Chapter 32 Tumors and related lesions of the sebaceous glands

Ectopic sebaceous glands

Clinical features

Sebaceous glands are normally found in association with a hair follicle. However, at several mucosal sites, they may develop independently, presenting as small 1–3-mm yellow to white papules (Fordyce spots), which can be accentuated when the mucosa is stretched.1 Lesions of the oral cavity commonly present on the vermilion border of the lip and the buccal mucosa.2,3 On the vulva, Fordyce spots affect the medial aspect of the labia majora while in males the glans penis is involved.4 Prevalence varies, but some large studies place the incidence of oral lesions at greater than 25%.2,3,5 Incidence increases with age since Fordyce spots are not commonly seen in infants.2,3 They are of little consequence and likely represent a normal physiological variant since such a large proportion of the adult population is affected.1 Rarely, lesions on the lip become a cosmetic nuisance.6

Similar tiny papules are sometimes seen on the areola of the female breast where they are known as Montgomery’s tubercles.7–10 These may be associated with vellus hairs or lactiferous ducts, and occasionally in adolescence they are complicated by the development of a small breast lump, which discharges thin secretions.11 Such lesions tend to resolve spontaneously. Sebaceous hyperplasia of the areola has been reported in both women and men (see below), but its relationship to Montgomery’s tubercles (if any) is unclear.12

Occasionally, ectopic sebaceous glands have been identified in the esophagus, gastroesophageal junction, uterine cervix, vagina, sole of the foot, thymus, and tongue.13–23 Rarely, these lesions have been described as extensively involving the esophagus.

Sebaceous hyperplasia

Clinical features

Sebaceous hyperplasia is a common condition which is frequently clinically misdiagnosed as basal cell carcinoma. It most often presents on the face of older adults, particularly males (Fig. 32.1).1 Lesions are, however, occasionally encountered in children.2,3 The forehead and cheeks are predominantly affected and occasionally diffuse facial involvement occurs (Fig. 32.2).1,4 Other less common sites include the chest, ocular caruncle, penis, scrotum, and vulva.5–11 A linear variant presenting on the penis has been described.12

Fig. 32.1 Sebaceous hyperplasia: multiple lesions are present on the cheek. Note the central umbilication.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Lesions – which may occur individually, in groups, or as a sheet of papules – present as yellowish, dome-shaped asymptomatic papules 1–2 mm in diameter.1,13 Larger variants measuring 1.0 cm or more in diameter are occasionally seen (giant solitary/senile sebaceous hyperplasia).14–17 The papule is umbilicated, and individual lobules growing out from the center can often be identified with a hand lens. Recently, distinctive dermatoscopic features including cumulus sign, crown vessels, and milia-like cysts have been described.18,19

Rarely, postpubertal sebaceous hyperplasia occurs, either as an isolated phenomenon or more rarely in association with anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia.20,21 Familial cases, sometimes with early onset, have also been described.22–24 Sebaceous hyperplasia is significantly increased in transplant patients, particularly in males following renal transplantation, and this may be related to therapy with cyclosporin A.25–28 A case in an immunosuppressed patient with Senear-Usher syndrome (pemphigus erythematosus) has recently been reported.29

Ectopic sebaceous glands with associated hyperplasia have been described in the oral mucosa and on the areola where lesions may be bilateral (areolar sebaceous hyperplasia).30–39

Pathogenesis and histological features

Although sebaceous development is profoundly affected by androgens, their mode of action in sebaceous hyperplasia has not yet been determined.40 Since these lesions do not regress, it is unclear that they truly represent hyperplasia, which is a reversible phenomenon. Nonetheless, the name sebaceous hyperplasia is certainly indicative of a well-defined clinicopathologic entity.

Studies have indicated that overexpression of the mEDA-A1 splice variant of EDA which encodes ectodysplasin, a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) ligand family, induces sebaceous hyperplasia in transgenic mice.41 This transcription factor is involved in skin adnexal development, acting through the nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB) and JNK pathways.41,42 Mutations in EDAcause X-linked anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia.43 The relevance of this finding to human sebaceous hyperplasia remains to be determined, although interestingly and perhaps incongruously, sebaceous hyperplasia as mentioned above has been reported in the setting of anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia.20,21

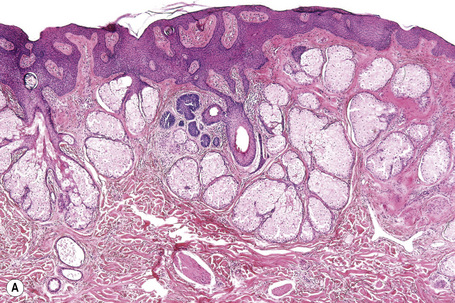

In solitary papules, the individual gland is hyperplastic and situated higher in the dermis than normal (Fig. 32.3).44 Individual lobules are increased in number but are not appreciably different in size compared with normal sebaceous glands. The individual lobules drain into a central duct, which is often associated with a hair follicle, through single or multiple follicular infundibula (Figs 32.4, 32.5).45 In confluent lesions, multiple sebaceous glands are similarly affected. In both variants the dermis is normal, except for a variable degree of elastosis.

Fig. 32.3 Sebaceous hyperplasia: scanning view showing sebaceous glands grouped around a cystic infundibulum.

Oral sebaceous hyperplasia is not associated with a hair follicle and the lobules empty into a single duct that opens directly onto the mucosal surface.31,38

Sebaceous hyperplasia overlying a benign fibrous histiocytoma (dermatofibroma) has been documented.46,47

Nevus sebaceus

Clinical features

Nevus sebaceus (Jadassohn, organoid nevus) is not uncommon and often presents at birth although it usually does not cause the patient to seek medical attention until the second to fourth decades.1–3 Lesions have been described in up to 0.3% of neonates.4 The sex distribution is equal.

Nevus sebaceus is single, round or oval, well circumscribed and usually measures 1–6 cm in greatest dimension. It commonly affects the head and neck, particularly the scalp where it presents as a yellowish, flat or mamillated patch of alopecia (Fig. 32.6). Other sites of predilection include the forehead, temples, around the central face, and behind the ears.1–3 Rarely, lesions have been documented at other sites including the trunk, breast, limbs, oral cavity, external auditory canal, and perianal region.3–8 It becomes rather warty during childhood and in adolescence shows marked enlargement with development of a waxy surface under the influence of pubescent hormonal stimulation.3 In adulthood, any further change is likely to be due to the development of a range of usually benign but sometimes malignant tumors of variable differentiation (Fig. 32.7).1–3 Less frequently, nevus sebaceus presents as a linear lesion, often behind the ear.2 Sometimes the lesion is very extensive and a zosteriform variant has been noted. 9 Few cases of familial nevus sebaceus showing paradominant transmission have been described.10–16

Fig. 32.7 Nevus sebaceus: in this example, basal cell carcinoma has developed in a nevus sebaceus.

Courtesy of J.C. Pascual, MD, Alicante, Spain.

Very rarely, congenital nevus sebaceus is associated with other abnormalities, particularly neurological symptoms.17 Involvement tends to be linear and frequently parasagittal with a wide distribution on the head and scalp, and sometimes it extends to the neck and shoulder.18,19 Most such cases are classified as linear nevus sebaceus syndrome which presents with a triad of nevus sebaceus, seizures, and mental retardation.9,18,19 In practice, however, seizures and mental retardation are not regularly present. Ocular abnormalities are common and other organ systems may also be affected.19 The seizures are sometimes intractable to medical treatment and may require surgical intervention.20 Reported complications include unilateral megalencephaly, hamartomatous intracranial mass, hemimegalencephaly, cerebral arteriovenous malformation, desmoplastic neuroepithelial tumor, hemifacial asymmetry, complex conjunctival colombomas or choristomas, corneal dermoid, macular and optic nerve hypoplasia, optic glioma, nonparalytic strabismus, partial oculomotor palsy, microphthalmia, retinal detachment, sensorineural deafness, inner ear malformation with hearing loss, rickets, uvula bifida, premature tooth eruption, cleft secondary palate, and diffuse pulmonary angiomatosis.21–40 Extensive surgical resection with reconstruction may sometimes be required.41 This condition forms part of the Schimmelpenning syndrome (Schimmelpenning-Feuerstein-Mims syndrome, organoid nevus phakomatosis), which represents a distinct clinicopathological subset of the epidermal nevus syndrome.42–44 More recently, SCALP syndrome has been described consisting of the combination of nevus sebaceus, central nervous system malformations, aplasia cutis congenita, limbal dermoid, and pigmented nevus.45

Nomenclature and classification schemes for the epidermal nevus syndrome are complex, with overlapping entities and variable associated defects. Nevus sebaceus can coexist with other epidermal nevi, including verrucous epidermal nevus, possibly representing a continuum of manifestations.46

Other rare associations, not clearly syndromic and perhaps incidental, include melorheostosis, mediastinal lipomatosis, and familial retinoblastoma.47–49 Nevus sebaceus has also been reported in a child with nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome.50 A nevus sebaceus was reported as a paired phacomatosis pigmentokeratotica with speckled lentiginous nevus of the abdominal wall in which embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma arose in one exceptional case.51

Pathogenesis and histological features

Deletion of the PTCH gene has been reported in nevus sebaceus.52 The PTCHpathway is involved in cutaneous patterning and development.53–56 This finding has some relevance, particularly in the context of the disordered epithelium and appendageal structures characteristic of this lesion. However, such PTCH deletions have not been confirmed by others and additional research is necessary.57 A mouse skin graft model with nevus sebaceus-like lesions which appear to have been induced by aberrantly transplanted dermal fibroblasts has been described.58

Nevus sebaceus is a complex lesion comprising abnormalities of the epidermis, hair follicle, and sebaceous and sweat glands. The epidermis may be acanthotic or papillomatous and foci of abortive hair papillae-like proliferations are commonly seen (Figs 32.8, 32.9). The epithelium in older lesions sometimes contains foci of pale-staining glycogen-rich cells, suggesting outer root sheath differentiation reminiscent of trichilemmoma.

Sebaceous glands are variably hyperplastic and excessive, diminished in number or even absent (Fig. 32.10). In early infancy the sebaceous glands often show a transient enlargement under the lingering influence of maternal hormones, but they then diminish in size until adolescence when they undergo marked proliferation. This is followed by a tendency to involution with increasing age. Virtually all lesions show irregularities of morphology and distribution of sebaceous glands. Commonly, they are located at an abnormally high level within the dermis, sometimes communicating directly with the surface of the epidermis (Fig. 32.11). Often they appear unrelated to a hair follicle. A punched-out defect at the periphery of a lobule is occasionally seen, presumably representing coalescence of several mature lipid-laden sebaceous epithelial cells.

Fig. 32.11 Nevus sebaceus: in this field, the sebaceous gland communicates directly with the epidermis.

Nevus sebaceus is frequently complicated by development of a variety of other benign cutaneous neoplasms including syringocystadenoma papilliferum, trichoblastoma-like lesions, trichilemmoma, sebaceous neoplasms, keratoacanthoma-like lesions, viral wart, seborrheic keratosis, giant cutaneous horn, spiradenoma, pilar leiomyoma, nodular hidradenoma, dermal lipoma, banal melanocytic nevus, combined blue and speckled lentiginous nevus, infundibuloma, apocrine cystadenoma, tubular apocrine adenoma, syringoma, and extramedullary hematopoiesis.1,59–68 A recent large study has shown that syringocystadenoma papilliferum and trichoblastoma-like proliferations are the most commonly encountered lesions (both 5%) while trichilemmoma and sebaceoma are present in 2–3% of cases, with other lesions being less frequent (Figs 32.12–32.16).68 Malignant tumors are much less often seen and include basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, sebaceous carcinoma, eccrine porocarcinoma, dermal leiomyosarcoma, apocrine carcinoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, and trichilemmal carcinoma.1,69–80 Historically, basal cell carcinoma was thought to represent the most common malignant neoplasm arising in association with nevus sebaceus with incidences reported as high as 20%.1–3 Recent studies, however, indicate that the majority of cases of basal cell carcinoma arising in nevus sebaceus are more accurately classified as benign trichoblastoma-like lesions, although authentic basal cell carcinoma is occasionally seen.68,81,82 Both benign and malignant secondary lesions are more commonly encountered in adults, although children may also rarely be affected.69,82–84 Nonetheless, the currently perceived scarcity of malignancy in childhood nevus sebaceus has called into question the necessity of early prophylactic excision.85,86 Nevus sebaceus not uncommonly shows multiple tumor-like proliferations. Frequently, these defy precise classification.87

Steatocystoma and sebocystomatosis

Clinical features

Steatocystoma multiplex (sebocystomatosis), characterized by autosomal dominant inheritance, usually presents in adolescence.1,2 Although the sternal region is commonly affected in the male, and the axillae and groins in the female, lesions (which are invariably multiple) may involve most of the upper trunk and face. More localized variants presenting on the face, scalp, nose, and vulva have been described.3–12 A linear form is very infrequently encountered.9,13,14

Early small dome-shaped lesions are rather translucent, changing to a yellowish color with age (Figs 32.17, 32.18). Puncta are not obvious, but comedones are often associated features.15 Spontaneous rupture of the cysts sometimes results in steatocystoma multiplex suppurativum characterized by inflammation and scarring reminiscent of acne conglobata.16–18

Fig. 32.17 Steatocystoma multiplex: numerous small yellowish papules are present on the chest.

By courtesy of R.A. Marsden, MD, St George’s Hospital, London, UK.

Rarely reported associations include natal teeth, hidradenitis suppurativa, bilateral preauricular sinuses, multiple trichoblastomas, familial hypobetalipoproteinemia, cerebellar ataxia, intracranial dermoid, LEOPARD syndrome, Alagille syndrome and Lowe (oculocerebrorenal) syndrome.19–26 Spherulocystic disease (myospherulosis) has also been described.27

Steatocystoma simplex, in which patients present with a solitary lesion, shows an equal sex incidence and usually affects adults.28 The cysts are asymptomatic and well circumscribed. They are particularly found on the face or neck, chest, axillae, and arms.29 Involvement of the oral cavity and ocular caruncle has been described, albeit uncommonly.30–33

Rarely, steatocystoma multiplex and eruptive vellus hair cysts have been described in the same patient.34–38

Pathogenesis and histological features

Mutations in KRT17 (encoding Keratin 17), which is expressed in the nail matrix, hair follicles, and sebaceous glands, have been documented in families with steatocystoma multiplex.39–42 Similar mutations have also been described in pachyonychia congenita type II (Jackson-Lawler syndrome).43,44 These shared mutations offer a pathogenetic basis for occasional cases of these two conditions occurring in the same individual.45–49 The presence of a mutation in KRTI7, within a single family cohort can lead to affected members with only pachyonychia congenital type II or only steatocystoma multiplex.35 Mutations in KRTI7 have not been described in steatocystoma simplex.

It is of some relevance that eruptive vellus hair cysts have also been described in association with pachyonychia congenita since a number of authors believe that there is significant morphological overlap between eruptive vellus hair cyst and steatocystoma.36,50–53 Although eruptive vellus hair cysts express keratin 17, steatocystoma also expresses keratin 10 and thus other authorities believe that the two conditions can be clearly distinguished.43,54 Their exact relationship (if any) therefore remains to be determined.

Steatocystoma probably represents a true sebaceous cyst since its lining mirrors the point where the sebaceous duct enters the hair follicle.55 The thin-walled dermal cyst is usually collapsed and folded, appearing empty except for sebaceous debris and rarely a hair fragment (Figs 32.19, 32.20).28 The lining typically comprises a few cells forming stratified squamous epithelium and maturing into a homogeneous, undulating eosinophilic cuticle without the formation of a granular layer (Fig. 32.21).29 Sebaceous glands are an almost invariable feature, either within the squamous lining itself or adjacent to it.

The lesions of steatocystoma multiplex and simplex are histologically indistinguishable.

Sebaceous adenoma

Clinical features

Sebaceous adenoma is rare and frequently misdiagnosed clinically as a basal cell carcinoma. It presents most often in older people (mean age 60 years) as a tan, pink-to-red or yellow papulonodule measuring approximately 0.5 cm in greatest dimension.1–3 Occasionally, it has a polypoid appearance.2 The face (particularly the nose and cheek) and scalp are most often affected (Figs 32.22, 32.23).2 Less commonly affected sites include the ear and medial canthus and occasionally lesions have been described on the trunk, leg, arm, and penis.2,4,5

Fig. 32.22 Sebaceous adenoma: note the yellow papule on the cheek of this elderly patient.

By courtesy of R.A. Marsden, MD, St George’s Hospital, London, UK.

Fig. 32.23 Sebaceous adenoma: this example is dome-shaped and has a slightly scaly surface.

By courtesy of R.A. Marsden, MD, St George’s Hospital, London, UK.

Sebaceous adenoma forms part of the spectrum of the Muir-Torre syndrome, particularly those that arise outside the head and neck region.6 Occasional reports have documented its presence in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).7,8 Rarely, it may develop intraorally, possibly in association with Fordyce papules.3,9–15 Sebaceous adenoma has rarely been described in the submandibular and parotid glands.16–18

Pathogenesis and histological features

Recently, inactivating mutations in LEF1, the gene encoding a transcription factor in the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, have been documented in a subset of sebaceous adenomas.19 This pathway is involved in fate selection of follicular stem cells to adopt sebaceous differentiation and may also directly promote tumorigenesis.20,21 The hedgehog and c-Myc pathways may also be involved in tumorigenesis.22,23

The tumor is multilobulated and sometimes appears to replace the surface epithelium (Fig. 32.24).1,2 Individual lobules, often surrounded by a collagenous pseudocapsule, mirror the structure of a normal sebaceous gland. At the periphery are a variable number of layers of small germinative cells with round or oval vesicular nuclei and scanty cytoplasm.2,3 This increased number of basaloid or germinative cells allows separation from sebaceous hyperplasia, which has at most two layers of basal cells.24 The basaloid cells blend with the usually more centrally located mature sebaceous cells, which are much larger and have pale-staining foamy cytoplasm and central crenated hyperchromatic nuclei.24,25 Occasionally, peripheral palisading is a feature.2 Some lobules show cystic degeneration and others appear to communicate directly with the surface epithelium. By convention, more than half of the lobule in sebaceous adenoma is composed of mature sebaceous cells.24

Sometimes, giant sebaceous adenomas are encountered which may show increased mitotic activity in the basaloid cell component (Figs 32.25, 32.26). This should not be interpreted as implying malignant potential.

The intervening dermis may contain a chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate including lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells.26 An overlying cutaneous horn has been described.27

Sebaceous epithelioma

Few terms have caused as much confusion in dermatopathology as sebaceous epithelioma. This tumor has been variably recognized as a distinct lesion, as a variant of sebaceous adenoma, as an intermediate stage between sebaceous adenoma and basal cell carcinoma, and as a synonym for basal cell carcinoma with sebaceous differentiation. Troy and Ackerman introduced the term sebaceoma to help clarify this morass and proposed that the term sebaceous epithelioma be abandoned.1 Sebaceoma is clearly defined and distinguishable from sebaceous hyperplasia, sebaceous adenoma, and sebaceous carcinoma. Over time, use of sebaceous epithelioma as a diagnostic term has declined. The publications that have documented tumors described as sebaceous epithelioma have illustrations that are clearly not those of basal cell carcinoma with sebaceous differentiation and are indistinguishable from the description of sebaceoma.2–5 While we have sympathy with the view of Dinneen and Mehregan that ‘the term sebaceous epithelioma has merit for historical reasons and because the tumor can be locally destructive’ we believe that its continued use will only perpetuate the confusion in the literature.5 Sebaceoma appears to be established as the diagnostic terminology of choice for this tumor and, as in the third edition, we have adopted the term sebaceoma and no longer recognize sebaceous epithelioma as an entity. The alternative term sebomatricoma, which includes sebaceous adenoma and sebaceoma as opposite ends of a spectrum of benign sebaceous tumors, has not received significant support in the literature.6

Sebaceoma

Clinical features

Sebaceoma presents as a yellow-to-orange or flesh-colored papule, nodule or tumor measuring approximately 1–3 cm in diameter (Fig. 32.27).1–7 A giant variant measuring up to 6.0 cm in greatest dimension has also been described.2,8 The tumor presents more often in females (4:1) and, while a wide age range may be affected (29–87 years), the majority of patients are in the sixth to ninth decades. Lesions predominantly affect the face and scalp although a single report has described a case developing on the chest.4 Sebaceoma arising in continuity with a seborrheic keratosis has been documented and some examples have arisen within nevus sebaceus.2,3,9 Importantly, sebaceoma may reflect associated Muir-Torre syndrome.4,5,10

Fig. 32.27 Sebaceoma: yellowish nodule on the forehead of an elderly patient.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Histological features

Sebaceoma is centered in the dermis and only rarely affects the subcutaneous fat (Figs 32.28, 32.29).1 Epidermal involvement is often present. It consists of multiple variably sized, discrete nodules, symmetrically distributed and separated by dense eosinophilic connective tissue (Fig. 32.30).1–4 The nodules are composed of an admixture of basaloid cells and mature sebocytes lacking an organized lobular architecture.1 Peripheral nuclear palisading and cleftlike spaces separating the tumor nodules from the adjacent stroma are absent.1

Fig. 32.29 Sebaceoma: the tumor is composed of multiple lobules separated by connective tissue septa

Fig. 32.30 Sebaceoma: (A) scanning view showing conspicuous cyst formation; (B) high-power view of cysts.

The basaloid cells are small and uniform with minimal indistinct cytoplasm and round to oval nuclei, sometimes containing small nucleoli (Fig. 32.31). There is no nuclear pleomorphism and mitotic activity is generally sparse, although as with other basaloid cutaneous neoplasms (e.g., pilomatrixoma) it can sometimes be prominent. The sebaceous cells appear mature with eosinophilic bubbly cytoplasm and scalloped nuclei, but this process is usually distributed in multiple pockets throughout the proliferation rather than being centralized, as seen in sebaceous adenoma. Duct formation is frequently present and cysts containing sebaceous debris lined by an eosinophilic cuticle are often present within the nodule or at it edges (Figs 32.32, 32.33). Focal glandular differentiation with apocrine features has been noted on rare occasion.11,12 While holocrine secretion is regularly present, tumor necrosis in the basaloid component is not a feature.

Fig. 32.33 Sebaceoma: this is a scanning view of a rare cystic variant showing central degenerative features.

Occasional tumors may show superficial elements reminiscent of seborrheic keratosis or verruca vulgaris.2 Sebaceomas with carcinoid-like, reticulated, cribriform, and rippled or Verocay body-like features have also been described (Fig. 32.34).6,7,13–15

Differential diagnosis

Sebaceoma can be distinguished from sebaceous adenoma in which a lobular architecture with distinct and regular maturation (mimicking the normal sebaceous gland) is typically present. Sebaceous adenoma generally presents as a solitary nodular lesion in the superficial dermis, frequently replacing the overlying epidermis in whole or in part. It should be noted, however, that focal sebaceous adenoma-like features may sometimes be seen in a background of more typical sebaceoma.2 In such instances, the final diagnosis of sebaceous adenoma or sebaceoma may well be arbitrary. Of more importance is distinction from well-differentiated sebaceous carcinoma and recognition that the lesion could represent a cutaneous marker of Muir-Torre syndrome.

Sebaceoma should not be confused with basal cell carcinoma showing sebaceous differentiation which first and foremost is clearly a basal cell carcinoma showing peripheral palisading and cleft formation and in which the sebaceous differentiation is merely an incidental finding. Immunohistochemistry using EMA and D2–40, which are expressed by sebaceoma, and Ber-EP4, which labels basal cell carcinoma, may be helpful in limited biopsies, but the distinction can usually be made morphologically in intact specimens.16,17

Sebaceoma should also be differentiated from trichoblastoma with sebaceous differentiation.4 This latter tumor invariably shows focal hair germ differentiation, and papillary mesenchymal bodies are often evident. Peripheral nuclear palisading and stromal induction are also generally present.

When sebaceoma was originally defined, the authors intended it to replace the confusing term sebaceous epithelioma and to clearly define a novel entity distinct from both sebaceous adenoma and basal cell carcinoma with sebaceous differentiation.1 Others have proposed an alternative term, sebomatricoma, to include lesions previously designated sebaceoma, sebaceous epithelioma, superficial epithelioma with sebaceous differentiation, the sebaceous neoplasms associated with Muir-Torre syndrome, and those arising in nevus sebaceus.18 This alternative designation has not received support in the subsequent literature. Sebaceoma has become a widely adopted and useful diagnostic category. We agree that the term of sebaceous epithelioma is confusing and should no longer be used. Of utmost importance is recognition that a variety of benign sebaceous lesions with variable architecture and proportion of basaloid cells form the benign end of the Muir-Torre spectrum. Sebaceoma represents a more cellular and less architecturally organized variant (Fig. 32.35). Recognition of this cellularity is important to avoid confusion with sebaceous carcinoma. The term sebaceoma clearly recognizes this increased cellularity as benign.

Superficial epithelioma with sebaceous differentiation

Clinical features

Superficial epithelioma with sebaceous differentiation is a rare tumor, with less than 20 cases having been documented.1–10 Most often, it presents on the face.1–3 Two cases, however, have been described on the back and a single patient with multiple lesions involving the face, axilla, trunk, and thigh has been reported.4–6 Lesions are usually 1 cm or less in diameter but cases of up to 2 cm have been encountered.4 They present as flesh-colored or yellow-to-brownish papules, nodules or plaques. The age distribution is wide (38–79 years) but the mean age is 60 years.4 There is no clear gender predilection.8

The relationship of this tumor to Muir-Torre syndrome is unknown although one patient has had a family and personal history of esophageal and colon carcinoma.1 Recurrences following local excision have not been described.4

Histological features

The tumor is characterized by a sharply defined and well-circumscribed, platelike epidermal growth with elongated, thickened rete ridges that anastomose in a reticular pattern (Fig. 32.36).1 Merging with the more superficial keratinocytes is a cytologically bland basaloid cell population in which are admixed mature sebocytes, singly and in clusters.1 Mitotic activity may be evident and is sometimes brisk, but cytological atypia is not a feature.1 Ductal differentiation and keratin-filled cystic spaces are also present, and occasionally squamous eddies are a feature.1,4 Melanin pigmentation has been described.1 Peripheral palisading is not a feature and cleftlike spaces separating the tumor from the adjacent dermal connective tissue are absent.

Differential diagnosis

Superficial epithelioma with sebaceous differentiation should be distinguished from follicular infundibulum tumor. The latter is also characterized by a platelike epithelial proliferation suspended from the epidermis. However, the tumor trabeculae are characteristically thin, vacuolated, and often surrounded by a thickened eosinophilic basement membrane. In addition, follicular infundibulum tumor does not contain keratin-filled cysts or generally show sebaceous differentiation, although a single published case showed features of both tumors.11

Seborrheic keratosis with sebaceous differentiation also enters the differential diagnosis.9 This lesion, however, shows the features of an acanthotic variant of seborrheic keratosis with only small numbers of mature sebaceous cells scattered randomly throughout the epithelium.

A single case reported as reticulated acanthoma with sebaceous differentiation has been reported, with the squamous portion descending from the surface epithelium and showing a reticulated pattern.12 This lesion may fall within the spectrum of superficial epithelioma with sebaceous differentiation or seborrheic keratosis with sebaceous differentiation.

Sebomatricoma

To overcome this problem, Troy and Ackerman introduced the term sebaceoma which clearly described a tumor distinguishable from sebaceous hyperplasia, sebaceous adenoma, sebaceous carcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma with sebaceous differentiation.1 They recommended that the term sebaceous epithelioma be abandoned. In a similar vein, Sánchez Yus’s group proposed the term sebomatricoma to describe a spectrum of tumors ranging from sebaceous adenoma to sebaceoma.2–4 Although this has some merit, since sebaceous adenoma and sebaceoma do show an element of overlap and may both be associated with Muir-Torre syndrome, the term sebomatricoma has not received great support in the subsequent literature. In addition, the unusual benign sebaceous neoplasms associated with Muir-Torre syndrome were also included in this definition. The issue was a little clouded, however, since the authors also recommended inclusion of superficial epithelioma with sebaceous differentiation and sebaceous neoplasms arising within nevus sebaceus.4 In addition, this term would group sebaceous neoplasms clearly associated with the Muir-Torre syndrome and lesions such as follicular infundibulum tumor that can rarely show sebaceous differentiation but probably have no connection with the Muir-Torre syndrome. As a spectrum, this grouping may not have clinical utility.5

Basal cell carcinoma with sebaceous differentiation

Clinical features

Basal cell carcinoma with sebaceous differentiation is exceedingly rare, few cases having been published with even fewer photomicrographs.1–4 Despite this fact, the entity is commonly cited in reviews.5,6 It arises in the distribution expected for basal cell carcinoma, with the most common site being the face. Lesions are sometimes multiple.2,3 Its behavior appears no different from other basal cell carcinomas.

Pathogenesis and histological features

It is not clear whether basal cell carcinoma with sebaceous differentiation forms part of the spectrum of the Muir-Torre syndrome. Some authors have reported an association with internal malignancy, but diagnostic criteria within this family of neoplasms have evolved significantly since that report.3 In addition, since traditional basal cell carcinomas are associated with mutations in patched (PTCH1), p53, and BAX (bcl-2 associated X-protein) and not the genetic defects in DNA mismatch repair seen in the Muir-Torre syndrome, a true relationship may not be present.7–9 Basal cell carcinomas are increasingly conceptualized as adnexal in origin and thus it is not surprising that numerous adnexal elements are reported within this tumor.

Sebaceous carcinoma

Clinical features

Sebaceous carcinoma is rare and has traditionally been divided into two groups: an aggressive periocular variant comprising about 75% of cases and an extraocular form considered by some to be less aggressive.1–5 More recent observations, however, indicate that this distinction is inappropriate, since a significant number of extraocular tumors are associated with metastases and appreciable mortality.6–10 Indeed, a recent retrospective review of 1349 sebaceous carcinoma cases followed over a 31-year period from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database of the National Cancer Institute indicated no difference in overall survival between groups with periocular and nonocular sebaceous carcinoma.11

Periocular sebaceous carcinoma

The periocular variant is more common than the cutaneous or extraocular form and presents in the mid sixties.12 It arises in association with the ocular sebaceous glands. At least five types of sebaceous adnexae are recognized in the eye. The meibomian glands (tarsal glands) are modified sebaceous glands that are associated with the tarsal plates of both the upper and lower eyelids.13 They are relatively large structures that are not associated with hair follicles and which discharge through squamous epithelium-lined ductules into a larger central duct that ultimately empties at the margin of the eyelid. These glands contribute to the lipid content of tears.13 The glands of Zeis are associated with the eyelashes at the lid margin. Also recognized are the sebaceous glands of the caruncle, eyebrows, and those of the tiny vellus hairs on the surface of the eyelid.9

Sebaceous carcinoma is the second or third most common malignant tumor of the eyelid after basal cell carcinoma (and probably squamous cell carcinoma), accounting for 1.5% to more than 25% of tumors in several large series from referral centers.9,14–19 It is a significantly more common diagnosis in series from Asia, but it is not clear that Asian populations in the USA have a higher incidence. The difference may well be due to a relatively low incidence of other malignant tumors such as basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma in this population.9,11,20 Most series from other regions place the incidence at approximately 1–5% of malignancies of the eyelid.9,12

Tumors generally arise in association with the meibomian gland, and present as a steadily enlarging, nonulcerated mass that usually involves the upper eyelid.21 Occasionally, tumors develop from the glands of Zeis and from the sebaceous glands of the eyelid, caruncle, and eyebrow.1 Sometimes they are multicentric or diffuse.22–24 Occasionally they present in younger patients.23 There was believed to be a slight female preponderance, but this is not clear in the largest studies to date.11,21,25

The tumor is very rarely diagnosed clinically, as presentation is notoriously varied. Many lesions are mistaken for basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and even as a chalazion or chronic blepharoconjunctivitis.21,26 The metastasis rate with subsequent mortality is high, approaching 25%.11,21 Aggressive local behavior with intracranial extension may also occur.27 The metastatic and mortality rate can be significantly lowered (to 18%) with early detection and treatment.28,29 The organs most often affected include the regional nodes with subsequent involvement of lung, liver, brain, and bone.9 Metastatic disease is a poor prognostic sign with a 50% 5-year mortality in one study.21 Prognosis is particularly poor when both the upper and lower eyelids are involved.21 Sentinel lymph node biopsy may be helpful for disease staging.30

Sebaceous carcinoma has been documented in retinoblastoma patients treated with radiotherapy, although it has also been reported in these patients in the absence of such treatment and occurring in a considerably younger age range.31–33 Tumors associated with HIV infection have also been reported.34

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree