I. NORMAL GROSS AND MICROSCOPIC ANATOMY

A. Gross. The cervix is the tubular distal portion of the uterus, divided into the ectocervix and endocervix. The smooth ectocervix is covered by a reflection of the vaginal mucosa, and the anterior and posterior fornices are formed by the protrusion of the cervix into the vaginal vault. The posterior fornix is deeper than the anterior fornix. The tan, rugous endocervix is a narrow canal that begins at the external os. The external os is round and small in the nulliparous state and becomes slit-like with parity. An internal os, or isthmus, marks the transition from the endocervix to the endometrium. The parametrial soft tissue, which attaches to the lateral aspects of the cervix, contains the uterine vessels and the ureters. The posterior cervix is the anterior border of the pouch of Douglas, the space between the uterus and the rectum; the anterior cervix is immediately posterior and inferior to the bladder.

B. Microscopic. The ectocervix is generally covered by squamous epithelium in continuity with the vaginal epithelium, while the endocervix is lined by columnar mucinous epithelium. The transition from columnar to squamous epithelium through the process of squamous metaplasia occurs over a region of the cervical epithelium called the transformation zone. In states of low estrogenization, the transition occurs approximately at the external os. With higher levels of estrogen, the transition is observed on the portion of cervix visible in the vaginal vault. The transformation zone is important diagnostically because it is the site of the majority of cervical epithelial neoplasms and their precursors (e-Fig. 34.1).*

1. Squamous epithelium. The squamous epithelium is composed of a basal layer, intermediate layer, and superficial layer. The basal layer is one-cell thick and has a relatively high nuclear/cytoplasmic (N/C) ratio. The N/C ratio decreases progressively from the basal layer to the superficial layer during normal maturation, and the superficial squamous cells tend to align with their longest axis parallel to the basement membrane. Directly sampled normal squamous epithelium in cytologic preparations shows individual and clustered superficial polygonal squamous cells with pyknotic nuclei, intermediate cells with somewhat larger nuclei, and more rounded parabasal cells with the highest N/C ratios. In the estrogenized state, superficial cells predominate.

2. Columnar epithelium. The mucinous columnar epithelium of the endocervix is one cell layer thick, with basal polarization of the cells’ nuclei, little, if any, mitotic activity, and an N/C ratio of about 1:4. Mucinous columnar epithelium also lines the endocervical glands, which represent infoldings of the surface epithelium rather than true glands. Directly sampled endocervical columnar epithelium is seen in cytologic preparations as sheets of uniform round nuclei in a “honeycomb” arrangement or as single-layered strips of epithelium with basally oriented nuclei.

2. Squamous metaplastic epithelium. This is an expected finding in the transformation zone of cervical specimens. Histologically, in the immature form, the squamous epithelium underlies a layer of superficial residual columnar

epithelium (e-Fig. 34.1); with full maturation, it may appear very similar to native squamous epithelium. Metaplastic squamous cells in cytologic smears occur as either singly dispersed cells or small sheets of cells, and they show cyanophilic cytoplasm and nuclear sizes and N/C ratios between those of normal intermediate and basal cells.

II. GROSS EXAMINATION, TISSUE SAMPLING, AND HISTOLOGIC SLIDE PREPARATION. Cervical specimens for screening and diagnosis are obtained in several ways.

A. Exfoliative cytology (Pap test). See the section below on cytology of the uterine cervix for a discussion of the Pap test.

B. Biopsy. Colposcopic cervical biopsy specimens are small pieces of mucosa and superficial stroma that are taken, most often, from acetowhite areas identified visually. Documentation of the number and size of tissue fragments is important to ensure that the biopsy tissue fragments are adequately represented on the slides. If a tissue fragment exceeds 4 mm in maximal dimension, it should be bisected prior to histologic processing. In general, the biopsy tissue should be wrapped in lens paper or placed between sponges to avoid loss during processing, and the tissue should be embedded such that the microscopic sections are perpendicular to the mucosal surface. Three H&E-stained levels are prepared for microscopic examination.

C. Curettage. Curettage specimens consist of numerous and often miniscule tissue fragments in mucus, so it is imperative to both filter the contents of the container and collect any tissue that may be adherent to the pad or paper submitted within the specimen container. It is necessary to wrap curettings in lens paper to avoid loss during processing. The specimens obtained from curettage procedures should be submitted in their entirety. Three H&E-stained levels are prepared for microscopic examination.

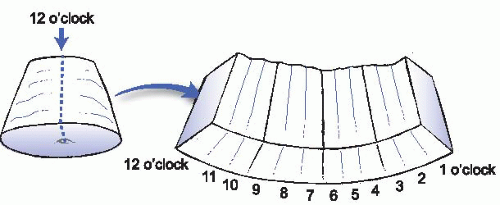

D. Conization. Ideal cold knife cone biopsy specimens consist of a single tube of ectocervix and cervical canal surrounded by stroma. Marking sutures attached by the surgeon enable the sections to be designated using the hours of the clock; by convention, the mid-anterior location is the 12 o’clock position. The endocervical margin must be identified and inked differentially from the ectocervical and stromal margins. After fixation, the specimen should be radially sectioned, with each section encompassing the endocervical margin, the mucosal surface of the endocervical canal with the transformation zone, and ectocervical margin, as shown in Fig. 34.1.

E. Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP). The key to correct processing of these specimens is identification of the endocervical margin (which may be

inked by the surgeon to facilitate identification); the ectocervix is smooth and tan-white, whereas the endocervix is tan and more rugous. The endocervical margin should be differentially inked from the ectocervical and stromal margins. Radial sections should be taken perpendicular to the mucosa, encompassing the endocervical margin, transformation zone, and ectocervical margin in the same manner as for conization specimens.

F. Radical hysterectomy

1. Uterus. Before opening the uterus, the parametrial soft tissue is inked as it represents soft tissue margins of interest. The vaginal margins are also inked. The uterus is then bivalved. If no tumor is visible or the tumor does not appear to extend into the parametrial soft tissue, the parametrial soft tissue is removed, sectioned, and completely submitted. If the vagina appears free of tumor, shave margins are submitted. If tumor appears to extend into the parametrial soft tissue or vagina, radial sections (that include the tumor’s relationship to the margin) are submitted. If a cervical mass is present, at least one section per centimeter of tumor, including the deepest extension into the cervical wall, is submitted. If no tumor is visible, the cervix is amputated and processed as a conization specimen.

2. Lymph nodes. Separate packets of pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes are typically submitted with radical hysterectomy specimens. The lymph nodes should be separated from the soft tissue and entirely submitted.

III. DIAGNOSTIC FEATURES OF COMMON NONNEOPLASTIC DISEASES

A. Inflammation and infection. Acute cervicitis is a pattern of inflammation marked by a stromal and epithelial neutrophilic infiltrate, with associated stromal edema, and, often, reactive epithelial atypia. Reactive epithelium shows enlarged nuclei and prominent nucleoli in a pattern that may be confused with neoplasia. Acute cervicitis is usually a nonspecific diagnosis, as the inciting agent can be any of a wide variety of bacterial, fungal, or protozoan organisms. Chronic cervicitis consists of a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate that is also nonspecific. Papillary endocervicitis is a term describing inflamed endocervical mucosa forming papillary structures.

1. Noninfectious cervicitis. Cervicitis can be due to irritation from chemical exposure, foreign materials (e.g., pessary, tampons), or surgical trauma. The cervix may also be a site of involvement in systemic inflammatory conditions such as collagen vascular disease. The type of inflammatory response may be neutrophilic, lymphoplasmacytic, or granulomatous.

2. Infectious cervicitis

a. Bacterial cervicitis. Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis both produce a mucopurulent cervicitis that requires additional nonhistologic methods for specific diagnosis. With chronicity, C. trachomatis infection can result in follicular cervicitis, a pattern of intense lymphocytic infiltration that characteristically includes lymphoid aggregates with germinal centers (e-Fig. 34.2). Although often associated with C. trachomatis, follicular cervicitis is not specific for that infection.

Actinomyces spp. infection is associated with intrauterine device (IUD) use and is often asymptomatic. The morphologic pattern is distinctive in that clusters of purple-red filamentous organisms are seen in curettings and smears, with associated “sulfur granules” consisting of clusters of neutrophils with a basophilic center.

Bacterial vaginosis is characterized by “clue cells,” squamous cells coated with bacterial organisms. Gardnerella vaginalis and Mobiluncus spp. are both implicated in the disease.

b. Viral cervicitis. Herpes simplex virus (HSV; primarily HSV type 2) infection is characterized by ulceration with enlarged epithelial nuclei, nuclear molding, multinucleation, and margination of the chromatin in virally

infected cells at the edge of the ulcer (e-Fig. 34.3). Cytomegalovirus is distinctive for its nuclear and cytoplasmic inclusions. Adenovirus is notable for its smudged nuclear inclusions. The poxvirus Molluscum contagiosum generates large, round, intensely eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions, as it does in its cutaneous sites. Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is closely tied to cervical neoplasia; its features are discussed in the sections on preinvasive and invasive squamous neoplasia.

c. Granulomatous cervicitis. Infectious causes of granulomatous cervicitis include Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Treponema pallidum infections. As noted above, noninfectious etiologies are also in the differential diagnosis of granulomatous inflammation.

d. Fungal. Candida spp. are commonly encountered in smears and are not necessarily always pathogenic. They cannot be speciated reliably on their morphology, in either tissue sections or cervical smears.

e. Parasitic. Trichomonas vaginalis is one of the most common causative agent of sexually transmitted infections in women. Many infections are asymptomatic. In Papanicolaou-stained smears or liquid-based preparations, an ovoid organism with an eccentric nucleus is observed; in liquid-based preparations, squamous cells may be coated with the organism.

3. Vasculitis. Most cases of vasculitis involving the gynecologic tract are incidental, and the vasculitis is often confined to the cervix. However, some cases are associated with known collagen vascular disease, and rare cases represent the first manifestation of a collagen vascular disorder (e-Fig. 34.4) (Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2000;19:258).

B. Atrophy. Epithelial atrophy is seen in the postmenopausal state, when estrogen levels are decreased. As noted in the discussion of normal histology, high estrogen states are associated with large numbers of superficial squamous cells; however, when the epithelium is thinned, the histologic picture is dominated by small cells with increased N/C ratios and nuclei at least as large or larger than those of normal intermediate cells. The overall appearance of a well-organized epithelial architecture and a lack of nuclear atypia distinguish atrophy from a severe squamous dysplasia.

C. Metaplasia. Tubal metaplasia occurs most frequently in the upper endocervix. Transitional-cell metaplasia is rare and recapitulates urothelium; it is not associated with a specific insult and must not be confused with neoplasia. Intestinal metaplasia is another uncommon metaplasia; it features columnar epithelium with goblet and Paneth cells.

D. Hyperplasia

1. Squamous hyperplasia consists of thickening of the epithelium with normal maturation. It occurs in situations of prolapse and chronic irritation.

2. Squamous papilloma is a benign squamous proliferation that covers fibrovascular cores. Squamous papilloma may be associated with HPV infection but it does not show classic koilocytic atypia.

3. Microglandular hyperplasia is an increase in glandular elements in the cervical stroma. Seen in histologic sections, the exuberant proliferation sometimes has a cribriform architecture that can raise the question of neoplasia. However, microglandular hyperplasia shows no cytologic atypia, does not infiltrate the stroma, and is not associated with a desmoplastic reaction.

4. Lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia is a benign proliferation of bland glands usually surrounding a central dilated gland and forming a well-circumscribed lobule.

5. Diffuse laminar endocervical glandular hyperplasia. In this entity, the proliferation is primarily in the very superficial aspects of the stroma and extends in a band-like fashion with an intermingled lymphocytic infiltrate that may be dense.

E. Nabothian cysts are pronounced dilatations of endocervical glands. They are extremely common (e-Fig. 34.5).

F. Endocervical tunnel clusters are superficial collections of endocervical gland ductal spaces.

G. Mesonephric remnants are developmental remnants of the mesonephric (Wolffian) duct that are occasionally identified in the deep stroma. Mesonephric remnants must not be confused with adenocarcinoma; helpful distinguishing features include the bland cytology of the lining epithelium, a lack of atypia in the overlying endocervical glands, and the absence of a desmoplastic stromal response (e-Fig. 34.6).

H. Postoperative spindle-cell nodule is a benign proliferation of fibroblasts that usually occurs following surgical manipulation.

I. Endocervical polyps are often identified colposcopically. They consist of an exophytic configuration of benign glands and stroma usually with thick-walled vessels (e-Fig. 34.7). They must be carefully examined microscopically to exclude coexisting squamous dysplasia or a glandular neoplasm.

J. Inclusion cysts are benign. Microscopically, they are filled with keratin debris and are related to surgical manipulation. Similar inclusions occur in the vagina, following episiotomies.

K. Endometriosis can involve any layer of the cervical stroma, as well as the parametrial/paracervical soft tissue.

L. Decidual change occurs in the cervical stroma during pregnancy. The nests of cells that show abundant amphophilic cytoplasm, a prominent cell border, and a single, centrally placed nucleus are usually not visible grossly, but sometimes form polyps (e-Fig. 34.8).

M. The Arias-Stella reaction, characterized by epithelial cells with nuclear enlargement and clear cytoplasm in response to progesterone, is most commonly seen in the uterine corpus in pregnancy but may also occur in the cervix. The significance of the Arias-Stella reaction lies in the fact that it can easily be confused with a glandular neoplasm.

IV. CERVICAL NEOPLASIA. The WHO classification of cervical tumors is shown in Table 34.1.

A. Benign

1. Submucosal and stromal neoplasms. Leiomyomas identical to those of the uterine corpus are also seen in the cervix.

2. Blue nevus. This benign melanocytic proliferation is common, noted clinically as a bluish discoloration of the cervical epithelium. Microscopic examination shows hyperpigmented spindle cells infiltrating the stroma in a haphazard pattern (e-Fig. 34.9).

3. Ectopic tissue. While not neoplastic, several types of ectopic tissue may be seen in the cervix. The most common types of ectopic tissue are cutaneous adnexal structures and mature cartilage. Prostatic ectopia has also been noted to occur on occasion (e-Fig. 34.10) and is important to recognize to avoid overdiagnosis of a glandular malignancy.

B. Malignant and premalignant squamous lesions. Worldwide, cervical cancer is the third most common malignancy and the fifth most common cause of cancer mortality in women. Effective screening programs have dramatically reduced deaths due to cervical cancer in the developed world, but gains have been more modest elsewhere.

The major risk factor for cervical cancer is sexually transmitted HPV infection. Although there are >40 different HPV serotypes that infect the female genital tract, high-risk serotypes (including 16, 18, 35, 39, 45, 51, 56, and 58) are associated with a markedly increased risk of severe squamous dysplasia and subsequent cervical squamous cell carcinoma. Immunodeficiency may increase the likelihood of persistent infection and may increase the risk of subsequent epithelial malignant transformation. Host factors such as smoking, concomitant sexually transmitted diseases, high parity, and oral contraceptive use may also increase the risk of malignant transformation among already infected women. For example, among women with HPV infection, smoking doubles to quadruples the odds in favor of malignant transformation (J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1406; Cancer Causes Control. 2003;14:805).

TABLE 34.1 WHO Histologic Classification of Tumors of the Uterine Cervix

Epithelial tumors

Squamous tumors and precursors

Squamous cell carcinoma, not otherwise specified

Keratinizing

Nonkeratinizing

Basaloid

Verrucous

Warty

Papillary

Lymphoepithelioma-like

Squamotransitional

Early invasive (microinvasive) squamous cell carcinoma

Squamous intraepithelial neoplasia

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN3) squamous cell carcinoma in situ

Benign squamous cell lesions

Condyloma acuminatum

Squamous papilloma

Fibroepithelial polyp

Glandular tumors and precursors

Adenocarcinoma

Mucinous adenocarcinoma

Endocervical

Intestinal

Signet-ring cell

Minimal deviation

Villoglandular

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma

Clear cell adenocarcinoma

Serous adenocarcinoma

Mesonephric adenocarcinoma

Early invasive adenocarcinoma

Adenocarcinoma in situ

Glandular dysplasia

Benign glandular lesions

Müllerian papilloma

Endocervical polyp

Other epithelial tumors

Adenosquamous carcinoma

Glassy cell carcinoma variant

Adenoid cystic carcinoma

Adenoid basal carcinoma

Neuroendocrine tumors

Carcinoid

Atypical carcinoid

Small cell carcinoma

Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma

Undifferentiated carcinoma

Mesenchymal tumors and tumor-like conditions

Leiomyosarcoma

Endometrioid stromal sarcoma, low grade

Undifferentiated endocervical sarcoma

Sarcoma botryoides

Alveolar soft part sarcoma

Angiosarcoma

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor

Leiomyoma

Genital rhabdomyoma

Postoperative spindle cell nodule

Mixed epithelial and mesenchymal tumors

Carcinosarcoma (malignant mixed Müllerian tumor)

Adenosarcoma

Wilms’ tumor

Adenofibroma

Adenomyoma

Melanocytic tumors

Malignant melanoma

Blue nevus

Miscellaneous tumors

Tumors of germ cell type

Yolk sac tumor

Dermoid cyst

Mature cystic teratoma

Lymphoid and hematopoietic tumors

Malignant lymphoma (specify type)

Leukemia (specify type)

Secondary tumors

From: Tavassoli FA, Devilee P, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics. Tumours of the Breast and Female Genital Organs. Lyon: IARC Press; 2001. Used with permission.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Uterine Cervix

Uterine Cervix

Michael E. Hull