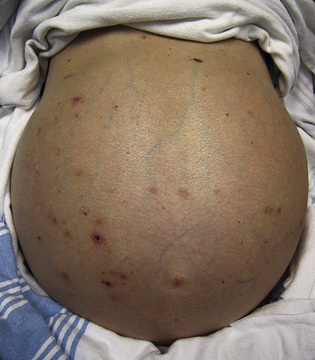

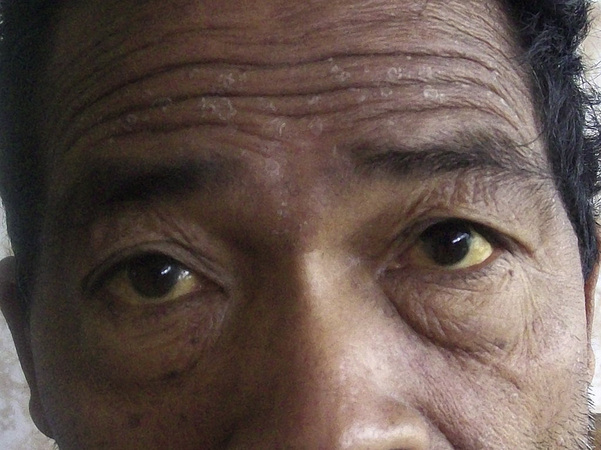

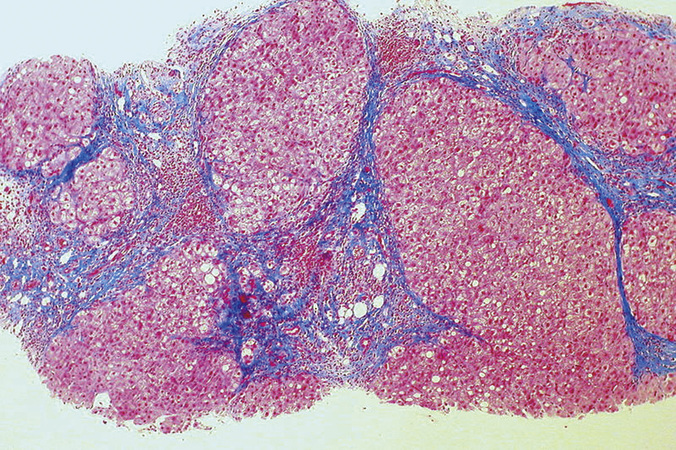

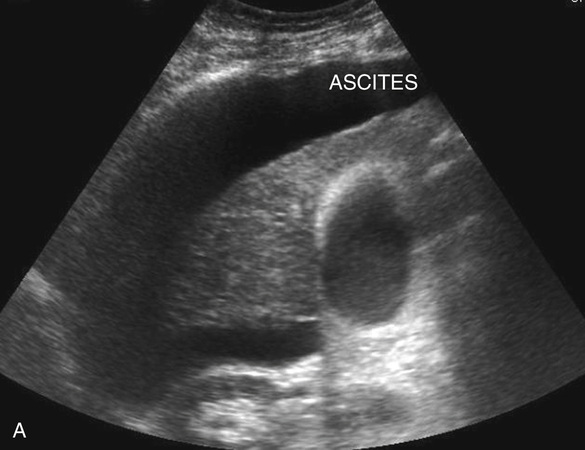

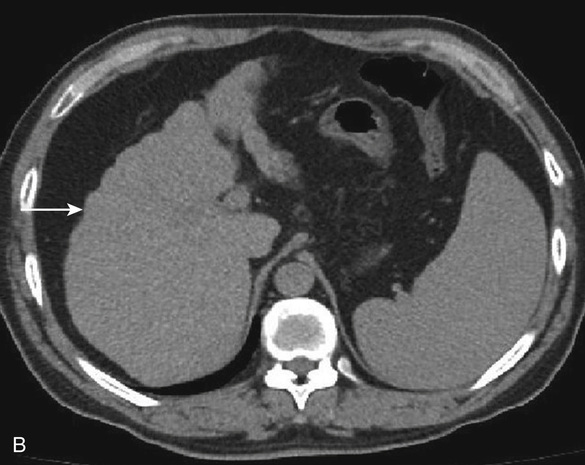

Monisha Bhanote, Wen Chen, Daniel Martinez There are many classic physical exam findings associated with cirrhosis, and this vignette is designed to illustrate most of them. These are important to put to memory because recognizing them helps to make a bedside diagnosis, and they are also common questions that an attending may ask. Patients with cirrhosis can also have many acute and life-threatening complications. Knowing early on that a patient likely has cirrhosis can help you place these pathologies on your initial differential diagnosis and affect your initial workup and management (see Table 43.1). TABLE 43.1 Physical and Laboratory Exam Findings in Chronic Liver Disease Being able to assess and differentiate between acute, chronic, and acute on chronic pathologies is a necessary skill to be a good clinician. This is especially the case in a patient with many chronic comorbid conditions that can flare up. The patient likely has a chronic diagnosis of cirrhosis, but this alone does not explain his acute presentation (3 days of abdominal pain, fevers, and nausea). It is important not to let a chronic diagnosis detract you or mislead you from the acute presentation. Patients with cirrhosis can get acute appendicitis, cholecystitis, and cholangitis like anyone else, so these should be on the differential. With his drinking history, he can also have acute pancreatitis like anyone else. However, keeping cirrhosis in mind, the differential expands to other acute pathologies such as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, portal venous thrombosis, or even gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. In the emergency room setting, the workup should include labs and imaging directed at evaluating these life-threatening pathologies. An abdominal ultrasound with Doppler would be very helpful as it could evaluate for cholecystitis, appendicitis, cholangitis, cirrhosis, portal vein thrombosis, and the presence of ascites. A complete blood count (CBC), blood cultures, hepatic function panel, basic metabolic panel (BMP), lipase, and prothrombin time would also be helpful for the differential diagnosis. Cirrhosis is the last stage of progressive liver fibrosis due to chronic liver damage and is characterized by a coarsening of the liver architecture and the formation of regenerative nodules. The gold standard for the diagnosis of cirrhosis is a liver biopsy, but a presumptive diagnosis of cirrhosis can be made if the patient has a constellation of physical exam findings, laboratory abnormalities, or imaging studies suggestive of cirrhosis. Obvious physical exam findings in cirrhosis include scleral icterus, jaundice, spider angiomata, caput medusa, ascites, palmar erythema, and splenomegaly. More subtle findings include parotid gland enlargement, fetor hepaticus, gynecomastia, and two classes of nail pallor (Muehrcke’s nails and Terry’s nails). Common laboratory abnormalities in cirrhosis include anemia, thrombocytopenia, elevated prothrombin time, low fibrinogen, hypoalbuminemia, mildly elevated transaminases, and increased direct and indirect bilirubin (see Table 43.1, Fig. 43.3, and Fig. 43.4). Common imaging tests used to diagnose cirrhosis include a right upper quadrant ultrasound, which can show a nodularity of the surface of the liver and evidence of portal hypertension such as ascites and splenomegaly. A computed tomography (CT) scan of liver may also show similar findings (see Fig. 43.5). The most common causes of cirrhosis in the United States are chronic viral hepatitis (hepatitis B and hepatitis C), alcoholic liver disease, fatty liver disease, and hemochromatosis (see Fig. 43.6 and Table 43.2).

A 55-Year-Old Male With Fever and Abdominal Pain

What is concerning about his physical exam?

Physical Findings

Laboratory Findings

Ascites

Elevated partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, international normalized ratio

Spider angiomas

Macrocytic anemia

Asterixis

Thrombocytopenia

Splenomegaly

Acanthocytosis on peripheral smear

Palmar erythema

Elevated blood urea nitrogen and creatinine

Dupuytren’s contracture

Hyperbilirubinemia

Testicular atrophy

Hypoalbuminemia

Gynecomastia

Aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase variable

Knowing that he has a decent chance at having cirrhosis based on exam, how would you approach this patient?

What is cirrhosis and how is it diagnosed?

What are the most common causes of cirrhosis?

43 A 55-Year-Old Male With Fever and Abdominal Pain

Case 43

Figure 43.5 A, Ultrasound image showing a coarsened cirrhotic liver surround by ascites. B, Computed tomography (CT) image showing a nodular cirrhotic liver and splenomegaly. (A from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ascites_ultrasound_2.JPG; B from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Liver_cirrhosis.JPG.)