-Year-Old Female With Nausea, Vomiting, and Abdominal Pain

Case 52

Figure 52.1 A graphic depiction of the relative concentrations of ions inside and outside the typical human cell. Note that potassium is mainly an intracellular ion, so it is difficult to gauge how much potassium is in the body simply by measuring how much is in the extracellular fluid. (From http://aups.org.au/Proceedings/42/19-28/Figure_1.jpg.)