Vagina

Noninfectious Inflammatory Diseases

Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion (VaIN)

Invasive Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Papillary Squamotransitional Cell Carcinoma

Other Primary Malignant Tumors of the Vagina

Malignant Vaginal Tumors in Childhood

Development

The müllerian ducts first appear as funnel-shaped openings of the celomic mesothelium in the mesonephric ridge at about day 37.1 They grow caudally as paired tubes, extending to meet the posterior wall of the urogenital sinus. At about day 54, the caudal portions of the müllerian ducts fuse, forming a straight uterovaginal canal lined by simple columnar epithelium. The uterovaginal canal continues to elongate caudally until about day 66. Subsequently, the epithelium from the caudal end of the canal to the external cervical os becomes stratified squamous epithelium due to migration of squamous cells from the urogenital sinus.2 Stratification of the squamous epithelium progressively occludes the caudal portion of the canal, leading to the development of a solid vaginal plate. In the 16th week, desquamation subsequently results in the canalization of the vaginal plate. Vaginal development is essentially complete by the 18–20th week.

Anatomy

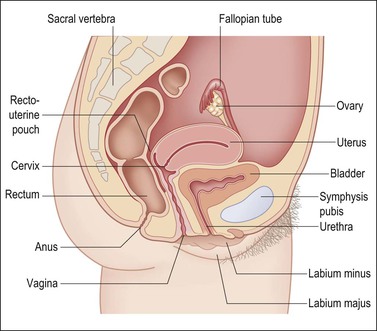

The vagina, from the Latin sheath, extends from the vestibule of the vulva to the uterine cervix, lying posterior (dorsal) to the urinary bladder and anterior (ventral) to the rectum (Figure 7.1). Its axis averages 0° with the vertical and usually more than 90° with the uterus. The ventral wall is shorter than the dorsal wall, but overall the mean vaginal length is 6.2 cm. It surrounds the exocervix and forms vault-like fornices between its cervical attachment and the lateral wall. In the adult, the anterior and posterior walls are slack and remain in contact with each other, whereas the lateral walls remain fairly rigid and separated. This gives an H-shaped appearance to the vaginal canal on cross section. The vagina opens into the vestibule formed from the urogenital sinus. The vestibule lies beneath the urethra and between the inner margins of the labia minora. The vagina, urethra, and ducts of Bartholin glands open into the vestibule.

Histology and Physiology

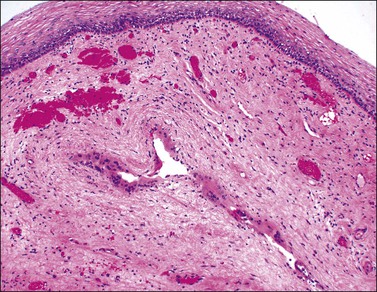

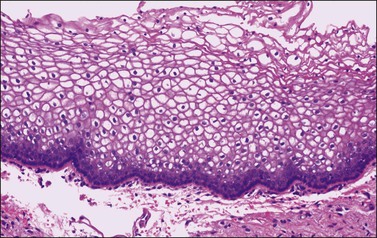

The vaginal wall consists of three principal layers: mucosa, muscularis, and adventitia (Figure 7.2). The epithelium lining of the mucosa is about 0.4 mm thick and, on gross examination, exhibits a characteristic pattern of folds or rugae separated by furrows of variable depth. The rugal pattern of the vaginal mucosa produces an undulating appearance on microscopic examination in contrast to the flat surface of the cervix. A glycogenated nonkeratinized squamous epithelium, similar to cervical epithelium, lines the luminal surface. The normal vaginal mucosa lacks glands. Its surface is lubricated both by fluids that pass directly through the mucosa and by cervical mucus. The vaginal fluid is acid (pH 4–5) owing to the presence of lactic acid produced from the metabolism of epithelial glycogen by Lactobacillus acidophilus (bacillus of Döderlein). The fluid’s acidity accounts for its considerable bacteriostatic capacity. The degree of acidity is reduced during sexual response and, more significantly, in the presence of pus or menstrual blood, or a paucity of estrogens. Before puberty and, to a lesser extent, after menopause, the vaginal mucosa is thinner and less resistant to infection than during reproductive life.

Figure 7.2 Vaginal wall. The vaginal muscularis is composed of intermixed smooth muscle bundles of variable size.

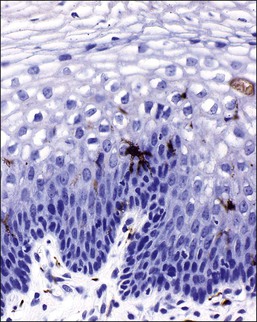

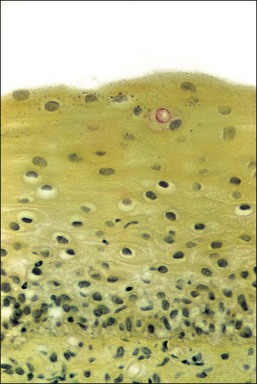

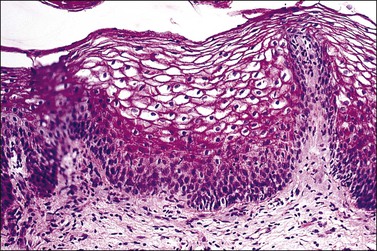

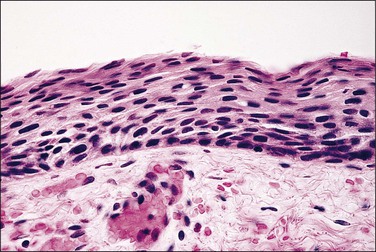

The mature, stratified squamous epithelium is arbitrarily subdivided into the deep, intermediate, and superficial zones (Figure 7.3). The deep zone contains the basal cell layer and above this the parabasal layer. Both are the active proliferative compartments or germinal beds, as shown by the nuclear proliferation markers (the Ki-67 antigen, which is demonstrable during late G1, G2, and M phases of the cell cycle) (Figure 7.4). The basal cell layer consists of a single layer of columnar-like cells, approximately 10 µm thick, the long axis of which is vertically arranged. The cells have a basophilic cytoplasm and relatively large oval nuclei. Mitoses may be present. Occasional melanocytes are also found. The parabasal layer is poorly demarcated from the overlying cell layers and consists usually of about 2–5 layers of small polygonal cells, having a total 14 µm thickness, often with intercellular bridges. The cells have basophilic cytoplasm, relatively large, centrally placed, round nuclei, and occasional mitoses.

Figure 7.3 Normal vaginal epithelium. The epithelium consists of a single layer of basal cells, several layers of parabasal cells, and thick intermediate and superficial layers of highly glycogenated cells.

Figure 7.4 Normal vagina. Ki-67 antigen, demonstrable during the late G1, G2, and M phases of the cell cycle in the parabasal and basal layer of the normal vaginal mucosa.

Cyclic changes occur in the vaginal epithelium. Proliferation of the basal layers and general thickening of the epithelium are seen in the first half of the cycle. Estrogens stimulate maturation of the epithelium, as increased numbers of intermediate cells and then superficial cells show (Figure 7.3). A sign of maturation is the significant accumulation of glycogen in the epithelium (Figure 7.5). Although glycogen is found in the intermediate and superficial cells throughout the menstrual cycle, it is particularly abundant during pregnancy. Full maturation to superficial cells does not occur when the estrogenic action is opposed by progesterone. Thus, in the second half of the cycle, after ovulation has taken place, maturation ceases at the level of the intermediate cells. This change is clinically useful; the number of superficial cells in a smear taken from the lateral vaginal wall (and, to a lesser extent, from the ectocervix) compared with the number of intermediate and parabasal cells gives a rough indication of the woman’s hormonal status. Variously calculated, although now considered archaic, this relationship gives the maturation index, the cornification index, or the karyopyknotic index (KPI). A high KPI therefore means that unopposed estrogen has stimulated the epithelium. Without hormonal stimulation, the cells atrophy. After menopause, a gradual reduction in the thickness of the epithelium occurs, first with a loss of superficial cells followed by intermediate cells. Thus, the mucosa of late menopausal women may be reduced to only 4–6 layers of parabasal cells (Figure 7.6). Consequently, a normal postmenopausal atrophic epithelium may be erroneously interpreted as a high-grade intraepithelial lesion. Exposure of the postmenopausal vagina to estrogen leads to squamous maturation comparable to that seen in the proliferative phase of reproductive age women.

Figure 7.5 Normal vaginal epithelium. Extensive glycogen (red) is present in the thick layers of intermediate and superficial cells (periodic acid–Schiff stain).

Figure 7.6 Atrophy. In the absence of estrogenic stimulation, the number of cell layers decreases, and virtually all cells are basal and parabasal with minimal cytoplasm.

The lamina propria, which lies beneath the squamous epithelium, consists of a loose fibrovascular stroma containing elastic fibers, nerves, and various mononuclear cells demonstrable by immunocytochemical methods. Dendritic processes of Langerhans cells, about 4 per HPF, are distributed throughout the mucosa.3 They are found largely in the deeper layers but can extend into the superficial fields (Figure 7.7). CD8 and, to a lesser degree, CD4 T-lymphocytes are also frequently found, whereas macrophages and B-lymphocytes are relatively uncommon.

Sometimes the superficial lamina propria discloses a band-like zone of loose connective tissue that contains atypical polygonal to stellate stromal cells with scant cytoplasm. Many cells are multinucleated or have multilobulated hyperchromatic nuclei. Few are mononucleate. Mitoses are not observed. These atypical stromal cells are thought to give rise to fibroepithelial polyps and have been observed within the cervix, vagina, and vulva. They are myofibroblastic in nature.4

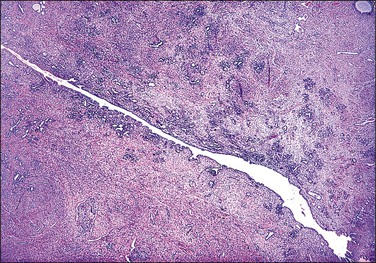

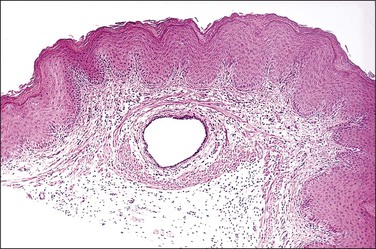

Mesonephric Ducts

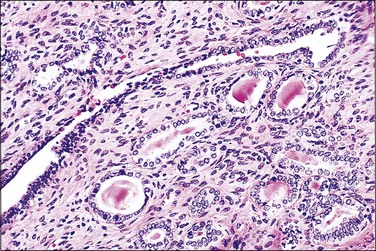

The wolffian ducts, known otherwise as ‘mesonephric ducts’ or ‘Gartner ducts,’ are vestigial in the adult female (Figure 7.8). They begin to irreversibly regress if not stimulated by testosterone before week 13 post conception. These paired ducts are most commonly seen in the lateral vaginal walls. When encountered by chance in a radical vaginectomy specimen, the ducts are virtually always invisible grossly. Microscopically, the ducts are seen often as central ducts with more peripheral arborized glands. Occasionally, the ducts appear as elongated tubes (Figure 7.9), also with peripheral arborized glands. The lumens are filled frequently with a deeply eosinophilic, hyalinized secretion (Figure 7.10). The single layer of cells lining the ducts is predominantly composed of nuclei. The cytoplasm is scant, relatively translucent, and lacks cilia. The nuclei frequently overlap. The chromatin is strikingly bland. Mitoses are absent. Individual ducts occasionally dilate and become visible cysts. In the cervix, these ducts may appear throughout the wall as mesonephric hyperplasia or even adenoma. Rarely, mesonephric adenocarcinomas arise from these vestigial structures mainly in the cervix or vagina.5

Figure 7.8 Normal mesonephric duct. On cross section it is a single duct in the submucosa surrounded by clusters of smooth muscle bands.

Developmental Disorders

Benign Effects of Diethylstilbestrol on the Vagina

Gross Structural Changes of the Vagina and Cervix

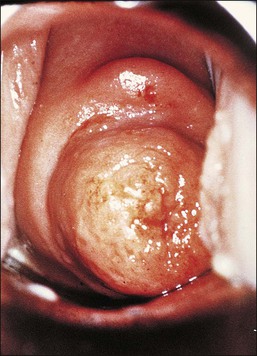

Various non-neoplastic as well as neoplastic changes occur in DES-exposed offspring. Approximately one-fifth of exposed women demonstrate gross structural changes in the cervix or vagina.6 The cervix may be hypoplastic and the vaginal fornices may be obliterated. Descriptive designations include coxcomb (hood), collar (rim), pseudopolyp, and ridge. The coxcomb is a protuberant ridge of tissue, usually on the anterior lip of the cervix, which is covered by squamous epithelium and contains cervical stroma. The collar is a low constricting band about a portion of the cervix. The pseudopolyp appears as a polyp due to the presence of a circumferential constricting groove, but in fact is a portion of cervix in which there is a central endocervical canal (Figures 7.11 and 7.12). Gross abnormalities are less common in the vagina than in the cervix. The most common is a transverse partial vaginal septum, which may make examination of the cervix by the naked eye and by colposcopy difficult or impossible. Deformities found in the upper reproductive tract include a T-shaped uterine cavity, constrictions of the uterine cavity, and hypoplasia of the uterine cavity and uterine corpus. These conditions also occur in approximately 2–4% of women who have no prenatal drug history. Over time, many structural changes disappear as the cervix remodels with age. Estimates are that upwards of two-thirds disappear after pregnancy.

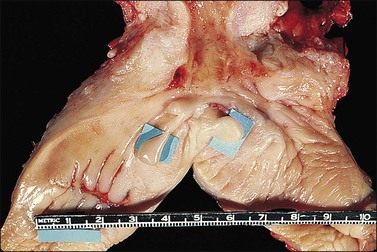

Figure 7.11 DES-associated cervical abnormalities. A coxcomb (upper) and pseudopolyp (middle) are present.

Vaginal Adenosis

Most women exposed prenatally to DES have some form of microscopic change in the inner half of the exocervix and many also have vaginal manifestations. The presence of glandular tissue in the vagina is called ‘adenosis.’ Squamous metaplasia represents the normal healing process by which adenosis transforms and heals. Ultimately the vaginal epithelial changes, when completely healed, appear as normal squamous epithelium.

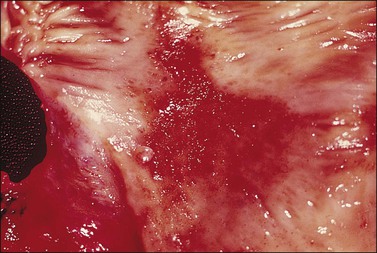

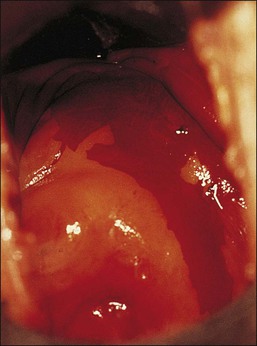

Adenosis should be suspected clinically when the vaginal mucosa discloses red granular spots or patches (Figure 7.13) or fails to stain with an iodine solution (Figure 7.14). On colposcopy, adenosis appears as glandular or metaplastic epithelium that has replaced the squamous epithelium of the vaginal mucosa. It is usually asymptomatic, although some women have vaginal discharge or postcoital bleeding.

Figure 7.14 Iodine stain of the lower genital tract. Both the cervix and portions of the vagina fail to take up the stain, indicative of a lack of glycogenated squamous epithelium.

Adenosis, with or without squamous metaplasia, involves the upper third of the vagina in 34% of DES-exposed women. The anterior wall is involved more frequently than the posterior wall. These changes extend into the middle third of the vagina in 9% and the lower third in 2% of exposed women. An embryonic form of adenosis is also encountered occasionally.7 In unexposed women, adenosis of the adult type is rare, but, when present, is identical to that which occurs in exposed women.

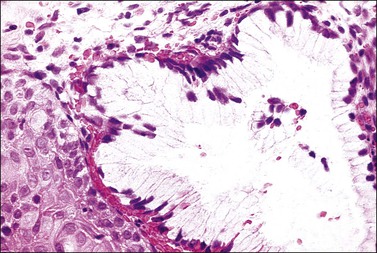

There are two adult (or differentiated) forms of adenosis: mucinous and tuboendometrial. Mucinous columnar cells, which by light and electron microscopy resemble those of the normal endocervical mucosa (Figure 7.15), comprise the glandular epithelium most frequently encountered in adenosis (62% of biopsy specimens with vaginal adenosis) and is the type of glandular epithelium most commonly seen by colposcopy. Tuboendometrial glands lined by light and dark cells, which are often ciliated and resemble the cells lining the fallopian tube and endometrium (Figure 7.16), are found in 21% of specimens with adenosis. These glands are usually found in the lamina propria and not on the surface of the vagina. The third type of adenosis is embryonic, i.e., a fetal form of adenosis (Figure 7.17). It is the putative precursor from which the adult form of adenosis develops postpubertally. It is this embryonic form that is found in up to 15% of fetuses and stillbirths and occasionally in the vagina of adult women regardless of DES history, and, experimentally, in human embryonic vagina grown in an athymic mouse host in a DES milieu.2 Remnants of columnar cells, which may be surrounded by metaplastic squamous cells or shown as intracellular droplets of mucin in metaplastic squamous cells, constitute the only evidence for adenosis in 48% of biopsy specimens (Figure 7.18).

Vaginal adenosis must be distinguished in a biopsy from endometriosis, which is also uncommon in the vagina. Apart from the presence of endometrial stroma, which is often not convincingly demonstrable, the glands of endometriosis much more closely resemble those of normal endometrium than do those of adenosis. This difference is at its most obvious during the secretory phase of the cycle. A CD10 immunoreaction may be used to confirm the presence of endometrial stroma. Another useful point in the differential diagnosis is if the glandular epithelium contains any mucinous component. This is virtually never seen in endometriosis.

Imperforate Hymen

Imperforate hymen is the most common congenital anomaly of significance to occur in the vagina, with a frequency of 0.05%. The presence of a thick mucoid secretion that distends the vagina may provide a clue to diagnosis in the neonate, but often an imperforate hymen goes unrecognized until puberty, when there is retention of menstrual detritus.8,9 If not corrected promptly, infertility may result from endometriosis and pelvic adhesions associated with retrograde menstruation.

Vaginal Agenesis

Vaginal agenesis refers to the absence or failure of large portions of the vagina to develop. Complete vaginal agenesis is rare, occurring in about 1 of 6000 live female births.10 As an isolated defect, it results from incomplete caudal development and fusion of the lower part of the müllerian ducts (müllerian dysgenesis). The external genitalia usually appear normal, except for the introitus, where a short blind pouch may be present. The epithelium is highly glycogenated and normal in all respects since, embryologically, it derives from the urogenital sinus. The defect is often associated with an absent uterus and fallopian tubes (müllerian agenesis or Mayer–Rokitansky–Kuster–Hauser syndrome), and with anomalies of the urinary tract.11–13 This syndrome provides insight into embryologic development and demonstrates that an intact mesonephric duct is required for the growth and caudal lengthening of the müllerian duct during fetal life. The gonads, not being of müllerian origin, are usually normal. About a fourth of women with vaginal agenesis have a uterus and they may have complications from retrograde menstruation (such as an increased risk of pelvic endometriosis).

Transverse Vaginal Septum

A transverse vaginal septum is uncommon,12 occurring anywhere within the vagina. Some may be related to prenatal DES exposure. A complete septum results in obstructive symptoms similar to an imperforate hymen, whereas a partial septum may allow passage of menstrual flow, but cause dyspareunia or laceration during childbirth. The microscopic appearance of the septum is typically that of a fibrovascular stroma covered on two surfaces by epithelium. The caudal surface is covered by a stratified squamous epithelium of urogenital origin, whereas the cranial aspect shows a glandular müllerian epithelium that has never transformed, as predicted from the arrested embryologic development.

Miscellaneous Congenital Disorders

Complete duplication of the vagina with a septum including muscularis extending to the introitus is rare,14 and typically accompanies cervical and uterine duplication. Longitudinal septa that lack a muscular layer are more common. They often are clinically asymptomatic. Congenital rectovaginal fistulas are often associated with an imperforate anus. Typically, the anus opens into the posterior caudal portion of the vagina, near the fourchette.

Inflammatory Disorders

Vaginitis

‘Vaginitis,’ a generic term, refers to a vaginal infection from any cause, be it yeast, parasite, or bacterial. Vaginitis, one of the most common maladies in clinical medicine, is the reason cited most often for visits to the gynecologist. The three main categories of vaginitis are related to Trichomonas vaginalis infection, Candida vaginitis, and bacterial vaginosis.15

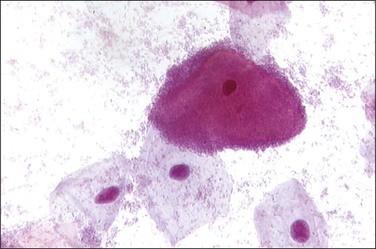

Bacterial vaginosis is the most common form of vaginitis, accounting for nearly 50% of all cases. The term ‘vaginosis’ was introduced to indicate that, unlike the specific vaginitides, there is an increased discharge without significant inflammation, as indicated by a relative absence of polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Bacterial vaginosis is not an infection by a single organism, but rather a polymicrobial overgrowth of facultative and anaerobic bacterial flora such as Mycoplasma hominis, Gardnerella vaginalis, and Mobiluncus species.16 This occurs most frequently when the pH of the vagina is no longer acid, as for example when semen is present or Lactobacillus species absent. G. vaginalis, a small Gram variable bacillus, is responsible, at least in part, for many occurrences in women of reproductive age,17 and is important in forming adherent biofilms18 that affect both genders and is sexually transmitted.19 The most important diagnostic finding is squamous cells covered with coccobacilli (‘clue cells’) (Figure 7.19).20

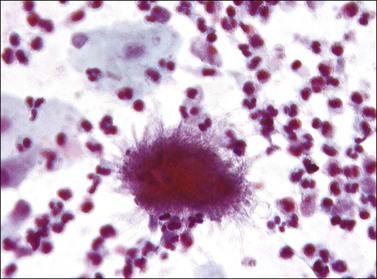

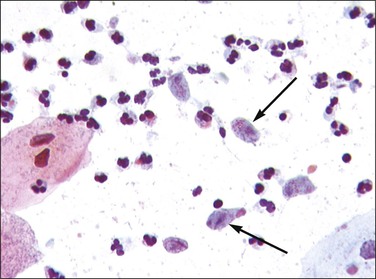

The most common cause of vaginitis throughout the reproductive period is T. vaginalis, a sexually transmitted flagellate, ovoid protozoon.21 In fresh, wet, microscopic preparations, the trichomonad shows as a motile organism with several flagella; in dry, fixed films it appears as a small (10–20 µm in diameter), eosinophilic, shield-shaped object, with poorly defined cytoplasmic and nuclear outlines (Figure 7.20). Biopsies are unusual, but show a nonspecific, chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the submucosa. The organisms ingest erythrocytes,22,23 leukocytes,23 bacilli,24 and even vaginal epithelial cells.25 The average disease is long lasting (3–5 years).26 Candida infection, often as C. albicans, is found in a high proportion of women with vaginal discharge. It produces a characteristically cheesy discharge, and its presence can be confirmed by culture, rapid vaginal yeast immunologic assay, and by its recognition in cervicovaginal smears or preparations (Figure 7.21).27 Factors associated with an increased risk of developing symptomatic Candida infection include pregnancy, oral contraceptive use, diabetes mellitus, and antibiotic use. Changes in the vaginal flora likely play a role in the development of candidiasis. In both conditions, trichomoniasis and candidiasis, a biopsy specimen is usually normal, because the organisms normally do not penetrate the mucosa or elicit an inflammatory reaction. Both may resist treatment, particularly if the male partner is not treated at the same time. Coital reinfection in that situation is frequent.

Figure 7.20 Trichomonas vaginalis. The organisms appear as small bodies that stain blue and have elongated nuclei (arrows).

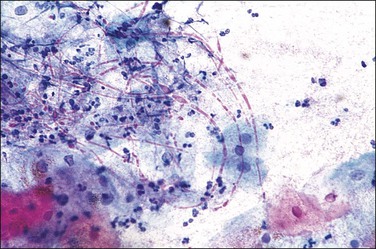

Actinomyces-like organisms are identified in cervicovaginal smears of some women who have noncopper-containing intrauterine contraceptive devices (Figure 7.22). Although sometimes associated with a true inflammatory process, more often the organism is commensal, and its presence, therefore, is of no clinical significance.

Emphysematous vaginitis is a rare self-limiting disease in which multiple gas-filled cysts are present in the submucosa of the upper vagina and sometimes extending to the ectocervix.28 It is associated with gas-forming organisms and is typically seen in pregnancy and the puerperium. Histologically, histiocytic giant cells line the gas-filled cysts (Figure 7.23), and the surrounding vaginal wall discloses scattered and a rather inconspicuous inflammatory infiltrate, rendering a picture similar to colitis cystica profunda.

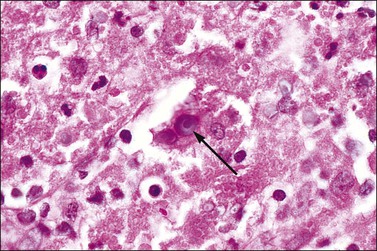

Malakoplakia

Malakoplakia is an uncommon chronic granulomatous process that most commonly affects the urinary tract, but sometimes the vagina.29 It results from defective macrophage function, manifesting as an inability to destroy ingested bacteria, usually Escherichia coli. Within masses of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, lymphocytes, and plasma cells are histiocytes that contain small laminated bodies (Michaelis–Gutmann bodies) (Figure 7.24). These basophilic structures are nuclear sized, sometimes with a bull’s eye appearance, and contain stainable iron and calcium. Ultrastructurally, they are electron dense with a variable core of lysosome-like material. The macrophages also exhibit numerous secondary lysosomes filled with partially digested bacteria and neutrophils.

Tampon-Related Lesions and Toxic Shock Syndrome

Vaginal ulcerations in tampon users have been considered a portal of entry for Staphylococcus aureus and its toxic products in patients with toxic shock syndrome (TSS). The incidence is about 6 cases per 100,000 menstruating women per year. Fever, a diffuse erythematous rash, and hypotension characterize the syndrome, which results from release of the staphylococcal toxin TSST-1 (toxic shock syndrome toxin-1) into the circulation.30 The mechanism by which tampon use during menses predisposes to TSS remains somewhat unclear, but it is believed that microulcerations of the vaginal mucosa caused by tampons permit the growth of toxin-producing staphylococci. The lesions healed spontaneously within 2–3 months after discontinuation of tampon usage. Although initially described with tampon use, postoperative cases are being reported increasingly and the syndrome may occur with any staphylococcal infection. Autopsy findings include perivasculitis, predominantly in the skin, lungs, kidneys, vagina, and other mucous membranes. The vaginal mucosa shows edema and ulceration in addition. The severity of the toxic shock syndrome varies from a mild to a rapidly fatal illness, with a mortality rate of about 4%.

Noninfectious Inflammatory Diseases

Ligneous Vaginitis

Ligneous vaginitis is a localized manifestation of a rare, inherited, and potentially life-threatening systemic disease in which affected individuals develop pseudomembranous lesions of mucosal surfaces in the acute phase.31 The disease results from mutations in the plasminogen leading to a severe type 1 plasminogen deficiency. Clinical manifestations often include ligneous conjunctivitis, ligneous gingivitis, and occasional involvement of the respiratory or gastrointestinal tract. The chronic phase is characterized by asymptomatic yellow-white to red firm masses. Histologically, these represent subepithelial accumulations of amorphic, eosinophilic material that represents fibrin and collagen,31 which may be accompanied by granulation tissue or chronic inflammatory cells.

Vaginal Cysts

Cysts derived from müllerian epithelium arise from patches of vaginal adenosis and are lined by tuboendometrial- or mucinous-type epithelia, sometimes with metaplastic squamous epithelium. They are seen most frequently in young women who were exposed prenatally to DES (as previously mentioned), but occur rarely in older women. Cysts of mesonephric (Gartner) duct origin are typically found in the lateral walls of the vagina. They are often clinically apparent cysts up to several centimeters in size, and may cause dyspareunia or other symptoms. Frequently, the mesonephric cyst has smooth muscle in its wall. The cells lining the cysts are cuboidal to columnar. The nuclei, which are large, pale, and have bland chromatin, often overlap. The cytoplasm is mucicarmine negative. Eosinophilic and mucicarmine-positive secretions are frequently present in the lumen. Occasionally, atrophic mesonephric ducts are found adjacent to the cysts, providing an additional clue to their origin.

Tumor-Like Conditions

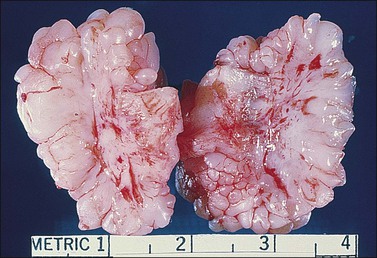

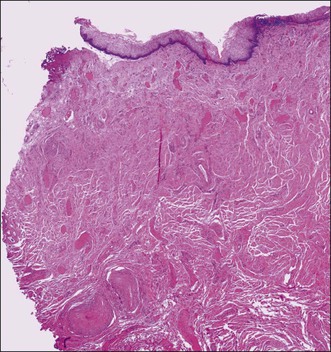

Fibroepithelial Polyps

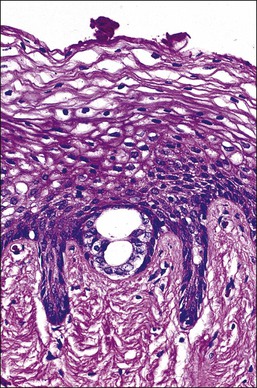

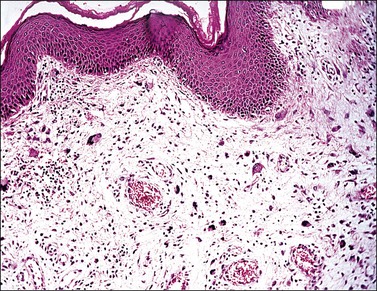

Vaginal fibroepithelial polyps are benign growths that likely arise from a stromal layer of hormone-sensitive fibroblastic or myofibroblastic cells.32–34 Cells with a similar histologic appearance have been described in a band-like subepithelial–stromal zone extending from the endocervix to the vulva of normal females, and may represent the origin of these atypical cells. The polyps commonly develop in the lower vagina of women who are pregnant or on hormone therapy, thus implicating hormonal stimulation as a causative factor. A rare example has developed in a newborn.35 Grossly, the polyps are single and solid (Figure 7.25), but occasionally villiform with finger-like rubbery projections, and up to 3 cm in size. Their surface is smooth and covered by squamous epithelium. The stroma, which is composed of loose fibroconnective tissue, may contain large atypical stromal cells with delicate, pointed cytoplasmic processes; hyperchromatic, pleomorphic, irregular nuclei; and occasionally prominent nucleoli (Figures 7.26 and 7.27). Mitotic figures are uncommon, but do occur, even with atypical forms. The cells frequently express vimentin, desmin, and receptors for estrogen and progesterone.32 In the absence of cross-striations, the stromal cells should not be called rhabdomyomatous cells. Ultrastructurally, the stromal cells resemble both fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. Fibroepithelial polyps, which are effectively treated with simple excision, should not be mistaken for a malignant growth, especially embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, which has a cambium layer, hypercellular stroma, and strap cells, often with cross-striations. Also, embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma usually occurs in children under the age of 4 years whereas most fibroepithelial polyps occur in women over the age of 20.

Figure 7.26 Fibroepithelial polyp. Large atypical stromal cells with delicate, pointed cytoplasmic processes are conspicuous.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree