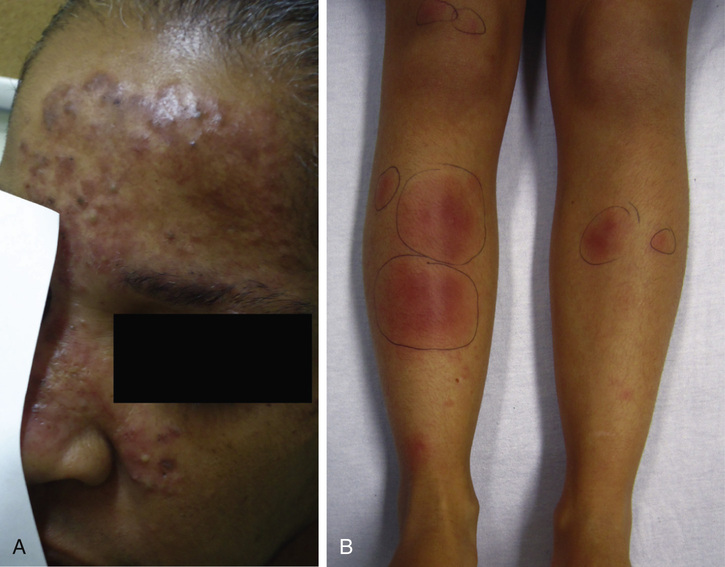

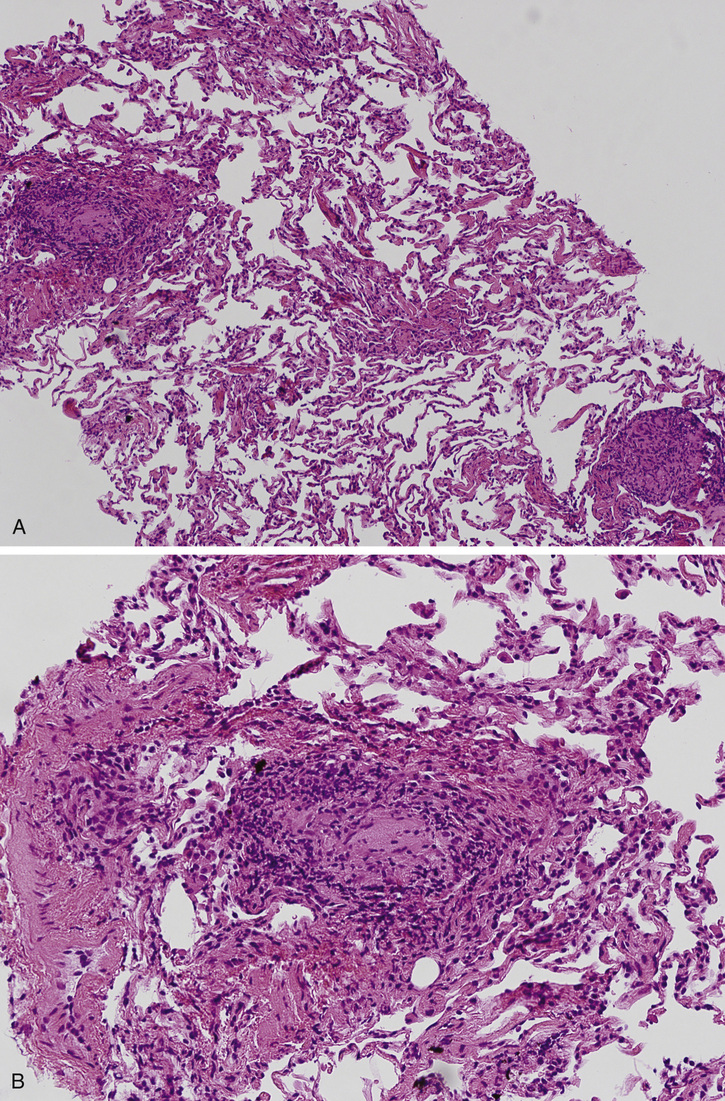

Nicholas Landsman, Kelly Walsma, Raj Dasgupta, Richard Snyder Chronic cough is an extremely common complaint seen in the outpatient setting. Knowing the most common causes of a chronic cough can eliminate unnecessary tests that increase health care costs. The four most common causes of cough include gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), asthma, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and upper airway cough syndrome. A detailed and focused history can lead to a diagnosis quickly (see Table 46.1). TABLE 46.1 Etiologies of Chronic Cough Previously postnasal drip syndrome; history of nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, recurrent throat clearing Associated with sinusitis, allergies, vasomotor rhinitis Shortness of breath, decreased exercise tolerance, wheezing, dyspnea Cough-variant asthma with cough as dominant feature; may occur in absence of wheeze Heartburn, acid/sour taste in mouth, acid-reflux symptoms are worse at night A variant of GERD: laryngopharyngeal reflux, with hoarseness, dysphagia Current or former smoker, yet increasingly among nonsmokers Generally large central airway bronchogenic carcinoma; new or change in chronic “smoker’s cough” persistent after smoking cessation; hemoptysis in absence of infection Metastatic disease or bulky lymphadenopathy from lymphoma are rare etiologies A diagnostic algorithm for chronic cough has been proposed by the American College of Chest Physicians, and practice guidelines have been developed and published. The facial rash and presence of erythema nodosum is most likely a sign of systemic disease. Although infectious etiologies such as tuberculosis (TB) are still within the differential, the patient’s lack of productive cough and known risk factors (institutionalization, immunosuppression, exposure history) argue against this diagnosis. The rash is not typical of rheumatologic disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), which is generally a malar or discoid facial rash. Although the patient is young with a limited smoking history, a primary lung malignancy or metastatic disease cannot be excluded. The cutaneous and pulmonary manifestations are consistent with sarcoidosis, and this should be at the forefront of the differential diagnosis. Nevertheless, sarcoidosis is a diagnosis of exclusion, and other granulomatous diseases and malignancies such as lymphoma, lung cancer, metastatic disease, infection, carcinoid tumors, vasculitides, and collagen vascular diseases must be ruled out. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is confirmed by three essential clinical characteristics, including evidence on CXR, clinical features as noted above with suspicion for sarcoidosis, and nonnecrotizing granulomata on biopsy of an affected organ in the absence of an alternative etiology. Table 46.2 provides an overview of the clinical manifestations of sarcoidosis. Peripheral blood samples have been shown to have elevated tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha levels in sarcoidosis patients, yet assays have not yet been standardized or tested for routine clinical efficacy to date. There is currently no widely accepted or consensus guideline available for workup of suspected sarcoidosis. If sarcoidosis is suspected based on presentation and imaging, then a biopsy of the suspected organ involved should be pursued. A minor salivary gland biopsy, transbronchial needle aspiration, endobronchial ultrasound lymph node biopsy, or transbronchial lung biopsy is warranted in the absence of a peripheral lymph node or skin biopsy site. The granulomas of TB tend to contain necrosis, but nonnecrotizing granulomas may also be present. A definitive diagnosis of TB requires identification of the organism by microbiologic cultures. It is important to consider TB as part of the differential diagnosis because immunosuppressive therapy (the treatment for sarcoidosis, to be discussed later) can be detrimental if initiated in a patient who actually has TB. The clinical suspicion for TB is low, but ruling this out definitively is valuable nonetheless. Chronic beryllium disease is another granulomatous disease, primarily of the lung, most associated with occupational exposure. A type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction due to beryllium exposure also characterizes chronic beryllium disease. The noncaseating, epithelioid granulomata found in the lung are indistinguishable histopathologically from sarcoidosis. A detailed history is essential to its diagnosis, and if uncertainty or ambiguous history is noted, then a peripheral blood beryllium lymphocyte proliferation test (BeLPT) is necessary to distinguish chronic beryllium disease from pulmonary sarcoidosis. Common variable immunodeficiency, characterized by hypogammaglobulinemia with absent or decreased levels of specific antibody production leading to recurrent infections, also mimics sarcoidosis. Granulomatous and lymphocytic interstitial lung disease has been reported in up to 20% of patients with common variable immunodeficiency, and like sarcoidosis can involve multiple organs. Key differences include recurrent infections, autoimmunity, and extrapulmonary manifestations favoring liver and spleen in common variable immunodeficiency compared to sarcoidosis. High-resolution computed tomography (CT) scans of the lungs favor predominately lower lobe disease with significant nodularity in common variable immunodeficiency.

A 40-Year-Old Female With Facial Rash and Persistent Cough

What are the most common etiologies of a chronic cough?

Diagnosis

Presentation

Upper airway cough syndrome (UACS)

Asthma

Nonasthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis (NAEB)

Chronic cough associated with atopic findings; may be indistinguishable from cough-variant asthma initially

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Generally due to chronic bronchitis, productive cough for most days for at least 3-month period over 2 consecutive years, without alternative etiology

Postinfectious

Recent viral/bacterial upper respiratory tract infection or pneumonia; cough generally only lasts 8 weeks yet may persist longer

Opportunistic infections (i.e., mycobacterial infections, Pneumocystis jiroveci)

Immunocompromised patient due to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), immune deficiency syndromes; organ transplant or autoimmune disease patients on chronic immunosuppressive therapy

Medication induced

Most notable is angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor use, usually within 1 week yet may be delayed up to 6 months

Lung cancer/metastatic disease

How does the patient’s skin exam affect the differential diagnosis?

What is the most likely diagnosis? How can this be confirmed?

Why is it important to check the AFB smear and culture in this case?

What illnesses can mimic the clinical presentation of sarcoidosis?

What is the CXR scoring system for sarcoidosis?

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

46 A 40-Year-Old Female With Facial Rash and Persistent Cough

Case 46