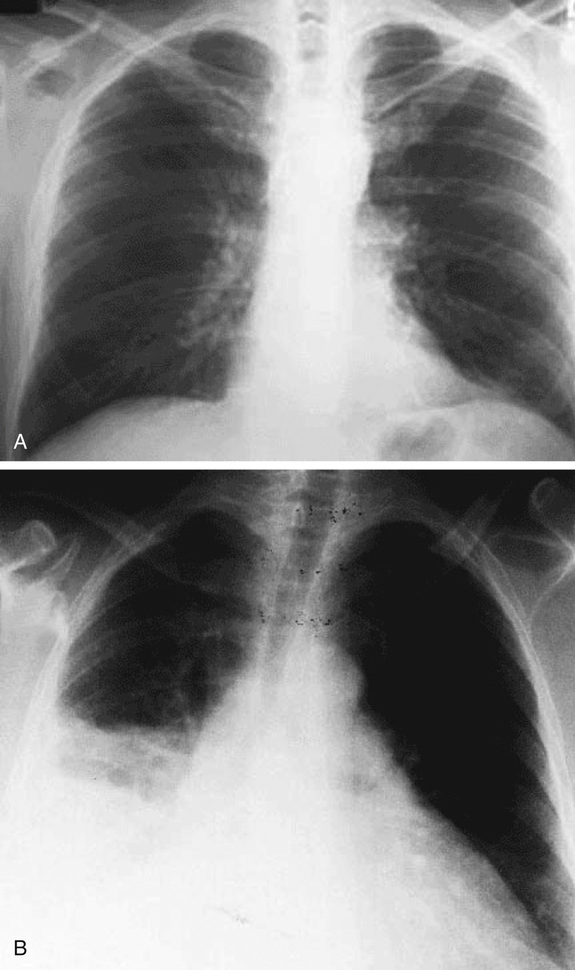

Arzhang Cyrus Javan, Andrea Censullo Cough is very commonly encountered in medical practice and has a broad differential diagnosis. To help narrow the differential, first determine the duration of cough. This patient has an acute cough (defined as <3 weeks), which is most often caused by a viral upper respiratory tract infection (URI) but can also be a presenting symptom in patients with pneumonia (infection of the lung parenchyma, i.e., the lower respiratory tract), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation, pulmonary malignancy, pulmonary embolism, or congestive heart failure (CHF)-related pulmonary edema. A subacute cough (3 to 8 weeks) is most commonly postinfectious in origin, whereas a chronic cough (>8 weeks) is most commonly caused by postnasal drip, asthma, or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Keep in mind that this is by no means an exhaustive list as the differential for cough is quite broad. Next, ask about symptoms associated with pneumonia. It is important to distinguish this relatively common and serious entity from the less common or less serious causes of cough. The classic symptoms of bacterial pneumonia are acute-onset cough, sputum production, dyspnea, chest pain (often pleuritic), and fever. Patients with pneumonia may also report nonpulmonary symptoms such as fatigue, sweats, headache, nausea, myalgias, and occasionally abdominal pain and diarrhea. Remember that the elderly often present with fewer of the classic symptoms just described. Asking about the presence and quality of sputum can help when formulating a strong differential. Purulent sputum (containing pus) can suggest pneumonia but is nonspecific and can also point toward COPD, bronchiectasis, lung abscess, and even a viral URI. Hemoptysis (bloody sputum) is commonly caused by viral bronchitis but should raise suspicion for cancer or tuberculosis in those with risk factors. Finally, ask about medication use because some patients develop a dry cough while taking angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. This 56-year-old male is presenting with an acute cough productive of purulent sputum, fevers, dyspnea, and pleuritic chest pain. These collective signs and symptoms point toward an infection and should place pneumonia at the top of your differential. There may be a considerable amount of overlap in the signs and symptoms of pneumonia and the other causes of acute cough, so important clues already gathered from the history must be used to help sort through the differential. He has no known history of COPD or CHF, so a COPD or CHF exacerbation would be highly unlikely. He lacks the chronic constitutional symptoms that would suggest an underlying malignancy. Pulmonary embolism (PE) is still on the differential as it too often manifests with dyspnea and pleuritic chest pain (Table 20.1). Although patients with PE can occasionally have fevers, the purulent sputum in this case makes this a less likely diagnosis. Viral URI is still on the differential but somewhat less likely because of the presence of dyspnea. By taking a thorough social history, you can determine a patient’s risk factors for unusual pathogens that may not be covered by a standard empiric antibiotic regimen. Any disorder that increases the risk of aspiration, including alcoholism, increases the risk for pneumonia caused by oral anaerobes and gram-negative enteric pathogens including Klebsiella pneumoniae. Tobacco smokers and those with COPD have an increased risk for pneumonia with Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Legionella species including L. pneumophila and, less commonly, Pseudomonas species. A travel history is important because some infections are geographically limited. Exposure to bat or bird droppings in the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys raises the possibility of pneumonia caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, whereas infection with Coccidioides immitis, another endemic fungi, occurs mainly in the southwest United States. Ask about a recent hotel or cruise ship stay that can increase the chance of an infection with Legionella. Emerging infectious diseases are also initially geographically limited, such as Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) (Arabian peninsula) and avian influenza (Asia). Tuberculosis (TB) is more likely in those who have lived in or traveled to an endemic region for TB and also in those who are homeless. Although rare, certain zoonotic organisms can cause pneumonia in humans. This list of pathogens includes Chlamydophila psittaci (bird exposures), Coxiella burnetti, the agent of Q fever (farm animals), and Francisella tularensis (rabbits). This is why it is always important to ask about animal exposures. If the history reveals risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), opportunistic pathogens such as Pneumocystis jiroveci (which causes Pneumocystis pneumonia, also known as PCP) in addition to Mycobacterium tuberculosis should be added to your differential. With that said, S. pneumoniae is still the leading cause of pneumonia in those with HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Unfortunately, no cause is found in approximately half of the patients diagnosed with pneumonia in the United States. There are signs of lung consolidation on physical exam, which further supports a diagnosis of pneumonia. All patients with suspected pneumonia should have a chest radiograph (CXR), ideally a posterior-anterior (PA) and lateral view. This patient has a consolidation in the right lower lobe, thus solidifying the diagnosis of pneumonia. Although no one pattern on CXR is specific for any one pathogen, the general radiographic appearance can sometimes provide the clinician with important clues as to the cause of the pneumonia. Lobar consolidation, as seen in this patient, points toward (but does not equal) infection with a “typical” bacterial pathogen. In contrast, an interstitial pattern on chest radiograph is more often associated with “atypical” pathogens. The typical bacterial pathogens are S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and, in certain patient populations, the gram-negative bacilli and S. aureus. Mycoplasma, Chlamydophila, Legionella, as well as the respiratory viruses comprise the atypical category. The atypical organisms are distinguished from the typical by the fact that they generally cannot be visualized on Gram stain or cultured via standard media. The history cannot be used to definitively differentiate between the typical and atypical pathogens. With that said, the typical pathogens generally cause a more acute presentation, whereas the atypicals, excluding Legionella, generally present with a more indolent course, often in younger patients.

A 56-Year-Old Male With Acute Cough and Fever

What are some important initial questions to ask in a patient who presents with a cough?

What is at the top of your differential?

How does the information gathered from taking a thorough social history influence your initial evaluation and management of patients with suspected pneumonia?

What diagnostic test should you perform next?

Does this CXR help narrow your differential?

What are the typical and atypical pathogens? Why does it matter to distinguish them?

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

20 A 56-Year-Old Male With Acute Cough and Fever

Case 20