and Alena Skalova2

(1)

Departamento de Ciências Biomédicas e Medicina, Universidade do Algarve, Faro, Portugal

(2)

Department of Pathology, Medical Faculty Charles University, Plzen, Czech Republic

5.1 Definition, Site and Incidence

Warthin tumour (adenolymphoma, cystadenolymphoma, papillary cystadenoma lymphomatosum) is a benign well-encapsulated lesion usually occurring in the caudal pole of the parotid gland. It consists of an oncocytic epithelial cell component arranged in double layers which develops cysts and papillary projections, and a variable stroma component with lymphoid tissue. The pathogenesis is still unknown but the most favoured hypothesis suggests that Warthin tumour (WT) results from proliferation of ductal cells that have been entrapped in parotid lymph nodes during embryonal life. During the late embryogenesis, the parotid gland becomes encapsulated to include adjacent lymphatic tissue within the gland. Ducts, but also acini in children, are therefore frequent findings in the normal intraparotid lymph nodes. Such a process does not occur in any other major, or minor, salivary glands. Warthin tumour is almost exclusively located in the parotid salivary tissue or in intra- and periparotid lymph nodes hence supporting such a theory. The epithelial structures of WT stem from both intercalated duct cells and ductal basal cells and the existence of these heterotopic ducts would also explain the high tendency for the neoplasm to be multifocal and bilateral. The most common site of WT, i.e. the tail of the parotid, is also the part of the gland that has the most intraparotid lymph nodes, would possibly further support origin from ectopic salivary tissue in the lymph nodes. Also immunohistochemical studies demonstrating D2-40-positive (podoplanin) sinus-like vessels at the inner layer of the capsule of WT support an origin in the lymph nodes. Mucoepidermoid and acinic cell carcinoma are other salivary gland neoplasms that on rare occasions may be encountered within a parotid lymph node, but these tumours (if not metastatic) are best considered as hamarblastomas. Not only the site of origin is unclear (lymph node or not) but also whether the proliferating, mitochondria-rich ductal oncocytic cells are true neoplastic or hyperplastic in nature. The rare occurrence of malignant transformation (see below) would possibly also support the view that this lesion should possibly better be classified in the group of hyperplastic, reactive tumour-like lesions rather than as a neoplastic adenoma [16, 17, 48, 86, 99, 105, 106]. Clonal analysis of the epithelial component in Warthin tumour has showed a polyclonal proliferation [51] and also the B- and T-cell components of Warthin tumour are polyclonal with oligoclonal expansion of both T and B cells [103]. A study using immunohistochemistry of CD3, CD20, kappa and lambda light chains, and PCR of IgH gene rearrangement, strongly suggests that the lymphoid stroma of Warthin tumour is reactive [100]. There are also suggestions that WT originates on the basis of an immune reaction of delayed sensitivity type [5, 39]. Simultaneous occurrence of IgG4-related disease and WT has recently been reported, which also raises the suspicion that an immune reaction is involved in the pathogenesis of WT [1, 2, 59]. Somewhat on the same line, but based on studies of cell adhesion molecules, there are suggestions that the bilayered excretory ductal structures are the result of a hyperplastic process of the glandular epithelium that interacts with the excessive lymphoid tissue of the stroma [6]. Further, there are very few, if any, reports in the literature describing dysplastic changes of the oncocytic epithelium in Warthin tumours. There are hence arguments against that WT is a true neoplasia and WT is perhaps better regarded as reactive oncocytic metaplasia and hyperplasia induced and/or accompanied by an (immunologic) inflammation. Epstein-Barr virus does not seem to be involved in the pathogenesis of Warthin tumour [114], neither human papilloma virus [107]. There used to be a strong male predilection with a male to female ratio of 10:1, whilst many of more recent studies show an almost equal sex distribution [55, 70, 95]. A Spanish study contrasts however with a striking male predilection in a series of 62 males and one female patient with WT [3]. A very large Chinese retrospective study from 2010 (6,982 salivary gland tumours) reported the male predominance of 92 % for WT [109]. The rather strong association between WT and smoking has been known for a long time, and the increasing number of female smokers during the last decades may perhaps account for the apparent change in sex incidence [14, 18, 20, 31, 40, 58, 79].

After pleomorphic adenoma, WT is the most common tumour of the salivary glands. Warthin tumour was first reported by Hildebrand in 1895 and later described by Albrecht and Arzt in 1910 as a separate diagnostic entity which they called papillary ‘cystadenoma in lymphatic glands’ [4, 49]. In 1929, Warthin described the cases of this disease known up to then and the tumour later became known as Warthin tumour [111]. Although rather low incidence figures such as 5.3 % of parotid tumours have been reported [28], another American study reported Warthin tumours represent over 20 % of parotid tumours [94]. It is clearly the second most common benign salivary gland tumour and in a series of 239 benign parotid tumours, 55.2 % were pleomorphic adenomas, whilst WTs constituted 36.4 % of the tumours [15]. Similarly, the ratio of Warthin tumour to pleomorphic adenoma was 1:1.9 in a series of benign parotid tumours in an Asian population [18]. There are also indications that over the last decades, there is a decrease in the relative frequency of pleomorphic adenoma but an increase in WT [29]. Warthin tumours are by far the easiest salivary neoplasm to diagnose microscopically, and few, if any, are sent for a second opinion. One could hence argue that some series reported from referral centres or regional/national institutes might be biased towards diagnostically difficult salivary tumours and a false low incidence of Warthin tumours could arise. A recent general study on the incidence of salivary gland neoplasms in a defined UK population was performed, and thus patients referred from outside the catchment area were excluded. Their data suggested 70–75 benign and 8–14 malignant salivary neoplasms present annually/million population [13]. There also appear to be regional, national and racial differences and correct estimation of true incidence of WT is indeed difficult to make (See also Chap. 7). A reasonable estimate would likely be that Warthin tumours constitute as much as 15–25 % of all parotid tumours [31, 32, 80–82, 112].

Warthin tumour is almost exclusively a parotid lesion with the vast majority arising in the superficial portion. Many appear to arise in intra- and periparotid lymph nodes. Most cases of extraparotid WTs have been reported as case reports, and there are only few series available [8, 34, 83, 110]. In two series of 333 and 176 cases of Warthin tumours, 9 (2.7 %) and 14 (8 %) of the cases were extraglandular tumours, respectively [27, 98]. The majority of other reports of extraglandular Warthin tumours also concern lesions in extraglandular or neck lymph nodes, and there are exceedingly few cases reported elsewhere but for a few in the submandibular gland, palate, buccal mucosa, lips, larynx and nasopharynx [24, 39, 53, 54, 57, 75, 77, 110].

Multiple tumours of the salivary glands are in general rare and occur as tumours with identical histology, or with different histology. They can be unilateral or bilateral, synchronous or metachronous. The most common multiple salivary gland tumours with identical histology are WT followed by pleomorphic adenoma [30, 91]. Multiple salivary glands should be distinguished from tumours with biphasic differentiation and from hybrid tumours (see Chap. 15). Synchronous benign and malignant salivary gland tumours are very rare and less than a dozen cases have been described in the English literature, and Warthin tumour and mucoepidermoid carcinoma are the most common [19]. Multiple Warthin tumours, and synchronous multiple parotid tumours including one or two Warthin tumours, are possibly more common than previously recognised. Warthin tumour is estimated to be bilateral in at least 7–10 % of cases and multifocal in 2 % of cases [7, 22, 47, 50]. In one series of 78 Warthin tumours, multiple tumours were detected inasmuch as 20 % of cases, and a third of these cases were also bilateral [65]. Bilateral Warthin tumours were found in 10 % of cases in a study of 73 patients [18]. In another study of 341 patients with parotid tumours, synchronous multiple tumours were found in 14 cases. In nine of these 14 cases, there were two to four Warthin tumours, and one case of WT and a pleomorphic adenoma, and one case of Warthin tumour synchronous with a MALT lymphoma [117]. Bilateral intraparotid and extraparotid Warthin tumours in the same patient are also described [93]. These findings emphasise the need in all cases of Warthin tumour to examine the entire parotidectomy specimen for other lesions. There are also reports of parotid Warthin tumours synchronous with laryngeal and nasopharyngeal Warthin tumours [63, 76]. A case of possible familiar Warthin tumour with occurrence in monozygotic twins has been reported [42].

5.2 Clinical Features and Gross Appearances

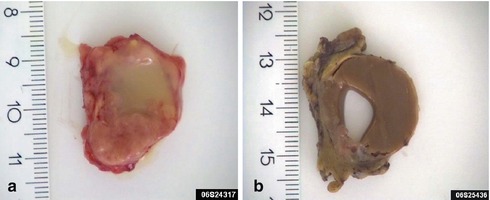

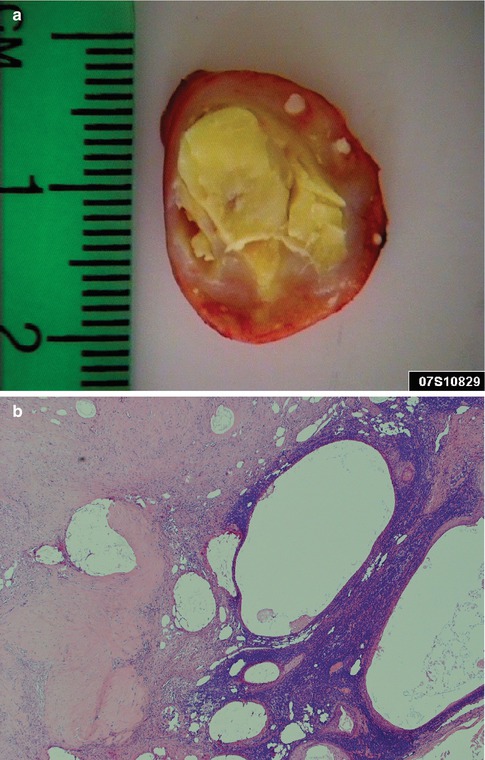

Warthin tumour usually presents as a painless, slowly growing, often egg-shaped swelling in the parotid gland. It tends to be mobile and is usually less than 5 cm in diameter although tumours larger than 10 cm have been described [113]. It is most commonly located in the posterior and inferior parts of the parotid gland. The average time of awareness of the swelling at diagnosis is 1–2 years [32]. Pain is rarely present, but many patients notice fluctuation in size of the swelling, especially when eating. On exceedingly rare occasions, ulcerating Warthin tumours have been described. The ulceration of the overlying epidermis is thought to have resulted from inflammatory changes or postoperative fistula in recurrent WT [26, 85, 102]. Warthin tumour is typically a round or oval mass covered by a thin capsule. The cut surface varies considerably and may be firm, solid and white. Most commonly, however, there are one or more cystic spaces. The cysts are filled with clear, serous or brownish fluid, or even sometimes cheesy material (Fig. 5.1).

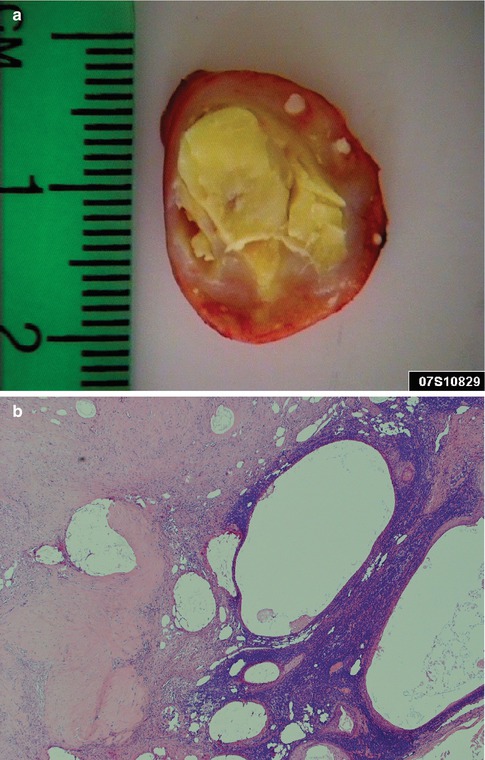

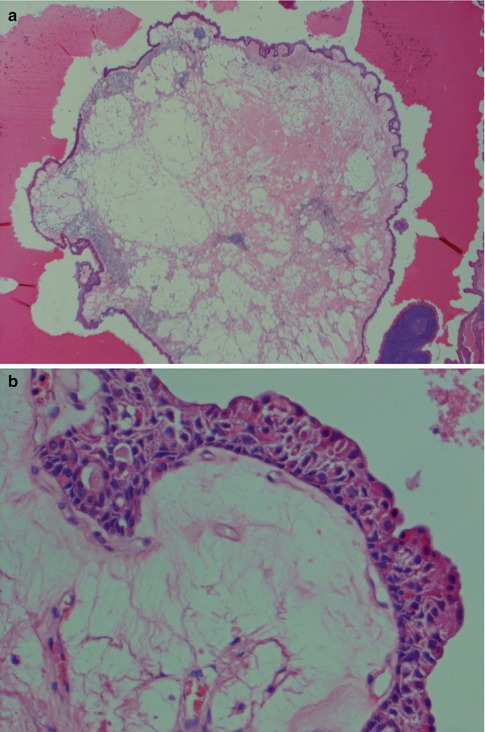

Fig. 5.1

(a) Cystic WT with serous fluid, partly cheesy material. (b) WT with a large cyst containing a brownish, almost chocolate-like, thick fluid

5.3 Histopathology

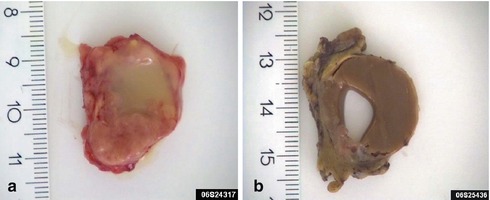

Warthin tumour is surrounded by a capsule that may be incomplete. In most cases, the capsule is thin (<200 μm) and in fact in many cases less than 100 μm [112]. The tumour is composed of strands of epithelial cells with frequent papillae in a background of variable amount of lymphoid tissue, often with germinal centres. The tumour is often multifocal (Fig. 5.2). The outer luminal layer of the strands comprises finely granular, oncocytic and rather tall columnar cells. These luminal cells often form small blebs resembling apocrine secretion and that can clearly be seen in all Warthin tumours. The inner cells are more cuboidal or flattened and with similar, but less abundant cytoplasm. These cells are more basal in type and most also stain positively for p63. Smaller foci of squamous as well as mucous metaplasia with goblet cells can be seen. On very rare occasions, sebaceous cells are present (Fig. 5.3). The presence of cilia on the oncocytic luminal cells is controversial. There are, however, a few studies performed on both light and electron microscopy level that support the presence of cilia on the luminal cells of Warthin tumours [25, 32, 52, 111]. There is a variable amount of cystic spaces and distended cysts may be associated with attenuation of the epithelium. The cysts are usually filled with an eosinophilic secretion or amorphous material; sometimes cholesterol clefts and accompanying inflammatory and multinucleated giant cells are present (Fig. 5.4). Concentrically laminated bodies resembling corpora amylacea may be present. On very rare occasions, sebaceous cells are present. The epithelial component of Warthin tumour reacts strongly with cytokeratins and particularly for cytokeratins typical for columnar differentiation, e.g. CK7 (Fig. 5.5). The lymphocytic infiltrate comprises approximately the same amount of T and B lymphocytes, but there are usually considerably more CD4 positive T lymphocytes than CD8-positive cells (Fig. 5.6). These findings may support the theory that Warthin tumour originates on the basis of an immune reaction of delayed sensitivity type. Further, and as discussed above, the B- and T-cell components are polyclonal with oligoclonal expansion of both T and B cells.

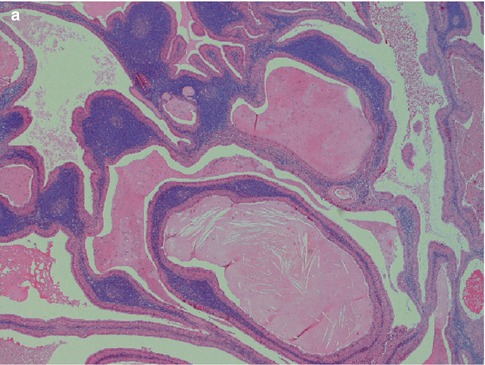

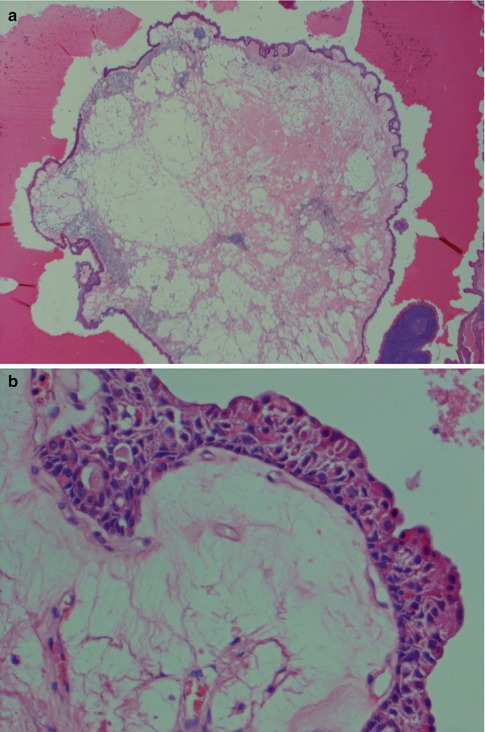

Fig. 5.2

(a) Typical appearance of WT with papillary epithelial projections in cystic spaces and lymphoid stroma. (b) WT with more solid growth pattern, less lymphoid stroma and only few smaller cysts. (c) Multifocal WT with the main tumour seen at top and a small nodule in the intraparotid lymph node

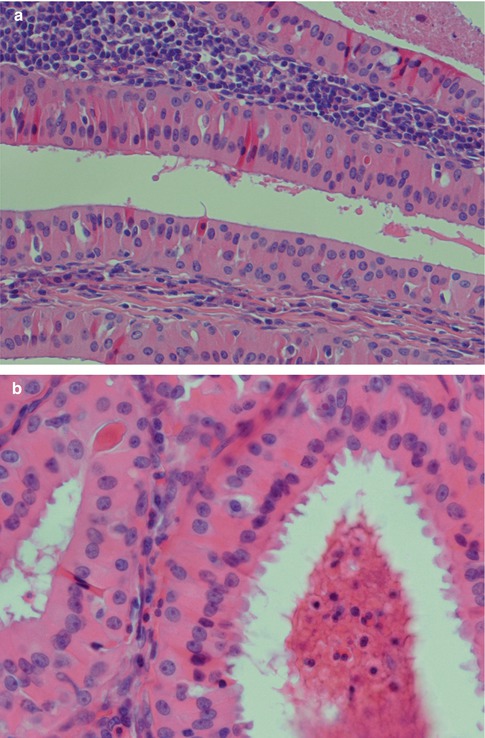

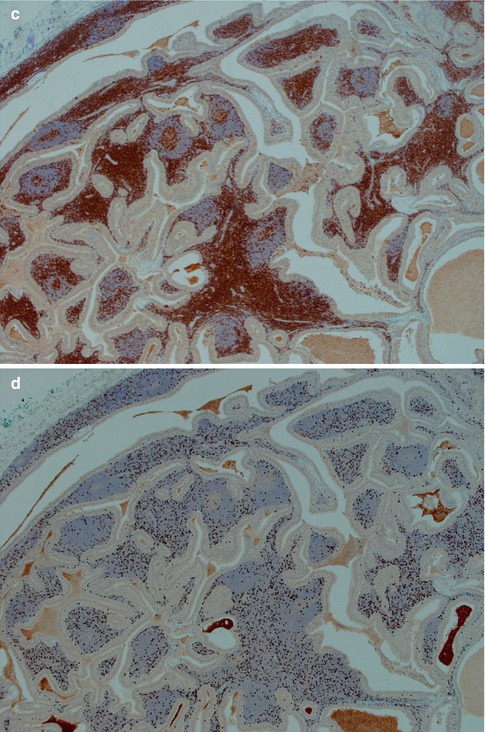

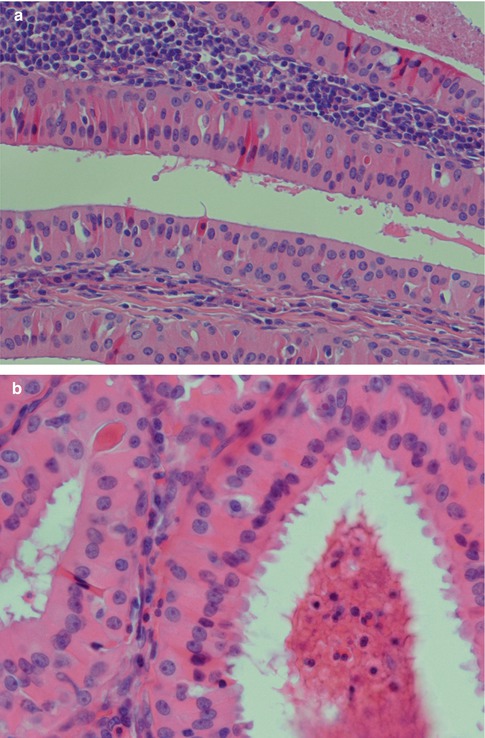

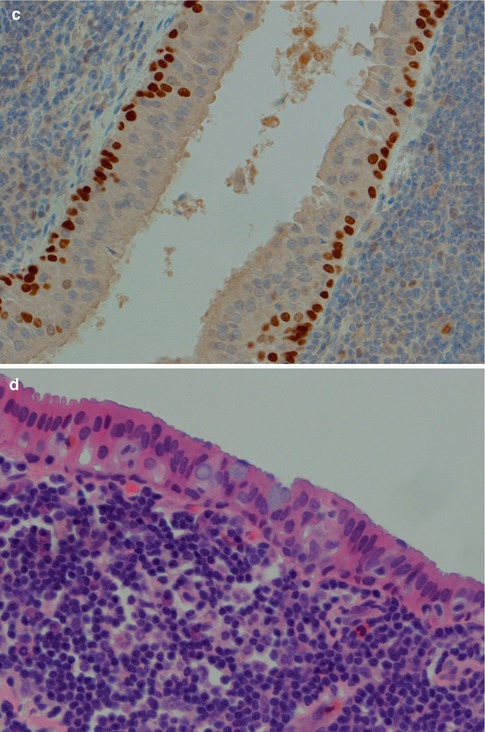

Fig. 5.3

(a) Typical bilayered oncocytic cells. (b) The tall luminal cells frequently have small blebs. (c) p63 staining of basal cells. (d) Mucous metaplasia with a few goblet cells

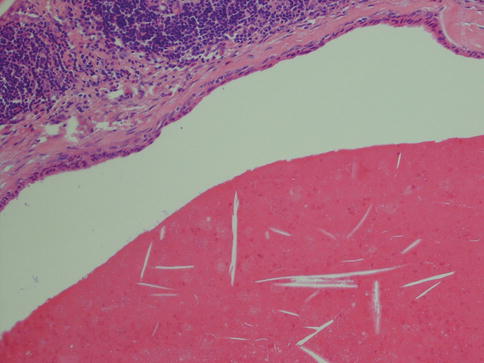

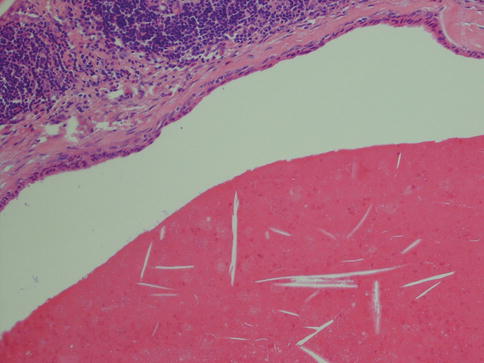

Fig. 5.4

Cyst filled with amorphous material with cholesterol clefts. The epithelium has lost its typical appearance and shows pronounced attenuation

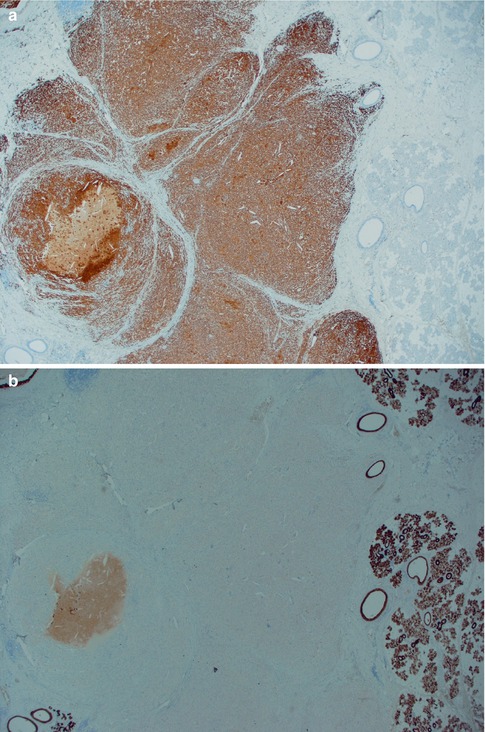

Fig. 5.5

WT immunostained with CK7

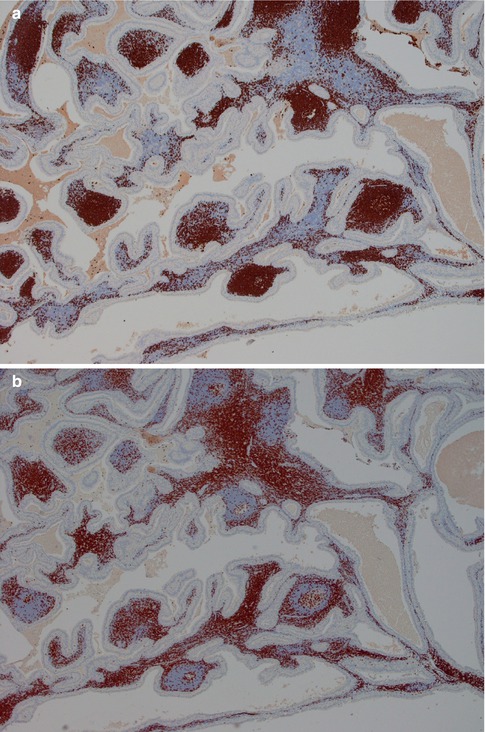

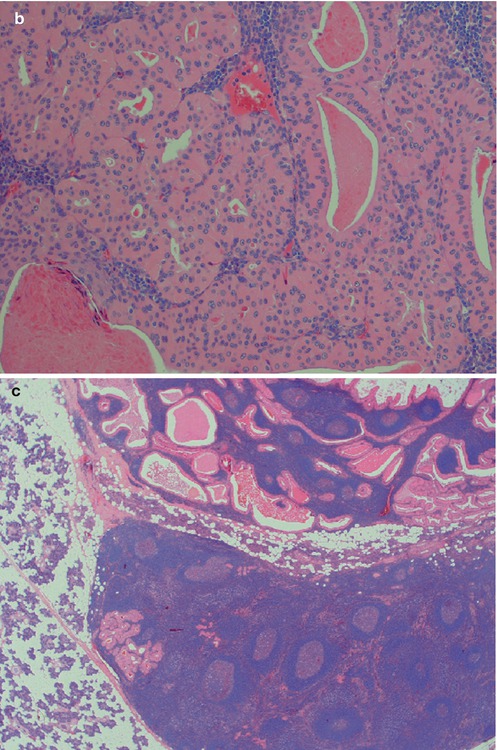

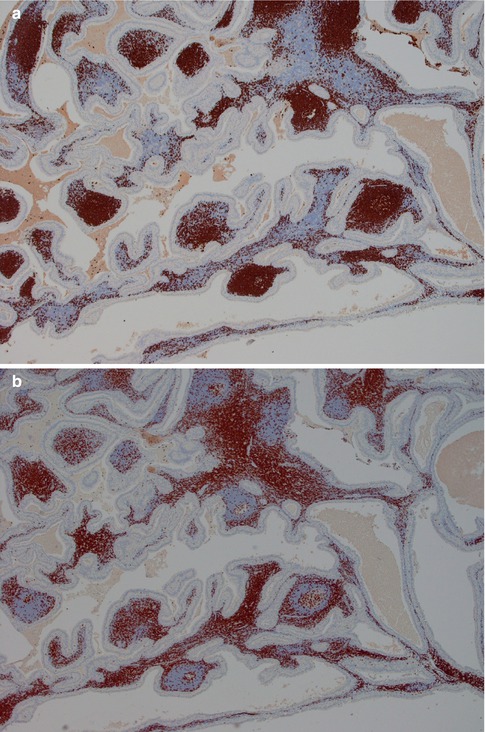

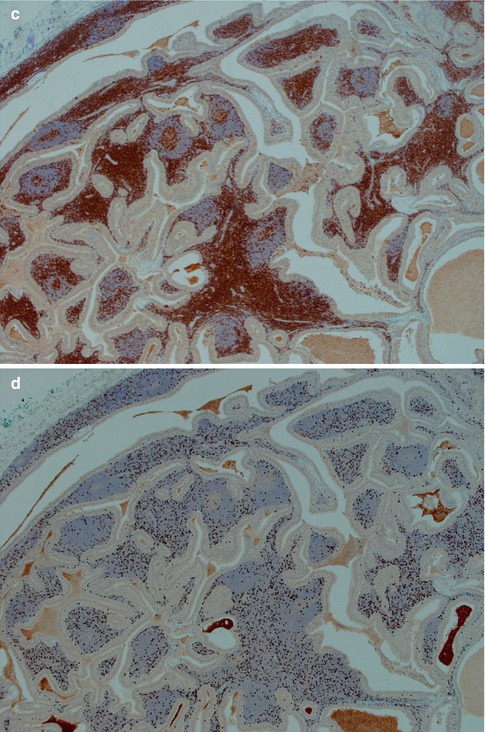

Fig. 5.6

(a) B lymphocytes in a WT stained with CD20. (b) Immunostain with CD3 – approximately the same amount of T as B lymphocytes. (c) CD4 stain. (d) CD8 stain – considerably less positive cells

A histological subclassification of Warthin tumours was suggested by Seifert and associates [92]. Depending on the ratio of epithelial tumour and lymphoid stroma, three subtypes were distinguished, as well as a fourth subtype that had large areas of squamous metaplasia and regressive changes. The most common type, subtype 1, has an epithelial component of 50 %. Subtype 2 is a ‘stroma-poor’ variant with the epithelial component being 70–80 % of the lesions. Subtype 3 is a ‘stroma-rich’ tumour with an epithelial component of only 20–30 %. In the study of 275 cases of Warthin tumours by Seifert and associates, subtype 1 represented 77 % of cases, subtype 2 13.5 %, subtype 3 only 2 % and subtype 4 represented 7.5 % [92]. Similar figures were found in a smaller study of 33 Warthin tumours, however, somewhat higher incidence of subtype 3, the stroma-rich variant [112]. The clinical relevance of this histological subclassification may be very limited, but the fourth subtype warrants some attention.

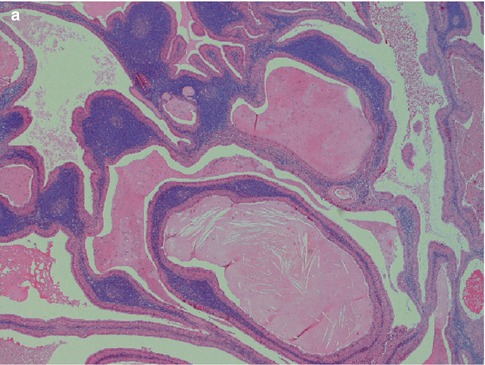

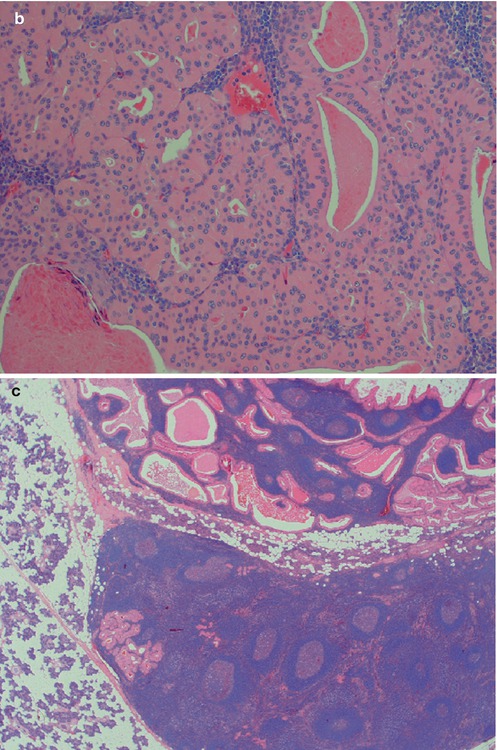

The fourth subtype with its squamous metaplasia of the epithelium and regressive changes in the stroma has variously been termed infected, infarcted and metaplastic Warthin tumour. The latter term is nowadays more widely accepted. Metaplastic Warthin tumour can be a serious diagnostic pitfall in routine histopathology with misinterpretation for malignancy, primarily mucoepidermoid carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma, but also for tuberculosis or sarcoidosis. In two large series of Warthin tumours (series of 323 and 275 cases), the authors found 6.2 and 7.5 %, respectively, to be metaplastic Warthin tumours [33, 92]. A considerably more recent study, but smaller (76 cases), reported infarction following fine-needle aspiration in 9 % of cases [104]. The metaplastic features are hence to be expected in approximately every 15th case of WT. Metaplastic Warthin tumours are widely recognised and their histological features have been described in detail [23, 33, 36, 89, 92, 101]. There have been some reports indicating that some cells in areas of squamous metaplasia in WT possibly had MAML2 rearrangement. However, a large recent study by Skalova and associates included 16 cases of metaplastic WT, but CRTC1-MAML2 and CRTC3-MAML2 fusions were not detected [97] (see also Chaps. 7 and 16). The morphology of a metaplastic Warthin can vary considerably from case to case, but they all show various degree of replacement of the original oncocytic epithelium by metaplastic squamous cells. The squamous component is usually as epidermoid cells, but well-differentiated squamous cells with keratin can be seen. Most often, however, the features are dominated by areas of necrosis, fibrosis and inflammatory changes, often with numerous histiocytes. The latter may sometimes mimic a granulomatous reaction and cases with multiple sarcoid-like granulomas have been described [84]. These inflammatory and reactive changes are often more predominant than the presence of metaplastic squamous cells (Fig. 5.7). The necrosis can be almost complete, leaving only scattered epithelial cells in a dense histiocytic reaction with cholesterol clefts, pigment deposits and multinucleated giant cells. In cases with extensive necrosis and inflammatory reaction, remnants of the epithelial component of Warthin can sometimes hardly be visualised unless using immunostainings with cytokeratin 7 (or other cytokeratins typical for columnar differentiation, i.e. cytokeratins 8, 18 and 19). Cytokeratins typical of squamous differentiation are usually negative (e.g. cytokeratins 10 and 13), but high molecular weight cytokeratins can be positive. Cytokeratin 14 is negative. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma can in some instances constitute a serious differential diagnosis to metaplastic Warthin. Unfortunately a mucicarmine stain is not a reliable discriminator as Warthin tumours, as well as metaplastic Warthin tumours, show scattered positivity for mucin, both intra- and extracellularly. The identification of columnar cells will help greatly in identifying a metaplastic Warthin (Fig. 5.8). Occasionally the cystic spaces in Warthin tumours contain islands of loose connective tissue that appears to be floating in the eosinophilic material. These structures are lined with a metaplastic epithelium, almost stratified epidermoid in type. The cores of the islands are oedematous and contain large amounts of foamy macrophages and some fibrous septa, blood vessels and smaller aggregates of lymphocytes. These islands are predominantly found in large, cystic Warthin tumours and likely represent degenerative changes and being a variant of a typical metaplastic Warthin tumour (Fig. 5.9).

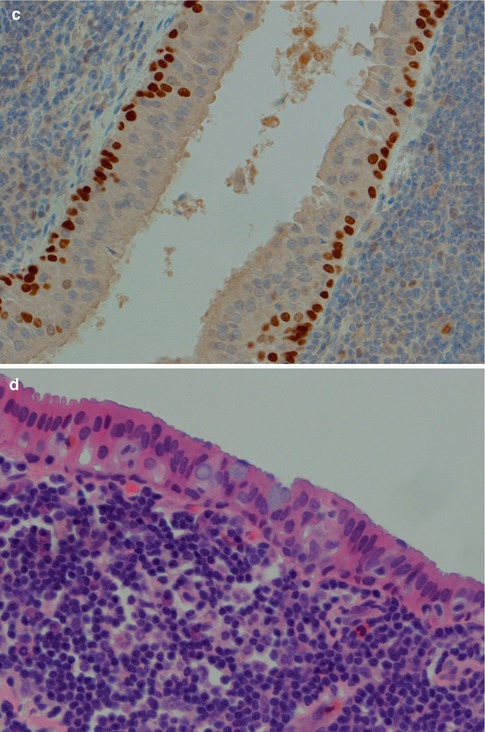

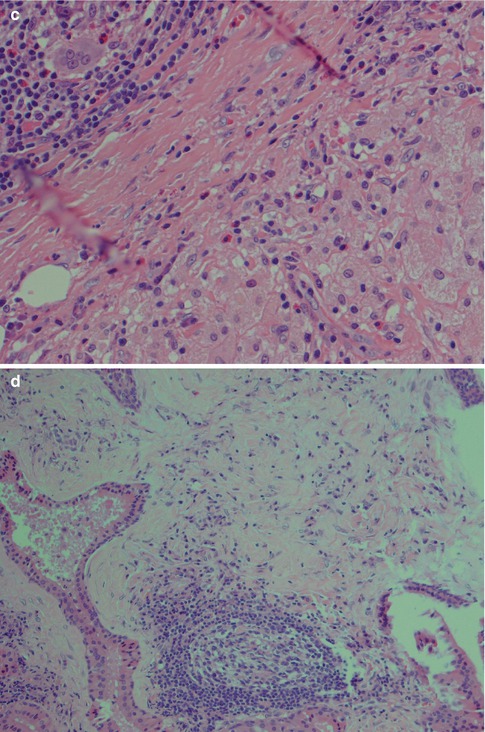

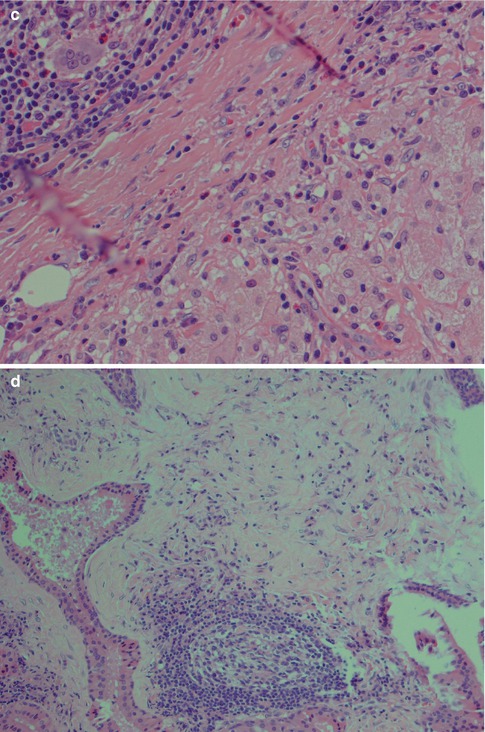

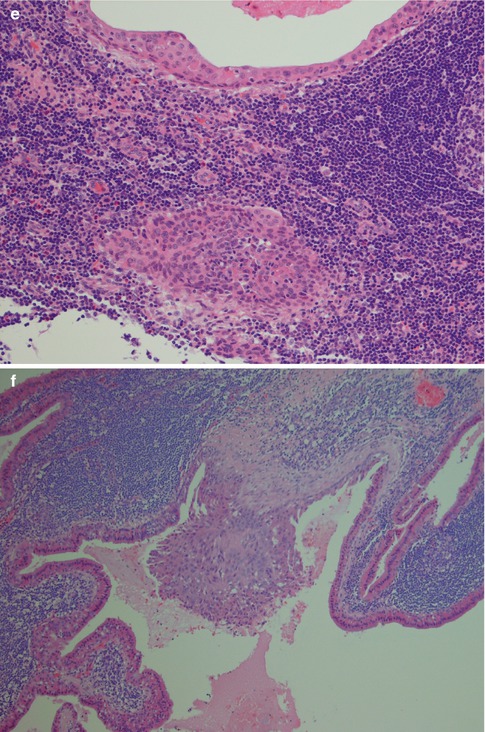

Fig. 5.7

(a) Metaplastic WT with cheesy material. (b) The same tumour with only remnants left of the oncocytic cells and lymphoid stroma. (c) Metaplastic WT with fibrosis, sheets of histiocytes and giant cells. (d) Another case with fibrosis in the centre. (e) The columnar cells of the cyst lining are partly replaced by epidermoid cells and there are also nests of epidermoid cells in the lymphoid stroma. (f) Another case of metaplastic WT with focal squamous metaplasia

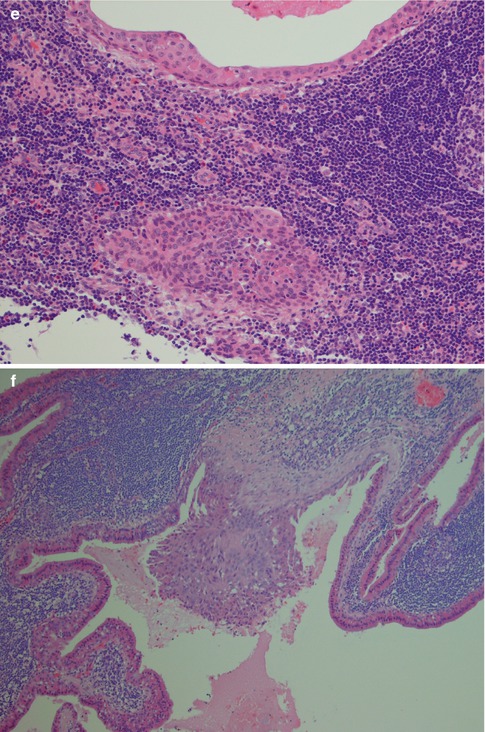

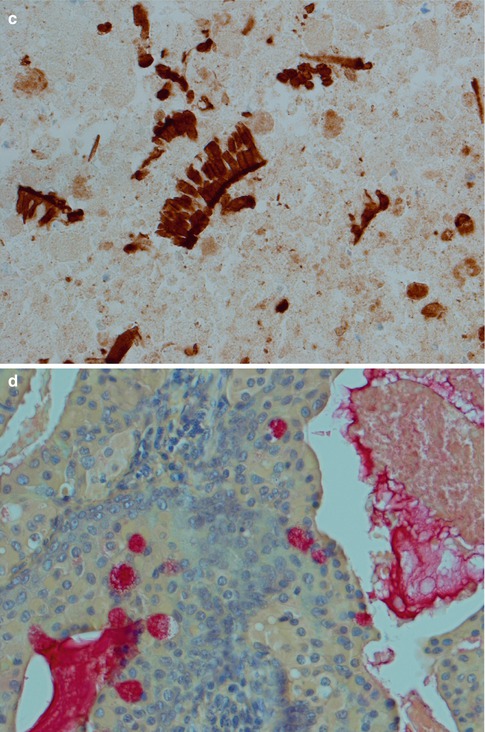

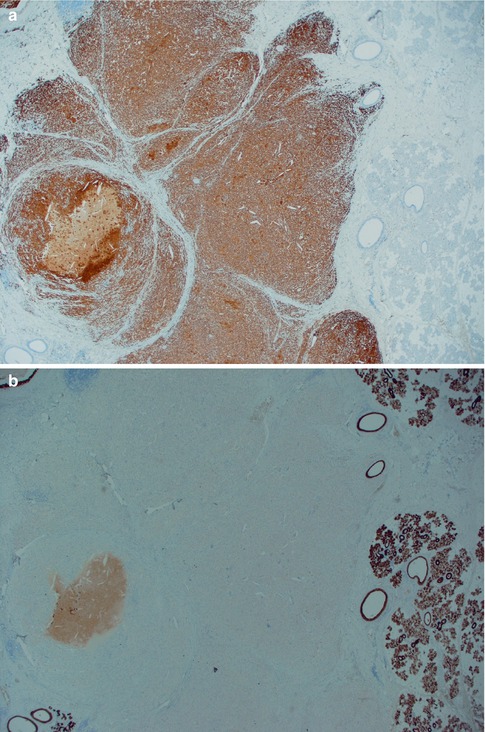

Fig. 5.8

(a) Metaplastic WT immunostained with CD68 showing histiocytic cells in the necrotic debris. Intact salivary gland tissue to the right. (b) Same area immunostained with CK7. No evident remnants of the epithelial component seen. (c) With higher magnification of the same area, small clusters of columnar cells are visualised by CK7 immunostain. (d) Mucicarmine stain of WT with intracellular as well luminal positivity

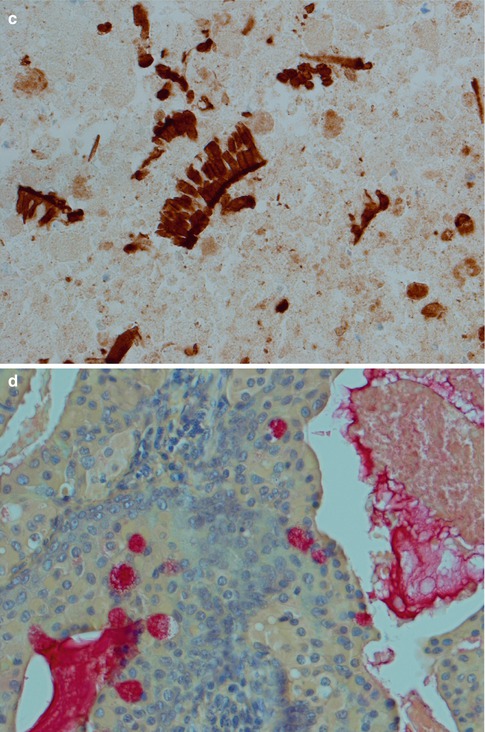

Fig. 5.9

(a) Variant of metaplastic WT with a ‘floating’ island of loose connective tissue and macrophages surrounded by an epithelium. (b) The typical double-layered oncocytic epithelium is replaced by an almost stratified, cuboidal/epidermoid type of epithelium

5.4 Genetics

As mentioned above there is a rather strong association between Warthin tumour and smoking. In an Asian population, smokers have reported to have a 40-fold greater risk than non-smokers of developing a Warthin tumour [18]. Smoking may induce damage to the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) due to the development of an increase in oxidative stress. Approximately 10 % of mtDNA bears the common 4,977 bp deletion and is present in the parotid salivary tissue in smokers as well as non-smokers. Although there is an age-related increase in the 4,977 bp deletion, the oncocytic cells of Warthin tumour show a significant increase in the level of this deletion [60, 61]. The translocation t(11;19)(q21;p13) described in mucoepidermoid carcinomas has been detected in a small subset of Warthin tumours. A study of 48 cases of Warthin tumours revealed the translocation and expression of the chimeric gene only in two cases. These two were metaplastic variants of Warthin tumours which are known to histologically overlap considerably with mucoepidermoid carcinoma [35]. CRTC1-MAML2 and CRTC3-MAML2 fusions were not detected in WT [97].

5.5 Malignancy in Warthin Tumour

Malignant transformation of Warthin tumours is very rare compared to the development of carcinomas in pre-existing pleomorphic adenomas. In the Salivary Gland Register of Hamburg 1965–1995, only five cases of malignancy were seen in a series of 900 Warthin tumours (0.5 %). Two were classified as mucoepidermoid carcinoma, and one each of oncocytic carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and acinic cell carcinoma [90]. Although there is one study reporting as much as 16 % of cases with Warthin tumours to be associated with malignancy [65], the very low incidence given from the Hamburg series appears to be more appropriate. A fair number of case reports of carcinoma associated with Warthin tumour can be found in the literature, and it appears as squamous cell carcinoma and oncocytic carcinoma are the most common. Carcinoma in Warthin tumour does, however, not necessarily imply malignant transformation of the epithelial oncocytic component. As mentioned above, synchronous benign and malignant salivary gland tumours are very rare but do exist, and Warthin tumour and mucoepidermoid carcinoma are the most common. It is therefore possible that some cases reported as malignant transformation may be examples of multiple tumours. Similar to the situation with malignancy associated with sinonasal inverted papillomas, where most carcinomas arise from neighbouring sinonasal mucosa and not the inverted papilloma itself, many carcinomas may be associated with Warthin and derived from neighbouring salivary gland structures. In 1997, Seifert described five malignancies arisen in Warthin tumours, but also reviewed cases available in the literature. The histological criterion for malignant transformation in a Warthin tumour includes the observation of a continuous transition zone from the benign double-layered oncocytic epithelium into an invasive epithelial malignancy. Based on Seifert’s report and subsequent published cases, the literature contains only approximately 45 such cases (12 cases of squamous cell carcinoma, 10 cases of oncocytic carcinoma, 8 mucoepidermoid carcinomas, 9 adenocarcinomas, 3 undifferentiated carcinomas, 1 salivary duct carcinoma and 1 acinic cell carcinoma) [11, 12, 21, 37, 38, 41, 46, 56, 64, 69, 71, 72, 88, 90, 96, 108, 115, 116].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree