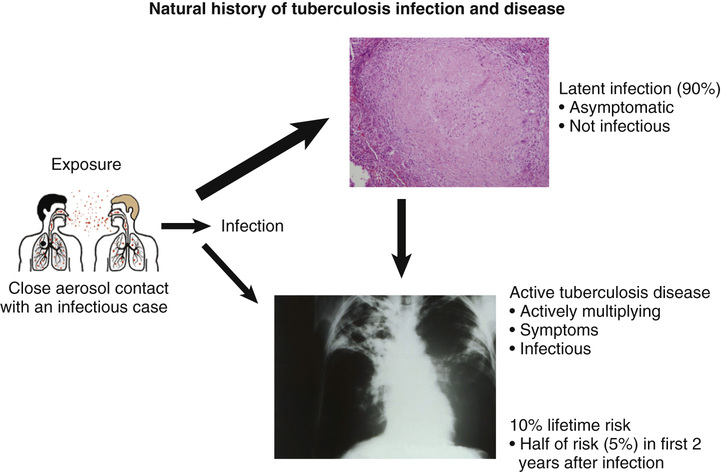

Caitlin Reed, Arzhang Cyrus Javan The patient should immediately be placed in airborne isolation because pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) is in the differential diagnosis for an immigrant with chronic cough and systemic symptoms. Avoiding nosocomial transmission of TB from patients with infectious active pulmonary disease is a priority. The patient should be given a surgical mask and placed in a single room with a closed door, preferably an airborne isolation room with negative pressure. Health care personnel should wear appropriately fitted N95 masks while caring for patients under evaluation for pulmonary tuberculosis. Without the night sweats and weight loss, the differential diagnosis of chronic cough is broad and includes common noninfectious etiologies such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, postnasal drip, and gastric esophageal reflux disease. However, this patient has significant constitutional symptoms, so we are concerned about more serious underlying diseases: pulmonary TB caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) infection such as Mycobacterium avium, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) presenting with an opportunistic infection, endemic fungal infections such as coccidioidomycosis or histoplasmosis, malignancy (especially because the patient smokes), chronic anaerobic lung abscess, interstitial lung disease, and rheumatologic diseases such as sarcoidosis and granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA). A chest radiograph (CXR) is an important initial diagnostic test in evaluating chronic cough with unintentional weight loss and fevers. A sputum specimen for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) smear microscopy and culture should be obtained every 8 to 24 hours for a total of three specimens. A nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) should be ordered on at least the first sputum specimen. NAAT tests include but are not limited to TB polymerase chain reaction (PCR), Amplicor MTB, Amplified Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Direct test, and Cepheid GeneXpert. These tests are more sensitive and specific than AFB sputum smears. All patients under evaluation for TB should be tested for HIV. Basic laboratory testing should include a complete blood count (CBC), electrolyte panel, liver function tests (LFTs), and screening for viral hepatitis. This patient has unexplained polyuria and polydipsia, which should be evaluated with a glycosylated hemoglobin (HgbA1C) for diabetes screening. Moreover, diabetes is one of several risk factors for progression from latent TB infection to active TB disease. Additional diagnostic workup should be considered based on epidemiologic risk factors and initial findings. For example, if the CXR is abnormal and the patient has lived in the desert Southwest, serology for the endemic fungal infection coccidioidomycosis (“Valley Fever”) should be ordered. Malignancy is an important consideration, especially as the patient is a smoker; however, TB must be evaluated before considering procedures such as bronchoscopy with biopsy or computed tomography (CT)-guided biopsy of a lung mass. A CT scan of the chest should be ordered if malignancy is suspected after initial workup, and sputum cytology is a noninvasive test that can be obtained as part of the evaluation. Figure 40.1 shows the natural history of TB infection. Persons who are exposed to TB from a coughing source patient with active pulmonary TB inhale bacilli into their lungs. In most patients, the immune response contains the infection in walled-off granulomas. The person is asymptomatic and noninfectious; this state is called latent TB infection (LTBI). Bear in mind that the large majority, about 90%, of persons with LTBI never progress to active TB disease. In the United States, the majority of patients who do develop active TB disease were initially infected years and often decades prior; this is because of TB’s uniquely long latent period. Active TB disease may occur because of waning of immune control of TB infection as a result of aging or other medical conditions; this presentation is referred to as reactivation TB. A small proportion of TB patients develop active disease soon after primary infection. This is more likely to occur among immunosuppressed patients, such as those with HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). These tests are screening tests for TB infection but do not distinguish latent TB infection from active TB. These tests are of limited utility in evaluating patients suspected of having active TB. When evaluating for active TB, it is crucial to pursue diagnostic tests, including AFB smear, culture, and nucleic acid amplification tests such as TB PCR, on specimens collected at the site of disease.

A 54-Year-Old Male With Chronic Cough and Weight Loss

What infection control measure should be immediately instituted?

What is the differential diagnosis of chronic cough with constitutional symptoms?

What initial tests should be ordered?

What is the difference between latent TB infection and active TB disease?

What is the utility of a tuberculin skin test or an interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA), such as QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube test, in a patient suspected of having active pulmonary TB? How do these screening tests work?

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

40 A 54-Year-Old Male With Chronic Cough and Weight Loss

Case 40