KEY TERMS

Consumer-directed health plans

Health maintenance organization (HMO)

Preferred provider organizations (PPOs)

It was obvious almost as soon as Medicare and Medicaid were enacted that the U.S. healthcare system still had problems. Medical costs in the United States, which had been rising more rapidly than general inflation, rose even more rapidly, putting a strain on all forms of health insurance. Access to medical care was difficult for many Americans because they lacked insurance. And despite the high costs, there were indications that the quality of medical care might not be as high as Americans liked to believe. A variety of attempts have been made to reform the system, aimed at controlling costs and improving access, none with significant success until the most recent attempt, described later in this chapter, President Obama’s 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA), which took full effect in 2014.

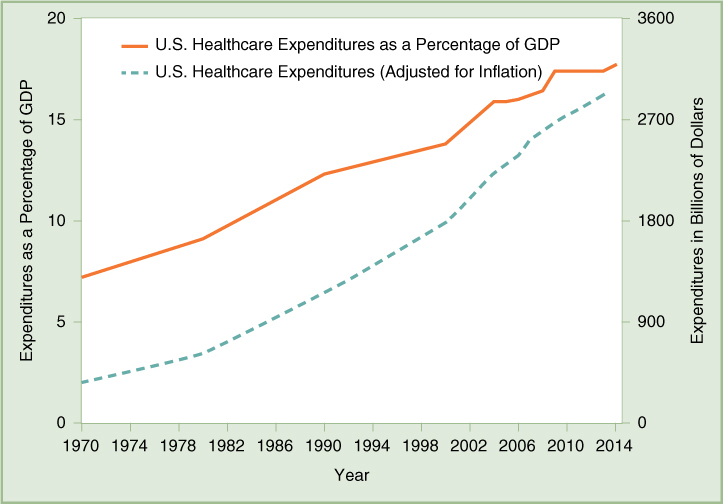

(FIGURE 27-1) shows the growth in medical care expenditures in the United States since 1960. In that year, approximately $27 billion was spent on medical care. In 1970, the figure had grown to $74 billion. By 2014, national health expenditures had reached $3.08 trillion dollars per year.1 The rate of increase has consistently been faster than the overall growth rate of the economy, leading medical costs to have constituted a larger and larger percentage of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP). In 1960, medical expenditures were about 5 percent of the GDP; in 2014, they were 17.7 percent.1

FIGURE 27-1 U.S. Healthcare Expenditures Between 1970 and 2014

Data from Health Affairs 28(1) (2009): 246–261, and Health Affairs 34(1) (2015): 1–11. Inflation is adjusted using GDP price index based on author calculations.

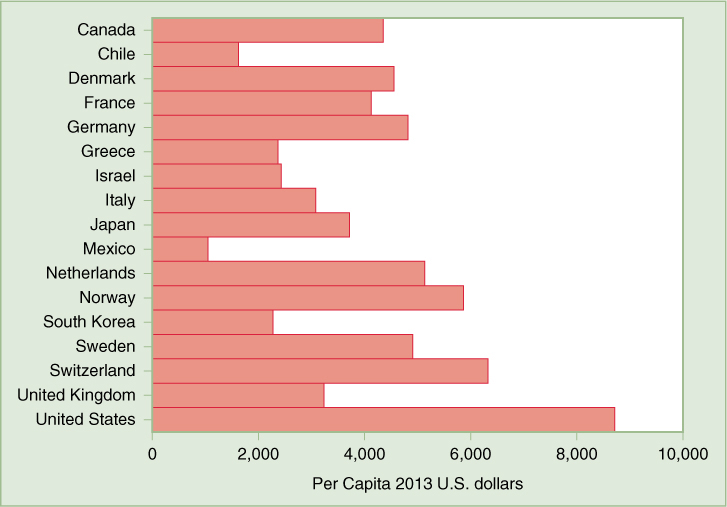

Although expenditures on health have risen all over the world, the United States spends far more on medical care per person than any other country in the world. In 2013, an average of $8,713 was spent on health costs for each American, more than twice the average of a group of 29 industrialized countries that are members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (see FIGURE 27-2).2 Spending as a percentage of GDP is also higher in the United States, amounting to 16.4 percent in 2013; the Netherlands and Switzerland followed at 11.1 percent; and the average for the 29 OECD countries for which data was available was 8.8.percent.

There is no evidence that Americans are healthier as a result of the greater expenditures. As measured by the common indicators of health status used for international comparisons, the United States does poorly. Of OECD countries compared in 2011, the United States ranked 27th out of 30 in infant mortality; its life expectancy at birth was 26th for males and 27th for females out of 34 countries. Our life expectancy at age 65, ranked 20th for males and 25th for females.3

Problems with Access

Despite the large expenditures, many Americans have difficulty getting access to medical care when they need it. About 41.8 million people, or 13.3 percent of the population, lacked health insurance for the entire year in 2013.4 Many more may be uninsured for part of the year. The numbers were increasing and were predicted to continue to rise before ACA was implemented. In 2010, the year ACA was passed, 15.5 percent of the population lacked health insurance. Most of the uninsured are poor, and the percentage of uninsured citizens decreases as their income increases. The percentage of children who are uninsured has declined to less than 10 percent because of the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) passed in the 1990s. But young adults are the group most likely to be uninsured: 22.6 percent of those ages 19 to 24 and 23.5 percent of those ages 25 to 34. Members of racial and ethnic minority groups are more likely to be uninsured than white Americans: About 15.9 percent of blacks and 24.3 percent of Hispanics were uninsured in 2013, compared with 9.8 percent of non-Hispanic whites.4 Before the ACA, many of the uninsured were patients with chronic diseases who were closed out of the market because of policies that denied coverage for preexisting conditions. That practice is prohibited by the ACA.

FIGURE 27-2 Per Capita Health Spending in Selected OECD Countries, 2013

Data from OECD. Stat, Health Expenditure and Financing table, stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?DataSetCode=HEALTH_STAT#, accessed September 27, 2015.

The problem of access to medical care is closely related to the problem of its cost. As monthly premiums have risen in proportion to wages, it has become increasingly expensive for employers, especially small businesses, to provide health insurance for employees and their families. Employers have cut back on their coverage, shifting more of the costs to the employees by requiring them to pay a larger share of the premiums, higher deductibles, and higher copayments. Some low-wage workers may choose to remain uninsured because their share of the premiums is too high; yet these workers earn too much to qualify for Medicaid in most states. In 2014, more than 80 percent of the uninsured lived in families headed by workers. Uninsured workers are mostly employed in the agricultural industry, in service-sector jobs, or work part-time.5

No other industrialized country has such large numbers of uninsured citizens as the United States. The western European countries, Japan, and Canada have national health plans that virtually guarantee coverage to all citizens. They spend less per capita and devote a smaller percentage of their economies to medical costs.

Lack of insurance clearly leads to poorer outcomes when people are sick. People who are uninsured tend to postpone seeking medical care when they need it, and they may be denied care. If they are sufficiently sick, they may go to an emergency room, which is required by law to treat them, and the cost of their care may be borne by shifting it to other payers, increasing the charges for insured patients. This is not, however, the most effective form of medical care. The uninsured are more likely to be hospitalized for preventable illnesses than insured patients, and they are less likely to survive a serious illness.6 A study published in 2009 found that people without health insurance had a 40 percent higher risk of death than those with private insurance, leading to 45,000 deaths each year.7

Although Medicare has ensured that most of the elderly have access to medical care when they need it, escalating costs have had an impact here, too. Each year the program pays out more than it collects in premiums, and Congress has repeatedly tried to make adjustments to save the system from bankruptcy. In 2014, 14 percent of the federal budget went to Medicare, and spending is growing, although more slowly since the passage of the ACA.8 Attempts to cut costs are politically delicate because the elderly are fiercely protective of their entitlements. Because of the overall growth of medical expenses generally, together with requirements for beneficiaries to pay deductibles and copayments, the elderly now pay on average 14 percent of their income out-of-pocket for medical care. Most have some form of supplemental insurance plan.9

Medicaid, a joint federal-state program, has never worked as well as it was expected to, but after passage of the ACA, it covers many more poor Americans. The ACA as originally written expanded Medicaid to cover all low-income adults, but a Supreme Court decision allowed states to opt out of the expansion. Twenty-eight states implemented the expansion, and in these states even childless adults below a median of 138 percent of the federal poverty level are eligible for Medicaid. In states that decided not to participate, childless adults are not covered. All but two states cover children at or above 200 percent of the poverty level with either Medicaid or CHIP. In 33 states, pregnant women at or above 200 percent of the poverty level are eligible for Medicaid.10

In some states, the fixed fees that the program pays to providers are so low that doctors are unwilling to participate in the program, making it difficult for families that have coverage to find someone to treat them other than poor-quality “Medicaid mills.” Even so, the growing costs of Medicaid are placing a strain on many state budgets, using funds that might otherwise be used for education or other services. Although almost 85 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries are children, their parents, and pregnant women, 25 percent of the spending goes to long-term care for the elderly and disabled.11,12

Overall, although the American medical system is the most expensive in the world, it is highly inefficient. The United States spends a higher proportion of its resources on health care than other countries; at the same time a significant proportion of the population is denied services, a situation almost unheard of in other countries. Moreover, the health status of the American population is poor in international comparisons—evidence that all the spending on medical care cannot compensate for failures in the public health system.

Why Do Costs Keep Rising?

A number of factors are responsible for the high and rising cost of medical care in the United States, some of them common to all industrialized countries, some unique to the American system. The aging of the population, for example, is a problem common to most countries. Because older people generally have a greater need for medical care, aging populations are driving up medical expenditures everywhere. In fact, several other countries have older populations than the United States.

Another factor that increases costs everywhere is the continual development of new medical technology and high-tech procedures. New instruments such as computed tomography (CT) scanners and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) devices and new procedures such as arthroscopic and laparoscopic surgery and cardiac catheterization are expensive. They can be very effective in diagnosing and treating illness, so they are used widely—perhaps too widely. However, these technologies are available in all advanced countries, and it is not clear that they are more widely used in the United States.13

When inflationary factors that are unique to the American system are considered, administrative costs are one of the favorite targets of blame. According to one estimate published in 2003 but not thought to have changed significantly, 31 percent of the American medical budget is spent on administration. Twenty-seven percent of medical workers in the United States spend most of their time on paperwork, up from 18 percent in 1968.14 Because many different insurers pay for medical care, each with its own forms and documentation requirements, the process of billing and paying for care in the United States is much more time consuming and expensive than in countries where the government pays for everything. Moreover, some insurance companies, in trying to control costs, institute additional administrative procedures, for example, requiring doctors to justify the need for certain treatments. This has the paradoxical effect of increasing paperwork and the percentage of effort and expense that goes to administration. As one eminent health economist lamented: “I look at the U.S. healthcare system and see an administrative monstrosity, a truly bizarre mélange of thousands of payers with payment systems that differ for no socially beneficial reason.”15

Another peculiarly American characteristic that adds to medical costs is our tendency to sue for malpractice when something goes wrong. Doctors complain about the exorbitant price of malpractice insurance, and occasional news stories tell of a multimillion-dollar jury award to an unfortunate patient who was harmed by some medical procedure. Although these costs do not in themselves have a significant overall impact, the fear of malpractice suits may affect a physician’s decisions. Doctors may practice “defensive medicine,” ordering more diagnostic tests and medical procedures than necessary, to document in court that they did “everything possible” for the patient.

In fact, studies have shown that the whole system of malpractice compensation is inefficient and unjust. Most patients who are harmed by poor medical treatment are not compensated, and many patients who have suffered a bad outcome sue and win, even when the medical provider was not negligent.16 However, because many Americans still lack health insurance, winning a malpractice suit may be the only way an injured patient will be able to pay for treatment of his injury.

One analysis of why medical spending in this country is higher than in other OECD countries found that the United States has higher rates of chronic diseases associated with obesity, including diabetes and heart disease. Almost two-thirds of Americans are overweight or obese, far outnumbering the prevalence in other countries, where, on average, 47 percent of the population has a BMI greater than 25.13

Among the most significant factors driving up medical costs are financial incentives for medical providers. In the “fee-for-service” system of payment, doctors and hospitals are motivated to provide more services in order to increase their income. Moreover, the performance of surgical procedures and the use of high-tech diagnostic equipment are more profitable than the more time-consuming practices of talking, listening, observing, and touching. Along with the growth of new medical technologies has come the growth of specialization among physicians. Fewer than 50 percent of doctors in the United States work in primary care, which includes family practice, general internal medicine, pediatrics, and obstetrics/gynecology. The majority of American physicians practice the more lucrative technological specialties such as radiology, anesthesiology, ophthalmology, cardiology, gastroenterology, and urology. Because of the relatively low pay for primary care providers, many patients looking for an internist or pediatrician may not be able to find one.17 There is concern that the new healthcare law will exacerbate the problem.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree