Monisha Bhanote, Daniel Martinez Upon more detailed questioning, he reports a 20-pound weight loss over the past 2 months and a 50-pack-year history of smoking (2 packs per day for 25 years). On physical exam, his temperature is 37.2 °C (99 °F), blood pressure is 155/92 mm Hg, pulse rate is 110/min, respiration rate is 24/min, and oxygen saturation is 92% on room air. He appears anxious and in mild respiratory discomfort. There is no jugular venous distension or lymphadenopathy. On cardiac exam, he is tachycardic with no murmurs or extra heart sounds. On pulmonary exam, there is diffuse rhonchi and diminished breath sounds in the right lower lobe. There is digital clubbing but no cyanosis or peripheral edema. Initially the case seems to be describing a general COPD exacerbation treated with glucocorticoids and antibiotics. However, his symptoms worsened despite this treatment and he developed hemoptysis. A detailed history also discovered his weight loss and extensive smoking history. The exam was concerning for diminished breath sounds in the right lower lobe and digital clubbing. These are red flag signs and symptoms that suggest a more serious underlying pathology. Diagnoses to consider are pulmonary vasculitis, malignancy, or tuberculosis. Ultimately, a tissue biopsy of some sort is required to differentiate among the three. However, the initial workup includes basic labs and imaging directed toward evaluating abnormal physical exam findings. A complete blood count (CBC) and chest radiograph (CXR) are appropriate in this particular situation, and further imaging with a computed tomography (CT) scan may be necessary depending on the results. Pulmonary nodules are defined as solitary lesions less than 3 cm in greatest dimension completely surrounded by lung parenchyma. The differential diagnosis of a lung nodule can be divided into three main categories: malignancy, infection, and vascular (Table 35.1). TABLE 35.1 Differential Diagnosis of Solitary Pulmonary Nodules Pleural effusions are an accumulation of fluid within the parietal and visceral pleura. They can be either exudative or transudative. Exudative effusions are protein rich and seen secondary to inflammation of the pleural space, whereas transudative effusions are accumulations of fluid that is normal in consistency to the fluid already present within the pleural space but seen in volume overload state (see Table 35.2). Smaller effusions can have minimal physical findings; however, effusions larger than 1500 mL may have diminished breath sounds, egophony, and dullness to percussion. Pleural fluids can be analyzed through percutaneous removal (thoracentesis). Thoracentesis can be not only diagnostic but also therapeutic, as removal of the fluid increases space in the thoracic cavity, thereby relieving difficulty in respiration. According to Light’s criteria, a pleural effusion is likely exudative if at least one of the three ratios exists. TABLE 35.2 Causes of Pleural Effusions Thoracentesis fluid should be submitted for the following laboratory tests: cell count with differential, glucose, adenosine deaminase and acid-fast bacilli stain/culture (if tuberculosis is suspected), anaerobic and aerobic bacterial cultures (if infection is suspected), and cytology.

A 57-Year-Old Male With Shortness of Breath

What is concerning about this presentation, and how should you proceed?

What is the differential diagnosis for a solitary pulmonary nodule?

Malignancy

Infection

Vascular

Primary lung carcinoma

Granulomas/tuberculosis

Resolving infarctions

Metastatic carcinoma

Pneumonia

Rheumatoid nodules

Arteriovenous malformations

What are the basic types of pleural effusions?

Transudative

Exudative

Congestive Heart Failure

Malignancy (carcinoma, lymphoma, leukemia, mesothelioma)

Nephrotic Syndrome

Infection (bacterial pneumonia, fungal disease, parasites, tuberculosis)

Cirrhosis

Connective tissue disease (Churg-Strauss, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, Wegener granulomatosis)

Atelectasis

Post-CABG (Dressler syndrome)

Pulmonary Embolism

Pulmonary embolism

What additional testing should be performed on exudative effusions?

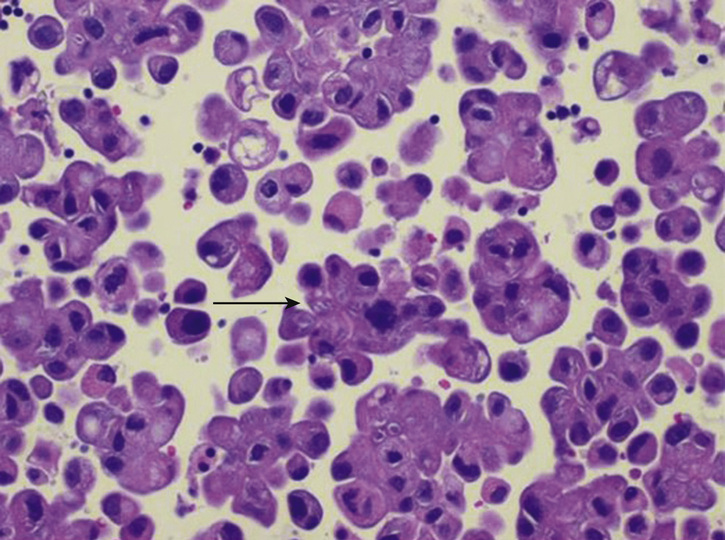

What are the common clinical and radiologic findings that may lead to a diagnosis of malignancy over nonmalignant causes?

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

35 A 57-Year-Old Male With Shortness of Breath

Case 35