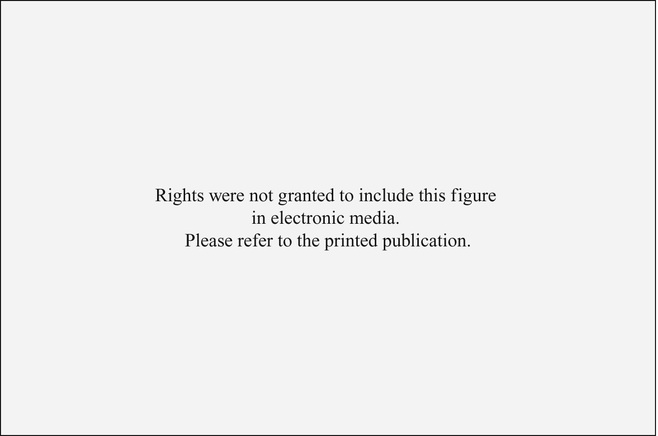

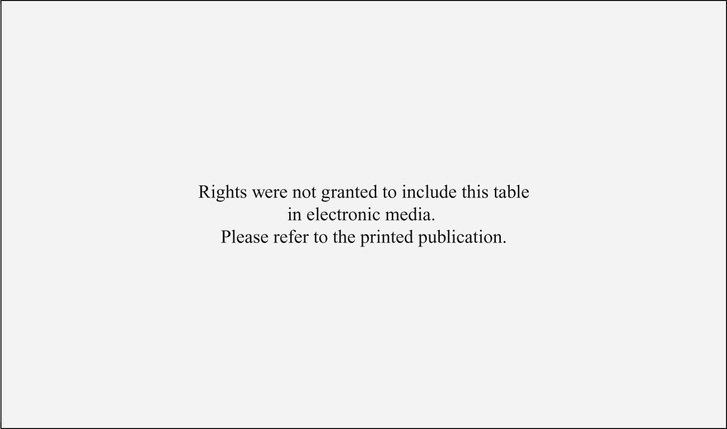

Andrew Morado, Raj Dasgupta, Ahmet Baydur Edema is accounted for by capillary permeability and the balance between hydrostatic and oncotic pressure (Fig. 21.1). Diffuse edema typically is a result of heart, kidney, or liver dysfunction. Systolic heart failure causes peripheral edema from increased hydrostatic pressure as a result of poor forward flow as left ventricular function deteriorates. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) causing oliguria or anuria arises from destruction of glomeruli resulting in decreased glomerular filtration rate and fluid retention. Alternatively, any of the many causes of nephrotic syndrome causing excessive loss of plasma proteins, especially albumin, can cause peripheral edema from loss of serum oncotic pressure within the vasculature. Finally, liver disease can cause edema via the underfill theory stating that vasodilation of the splanchnic circulation results in decreased blood flow to the kidneys. This stimulates the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and results in sodium retention, and water naturally follows. Hypoalbuminemia from impaired synthetic function also contributes to edema. When edema is confined to a single extremity, then systemic causes become less likely. Instead, consider local processes at the limb involved that may be the culprit. Cellulitis can cause edema because of local inflammation resulting in increased capillary permeability. Patients with history of trauma or surgery can suffer damage of the lymphatics causing retention of fluid. Additionally, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a common cause of unilateral edema, usually caused by vascular obstruction of venous return from the affected limb. Given the lack of trauma or surgery to the affected leg and no systemic signs of infection, DVT becomes our likely diagnosis. Risk factors for DVT are described by Virchow’s triad: hypercoagulability, injury to the vascular endothelium, and variation in blood flow. Any condition that affects these three parameters will predispose to development of a DVT. This includes pregnancy, malignancy, inherent disorders of coagulation, birth control, smoking, surgery, immobilization, and nephrotic syndrome. D-dimer levels in the serum and compression ultrasonography are primary modalities for diagnosing DVT. However, knowing the pretest probability of your presumed diagnosis is important as it determines the usefulness of your tests. The Wells score for DVT (see Table 21.1) helps stratify patients into low, moderate, or high risk based on clinical findings in the history or exam. For low-risk patients, a D-dimer is sufficient to exclude DVT, but for higher-risk patients, compression ultrasound becomes the diagnostic test of choice. Numerous inherited defects of coagulation have been identified and include factor V Leiden (most common), protein C/S deficiency, antithrombin 3 deficiency, antiphospholipid antibodies, and hyperhomocysteinemia. Testing for each can be time consuming and expensive with relatively low yield. Thus, exhaustive workup should be reserved for those with thrombi occurring at a young age, family history of clots, recurrent thrombosis, or atypical locations, especially arterial thrombi in the absence of predisposing risks. Traditionally, warfarin had been the standard of care for treatment of DVT, but with the advent of newer drugs including low molecular weight heparin, factor 10a inhibitors, and direct thrombin inhibitors, our arsenal is far more varied. Because we all love the coagulation cascade, Figure 21.2

A 34-Year-Old Female With Left Lower Extremity Edema

What are common causes of peripheral edema and the mechanism?

What are causes of unilateral peripheral edema?

What are risk factors for development of DVT?

How would you proceed with her care to make a diagnosis?

What inherited coagulopathies should be considered for recurrent DVT?

How should therapy be instituted for this patient?

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

21 A 34-Year-Old Female With Left Lower Extremity Edema

Case 21