Urinary Incontinence

KEY CONCEPTS

![]() In evaluating urinary incontinence (UI), drug-induced or drug-aggravated etiologies must be ruled out.

In evaluating urinary incontinence (UI), drug-induced or drug-aggravated etiologies must be ruled out.

![]() Accurate diagnosis and classification of UI type are critical to the selection of appropriate pharmacotherapy.

Accurate diagnosis and classification of UI type are critical to the selection of appropriate pharmacotherapy.

![]() Goals of treatment for UI are reduction of symptoms, minimization of adverse effects, and improvement in quality of life.

Goals of treatment for UI are reduction of symptoms, minimization of adverse effects, and improvement in quality of life.

![]() Nonpharmacologic, nonsurgical treatment is the first-line therapy for several types of UI, and should be continued even when drug therapy is initiated.

Nonpharmacologic, nonsurgical treatment is the first-line therapy for several types of UI, and should be continued even when drug therapy is initiated.

![]() Anticholinergic/antimuscarinic agents are first-line therapies for urge incontinence. Choice of agent should be based on patient characteristics (e.g., age, comorbidities, concurrent medications, and ability to adhere to the prescribed regimen).

Anticholinergic/antimuscarinic agents are first-line therapies for urge incontinence. Choice of agent should be based on patient characteristics (e.g., age, comorbidities, concurrent medications, and ability to adhere to the prescribed regimen).

![]() Mirabegron, a β3-adrenergic agonist, can be considered as an alternative in patients who failed to achieve optimal efficacy or cannot tolerate adverse effects of anticholinergics.

Mirabegron, a β3-adrenergic agonist, can be considered as an alternative in patients who failed to achieve optimal efficacy or cannot tolerate adverse effects of anticholinergics.

![]() Duloxetine (approved in Europe only), α-adrenergic receptor agonists, and topical (vaginal) estrogens (alone or together) are the drugs of choice for urethral underactivity (stress incontinence).

Duloxetine (approved in Europe only), α-adrenergic receptor agonists, and topical (vaginal) estrogens (alone or together) are the drugs of choice for urethral underactivity (stress incontinence).

![]() Assessment of patient outcomes should include efficacy, adverse effects, adherence, and quality of life.

Assessment of patient outcomes should include efficacy, adverse effects, adherence, and quality of life.

![]() Management of UI should target individualized goals, which may change over time. If therapeutic goals are not achieved with a given agent at optimal dosage for an adequate duration of trial, consider switching to an alternative agent.

Management of UI should target individualized goals, which may change over time. If therapeutic goals are not achieved with a given agent at optimal dosage for an adequate duration of trial, consider switching to an alternative agent.

Urinary incontinence (UI) is defined as involuntary leakage of urine.1 It is frequently accompanied by other bothersome lower urinary tract symptoms, such as urgency, increased daytime frequency, and nocturia. It is a common yet underdetected and underreported health problem that can significantly affect quality of life. Patients with UI may have depression as a result of the perceived lack of self-control, loss of independence, and lack of self-esteem, and they often curtail their activities for fear of an “accident.” UI may also have serious medical and economic ramifications for untreated or undertreated patients, including perineal dermatitis, worsening of pressure ulcers, urinary tract infections, and falls.

This chapter highlights the epidemiology, etiology, pathophysiology, and treatment of stress, urge, mixed, and overflow UI in men and women.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

UI is highly prevalent, and the impact of this condition is substantial, crossing all racial, ethnic, and geographic boundaries. In addition, associated lower urinary tract symptoms such as overactive bladder (OAB) are also quite debilitating.2 Several studies have objectively shown that UI is associated with reduced levels of social and personal activities, increased psychological distress, and overall decreased quality of life as measured by numerous indices.3 The condition can affect people of all age groups, but the peak incidence of UI, at least in women, appears to occur around the age of menopause, with a slight decrease in the age group 55 to 60 years, and then a steadily increasing prevalence after age 65 years.

Determining the true prevalence of UI is difficult because of problems with definition, reporting bias, and other methodologic issues.4 The Medical, Epidemiologic, and Social Aspects of Aging survey found that the prevalence of UI in noninstitutionalized women 60 years of age and older was approximately 38%. Almost one third of those surveyed noted urine loss at least once weekly, and 16% noted UI daily. A publication from a National Institutes of Health working group conference estimated the median level of UI prevalence to be approximately 20% to 30% during young adult life, with a broad peak around middle age (30% to 40% prevalence) and an increase in the elderly (30% to 50% prevalence).5

In the United States, chronic UI is one of the most common reasons cited for institutionalization of the elderly, and the condition is frequently encountered in the nursing home setting. Little is known about the basic differences in clinical and epidemiologic characteristics of incontinence across racial or ethnic groups. Some studies report a higher incidence of UI overall in white populations as compared with African Americans, but differences in access to healthcare as well as cultural attitudes and mores may contribute to these differences.6,7

Consistent across all studies of unselected, noninstitutionalized populations is that UI is at least half as common in men as in women.8 Overall, the prevalence of UI in men has been estimated to be approximately 9%.10 Unlike in women, the prevalence of UI in men increases steadily with age across most studies, with the highest prevalence recorded in the oldest patient cohorts.9

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Anatomy

The lower urinary tract consists of the bladder, urethra, urinary or urethral sphincter, and surrounding musculofascial structures, including connective tissue, nerves, and blood vessels. The urinary bladder is a hollow organ composed of smooth muscle and connective tissue located deep in the bony pelvis in men and women. The urethra is a hollow tube that acts as a conduit for urine flow out of the bladder. An epithelial cell layer termed the urothelium, which is in constant contact with urine, lines the interior surface of both the bladder and the urethra. Previously considered inert and inactive, the urothelium may play an active role in the pathophysiology of many lower urinary tract disorders, including interstitial cystitis and UI10 and may be a targeted location for future pharmacologic therapeutic interventions for some types of lower urinary tract dysfunction.11 The urinary or urethral sphincter is a combination of smooth and striated muscle within and surrounding the proximal portion of the urethra adjacent to the bladder. In the male, the prostate gland lies just beyond the bladder outlet and is intimately associated with the urethral sphincter. Its location accounts for both the favorable effects of pharmacological manipulation on male lower symptoms as well as the risk of UI in males following some types of prostate surgery.

To understand the principles of pharmacotherapy for UI, an understanding of the neuroanatomy and neurophysiology of the bladder and urethra is needed. The primary motor (efferent) input to the detrusor muscle of the bladder is parasympathetic and travels along the pelvic nerves emanating from spinal cord segments S2 to S4. Acetylcholine appears to be the primary neurotransmitter at the neuromuscular junction in the human lower urinary tract. Both volitional and involuntary detrusor contractions are mediated by activation of postsynaptic muscarinic receptors by acetylcholine. Of the five known subtypes of muscarinic receptors, the majority of bladder smooth muscle cholinergic receptors are of the M2 variety. In humans, the ratio of M2/M3 receptor numbers is approximately 3:1. However, M3 receptors are the subtype responsible for both emptying contractions of normal micturition as well as involuntary bladder contractions that may result in UI.10 Thus, most pharmacologic antimuscarinic therapy is primarily anti-M3 based.

Urinary Continence

To prevent incontinence during the bladder filling and storage phase of the micturition cycle, the urethra, or more accurately the urethral sphincter, must maintain adequate closure in order to resist the flow of urine from the bladder at all times until voluntary voiding is initiated. Urethral closure or resistance to flow is maintained to a large degree by the proximal (under involuntary control) and distal (under both voluntary and involuntary control) urinary sphincters. Variable contributions to urethral closure may also come from the urethral mucosa, submucosal spongy tissue, and the overall length of the urethra. During bladder filling and urinary storage, the bladder accommodates to increasing volumes of urine flowing in from the upper urinary tract without a significant increase in bladder (intravesical) pressure. The maintenance of a low intravesical pressure despite increasing volumes of urine is a unique property of the bladder and is termed compliance. In addition, bladder or detrusor smooth muscle activity is normally suppressed during the filling phase by centrally mediated neural reflexes. Normal bladder emptying occurs with opening of the urethral sphincters concomitant with a volitional bladder contraction. Bladder contraction occurs in a coordinated fashion, resulting in a rise in intravesical pressure. The rise in intravesical pressure is ideally of adequate magnitude and duration to empty the bladder to completion. Opening and funneling of the bladder outlet results in urine flow into the urethra until the bladder is emptied to near completion.

The bladder and urethra normally operate in unison during the bladder filling and storage phase, as well as the bladder emptying phase of the micturition cycle. The smooth and striated muscles of the bladder and urethra are organized during the micturition cycle by a number of reflexes coordinated at the pontine micturition center in the midbrain. Disturbances in the neural regulation of micturition at any level (brain, spinal cord, or pelvic nerves) often lead to characteristic changes in lower urinary tract function that may result in UI.12,13

Mechanisms of Urinary Incontinence

Simply stated, UI may occur as a result of abnormalities of only the urethra (including the bladder outlet and urinary sphincter) or only the bladder or as a combination of abnormalities in both. Abnormalities may result in either overfunction or underfunction of the bladder and/or urethra, with resulting development of UI. Although this simple classification scheme excludes extremely rare causes of UI such as congenital ectopic ureters and urinary fistulas, it is useful for gaining a working understanding of the condition and understanding the basis for therapeutic intervention including pharmacotherapy of various lower urinary tract disorders.

Urethral Underactivity (Stress Urinary Incontinence) This type of incontinence is characterized by brief bursts of UI concomitant with exertional activities such as exercise, running, lifting, coughing, and sneezing. The pathophysiology of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is related to decreased or inadequate urethral closure forces. In individuals with SUI, the muscular tissues surrounding the urethra that form the urethral sphincter are compromised and thus not able to resist the expulsive forces resulting from transient increases in intraabdominal pressure during physical activity. Such forces are transmitted to the bladder (an intraabdominal organ), compressing it to such an extent as to cause the egress of urine through the urethra. SUI is characterized by episodic, usually low volume urinary leakage but is clearly proportional to the amount of physical exertion or other increases in abdominal pressure such as that related to coughing and sneezing.

Risk factors for SUI in the female include pregnancy, childbirth, menopause, cognitive impairment, obesity, and aging.14,15 In males, SUI is most commonly the result of prior lower urinary tract surgery and injury to the sphincter mechanism within and external to the urethra. Radical prostatectomy for treatment of adenocarcinoma of the prostate and transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) are probably the most common proximate causes of SUI in the male. Notably, compared with its prevalence in females, SUI in males is actually quite rare.

SUI may be caused or aggravated by some pharmacologic agents such as α-antagonists and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors.16 α-Antagonists may relax the smooth muscle at the level of the urethral sphincter, resulting in a weakened closure mechanism and the onset of SUI. An adverse effect of some ACE inhibitors is chronic cough, which can also aggravate existing SUI.

Bladder Overactivity (Urge Urinary Incontinence) Urge incontinence is defined as the leakage of urine associated with urgency, a compelling desire to void.1 This is most often related to detrusor (bladder) overactivity due to involuntary bladder contractions. Bladder overactivity describes the condition in which the detrusor muscle contracts inappropriately during urinary storage that, in the neurologically normal individual, results in a sense of urinary urgency. The terms overactive bladder and detrusor (bladder) overactivity are distinct and should not be used interchangeably.

The International Continence Society defines OAB as a symptom syndrome characterized by urinary urgency, with frequency and nocturia, with/without associated UI in the absence of a known pathologic condition that may result in similar symptoms (e.g., urinary tract infection, bladder cancer).1 Frequency is defined as micturition more than eight times per day. Urgency is described as a sudden compelling desire to urinate that is difficult to delay.1 People suffering from OAB typically have to empty their bladder frequently, and, when they experience a sensation of urgency, they may leak urine if they are unable to reach the toilet quickly. Many patients have associated nocturia (>1 micturition per night) and/or nocturnal incontinence (enuresis). Patients with urge urinary incontinence (UUI) often experience high-volume urine leakage when it occurs. Although detrusor overactivity may be related to OAB, the former diagnosis requires urodynamic testing while the latter is symptomatically defined.

Most patients with OAB and UUI have no identifiable underlying etiology and thus are classified as “idiopathic.” Patients with a relevant neurologic condition and with UI related to involuntary bladder contractions demonstrated on urodynamic testing are classified as having neurogenic detrusor overactivity. Clearly identifiable risk factors for UUI include normal aging, neurologic disease (including stroke, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and spinal cord injury), and bladder outlet obstruction (e.g., due to benign prostatic hyperplasia [BPH] or prostate cancer).

The pathophysiology of OAB and UUI is not well understood but is likely related to either neurogenic or myogenic factors or combination of both.17 A full discussion of these differences is complex and beyond the scope of this chapter. However, in practice, although the cause of UUI is difficult to define, the treatment is identical regardless of etiology and pathophysiology.

Some pharmacologic agents may cause or aggravate UUI. Diuretics will cause the rapid accumulation of urine in the bladder with resulting urinary urgency and frequency that can result in UUI. Alcohol will have similar effects. Anticholinesterase inhibitors may also produce urgency and frequency.

Urethral Overactivity and/or Bladder Underactivity (Overflow Incontinence) Overflow incontinence is urinary leakage resulting from an overfilled and distended bladder that is unable to empty. This type of UI occurs when the bladder is filled to capacity at all times but is unable to empty, causing urine to leak from a distended bladder past a normal or even overactive sphincter. Another term related to overflow incontinence is chronic urinary retention.

Overflow incontinence is the result of urethral overactivity, bladder underactivity, or a variable combination of both. Clinically and practically, the most common causes of urethral overactivity in men are anatomic urethral obstruction, including that due to BPH and prostate cancer. In women, urethral overactivity is rare but may result from cystocele formation (with resultant kinking or obstruction of the urethra) or surgical overcorrection following surgery for the repair of SUI (iatrogenic obstruction). In both men and women, overflow UI may be associated with systemic neurologic dysfunction or diseases, such as spinal cord injury or multiple sclerosis.

Bladder underactivity occurs as a result of the detrusor muscle of the bladder becoming progressively weakened and eventually losing the ability to voluntarily contract and expel urine during voiding. In the absence of adequate contractility, the bladder is unable to empty completely, and large volumes of residual urine are left after voiding. Both myogenic and neurogenic factors have been implicated in producing the impaired contractility seen in this condition. Clinically, overflow incontinence is most commonly seen in the setting of long-term chronic bladder outlet obstruction in men, such as that due to BPH or prostate cancer, diabetes mellitus, or denervation due to radical pelvic surgery, such as abdominopelvic resection or radical hysterectomy.

There are numerous pharmacologic agents that can result in urinary retention and overflow incontinence. Agents that increase urethral resistance or closure pressure include α-agonists and tricyclic antidepressants. Over-the-counter cold and cough remedies as well as diet pills may contain agents with α-adrenergic properties and/or antihistaminic properties that can result in voiding dysfunction and urinary retentions. Agents that can decrease bladder contractility include anticholinergics, tricyclic antidepressants, calcium channel blockers, narcotic analgesics, and antipsychotics.

Mixed Incontinence and Other Types of Urinary Incontinence Various types of UI may coexist in the same patient. The combination of bladder overactivity and urethral underactivity is termed mixed incontinence. The diagnosis is often difficult because of the confusing array of presenting symptoms. Bladder overactivity may also coexist with impaired bladder contractility. This occurs most commonly in the elderly and is termed detrusor hyperactivity with impaired contractility.18

Functional incontinence is not caused by bladder- or urethra-specific factors. Rather, in patients with conditions such as dementia or cognitive or mobility deficits, the UI is linked to the primary disease process more than any extrinsic or intrinsic deficit of the lower urinary tract. An example of functional incontinence occurs in the postoperative orthopedic surgery patient. Following extensive orthopedic reconstructions such as total hip arthroplasty, patients are often immobile secondary to pain or traction. Therefore, patients may be unable to access toileting facilities in a reasonable amount of time and may become incontinent as a result. Treatment of this type of UI may involve simple interventions such as placing a urinal or commode at the bedside that allows for uncomplicated access to toileting. Pharmacologically, functional incontinence can be induced by sedative-hypnotics, narcotic analgesics, and other medications with cognitive adverse effects.

Many localized or systemic illnesses may result in UI because of their effects on the lower urinary tract or the surrounding structures:

1. Dementia/delirium

2. Depression

3. Urinary tract infection (cystitis)

4. Postmenopausal atrophic urethritis or vaginitis

5. Diabetes mellitus

6. Neurologic disease (e.g., stroke, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury)

7. Pelvic malignancy

8. Constipation

9. Congenital malformations of the urinary tract

![]() As noted above, many commonly used medications may precipitate or aggravate existing voiding dysfunction and UI (Table 68-1).19

As noted above, many commonly used medications may precipitate or aggravate existing voiding dysfunction and UI (Table 68-1).19

TABLE 68-1 Medications That Influence Lower Urinary Tract Function

CLINICAL PRESENTATION Urinary Incontinence Related to Urethral Underactivity

Generally, SUI is considered the most common type of UI and probably accounts for at least a portion of UI in more than half of all incontinent women. Some studies have found that mixed UI (SUI plus UUI) is the most common type of UI. However, the proportions of SUI, UUI, and mixed UI vary considerably with age group and gender of patients studied, study methodology, and a variety of other factors.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

![]() UI may present in a number of ways, depending on the underlying pathophysiology. A complete medical and medication history, including an assessment of symptoms and a physical examination, is essential for correctly classifying the type of incontinence and thereby assuring appropriate therapy.

UI may present in a number of ways, depending on the underlying pathophysiology. A complete medical and medication history, including an assessment of symptoms and a physical examination, is essential for correctly classifying the type of incontinence and thereby assuring appropriate therapy.

Urine Leakage

UI represents a spectrum of severity in terms of both volume of leakage and degree of bother to the patient. It is important to carefully consider the level of patient discomfort and bother when discussing urine leakage as each individual may or may not desire therapy. A careful and complete history during the patient interview is essential to accurately determine the precise nature of the problem. The onset, nature, timing, and volume of incontinence are recorded as is the use of pads. Use of absorbent products, such as panty liners, pads, or briefs, is an important point of discussion, but the clinician must keep in mind that use of these products varies among patients. The number and type of pads may not relate to the amount or type of incontinence, as their use is a function of personal preference and hygiene. A high number of absorbent pads may be used every day by a patient with severe, high-volume UI or, alternatively, by a fastidiously hygienic patient with low-volume leakage who simply changes pads often to prevent wetness or odor. Nevertheless, a large number of pads that are described by the patient as “soaked” is indicative of high-volume urine loss.

Regardless of the volume of urine loss, the desire to seek evaluation for UI in the majority of patients is most commonly elective and therapy is often contingent on the degree of bother to the individual patient. As with the use of absorbent products, patients differ with regard to the amount of urine loss they will tolerate before considering the condition bothersome enough to seek assistance. However, it is critically important that in some individuals new-onset UI may be the first manifestation of an undiagnosed illness, or may occur as a result of treatment or drug therapy of an unrelated condition. It is these individuals who mandate a full evaluation and treatment.

Symptoms

Under the best of circumstances, UI is difficult to categorize based on symptoms alone (Table 68-2).20 In a study of patients who appeared to have SUI based on symptoms and patient history, urodynamics showed that only 72% of patients had SUI as the sole cause of incontinence.21

TABLE 68-2 Differentiating Bladder Overactivity from Urethral Underactivity-Related UI

Patients with SUI characteristically complain of urinary leakage with physical activity. Volume of leakage is proportional to the level of activity. They will often leak urine during periods of exercise, coughing, sneezing, lifting, or even when rising from a seated to a standing position. Patients with pure SUI will not have leakage when physically inactive, especially when they are supine. Often they will have little or no UI at night, will not awaken to void during the night (nocturia), will not wet the bed, and often do not even wear absorbent products during the night. Urinary urgency and frequency may be associated with SUI, either as a separate component caused by bladder overactivity (mixed incontinence) or as a compensatory mechanism wherein the patient with SUI learns to toilet frequently to prevent large-volume urine loss during physical activity.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION Urinary Incontinence Related to Bladder Overactivity

CLINICAL PRESENTATION Overflow Incontinence (Chronic Urinary Retention)

Typical symptoms of UUI and bladder overactivity include frequency, urgency, and high-volume incontinence. Nocturia and nocturnal incontinence are often present. Urine leakage is unpredictable, and the volume loss may be quite large. Patients often wear protection both day and night. Urinary frequency can be affected by a number of factors unrelated to bladder overactivity, including excessive fluid intake (polydipsia) and bladder hypersensitivity states such as interstitial cystitis and urinary tract infection. In some patients, bladder overactivity manifests as UI without awareness in the absence of a sense of urinary urgency or frequency. Urinary urgency, a sensation of impending micturition, requires intact sensory input from the lower urinary tract. In patients with spinal cord injury, sensory neuropathies, and other neurologic diseases, a diminished ability to perceive or process sensory input from the lower urinary tract may result in bladder overactivity and UI without urgency or urinary frequency. When bladder contraction occurs without warning and sensation is absent, the condition is referred to as reflex incontinence.

Patients with overflow incontinence may present with lower abdominal fullness as well as considerable obstructive urinary symptoms, including hesitancy, straining to void, decreased force of urinary stream, interrupted stream, and a vague sense of incomplete bladder emptying. These patients may also have a significant component of urinary frequency and urgency. In patients with acute urinary retention and overflow incontinence, lower abdominal pain may be present. Although these symptoms are not specific for overflow incontinence, they may warrant further investigation, including an assessment of postvoid residual urine volume.

Signs

A presenting complaint of UI mandates a directed physical examination and a brief neurologic assessment. The workup ideally includes an abdominal examination to exclude a distended bladder, neurologic assessment of the perineum and lower extremities, pelvic examination in women (looking especially for evidence of prolapse or hormonal deficiency), and genital and prostate examination in men. Perineal skin maceration, erythema, breakdown, and ulceration may be indicative of chronic, severe UI. Patients with chronic incontinence may also manifest fungal infections of the skin of the perineum and upper thighs.

SUI can usually be objectively demonstrated by having the patient cough or strain during the examination and observing the urethral meatus for a sudden spurt of urine. In women, SUI may be associated with varying degrees of vaginal prolapse, including cystourethrocele (bladder and urethral prolapse).

In both men and women, digital rectal examination provides an opportunity to check ambient rectal tone and the integrity of the sacral reflex arc (e.g., anal wink) as well as assess the patient’s ability to perform a voluntary pelvic floor muscle contraction (i.e., Kegel exercise), which may be an important factor in deciding on appropriate therapy. In men, a digital examination of the prostate assesses for the presence of prostate cancer, inflammation, and BPH.

A targeted neurologic examination includes assessment of reflexes, rectal tone, and sensory or motor deficits in the lower extremities, which might be indicative of systemic or localized neurologic disease. Neurologic diseases have the potential to affect bladder and sphincter function and thus may have significant implications in the incontinent patient.

Prior Medical or Surgical Illness

UI may present in the setting of concurrent, seemingly unrelated illnesses. New-onset UI may be the initial manifestation of systemic illnesses such as diabetes mellitus, metastatic malignancies, and neurologic diseases such as Parkinson’s disease, brain tumors, and multiple sclerosis. CNS disease, or injury above the level of the pons, generally results in symptoms of bladder overactivity and UUI. Spinal cord injury or disease may manifest as bladder overactivity and UUI or as overflow incontinence, depending on the spinal level and completeness of the injury or disease.

Medications may have wide-ranging effects on lower urinary tract function (see Table 68-1). A thorough inquiry into the use of new medications in the setting of recent-onset UI may show a relationship.

Acute UI manifesting in the immediate postoperative setting may be secondary to a number of factors, including surgical manipulation and immobility, and to a number of medications, especially opioid analgesics and sedative-hypnotics.

Prior surgery may have effects on lower urinary tract function. UI following prostate surgery in men is highly suggestive of injury to the sphincter and resultant SUI. Pelvic surgery for benign and malignant conditions may result in denervation or injury to the lower urinary tract. This includes bowel surgery and gynecologic procedures. For example, new-onset total UI following gynecologic surgery suggests intraoperative bladder injury and subsequent development of a postoperative vesicovaginal fistula. Radiation therapy to the pelvis for malignant disease (e.g., prostate cancer or cervical cancer) may result in injury to the bladder or urethra and subsequent UI.

In women, UI may be related to several gynecologic factors, including childbirth, hormonal status, and prior gynecologic surgery although recently the relationship of some of these factors to UI has come under debate.22 Pregnancy and childbirth, particularly vaginal delivery, are associated with SUI and pelvic prolapse. Significant SUI in the nulliparous woman is uncommon. UI that becomes progressive at or around menopause suggests a hormonal component that may be responsive to estrogen or hormone replacement therapy.

UI may present in the setting of other significant pelvic floor disorders, signs, and symptoms. Constipation, diarrhea, fecal incontinence, dyspareunia, sexual dysfunction, and pelvic pain may be related to UI. A history of gross hematuria in the setting of UI mandates further urologic investigation, including radiologic imaging of the upper urinary tract and cystoscopy. Acute dysuria with or without hematuria in the setting of UI suggests cystitis. Urinalysis and urine culture should be performed in these patients.

TREATMENT

Desired Outcomes

![]() The efficacy goals for the management of UI include restoration of continence, reduction of the number of UI episodes, and prevention of complications (pressure ulcers, nursing home placement, etc.). Other desired outcomes are minimization of adverse treatment consequences and cost, as well as improvement in patient’s quality of life.

The efficacy goals for the management of UI include restoration of continence, reduction of the number of UI episodes, and prevention of complications (pressure ulcers, nursing home placement, etc.). Other desired outcomes are minimization of adverse treatment consequences and cost, as well as improvement in patient’s quality of life.

General Approach to Treatment

Nonsurgical, nonpharmacologic intervention is the first-line treatment for UI. Drug therapy may be considered in patients whose UI is not adequately controlled by nonpharmacologic therapies and in those who have no major contraindications to drug treatment. In general, pharmacotherapy provides better response when combined with nonpharmacologic interventions. Selection of agent should be based on the type of UI, and patient characteristics (e.g., age, comorbidities, concurrent drug therapies, ability to maintain medication adherence). Surgery can be considered when the degree of bother or lifestyle compromise is sufficient and other nonsurgical interventions are undesired or ineffective.

Antimuscarinic agents have been the mainstay of pharmacotherapy for OAB and UUI. According to American Urological Association (AUA) guideline, clinicians should avoid antimuscarinic agents in patients with narrow-angle glaucoma unless approved by the treating ophthalmologist. Antimuscarinic agents should be cautiously used in patients with fraility, impaired gastric emptying or a history of urinary retention, or in those who are taking other drugs with anticholinergic properties. When one agent offers inadequate symptom control and/or unacceptable adverse drug events, consider a dose modification or switching to another agent. Before abandoning effective antimuscarinic therapy, clinicians should manage constipation and dry mouth (bowel regimen, fluid management, dose modification or alternative antimuscarinics).23

Nonpharmacologic Therapy

Nonsurgical Treatment

![]() Nonpharmacologic, nonsurgical treatment of UI is recommended as the first-line therapy at a primary care level. It is the only option for patients in whom pharmacologic and/or surgical management is inappropriate or undesired. Examples of patients who fulfill these criteria for nonpharmacologic treatment include those who with mild to moderate symptoms who do not want to take medication; those with comorbid conditions that place them at high risk for adverse effects from drug therapy; those who are not medically fit for surgery; those who plan future pregnancies (which may adversely affect long-term surgical outcomes); those with overflow incontinence whose condition is not amenable to surgery or drug therapy; and those who are delaying surgery or do not want to undergo surgery.24,25

Nonpharmacologic, nonsurgical treatment of UI is recommended as the first-line therapy at a primary care level. It is the only option for patients in whom pharmacologic and/or surgical management is inappropriate or undesired. Examples of patients who fulfill these criteria for nonpharmacologic treatment include those who with mild to moderate symptoms who do not want to take medication; those with comorbid conditions that place them at high risk for adverse effects from drug therapy; those who are not medically fit for surgery; those who plan future pregnancies (which may adversely affect long-term surgical outcomes); those with overflow incontinence whose condition is not amenable to surgery or drug therapy; and those who are delaying surgery or do not want to undergo surgery.24,25

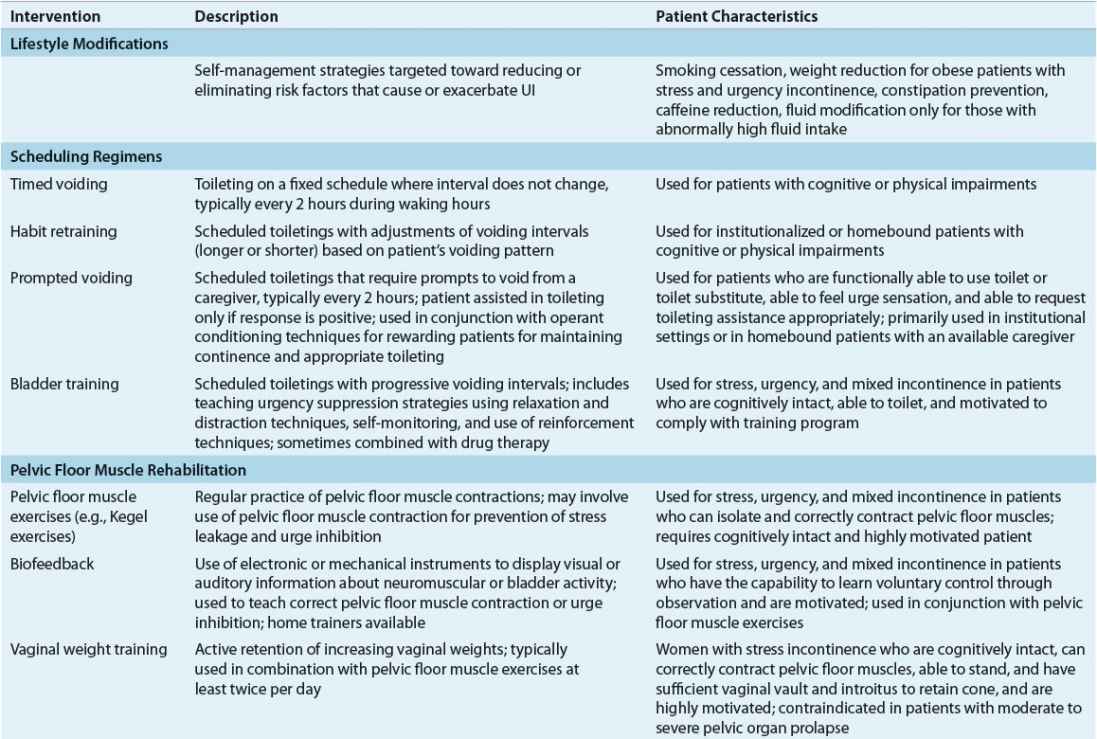

Nondrug interventions for UI include behavioral interventions, external neuromodulation, alternative medicine therapy, antiincontinence devices, and supportive interventions (Table 68-3).24,25 Behavioral interventions are generally the first-line of treatment for SUI, UUI, and mixed UI. Interventions include lifestyle modifications, toilet scheduling regimens, and pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation. Because the key to success with any type of behavioral intervention is motivation of patients or caregivers, these individuals must be active participants in developing a treatment plan. Regular follow-up is needed to help motivate patients and caregivers, provide reassurance and support, and monitor treatment outcomes.

TABLE 68-3 Nonpharmacologic Management of Urinary Incontinence

External neuromodulation may include nonimplantable electrical stimulation, percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation, or extracorporeal magnetic stimulation. This treatment option is typically prescribed when traditional pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation has failed. Antiincontinence devices such bed alarms, catheters, pessaries, and penile clamps and external collection devices are reserved for special situations depending on patients’ UI symptoms, cognitive and mobility status, and overall health status. Supportive interventions such as physical therapy may be beneficial for patients with muscle weakness and slow gait to reach the toilet in a timelier manner, and absorbent products will provide greater confidence in dealing with unpredictable urine loss.

Surgical Treatment

Only rarely does surgery play a role in the initial management of UI.26 In the absence of secondary complications from UI (e.g., skin breakdown or infection), the decision to surgically treat symptomatic UI should be based on the premise that the degree of bother or lifestyle compromise to the patient is great enough to warrant an elective operation, and that nonsurgical therapy either is undesired or has been ineffective.

Successful application of surgery depends mostly on defining the underlying abnormalities responsible for UI (bladder vs. urethra, underactivity vs. overactivity). Once the underlying factors are determined, other considerations include renal function, sexual function, severity of leakage, history of abdominal or pelvic surgery, presence of concurrent abdominal or pelvic pathology requiring surgical correction, and finally the patient’s suitability for the procedure and willingness to accept the risks of surgery.

If patients with uncomplicated SUI become dissatisfied with the initial management approaches of pelvic floor exercises, medications, and/or behavioral modification, surgical treatment assumes the primary role.26

Surgical correction of female SUI (urethral underactivity) is directed toward either (a) repositioning the urethra and/or creating a backboard of support, or otherwise stabilizing the urethra and bladder neck in a well-supported retropubic (intraabdominal) position that is receptive to changes in intraabdominal pressure; or (b) improving the sealing mechanism and/or creating compression or otherwise augmenting the urethral resistance provided by the intrinsic sphincteric unit, with (i.e., sling) or without (i.e., periurethral injectable bulking agents) urethral and bladder neck support.

Bulking agents are injected into the urethra at the level of the urinary sphincter as an office-based procedure and are generally considered quite safe. However, their durability and efficacy are likely inferior to other options.27

Midurethral synthetic slings have become the most common approach to the treatment of SUI in women in the United States.28 These can be inserted as outpatient procedures that have shorter convalescence periods and allow faster return to usual activities compared with many of the older procedures. These procedures are generally felt to be highly durable and efficacious. However, safety concerns have been recently expressed regarding the implantation of surgical mesh in some patients, the implications of which are yet to be fully clarified.29

SUI in men is very rare in the absence of prior pelvic surgery, injury, or neurologic disease. When it occurs, SUI in men can be treated in a number of ways.30 Bulking agents can be injected periurethrally and submucosally into the region of the external urinary sphincter. This approach is less effective and far less durable than alternative surgical procedures, although it can be performed in the office setting without the need for general anesthesia.

The artificial urinary sphincter is generally considered to be the gold standard for treatment of male SUI.30 Placement of this manually operated silicone device has been associated with very high long-term success and satisfaction rates.31 Male slings placed through a perineal incision are a newer alternative to the artificial urinary sphincter. However, long-term efficacy and safety data are lacking.32

Most patients with UUI are managed nonsurgically with a combination of behavioral modification, pelvic floor exercises, and pharmacologic therapy. However, for patients refractory to such measures, invasive therapy can beneficial. Posterior tibial nerve stimulation is an office-based percutaneous treatment for UUI or OAB. Therapy consists of weekly 30-minute treatments with a needle placed posteriorly to the medial malleolus of the ankle for 3 months. Efficacy appears similar to or slightly better than oral pharmacotherapy.33 However, long-term efficacy and safety data are lacking.34

Surgery for the treatment of UUI generally consists of implantation of a sacral nerve stimulator (neuromodulation) or endoscopic office-based injection of botulinum toxin directly into the detrusor muscle.35,36 Neuromodulation is a staged surgical procedure in which a neurostimulator lead is placed transforaminally at the level of sacral spinal cord root S3. Its exact mechanism is unknown, but the device may exert its favorable effects on urination and UUI by rebalancing the afferent and efferent nerve impulses to the lower urinary tract and pelvic floor. The injection of botulinum toxin is performed in the office generally with local anesthesia. The toxin is taken up by the efferent nerve terminals and prevents the release of acetylcholine into the synapse at the neuromuscular junction, thus inducing paralysis of the affected detrusor muscle. The duration of effect of the toxin is about 4 to 8 months, after which repeat injection is necessary to maintain effect. The therapeutic algorithm involving these two choices for treatment of refractory UUI is evolving and is determined largely by patient preference.37

Few surgical treatments for bladder underactivity are effective. After an appropriate evaluation for reversible causes, the most effective management of this condition is intermittent self-catheterization performed by the patient or a caregiver three or four times per day. Sacral nerve stimulation (neuromodulation) has shown some efficacy in this patient population, but success rates for detrusor underactivity (nonobstructive urinary retention) are inferior to those seen with urinary frequency and urgency.38 Proper patient selection for this therapy remains poorly defined. Alternative methods of management that are less satisfactory or more invasive include indwelling urethral or suprapubic catheters and urinary diversion.

Urethral overactivity is most commonly caused by anatomic obstruction. Anatomic obstruction in men is most often caused by benign prostatic enlargement. Treatments may include transurethral surgical resection of the prostate (see Chap. 67).

Rarely, bladder outlet obstruction is caused by a functional obstruction at the level of the bladder neck or external sphincter. Hypertrophy of the smooth muscle fibers at the level of the bladder neck in men and women may result in obstruction to the flow of urine. In patients who do not respond to pharmacologic therapy with α-adrenergic receptor antagonists, endoscopic incision using the cystoscope is highly effective in treating this very uncommon condition.

Pharmacologic Therapy

Urge Urinary Incontinence

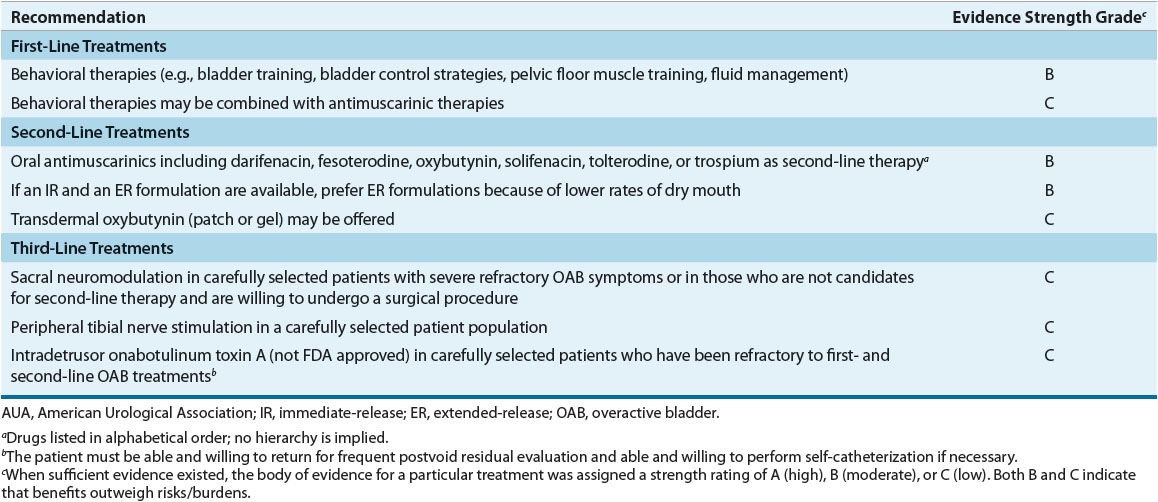

![]() Anticholinergic/antimuscarinic agents are the first-line drug therapy for relieving UUI symptoms and preventing its complications. Table 68-4 summarizes AUA recommendations for treating OAB in adults.23 Mirabegron, a β3-adrenergic agonist, was approved in 2012 for OAB or UUI. While the guideline does not discuss its role in comparison to other existing drug options, it may be considered as first-line therapy or in patients who do not adequately respond to or cannot tolerate anticholinergic/antimuscarinic drugs. Table 68-5 lists the usual dosage for approved agents for OAB or UUI. Table 68-6 suggests common monitoring parameters for these agents.

Anticholinergic/antimuscarinic agents are the first-line drug therapy for relieving UUI symptoms and preventing its complications. Table 68-4 summarizes AUA recommendations for treating OAB in adults.23 Mirabegron, a β3-adrenergic agonist, was approved in 2012 for OAB or UUI. While the guideline does not discuss its role in comparison to other existing drug options, it may be considered as first-line therapy or in patients who do not adequately respond to or cannot tolerate anticholinergic/antimuscarinic drugs. Table 68-5 lists the usual dosage for approved agents for OAB or UUI. Table 68-6 suggests common monitoring parameters for these agents.

TABLE 68-4 AUA Guideline for Treatment of Overactive Bladder in Adults