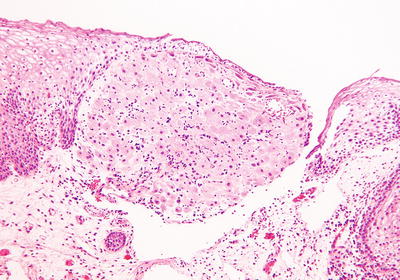

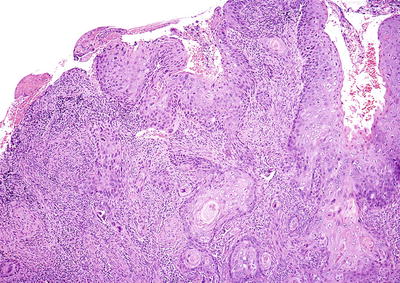

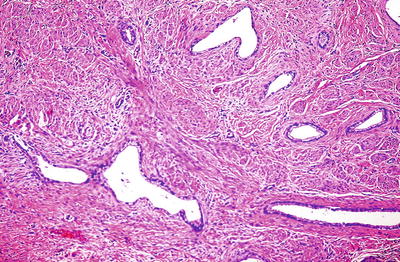

Fig. 31.1.

Papillary endocervicitis . Cervicitis with papillary growth pattern.

♦

Nuclei with finely stippled and prominent nucleoli

♦

It should not be mistaken with glandular neoplasia; absence of cellular stratification and cytologic atypia are distinguishing features from villoglandular endocervical adenocarcinoma

Infectious Cervicitis

♦

Central role in the pathogenesis of pelvic inflammatory disease and endometrial infections

♦

Primary focus in postpartum and postabortal endometritis

♦

Spontaneous abortion, premature delivery, chorioamnionitis, stillbirth, neonatal pneumonia, and septicemia have been related to bacterial infection of the cervix

Bacterial and Chlamydial Cervicitis

Clinical

♦

Most common cause of infectious cervicitis

♦

Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae are the most common causes of mucopurulent cervicitis

♦

Infection rates are greater in women of 15–21 years of age

♦

Approximately two-thirds of women are asymptomatic

♦

Associated endometritis in 40% and salpingitis in 11% of cases

♦

C. trachomatis cervicitis is most accurately diagnosed by culture or molecular diagnostic methods (PCR)

Macroscopic

♦

Yellow-green endocervical exudates

♦

Erythema and friable cervical ectropion

Microscopic

♦

Dense diffuse inflammatory exudates and acute and chronic inflammatory cell infiltrates in the stroma and epithelium

♦

Reactive squamous and endocervical epithelial atypia

♦

C. trachomatis cervicitis is a major cause of follicular cervicitis in young women

♦

Intracytoplasmic inclusions in endocervical columnar or metaplastic cells may be seen in C. trachomatis infection but are nonspecific

Actinomycosis

Clinical

♦

Actinomyces israelii is a frequent commensal organism found in the female genital tract

♦

Present in 3–27% of asymptomatic women without any risk factors

♦

Most frequently identified in women with intrauterine devices

♦

Identification of A. israelii in asymptomatic patients has little clinical significance and does not warrant therapy

♦

Rarely can be associated with pelvic abscesses

Macroscopic

♦

Yellow and granular lesions

Microscopic

♦

Branching, gram-positive filaments with peripheral palisading clubs (sulfur granules)

♦

Pseudoactinomycotic radiating granules can be identified in endocervical curettings of asymptomatic women

♦

Granulomas may be present

Tuberculosis

Clinical

♦

Typically associated with pulmonary tuberculosis and almost always secondary to tuberculous salpingitis or endometritis

Macroscopic

♦

Unremarkable or erythematous

♦

May simulate invasive carcinoma

Microscopic

♦

Caseating granulomas, but may also appear as a noncaseating granulomatous lesions

♦

Heavy lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding the granulomas

♦

Diagnosis requires identification of acid-fast Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Foreign body giant cell granulomas

♦

Lymphogranuloma venereum

♦

Sarcoidosis

♦

Schistosomiasis

Other Granulomatous Infections

♦

Syphilis, lymphogranuloma venereum, granuloma inguinale, and chancroid

♦

Clinically, all may resemble carcinoma

Herpesvirus Infection (HSV)

Clinical

♦

Caused mainly by HSV-2

♦

HSV-2 is acquired through sexual contact

♦

Up to 70% of HSV-2 infections are asymptomatic

♦

Cervical involvement is detected in 70–90% of primary infections and 15–20% of recurrent infection

♦

May result in spontaneous abortion, fetal morbidity, and mortality

♦

Diagnosed by culture, PCR, Pap smear, and serology

Macroscopic

♦

Extensive ulcerations that can be mistaken for carcinoma may occur

♦

Vulva, vagina, perineum, and cervix may be involved

Microscopic

♦

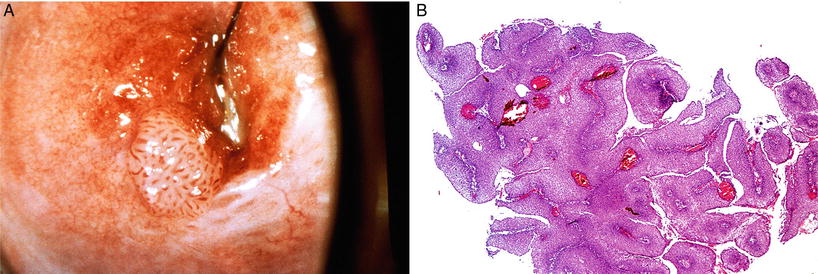

Papanicolaou smear shows large multinucleated cells with intranuclear ground glass viral inclusions (Fig. 31.2B)

♦

Cervical biopsy during the vesicular phase shows suprabasal intraepidermal vesicles filled with serum, degenerated epidermal cells, and multinucleated giant cells, some with eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions

♦

Positive staining with HSV immunostain confirms the diagnosis

Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

♦

CMV may infect endocervical epithelial or endothelial cells in either immunosuppressed or normal individuals

♦

Characteristic enlarged cells with basophilic nuclear inclusions and sometimes granular cytoplasmic inclusions

♦

Positive staining with CMV immunostain confirms the diagnosis

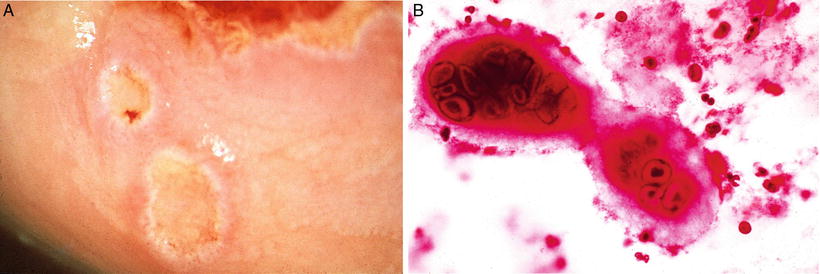

Fig. 31.2.

Herpetic cervicitis . (A) Shallow ulcers are present in the cervix. (B) Large multinucleated cell with characteristic ground glass viral inclusions in herpesvirus infection in a pap smear.

Human Papillomavirus Infection

Clinical

♦

>40 types of HPV can infect the anogenital tract

♦

The resulting infections produce a variety of gross and histological lesions

♦

Linked to a variety of cervical diseases ranging from condyloma acuminatum to invasive carcinoma and its precursors

♦

Most prevalent anogenital HPVs are divided into oncogenic risk groups

Low oncogenic risk: 6,11,42,43,44,53 (types 6 and 11 cause 90% of genital warts)

High oncogenic risk: 16,18,31,33,35,39,45,51,52,56,58,59,66 (HPV types 16 and 18 are associated with approximately 70% of all invasive cervical cancers)

Unclear oncogenic risk: 26,68,73,82

♦

Sexually transmitted infection with HPV is very common, with most women being exposed to HPV at some point. However, almost all of infected women will mount an effective immune response and clear the infection without any long-term health consequences. Women persistently infected with high-risk HPV types have an increased risk for developing a high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion or cervical carcinoma

♦

Molecular detection of HPV DNA or RNA constitutes the current gold standard for identification of HPV. Available tests detect DNA from high-risk types of HPV and specifically HPV 16 and 18

♦

Two HPV vaccines are currently available: one targets HPV types 16 and 18, the types that cause 70% of cervical cancers, and the other targets HPV types 16 and 18 plus types 6 and 11, which cause 90% of genital warts

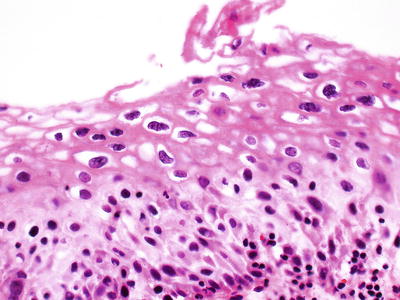

Microscopic

♦

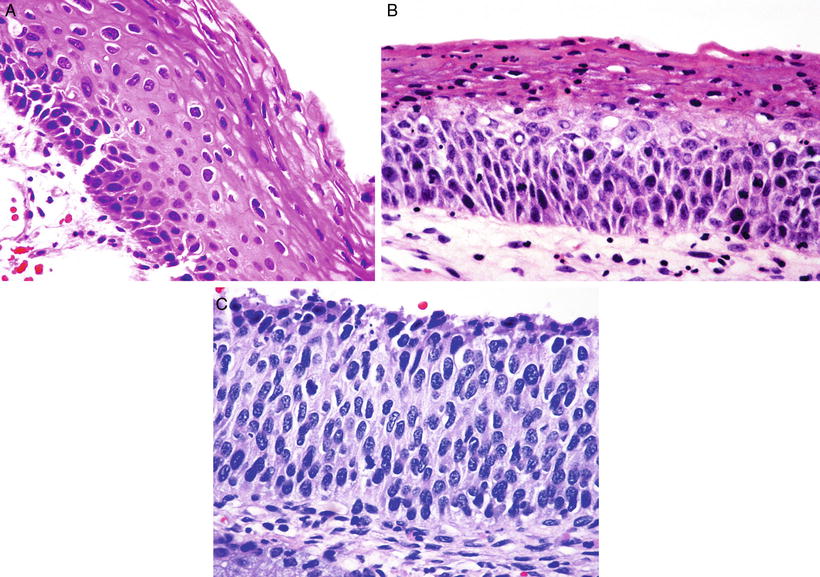

Cytopathic effects of HPV (Fig. 31.3)

Perinuclear cytoplasmic vacuolization

Nuclear atypia: enlargement, hyperchromasia, irregularity, and wrinkling of the nuclear membrane. (Koilocytosis = nuclear atypia and perinuclear vacuolization)

Anisocytosis

Binucleation and multinucleation

Fungal Diseases

♦

Mostly caused by Candida albicans

♦

Usually part of a generalized lower genital tract infection involving the vagina and vulva

♦

Antibiotic therapy, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, and immunosuppression favor fungal overgrowth

♦

Viscous vaginal discharge containing white flakes and vulvar pruritus

♦

Increased number of polymorpholeukocytes in the epithelium

♦

Fungal hyphae can be identified with PAS

Protozoal Diseases

♦

Cervical infestation by Trichomonas vaginalis is frequent

♦

Most often associated with concurrent trichomonal vaginitis

♦

Typically, a foamy yellow-green vaginal discharge is present

♦

Intense inflammatory response with prominent reparative atypia may be present

♦

Diagnosis made by wet mount, culture , and Pap smear

Parasitic Diseases

♦

Schistosomiasis (bilharziasis) caused by Schistosoma mansoni, very common in Africa (Egypt), South America, Puerto Rico, and Asia

♦

Associated with urinary schistosomiasis and sterility

♦

Noncaseating granulomas with ova, often calcified, surrounded by multinucleated giant cells

♦

May be associated with extensive pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the cervical squamous epithelium

Fig. 31.3.

Cytopathic effects of HPV .

Atypia of Repair

Clinical

♦

Can be associated with severe, acute long-standing chronic inflammation or epithelial injury

Microscopic

♦

Epithelial disorganization and nuclear atypia of the squamous and endocervical epithelium

♦

Squamous epithelium

Well-defined cytoplasmic membrane

Uniform nuclei and chromatin in prominent aggregates or clumps

Infiltration by migrating inflammatory cells

Normal mitotic figures confined to the basal and parabasal layers

Cells of the upper half of the epithelium are normal, showing orderly maturation

♦

Endocervical columnar cells

Nuclear enlargement and hyperchromasia

Irregular nuclear size and shape and smudgy chromatin

Cytoplasmic eosinophilia and loss of mucinous droplets

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Squamous intraepithelial lesion/CIN: loss of normal maturation, increased mitotic activity, and abnormal mitotic figures can be present, high-grade SIL positive for p16 immunostain

♦

Adenocarcinoma in situ: epithelial stratification, increased nuclear atypia, and mitotic figures, strongly positive for p16

Radiation-Induced Atypia

♦

May be found weeks or years after radiation

♦

Squamous cells have nuclear enlargement with abundant vacuolated cytoplasm; multinucleation may occur

♦

Changes in the endocervical glandular epithelium include cellular enlargement, loss of nuclear polarity, and dense enlarged eosinophilic nucleoli that can be multiple

♦

Fibrotic and hyalinized stroma

♦

Blood vessels often have intimal hyaline thickening and may be totally occluded

Tubal Metaplasia

Clinical

♦

Found in up to 31% of surgically excised cervices

♦

Does not appear to be related to inflammatory changes or low-grade SIL

♦

Atypical tubal metaplasia is frequently found in association with adenocarcinoma in situ

Microscopic

♦

The epithelium lining the endocervical glands is replaced by a single layer composed of admixed ciliated, nonciliated, and peg cells. The nonciliated cells may have apical snouts

♦

Bland cytologic features; absent or rare mitotic figures

♦

Typically confined to the superficial third of the cervical wall (extends <7 mm into the cervical stroma)

♦

Only slight variation in size and shape of the glands

♦

The surrounding stroma appears normal

♦

Atypical tubal metaplasia , a form of tubal metaplasia in which the glands are lined by ciliated and nonciliated cells that are crowded with larger and more hyperchromatic nuclei

Tuboendometrioid Metaplasia (TEM)

♦

Occurs commonly after cervical conization

♦

Similar to tubal metaplasia , fewer ciliated cells and nonciliated cells may have apical snouts

♦

Superficial location, minimal variation in size and shape, and lack of desmoplastic stromal response differentiate them from a neoplastic process

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Endometriosis

♦

Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS)

Cytologic atypia, significant mitotic activity, cribriforming and papillary projections

The presence of an admixture of cell types in tubal and tuboendometrioid metaplasia helps in their distinction from AIS

Tubal metaplasia and tuboendometrioid metaplasia can be focally positive for p16 but lack the diffuse and strong positivity for p16 and the high proliferation index with Ki67 evident in AIS

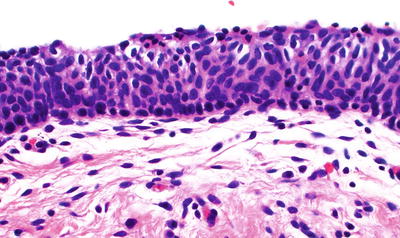

Transitional Cell Metaplasia

Clinical

♦

Typically an incidental microscopic finding, almost always in postmenopausal women, but occasionally in premenopausal women

♦

Usually seen in association with atrophy

♦

Can arise in the transformation zone, exocervix, or vagina

♦

The epithelium is composed of >10 cell layers of cells

♦

The cells have oval- to spindle-shaped nuclei, with occasional longitudinal nuclear grooves, and are oriented vertically in the deeper layers

♦

The cells in the superficial layer resemble the umbrella cells of the normal urothelium

♦

Lacks cytologic atypia and mitotic activity

♦

Immunoreactive for CK13, CK17, and CK18, similar to urothelium but lack staining for CK20

Fig. 31.4.

Transitional cell metaplasia of the cervix.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

High-grade SIL/CIN

Cytologic atypia and high mitotic activity

p16 positive and high proliferation index with Ki67 immunostain

Arias-Stella Reaction

Clinical

♦

Occurs in association with intrauterine and extrauterine pregnancies and gestational trophoblastic disease

Microscopic

♦

Can develop in endocervical glands or ectopic endometrial glands within the cervix

♦

Identical to those occurring in the endometrium

♦

Usually focal, superficial, and in the proximal portion of the endocervix

♦

Glands with markedly enlarged cells with hyperchromatic nuclei that can project into the lumen in a hobnail pattern and with vacuolated cytoplasm

♦

Rare mitotic figures

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Clear cell carcinoma

Mass lesion, stromal invasion, high mitotic rate, and classic solid, tubular, and papillary areas with hyalinized cores

♦

Adenocarcinoma in situ

More uniform nuclei , less cytoplasmic vacuolation, and increased mitoses

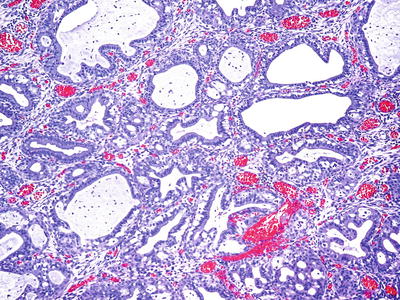

Microglandular Endocervical Hyperplasia

Clinical

♦

Benign proliferation of endocervical glands

♦

Most common in women of reproductive age, usually with history of oral contraceptive use or of pregnancy

♦

Frequently presents as an incidental finding

♦

When polypoid, associated with postcoital bleeding or spotting

Macroscopic

♦

May be polypoid, 1–2 cm

♦

Single or multiple foci

♦

Crowded glandular or tubular units of varying size lined by flattened to cuboidal cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, scant mucin and supra- or subnuclear vacuoles

♦

Predominantly uniform nuclei, with occasional pleomorphism and hyperchromasia

♦

Low mitotic activity (1 mf/10 hpf)

♦

Squamous metaplasia and subcolumnar reserve cell hyperplasia usually present

♦

Stroma is infiltrated with acute and chronic inflammatory cells

♦

Solid proliferations and signet ring cells can be present rarely

Fig. 31.5.

Microglandular hyperplasia.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Endocervical adenocarcinoma

Stromal invasion and high mitotic activity

Clear cell carcinoma usually forms an infiltrative mass and contains intracellular glycogen

♦

Endometrial adenocarcinoma with a microglandular pattern

Lack of subnuclear vacuoles

Connection with endometrial stroma, associated with presence of complex endometrial hyperplasia or mucinous metaplasia in endometrium

Nabothian Cyst

Clinical

♦

Most common cervical cyst

♦

Develops within the transformation zone secondary to squamous metaplasia covering and obstructing endocervical glands

Macroscopic

♦

Yellow-white cysts measuring up to 1.5 cm, frequently multiple

Microscopic

♦

Lined by a flattened single layer of mucin-producing (endocervical) epithelium

♦

Squamous metaplasia of the lining epithelium may occur

Tunnel Clusters

Clinical

♦

Benign collections of endocervical glands

♦

Common and become more prevalent with increasing age and also common in pregnant women

♦

Asymptomatic, incidental finding

♦

Usually located close to the surface epithelium of the cervix

♦

Cluster of closely packed glands (noncystic, lined by columnar epithelium or cystic, lined by cuboidal or flattened epithelium)

♦

Well demarcated, do not extend beyond the depth of normal endocervical glands

♦

Nuclear atypia and mitotic activity are absent

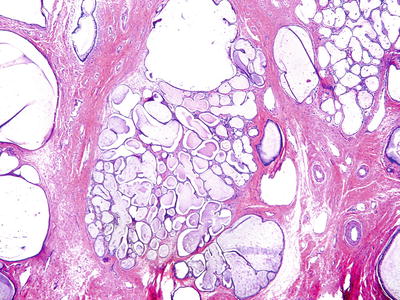

Fig. 31.6.

Endocervical tunnel clusters.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Minimal deviation adenocarcinoma of the cervix: characterized by haphazard distribution and deep stromal invasion as well as focal nuclear atypia and mitotic figures

Mesonephric Remnants and Mesonephric Hyperplasia

Clinical

♦

Vestigial elements of the distal ends of the mesonephric ducts

♦

Seen in up to 20% of cervices and prevalence is sampling dependent

♦

Commonly present in the lateral aspects of the cervix

♦

Incidental finding, almost always asymptomatic

♦

Differentiation between remnant and hyperplasia may be arbitrary and of no clinical significance

♦

Small tubules or cysts, arranged in small clusters and lined by nonciliated low columnar or cuboidal epithelium without glycogen or mucin

♦

Tubular lumen often filled with pink, homogeneous, and PAS-positive secretions

♦

May become hyperplastic (mesonephric hyperplasia) resulting in a florid tuboglandular proliferation

♦

Mitotic activity absent

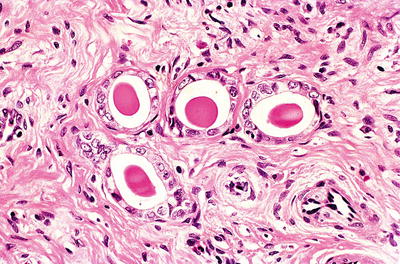

Fig. 31.7.

Mesonephric remnants . Tubules lined by cuboidal epithelium with eosinophilic luminal secretion.

Immunoprofile

♦

Typically positive for CD10, focal moderate to strong cytoplasmic positivity for p16, and low proliferation with Ki67

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Mesonephric carcinoma

Complex glandular pattern and mitoses, higher Ki67

♦

Cervical adenocarcinoma : CEA positive, strong nuclear staining with p16, and high Ki67

Endometriosis

Clinical

♦

Mechanism unknown but frequently develops following cervical trauma

♦

Large lesions may present with abnormal vaginal bleeding

Macroscopic

♦

One or more small, blue or red nodules, several millimeters in diameter

♦

Occasionally may be larger or cystic

Microscopic

♦

May be superficial (mucosal) or deep

♦

Composed of ectopic endometrial glands and stroma, resembling proliferative endometrium

♦

Rarely, the glands are secretory, and decidua may develop during pregnancy or progestin therapy

♦

In some cases, the stromal component may be sparse; CD10 may not be very helpful as endocervical stromal cells can be positive

♦

Positivity for p16 (usually patchy) and high Ki67 may be seen, BCL-2 positive

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Endocervical AIS: marked nuclear atypia, numerous apoptotic bodies, and absence of periglandular endometrial stroma

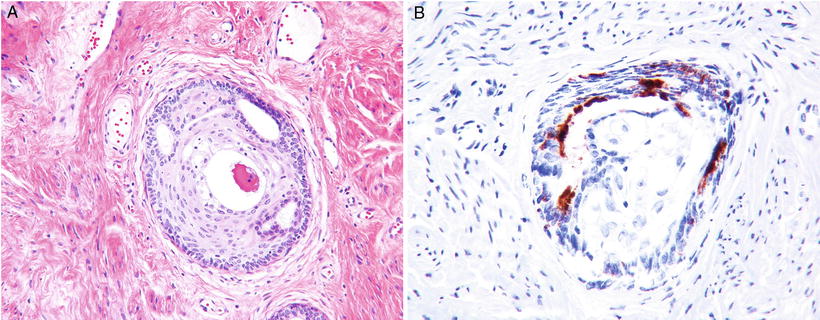

Ectopic Prostatic Tissue/Misplaced Skene’S Glands (Fig. 31.8 A–B)

Fig. 31.8.

(A) Prostatic ectopic tissue (B) PSAP immunostain.

♦

Occur in a wide age range (early 20s to >80 years of age)

♦

Currently believed to be derived from misplaced Skene’s gland, the female equivalent of male prostate gland

♦

Reportedly rare, although possibly more common as many cases may be unrecognized

♦

Usually located deep in the stroma at the transformation zone or ectocervix

♦

Characterized by a combination of glandular and squamous elements, and a double layer of glandular epithelium is present with both basal and luminal cells

♦

PSA and PSAP are usually positive; CK903 highlights the basal layer of the glandular epithelium and squamous elements

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Adenoid basal carcinomas are basaloid, show nuclear atypia of the squamous epithelium, and occur in older women

♦

Well-differentiated adenosquamous carcinomas show infiltrative pattern and cytologic atypia

Lymphoma-Like Lesion

♦

Extensive marked inflammatory lesions that may cause confusion with a lymphoproliferative lesion

♦

Composed of a superficial band of large lymphoid cells admixed with mature lymphocytes and plasma cells

♦

Features that help distinguish them from lymphoma:

Macrophages and germinal centers are commonly present

Superficial, rarely infiltrate deeper than 3 mm from the surface epithelium

Polyclonal staining pattern with immunohistochemistry

Postoperative Spindle Cell Nodule

♦

Clinically and histologically identical to those found in the vagina and vulva

♦

May develop after cervical biopsy or other traumas

♦

Actively proliferating spindle cells with oval nuclei arranged in interlacing bundles

♦

Mitotic figures are often present

♦

Neutrophils and erythrocytes are characteristic, giving an appearance of granulation tissue

Decidual Pseudopolyp and Stromal Decidualization

Clinical

♦

The cervical stroma can undergo focal decidual changes during gestation and/or progestin therapy

Macroscopic

♦

In the exocervix, it often presents as a raised plaque or pseudopolyp

Microscopic

♦

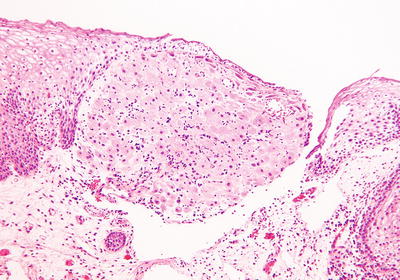

The decidual cells, present just underneath the surface epithelium, have oval bland nuclei, abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, and prominent cytoplasmic membranes (Fig. 31.9)

Fig. 31.9.

Decidual change of cervical stroma in pregnancy.

♦

Cervical polyps may also have focal and rarely massive decidual changes

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Invasive nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma: nuclear atypia, high mitotic activity, and cytokeratin positive

♦

Extruded fragments of decidua

Mesodermal Stromal Polyp (Pseudosarcoma Botryoides)

♦

Benign exophytic proliferations of stroma and epithelium

♦

Occurs more commonly in the vagina

♦

Seen most frequently in pregnant patients

♦

Composed of an edematous stroma covered by a benign-appearing, stratified squamous epithelium

♦

Stroma composed of bland-appearing plump stromal fibroblasts

♦

Focal areas of bizarre fibroblasts with hyperchromatic nuclei, occasionally multinucleated and simulating the appearance of sarcoma botryoides, may be present

♦

Cambium layer and rhabdomyoblasts are absent

Arteritis

♦

Vasculitis such as polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) or giant cell arteritis (GCA) can affect the female genital tract. PAN most commonly affects the cervix, while GCA involves all gynecologic sites with similar frequency

♦

Both types of arteritis are usually an incidental and isolated microscopic finding; however, rare cases have been associated with systemic disease and may be the initial manifestation

Epithelial Tumors and Precursors

Benign Squamous Cell Lesions

Fibroepithelial Polyp

Clinical

♦

Can occur at any age but has a predilection for pregnant women

Macroscopic

♦

Polypoid lesions , usually solitary

Microscopic

♦

Single papillary frond composed of a central fibrovascular stalk covered by mature squamous epithelium

♦

Atypia and koilocytosis are absent

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Condyloma acuminatum: koilocytosis

Squamous Papilloma

♦

Similar to squamous papillomas of the vagina and vulva

♦

Usually solitary, arising on the ectocervix or squamocolumnar junction

♦

Single papillary frond, in which mature squamous epithelium without atypia or koilocytosis lines a fibrovascular stalk and lacks the complex arborizing architecture of condylomas

Condyloma Acuminatum

Clinical

♦

One of the most common manifestations of HPV infection in the lower anogenital tract

♦

Lesions within this spectrum are designated as low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL)

♦

Usually caused by HPV types 6 and 11

♦

Commonly multifocal, spontaneous regression can occur and good response to conservative therapy

♦

Recurrences are unpredictable and may be persistent

♦

Immunosuppression may modify the natural history

♦

Increasing concern for vertical transmission during pregnancy

Microscopic

♦

Cervical condylomas are most commonly flat, but they can be papillary or show endophytic growth pattern in endocervical glands (Fig. 31.10B)

♦

Papillomatosis, acanthosis, and hyperkeratosis

♦

Koilocytosis (squamous cell with sharply demarcated perinuclear vacuolization and enlarged nucleus, with wrinkled nuclear membrane)

♦

Binucleated or multinucleated cells are frequently seen

Fig. 31.10.

(A) Condyloma acuminata , gross appearance. (B) Exophytic condyloma acuminata.

Benign Glandular Lesions

Endocervical Polyps

Clinical

♦

Very common lesion , probably not neoplastic

♦

Most often found between the fourth and sixth decades and in multigravida

♦

Commonly an incidental finding in asymptomatic women but may present with leukorrhea or abnormal bleeding due to ulceration of the surface epithelium

♦

Extremely uncommon for in situ or invasive carcinoma to arise in cervical polyps

Macroscopic

♦

Rounded or elongated with a smooth or lobulated surface

♦

Most are single, measuring between a few millimeters and 2–3 cm; rarely, they may reach gigantic proportions

Microscopic

♦

Variety of patterns according to the tissue components

♦

Most common type is the endocervical mucosal polyp, composed of mucinous epithelium that lines crypts with or without cystic changes

♦

Squamous metaplasia involving the surface or glands is often seen

♦

They may be mainly fibrous, or blood vessels may predominate (vascular polyp)

♦

The stroma is composed of loose connective tissue with centrally placed thick-walled vessels, usually infiltrated by a chronic inflammatory infiltrate

Müllerian Papilloma

Clinical

♦

Rare ; occurs almost exclusively in children; age range 1–9 years

♦

Present with bleeding or discharge

Macroscopic

♦

Usually <2 cm, polypoid to papillary mass

Microscopic

♦

Multiple small polypoid projections composed of fibrous stalks lined by simple cuboidal or columnar epithelium

♦

Occasional cells may have hobnail appearance

♦

Clear cells and mitoses are absent

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Clear cell carcinoma

♦

Sarcoma botryoides – has a more cellular stroma often forming a cambium layer subjacent to the epithelium

Squamous Tumors and Precursor Lesions

♦

Cervical carcinoma is the fourth most common cancer among females worldwide, most notable in the lower-resource countries

♦

The incidence has been declining in the last four decades in most developed countries predominantly due to cervical screening programs

♦

In contrast to cervical squamous carcinomas, adenocarcinoma of the cervix, which accounts for 10–15% of all cervical cancers, has shown an increased incidence in the last three decades

♦

HPV is the major etiologic factor in both squamous and glandular tumors

♦

Host and environmental factors contribute to enhance the probability of HPV persistence and progression to cervical neoplasia

♦

The products of two early genes, E6 and E7, have been shown to play a major role in HPV-mediated cervical carcinogenesis

♦

Increased risk is associated with increased number of sexual partners, decreased age at time of initial sexual intercourse, promiscuity of male partner, and cigarette smoking

♦

Stage is the most important prognostic factor

Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion (SIL)/Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia (CIN)

Clinical

♦

Conventionally divided into three grades: CIN 1, 2, and 3

♦

Recommendation for unified terminology for HPV lesions of lower anogenital tract to use a two-tiered nomenclature and WHO classification of squamous intraepithelial lesions: low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL/CIN1 ) and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL/CIN 2 and 3)

♦

Two-tiered nomenclature based on two patterns of HPV interaction with squamous epithelium, in one squamous epithelium supports virion production, but lesions are transient (LSIL/CIN1); second pattern leading to precancerous lesions (HSIL/CIN2–3)

♦

The goal of clinical management is to identify and treat high-grade lesions to decrease the risk of developing invasive carcinoma; not all will progress to cancer and currently it cannot be predicted which lesion will progress if not treated. The 30-year risk of progression to invasive cancer is 30–50% for untreated high-grade cervical lesions

♦

Management usually expectant for low-grade lesions/CIN1; excision of high-grade lesions (CIN 2, 3) with cone biopsy (commonly LEEP). In adolescents and young women, some guidelines promote expectant management of CIN 2 with option to follow CIN 2, but not CIN 3, reason for resistance in some cases to adopt a two-tiered terminology

Macroscopic

♦

Best evaluated by colposcopic examination after application of 3–5% acetic acid

♦

Evaluation of the surface contour, color tone, and border of the lesions

♦

The subepithelial vascular network undergoes alterations, resulting in a variety of colposcopic patterns

Microscopic

♦

Abnormal cellular proliferation with nuclear atypia that includes enlargement, pleomorphism, and irregular nuclear borders and increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios and mitotic activity that increases with severity of SIL

♦

Nuclear changes are usually present throughout the full thickness of the epithelium, irrespective of the severity of the lesion

♦

Maturation or lack of maturation of the cytoplasm in the superficial layers, coupled with persistent mitotic activity is what defines the severity of the process

♦

LSIL (CIN 1) (Fig. 31.11A)

Increased nuclear size, irregular nuclear membranes, and increased N/C ratio

Little cytoplasmic maturation in lower third of epithelium, but maturation is present in the upper two-thirds of the epithelium

Mitotic figures are present in the basal third, but not numerous; abnormal forms are rare

Diagnostic cytopathic effect of HPV (koilocytosis)

♦

HSIL (CIN 2, CIN 3) (Fig. 31.11B, C)

Maturation absent or confined to the superficial third of the epithelium

Abnormal nuclear features including increased nuclear size, irregular nuclear membranes, and increased N/C ratios with mitotic activity

Little or no cytoplasmic differentiation in the middle third and superficial thirds of the epithelium

Mitotic figures in the middle and/or superficial thirds of the epithelium and abnormal mitotic figures may be seen

♦

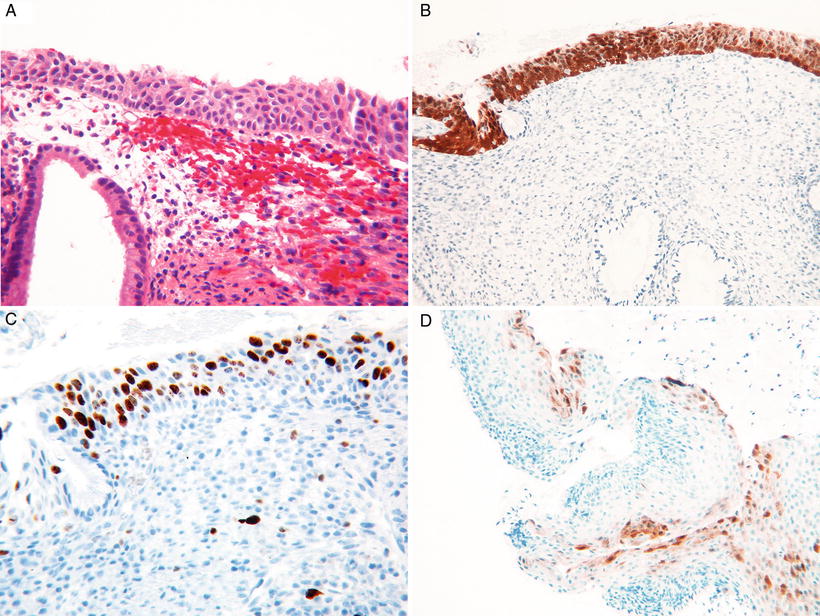

p16, biomarker recognized in the context of HPV to reflect the activation of E6/E7-driven cell proliferation and helpful in the evaluation of SILs. A cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, expressed strongly in lesions associated with high-risk HPV types. Strong and diffuse block staining for p16 supports a HSIL

p16 positive: defined as continuous strong nuclear or nuclear plus cytoplasmic staining of the basal cell layer with extension upward involving at least one-third of the epithelial thickness. Full-thickness staining or extension into the upper third or upper half is specifically not required to call a specimen positive

p16 negative: focal or patchy nuclear staining is nonspecific and can be seen with reactive squamous metaplasia, as well as low-grade lesions. Cytoplasmic staining only; wispy, blob-like, puddled, scattered, single cells; and mosaic and other patterns are defined as negative

♦

Ki67 (MIB1), a cell cycle proliferative marker, may be used as an adjunct to p16; however, recommendations for use are less well defined

In high-grade SIL, there is a high proliferation index with staining in the upper two-thirds to full thickness

In low-grade SIL, Ki67 is positive predominantly within the lower one-third of the epithelium, with occasional cells within the middle third

In normal mucosa, Ki67 is typically confined to the suprabasal cells of the lower third of epithelial cells

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Immature metaplasia: nuclear pleomorphism is absent; smooth nuclear contours and mitoses are uncommon and if present are typical and confined to the basal layers; p16 is negative and Ki67 is typically confined to the suprabasal cells of the lower third of epithelial cells

♦

Atrophic epithelium and transitional metaplasia: nuclear atypia and mitoses absent; p16 negative, and little or no proliferative activity, with only focal staining of the basal and parabasal cells with Ki67

♦

Reactive atypia: p16 negative, Ki67 should be interpreted with caution in differentiating reactive atypia from SIL since increased proliferation activity may be seen in reactive atypia

♦

Cauterized nondysplastic squamous epithelium: p16 negative and Ki67 confined to the parabasal cells

Fig. 31.11.

(A) LSIL/CIN 1 . The upper two-thirds of the epithelium show koilocytosis. (B) HSIL/CIN 2. The upper third of the epithelium shows maturation; mitoses in the basal two-thirds and nuclear abnormalities are more striking than in CIN 1. (C) HSIL/CIN 3. Nuclear abnormalities throughout the entire thickness of the epithelium and numerous mitotic figures at all levels of the epithelium.

Fig. 31.12.

(A) HSIL in immature squamous metaplasia. (B) Strong and diffuse block staining for p16. (C) High proliferation with Ki67 supporting HSIL. (D) Focal p16 staining can be seen in LSIL, p16 negative.

Early Invasive (Microinvasive/Superficially Invasive) Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Clinical

♦

Lack of agreement over diagnostic criteria, and terminology, microinvasive, early invasive, recent recommendation to use term superficially invasive squamous cell carcinoma

♦

FIGO stage IA1, not a grossly visible lesion, and stromal invasion no greater than 3 mm in depth and 7 mm or less in horizontal spread

♦

The diagnosis is always based on histologic examination that includes the entire lesion (completely excised)

♦

Lymphovascular space involvement (LVSI) does not affect stage but should be indicated in the report

♦

Lymph node metastases are uncommon (<2%) in patients with stromal invasion of 3 mm or less, in contrast to 7.6% in patients with 3.1–5 mm of invasion. The risk of lymph node metastases is higher in tumors with LVSI compared to those without it

♦

Can be treated with cone biopsy with negative margins or simple hysterectomy; treatment of cases with LVSI is individualized and in some centers treated as IA2 lesions

Macroscopic

♦

Similar to SIL(CIN) on colposcopic examination

♦

Variety of patterns including abnormal vessels

Microscopic

♦

One or more tongues of malignant cells penetrating through the basement membrane of the squamous epithelium

♦

The intraepithelial lesion is usually HSIL/CIN 3

♦

Invasive cells have increased eosinophilic cytoplasm and may show keratinization (paradoxical maturation)

♦

Loss of polarization, the margin of the invading nest has irregular contours, complex interlacing growth patterns

♦

Desmoplastic response of the adjacent stroma and often lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate

♦

Depth of invasion should be measured from the most superficial epithelial–stromal interface of adjacent intraepithelial process to deepest point of invasion; if not possible due to distortion or absent epithelium, thickness of the tumor should be measured. Invasion originating from an endocervical crypt, depth should be measured from epithelial-stromal interface of the crypt

♦

Multifocal lesions should be described

Differential Diagnosis

♦

HSIL with gland involvement

Borders of the glands involved are round and regular, and stromal desmoplastic response is absent

If luminal necrosis and intraepithelial squamous maturation within the epithelium are present, one should carefully search for microinvasion

♦

Nests of intraepithelial neoplastic epithelium disrupted and incorporated into the stroma by previous biopsy

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Clinical

♦

Uncommon before age 30 but can occur almost at any age between 17 and 90 years (mean 51.4 years)

♦

HPV DNA of specific types is detected in more than 90% of cases (HPV 16 most frequent, followed by HPV 18)

♦

Presenting symptoms depend on size and stage and include postcoital bleeding, intermittent spotting, and discharge; patients with stage I disease are usually asymptomatic

♦

Risk of nodal involvement increases with depth of invasion

♦

Stage is the most important prognostic factor; 5-year survival for stage I is 90–95%

Macroscopic

♦

May be exophytic, often as a polypoid excrescence or mainly endophytic infiltrating into surrounding structures

♦

Early lesions may present as focally indurated, ulcerated, or as granular area that bleeds readily on touch

Microscopic

♦

Considerable morphologic variation

♦

Infiltrating nests and clusters with irregular contours

♦

May infiltrate as single cells or large masses of neoplastic squamous cells

♦

Cells in the center of the invading nests frequently become necrotic or undergo extensive keratinization

♦

Individual cells are generally polygonal or oval with eosinophilic cytoplasm

♦

Nuclei vary from uniform to pleomorphic

♦

Mitotic figures common, including abnormal forms

♦

Microscopic grading based mostly on proportion of tumor undergoing keratinization: well-differentiated forms have abundant keratin pearls; moderately differentiated is more pleomorphic with rare keratin pearls, but individual cell keratinization seen; in poorly differentiated tumors, keratinization is difficult to find

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Squamous metaplasia with extensive endocervical gland involvement: significant nuclear atypia is absent, and mitotic activity is low if present at all

♦

HSIL with extensive endocervical gland involvement: borders of the involved endocervical glands are rounded and distinct and lack desmoplastic stroma

♦

Epithelioid trophoblastic tumor: generally lobulated outline, central necrosis, and the immunoprofile (placental alkaline phosphatase and human placental lactogen positivity) are helpful in making the distinction

♦

Small cell undifferentiated carcinoma: hyperchromatic molded nuclei lacking nucleoli, smudged chromatin, prominent lymphatic invasion, and negative staining with p63

♦

Marked decidual reaction; lacks atypia and mitotic activity

Histologic Types of Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Keratinizing

♦

Contain keratin pearls composed of circular whorls of squamous cells with central nests of keratin (Fig. 31.13)

♦

Intercellular bridges, keratohyalin granules, and cytoplasmic keratinization are usually observed

♦

Mitotic figures are few in a well-differentiated squamous carcinoma

Nonkeratinizing

♦

Polygonal squamous cells; individual cell keratinization may be present, but keratin pearls are absent

♦

Mitotic figures are usually numerous

Basaloid

♦

Aggressive tumor

♦

Composed of nests of immature, basal type squamous cells with scanty cytoplasm

♦

Keratin pearls are rarely present

Fig. 31.13.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix, keratinizing type.

Verrucous

Clinical

♦

Highly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma

♦

Have a tendency to recur locally after excision, but not to metastasize

Macroscopic

♦

Large bulky tumors with warty and fungating appearance

Microscopic

♦

Hyperkeratotic, undulating, warty surface, and endophytic growth

♦

Invades the underlying stroma in the form of bulbous pegs with a pushing border with a subjacent band of inflammatory infiltrate

♦

Tumor cells have abundant cytoplasm with minimal, if any, nuclear atypia or mitotic activity

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Condyloma: fibrovascular cords and koilocytosis

♦

More common types of squamous cell carcinoma: show more advanced nuclear atypia

Warty

♦

Warty surface and cellular features of HPV infection

Papillary

♦

Thin or broad papillae with connective tissue stroma covered by epithelium showing the features of SIL/CIN

♦

The underlying invasive carcinoma is usually a typical squamous cell carcinoma

Lymphoepithelioma-Like

♦

Similar to the nasopharyngeal counterpart

♦

Poorly defined islands of undifferentiated cells in a background intensely infiltrated by lymphocytes

♦

The tumor cells have uniform nuclei with prominent nucleoli and eosinophilic cytoplasm

♦

Indistinct cell borders, with a syncytial-like appearance

♦

EBV may play a role in the etiology of this tumor

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Glassy cell carcinoma

♦

Lymphoproliferative disorders

Squamotransitional Cell

♦

Rare , may be indistinguishable from transitional cell carcinomas of the urinary bladder

♦

May occur in a pure form or may contain other epithelial elements

♦

Characterized by papillary architecture with fibrovascular cores lined by a multilayered atypical epithelium resembling HSIL/CIN 3

♦

Appear to be more closely related to squamous cell carcinomas than to urothelial tumors

Glandular Tumors and Precursor Lesions

Adenocarcinoma In Situ (AIS)

Clinical

♦

Less common than SIL/CIN

♦

Average age of women with AIS is 38 years

♦

Patients are usually 1–2 decades younger than those with invasive carcinoma

♦

Risk factors similar to those of squamous lesions

♦

Occurs in association with SIL/CIN in 24–75% of cases

♦

At least 90% contain HPV; types 16 and 18 account for 80–90% of cases

Macroscopic

♦

Difficult to detect colposcopically

♦

Often superior to squamocolumnar junction

♦

No distinctive gross lesion

Microscopic

♦

Involves the surface and superficial glands in most cases and is multifocal in at least 10–15% of cases

♦

Glandular and surface epithelia lined by atypical columnar cells with elongated, cigar-shaped, hyperchromatic nuclei; the cytoplasm is reduced with minimal intracytoplasmic mucin (Fig. 31.14A, B)

♦

Cells are crowded and pseudostratified

♦

Glands may be focally, multifocally, or diffusely involved

♦

Transition between AIS and normal epithelium may be abrupt in some glands

♦

Mitotic figures, including abnormal forms and apoptotic bodies, are common

♦

Cribriform outpouchings and papillary infoldings may be seen

♦

The neoplastic glands do not extend beyond the deepest normal crypt

♦

Variant pattern of AIS referred to as SMILE (stratified mucin-producing intraepithelial lesion), characterized by stratified epithelium with cells containing mucin

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Reparative /reactive glandular atypia: nuclear clearing, lack of hyperchromasia, and minimal or no mitotic activity

♦

Reactive glandular atypia secondary to irradiation: vacuolated cytoplasm and absence of mitotic figures

♦

Adenocarcinoma with early invasion

♦

Arias-Stella reaction

♦

Microglandular hyperplasia

♦

Endometriosis

♦

Mesonephric remnants

♦

Tubal metaplasia

Early Invasive (Microinvasive) Adenocarcinoma

♦

Definition for microinvasive cervical carcinoma applies to both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma (depth of invasion of <5 mm and a horizontal measurement of <7 mm)

♦

Irregular distribution and architecture of normal endocervical crypts make the distinction between early stromal invasion and adenocarcinoma in situ very difficult

♦

Histologic patterns considered indicative of invasion:

Small detached tumor cell clusters adjacent to AIS that elicit a stromal response

Closely packed collections of glands that have lost their smooth outlines

Smooth-contoured, dilated glands with complex intraglandular cribriform or papillary growth pattern

♦

The prognosis is excellent and essentially the same as its squamous counterpart

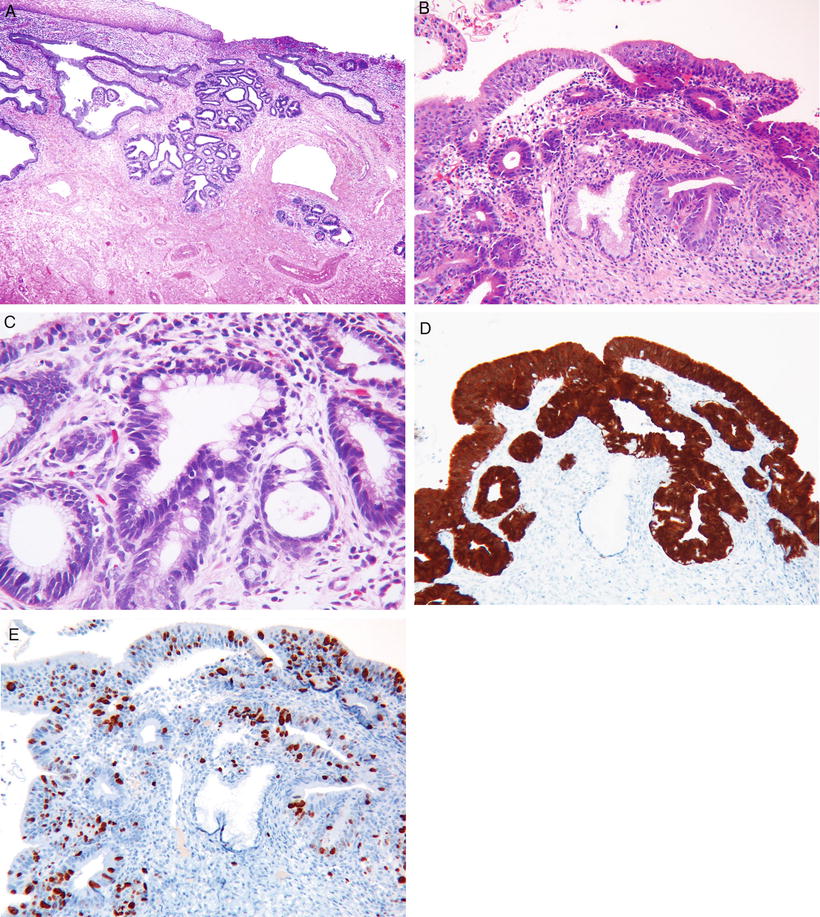

Fig. 31.14.

Adenocarcinoma in situ. (A) Low power, the involved glands maintain a lobulated architecture, (B) higher power, showing nuclear hyperchromasia and mitoses. (C) AIS intestinal type. (D) AIS strong and diffuse positivity with p16, and (E) many Ki67 positive nuclei.

Adenocarcinoma

Clinical

♦

Accounts for 15–25% of cervical carcinomas (compared to 10% 30 years ago)

♦

HPV is identified in most cases (most common types 18 and 16; some studies suggest that type 18 is more common than 16)

♦

75% of patients present with abnormal vaginal bleeding

♦

May be asymptomatic or present with vaginal discharge and pelvic pain

♦

At diagnosis, up to 85% will have stage I or stage II disease

♦

Even only superficially invasive tumors have rarely presented with ovarian metastases that mimic a primary ovarian tumor

♦

5-year survival rate for patients with negative lymph nodes has been reported to be 92% and drops to 65% for patients with positive lymph nodes

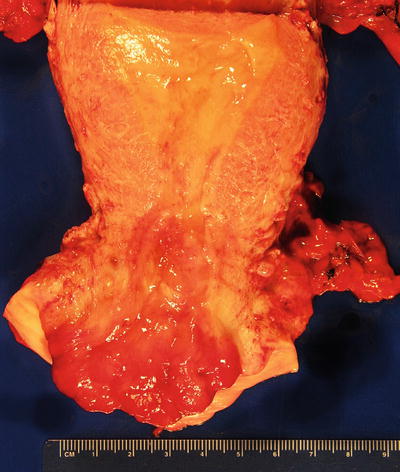

Macroscopic

♦

Majority arise in the transformation zone

♦

Fungating, polypoid, or papillary mass (Fig. 31.15); diffuse infiltration of cervical wall resulting in a barrel-shaped cervix

♦

In 15%, no gross lesion is visible

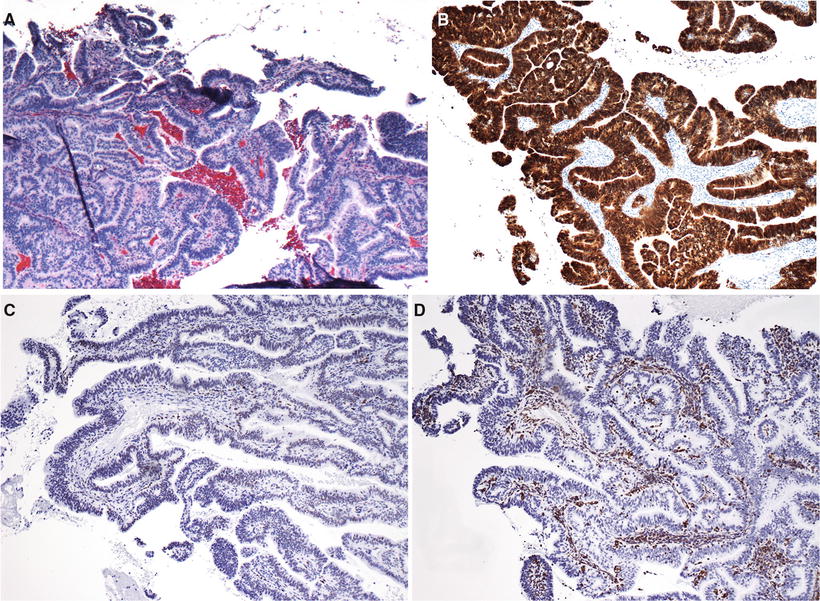

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Cervical involvement by endometrial adenocarcinoma

Site of dominant mass clinically and distribution of tumor in a fractional curettage

Presence of AIS in the cervix or endometrial hyperplasia in curettage may support one or the other

Immunohistochemistry may be useful (Fig. 31.16A–D)

Almost all endocervical adenocarcinomas show strong diffuse positivity for p16 but should be interpreted with caution particularly in small samples since endometrial carcinomas can be positive but often display a weaker intensity and focal or patchy distribution; endometrial serous carcinoma is usually intensely and diffusely positive for p16

Positivity for ER and vimentin favors endometrial carcinoma, and negativity favors endocervical adenocarcinoma

Detection of HPV DNA in ~80% of endocervical adenocarcinomas

Fig. 31.15.

Invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma.

Fig. 31.16.

(A) Endocervical adenocarcinoma. (B) Strong and diffuse positivity for p16, (C) mostly negative for ER, and (D) usually negative for vimentin.

Histologic Subtypes

Endocervical Adenocarcinoma, Usual Type

♦

Most common type, ~90%

♦

Neoplastic epithelium is pseudostratified with enlarged elongated hyperchromatic nuclei; mitotic figures present and characteristically located in apical portion (floating mitotic figures)

♦

Complex architectural patterns with mucin poor glands that exhibit cribriform or papillary architecture

♦

Strongly and diffusely p16 positive

Mucinous Carcinoma

♦

Mucinous carcinoma , gastric type

Shows gastric differentiation

An extremely well-differentiated variant is referred to as minimal deviation adenocarcinoma/adenoma malignum (Fig. 31.17)

Irregular and dilated glands or fused showing cribriform pattern invade the endocervical stroma; a desmoplastic stromal response is often absent or only minimal

Neoplastic cells with clear or pale cytoplasm, nuclei enlarged, irregular and hyperchromatic, mitotic figures present but rare

Glands extend deeper than the normal endocervical glands (>7 mm from the surface epithelium)

Most often not associated with high-risk HPV, therefore, negative or only focally positive for p16

Minimal deviation adenocarcinoma has been associated with ovarian sex cord tumors with annular tubules and Peutz–Jeghers syndrome

Mutations in the STK11 tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 19p (associated with Peutz–Jeghers syndrome) have been identified in cases of minimal deviation adenocarcinoma

♦

Mucinous carcinoma , intestinal type

Composed of cells similar to those of adenocarcinomas of the large intestine

Pseudostratified cells with only small amounts of intracellular mucin

Frequently contain goblet cells and more rarely Paneth cells

♦

Mucinous carcinoma, signet ring cell type

Rare, focal or diffuse signet ring cell differentiation

May or may not be associated with high-risk HPV

♦

Villoglandular carcinoma

Generally occurs in young women; when superficially invasive, has an excellent prognosis; recent reports suggest that some tumors can be aggressive

HPV types 16, 18, 45 most common

Surface component composed of papillae lined by one or several layers of columnar cells, some containing mucin

If intracellular mucin is absent, it is considered as the endometrioid variant

The epithelium has mild or moderate cytologic atypia; scattered mitoses are present

Usually superficially invasive, but deep invasion may occur

Endometrioid Adenocarcinoma

♦

Rare; show histologic features of endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the endometrium; however, squamous elements are less common

♦

Most associated with high-risk HPV; strongly p16 positive

♦

Rare tumors thought to arise from cervical endometriosis and not associated with HPV

Clear Cell Adenocarcinoma

♦

Rare and histologically similar to their ovarian counterparts

♦

Associated with in utero DES exposure

Serous Adenocarcinoma

♦

Rare and histologically identical to their ovarian counterparts

♦

Spread from the endometrium, ovaries, or peritoneum should be excluded

Mesonephric Adenocarcinoma

♦

Rare and arise from mesonephric remnants

♦

Tubular glands lined by mucin-free cuboidal epithelium containing eosinophilic, hyaline secretions in their lumens

♦

Other patterns include branching slit-like spaces with intraluminal fibrous papillae, sex cord-like and solid

♦

Cytologic atypia and increased mitotic activity

♦

Usually positive for cytokeratins, EMA, vimentin, calretinin, and CD10

♦

Typically negative for ER, PR, and CEA

Fig. 31.17.

Minimal deviation adenocarcinoma.

Other Epithelial Tumors

Adenosquamous Carcinoma

Clinical

♦

Accounts for 5–25% of all cervical cancers

♦

Occurs in both young and old women and can be associated with pregnancy

Macroscopic

♦

Ulcerated and nodular or polypoid

Microscopic

♦

Admixture of histologically malignant squamous and glandular cells

♦

Squamous component generally contains either keratin pearls or sheets of cells with individual keratinization

♦

Histologically recognizable glands must be present for the diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Poorly differentiated endometrial adenocarcinoma with squamous differentiation involving the cervix

♦

Collision tumor of adenocarcinoma with intraepithelial neoplasia or squamous cell carcinoma

♦

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the cervix with squamous differentiation

Glassy Cell Carcinoma

Clinical

♦

Poorly differentiated variant of adenosquamous carcinoma

♦

Accounts for <1% of cervical cancers

♦

Younger mean age (31–41 years) than patients with cervical adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma

♦

Reported to have an extremely aggressive clinical course

Macroscopic

♦

Large and produce a barrel-shaped cervix

Microscopic

♦

Uniform, large polygonal cells with finely granular ground glass-type cytoplasm

♦

Distinct cell membranes

♦

Prominent nucleoli

♦

The cells lack intercellular bridges, dyskeratosis, and intracellular collagen

♦

Abundant mitotic figures

♦

Stroma is heavily infiltrated by lymphoplasmacytic and eosinophilic inflammatory cells

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Poorly differentiated nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma: lacks ground glass cytoplasm and macronucleoli

Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma

Clinical

♦

Rare; most patients above 60 years of age

♦

Majority present with postmenopausal bleeding and mass on pelvic exam

♦

Frequently recurs locally or metastasizes to distant organs; unfavorable prognosis

Microscopic

♦

Histologic appearance similar to its counterpart in the salivary glands but with greater nuclear pleomorphism, high mitotic rate, and necrosis

♦

Characteristic spaces filled with eosinophilic hyaline material or basophilic mucin and surrounded by palisaded epithelial cells

♦

Collagen type IV and laminin positive; S-100 and HHF35 positive suggesting myoepithelial differentiation

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Small cell carcinoma; adenoid basal cell carcinoma and nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma

Clinical

♦

Rare; usually above 50 years of age

♦

Usually asymptomatic , often discovered as an incidental finding

♦

Low grade and rarely metastasizes

Microscopic

♦

Small nests of basaloid cells; the cells are small with scant cytoplasm and arranged in nests and cords with focal glandular or squamous differentiation

♦

Frequently associated with CIN or small invasive squamous cell carcinomas

Undifferentiated Carcinoma

♦

Carcinoma lacking specific differentiation

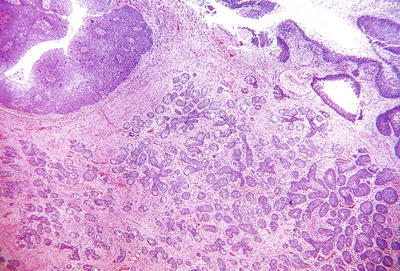

Fig. 31.18.

Adenoid basal carcinoma . Nests of tumor infiltrate the cervical stroma. Surface epithelium shows HSIL.

Neuroendocrine Tumors

Carcinoid and Atypical Carcinoid

♦

Rare

♦

Characteristic organoid appearance as seen in other sites; atypical carcinoid has cytologic atypia, increased mitotic activity (5–10 mf/10 hpf), and foci of necrosis

♦

Chromogranin and synaptophysin positive

Small Cell Carcinoma

Clinical

♦

Accounts for 1–2% of all carcinomas of the cervix

♦

Tends to occur in younger women than squamous cell carcinoma

♦

Aggressive neoplasm with early metastases

♦

Almost all found to be associated with high-risk HPV types 18 and 16, with type 18 being the most prevalent

Macroscopic

♦

Often large ulcerated lesions

♦

Frequently deeply infiltrative

Microscopic

♦

Histologically identical to their counterparts at other sites such as the lung with nuclear molding and crush artifact

♦

Sheets and cords of small anaplastic cells with scant cytoplasm, finely stippled chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli

♦

Hyperchromatic nuclei, high nuclear cytoplasmic ratio, and high mitotic rate

♦

Areas of squamous or glandular differentiation can be present and should represent <5% of the total tumor volume

♦

Necrosis common, lymphovascular invasion (LVI) present in 90% of cases and often extensive

Immunoprofile

♦

Chromogranin and synaptophysin are positive in only about 40% of the cases; therefore, negative immunostains for these markers do not exclude the diagnosis, and immunostains are not required to make the diagnosis

♦

p16 positive

♦

p63 negative

♦

TTF1 can be positive

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma composed of small cells

Lack nuclear molding and crush artifact and may have focal positivity for neuroendocrine markers

p63 may be useful for differentiating neuroendocrine carcinoma (p63 negative) from squamous cell carcinoma (p63 positive)

♦

Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with neuroendocrine features

Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma

♦

Rare tumor that often has adenocarcinomatous differen-tiation

♦

The tumor cells have abundant cytoplasm, large nuclei, and prominent nucleoli; mitoses are frequent

♦

Geographic necrosis

♦

Lymphovascular invasion often present

♦

Chromogranin and synaptophysin positive; p16 positive and p63 negative

♦

Aggressive tumors with outcome similar to that of small cell carcinoma

Mesenchymal Tumors

Smooth Muscle Tumors

Leiomyoma

♦

Most common benign mesenchymal tumor of the cervix

♦

~8% of uterine leiomyomas are primary in the cervix

♦

Usually single and produce unilateral enlargement of the cervical portion

♦

May protrude through the canal resembling an endocervical polyp

♦

Grossly and microscopically similar to those observed in the myometrium (see smooth muscle tumors of the uterine corpus)

♦

A variety of histologic patterns may be encountered

Leiomyosarcoma

Clinical

♦

Primary cervical sarcomas are extremely rare; leiomyosarcoma is the most common (<30 cases reported)

♦

Usually in perimenopausal women, most present with vaginal bleeding

Macroscopic

♦

Mass replacing and expanding the cervix or as a polypoid growth

Microscopic

♦

Hypercellular interlacing fascicles of large spindle-shaped or round cells

♦

Diffuse moderate to marked nuclear atypia

♦

High mitotic rate, including atypical forms

♦

Tumor cell necrosis

♦

Infiltrative borders and vascular invasion are common

Other Benign Mesenchymal Tumors

♦

Lipoma

♦

Hemangioma

♦

Schwannoma

♦

Paraganglioma

Other Malignant Mesenchymal Tumors

♦

Endometrial stromal sarcoma, low grade

♦

Undifferentiated endocervical sarcoma

♦

Sarcoma botryoides (embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma)

♦

Alveolar soft part sarcoma

♦

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor

♦

Osteosarcoma

Mixed Epithelial and Mesenchymal Tumors

Adenomyoma

Clinical

♦

Rare in the cervix

♦

Benign and may recur following local excision

Macroscopic

♦

Usually polypoid with a firm surface; small cystic areas may be present

♦

Rare tumors are intramural

Microscopic

♦

Consists of a benign glandular and benign mesenchymal component composed exclusively or predominantly of smooth muscle

♦

The glandular component may be lined by endocervical-type epithelium or endometrial-type glands surrounded by endometrial-type stroma

Adenofibroma

Clinical

♦

Uncommon in the cervix

♦

Benign , but recurrence may follow incomplete removal

Macroscopic

♦

Polypoid, usually protrude into the endocervical canal

♦

Small cystic spaces may be present

Microscopic

♦

Papillary fronds lined by glandular-type epithelium, cuboidal, columnar, ciliated, mucinous, or attenuated

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree