Vascular Injuries to the Neck, Including the Subclavian Vessels

Benjamin W. Starnes

Nam T. Tran

Background

The neck is unique in that it contains multiple vital structures including respiratory, digestive, vascular, neurologic, and endocrine. In the severely injured trauma patient, all of these must be addressed and treated accordingly. While vascular injuries to the neck only account for 5% of all civilian vascular injuries, rapid management is critical once the airway has been secured to ensure patient survival and optimal outcome. Both penetrating and blunt mechanisms can cause injury to the vascular structures in the cervical region. Unlike other anatomic regions of the body, penetrating wounds comprise the majority of vascular injuries in the neck in urban trauma centers. While less common, blunt mechanisms can also result in significant injury to cervical vascular structures.

Historical Perspective

In 1552, the French surgeon Ambroise Pare ligated both carotid arteries and a jugular vein of a soldier injured in a duel. The soldier survived the operation, but unfortunately was left with hemiplegia and aphasia. Two centuries later, Fleming carried out ligation of a common carotid artery on a suicidal sailor with a successful outcome. The mortality associated with cervical vascular injuries in World War I was approximately 16% to 30% after both nonoperative management and ligation of actively hemorrhaging vessels. In World War II, a more aggressive policy toward routine exploration resulted in a significant decrease in mortality related to cervical vascular trauma. The first attempt at surgical repair of a cervical vascular structure, an injured carotid artery, was performed during the Korean War. Repairs at that time consisted of direct suture, primary anastomosis, and interposition vein graft. Modern-day management has included the addition of endovascular approaches with coil embolization of bleeding vessels and the placement of intravascular stents.

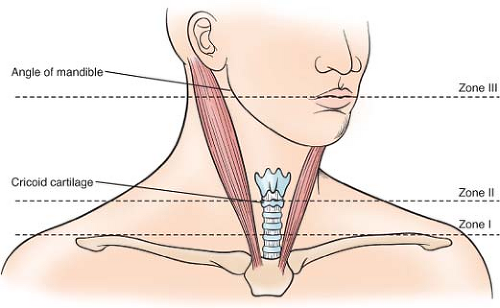

General Approach—Anatomic Zones

Classically, the management of cervical trauma is dictated by anatomic zones originally described by Monson at the Cook County Hospital in 1969 and still remain in use today (Fig. 1). Zone I is defined by the thoracic inlet inferiorly and the cricoid cartilage superiorly. In this area, structures at risk include the subclavian vessels, brachiocephalic vessels, aortic arch, and origin of the carotid arteries. Zone II is the midportion of the neck and is demarcated by the cricoid cartilage inferiorly and the angle of the mandible superiorly. This zone contains the carotid arteries, vertebral arteries, and the jugular veins. Lastly, zone III is the highest in the neck and is bound by the angle of the mandible inferiorly and the base of the skull. In this region, the carotid arteries and jugular veins are at greatest risk. Typically, injuries to structures in zone III are the most difficult to access surgically.

Etiology/Epidemiology

Overall, gunshot wounds account for the majority of cervical penetrating trauma.

Stab wounds often cause injury to the left neck due to the majority of the population being right handed. The common carotid artery is the arterial vessel most often injured followed by the internal and subsequently the external carotid artery. Mortality from penetrating missile wounds range anywhere between 2% and 10% and is dependent upon other associated injuries, time between injury to presentation, and the patient’s overall neurological status. In particular, those with profound neurological deficits carry the worst prognosis.

Stab wounds often cause injury to the left neck due to the majority of the population being right handed. The common carotid artery is the arterial vessel most often injured followed by the internal and subsequently the external carotid artery. Mortality from penetrating missile wounds range anywhere between 2% and 10% and is dependent upon other associated injuries, time between injury to presentation, and the patient’s overall neurological status. In particular, those with profound neurological deficits carry the worst prognosis.

Penetrating neck injury can be due to direct effect of the projectile resulting in partial or complete vessel transection. Localized effect, such as blast injury, can result in the formation of an intimal flap, dissection, pseudoaneurysm, or arteriovenous (AV) fistula. In 25% to 40% of cases, penetrating trauma results in vessel thrombosis. Of the vascular structures in the neck, the internal jugular vein (95%) and carotid artery (7%) are most often injured.

While penetrating neck trauma is often discussed and written about, the majority of injuries to the neck are caused by blunt force trauma. This can be the result of motor vehicle collision or due to sports-related injury (i.e., clothesline tackle), chiropractic manipulation, blow from the fists or feet, and strangulation.

Management—Operating Room Setup/Hybrid Setup

In the past, cervical vascular injury was treated via open surgical approach once the injury was identified. Often, this involved diagnostic imaging in a separate hospital location such as that of a computed tomographic (CT) scanner or the angiographic suite. This paradigm is suboptimal and often prolonged the time to surgical intervention in critically ill patients.

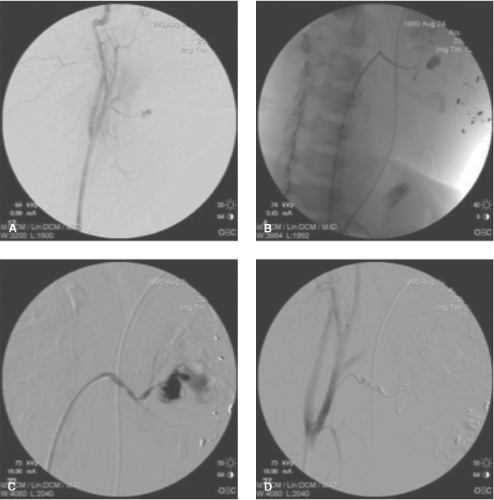

With the adoption of endovascular techniques, modern vascular surgeons are able to provide a full range of services to the patient with cervical vascular trauma from diagnosis to surgical intervention. Furthermore, the rapid expansion of novel endovascular approaches has allowed some injuries to be treated in a “minimally invasive” manner and avoid the morbidity of a full open exposure and repair (Fig. 2).

The modern operating room (OR) needs to be able to function as both an open operating theater and an angiographic suite. Such a theater needs to be able to allow one to perform a full range of open vascular reconstructions from simple vascular repair to complex aortic reconstruction with the use of cardiopulmonary bypass. At the same time, the use of ceiling-mounted imaging equipment or portable C-arm fluoroscopy enables the surgeon to acquire high-resolution diagnostic imaging of the vascular system and perform life-saving therapeutic interventions.

In the case of cervical trauma, this “hybrid OR” will need to be set up to allow for efficient interactions of all team members involved. Specifically, the anesthesiologist will need to have full access to the patient’s airway, as well as one or both extremities for hemodynamic monitoring and fluid resuscitation. The OR staff will need adequate space for open surgery trays and endovascular equipment. Finally, imaging technologists should be able to maneuver the ceiling-mounted or portable imaging equipment with ease and with full access to all the required regions from head to toe.

Table 1 The Unrecognized Epidemic of Blunt Carotid Arterial Injuries: Early Diagnosis Improves Neurologic Outcome | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Management—Zone I Penetrating Injury

Patients presenting with hard signs of arterial injury at the base of the neck should be considered for immediate surgical exploration (Table 1). In stable patients, diagnostic studies are usually indicated first to fully define the location and extent of associated vascular injuries. Ultrasound has a limited role in the evaluation of vascular structures in this location due to depth of the vascular structure and the overlying rib

cage. Arteriography has been considered to be the gold standard for the diagnosis of vascular injuries in this region. Recently, dynamic contrast-enhanced CT angiography (CTA) has been used with anatomic resolution and accuracy equivalent to that of traditional arteriography. CT is rapid and allows for identification of associated injuries to the surrounding aerodigestive structures.

cage. Arteriography has been considered to be the gold standard for the diagnosis of vascular injuries in this region. Recently, dynamic contrast-enhanced CT angiography (CTA) has been used with anatomic resolution and accuracy equivalent to that of traditional arteriography. CT is rapid and allows for identification of associated injuries to the surrounding aerodigestive structures.

Open Surgical Approach

Penetrating injury to zone I can result in massive blood loss from injury to the subclavian vessels, brachiocephalic vessels, or proximal portion of the carotids. Rapid control has traditionally been performed via a sternotomy with or without cervical extension.

Vascular injury in zone I usually involves the named arterial vessel’s origin, as well as surrounding neurovascular structures. The first structure seen upon entering the mediastinum is the brachiocephalic vein. With superior and inferior retraction, one can visualize the aortic arch. From this exposure, the origins of the innominate artery, the left common carotid artery, and the left subclavian artery can be controlled, usually with vessel loops. Care is taken to identify and protect the left recurrent laryngeal and vagus nerve prior to application of vascular clamps. Partial side-biting clamps can allow for control of the great vessel origin without the need for complete aortic occlusion.

Once vascular control has been obtained, primary repair of the injured vessel can be performed. Often, this will require segmental resection to remove the devitalized vessel wall followed by a segmental interposition bypass. Due to the large caliber and flow associated with vessels in this location, prosthetic conduits are appropriate. Alternatively, panel or spiral grafts can be constructed by using a long segment of saphenous vein incised longitudinally and wrapped around a chest tube of correlating size and sutured together.

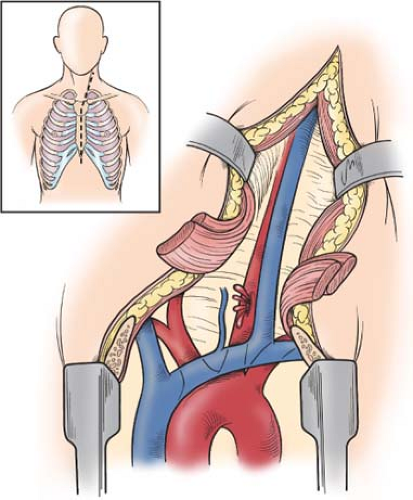

While the origin of the left common carotid artery can be seen through a midline sternotomy, distal control of this artery can be accomplished through oblique extension of the vertical sternotomy incision based on the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) as one traverses toward the cervical region (Fig. 3). The carotid sheath is located just underneath the anterior border of the SCM. Once the sheath of connective tissues is divided, one can assess the injury and determine the best plan for operative repair.

The origin of the innominate artery is also often injured in zone I. Usually, repair involves ligation of the origin with a bypass graft based off the ascending aorta. This can be done with partial side-biting clamps and does not require full cardiopulmonary bypass (Fig. 4).

In a strict open approach, the patient should be positioned as shown in Figure 5, with both arms tucked. The bilateral neck, entire chest, abdomen, bilateral groin, and upper thighs should be prepped into the field. This allows for extension of the sternotomy to the neck, laparotomy, proximal saphenous vein harvest, as well as femoral cannulation for fluid resuscitation or cardiopulmonary bypass as necessary.

A difficult and vexing problem is that of the proximal left subclavian artery. Due to its anterior to posterior course in zone I, the best surgical exposure of this vessel involves both a sternotomy for proximal control and a high anterolateral thoracotomy to gain access to the more distal portion. In this situation, the combination of both endovascular and open surgical techniques can be employed to obtain vascular control and perform the necessary open surgical repair. The patient should be taken directly to the hybrid OR where a diagnostic arteriogram can be performed to define the exact nature of the injury. Subsequent to that, the endovascular surgeon can deploy a compliant occlusion balloon for temporizing vascular control via the retrograde femoral approach. With hemorrhage control, a sternotomy is completed and the vessel exposed, the balloon replaced with a vascular clamp, and the injury repaired or ligated.

In this scenario, the arrangement shown in Figure 6 allows the surgical team to perform the initial diagnostic imaging as well as place an occlusion balloon from the femoral artery to obtain vascular control. Once this has been completed, the imaging equipment can be pulled back and the case converted to a routine open procedure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree