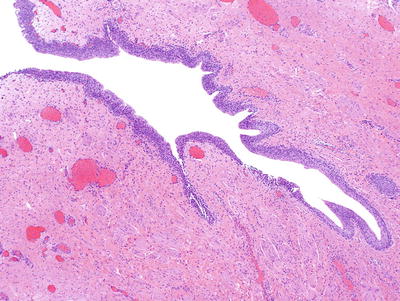

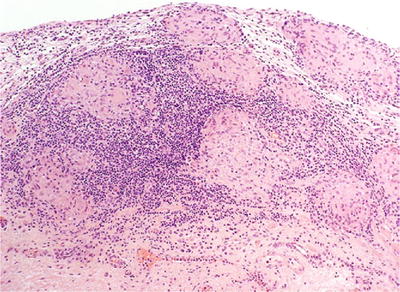

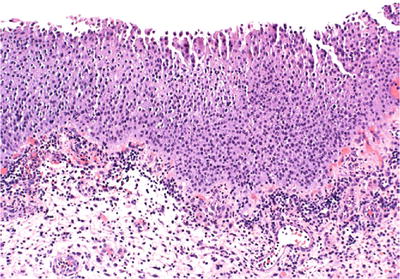

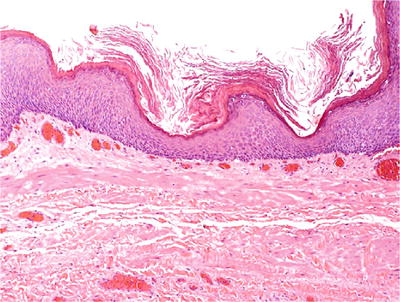

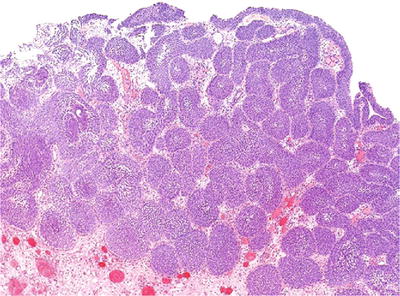

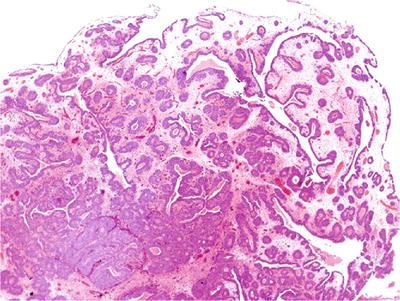

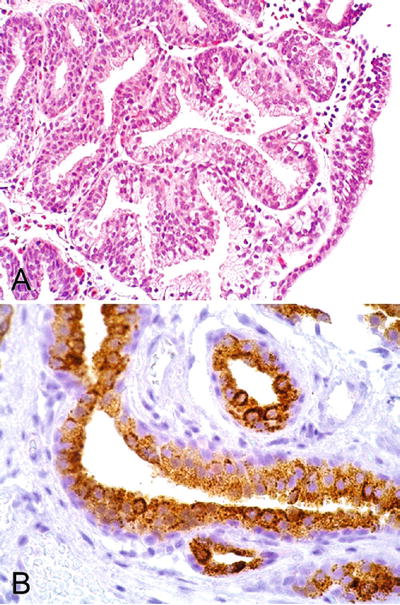

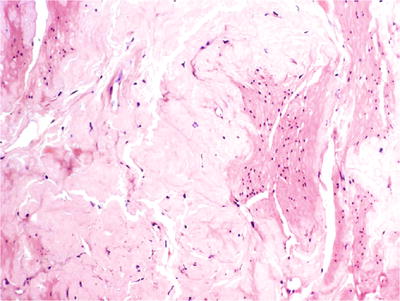

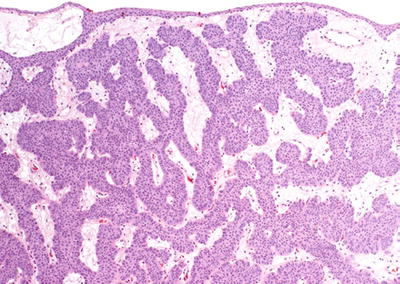

Fig. 36.1.

Exstrophy of the bladder. Extensive intestinal metaplasia is present.

Cystitis

♦

Cystitis is a descriptive and often nonspecific term that refers to a variety of benign inflammatory lesions

♦

May be associated with proliferative and metaplastic conditions

Acute Cystitis

♦

Acute cystitis is characterized by predominantly neutrophilic infiltration of the lamina propria and urothelium

♦

It is associated with edema of lamina propria and frequent urothelial denudation

♦

A number of clinicopathological variants have been described

Variants

♦

Ulcerative cystitis

The urothelium is denuded a nd ulcerated

♦

Suppurative membranous cystitis

The surface urothelium is covered by exudate and necrotic debris

♦

Emphysematous cystitis

Inflammatory condition caused by infection of gas-forming bacteria such as Clostridium perfringens

Usually limited to patients with predispositions to unusual infections including diabetes, neurogenic bladder, and chronic urinary tract infection

Gas-filled blebs with giant cell reaction in the lamina propria represent the main histologic finding

♦

Viral cystitis

Adenovirus, herpes simplex type II virus, a nd polyoma (Fig. 36.2) viruses have been implicated

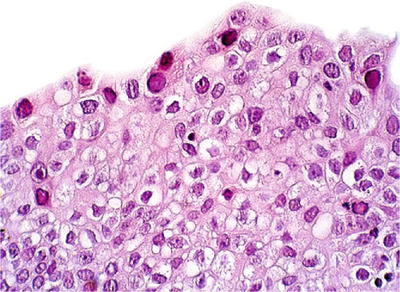

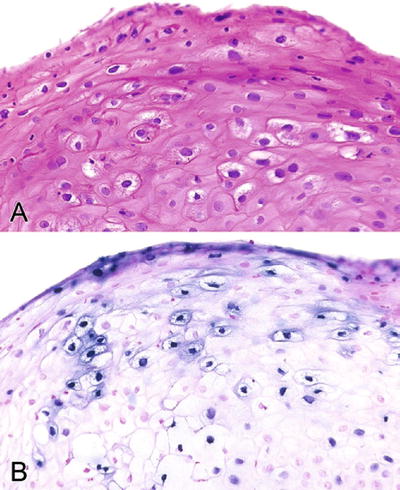

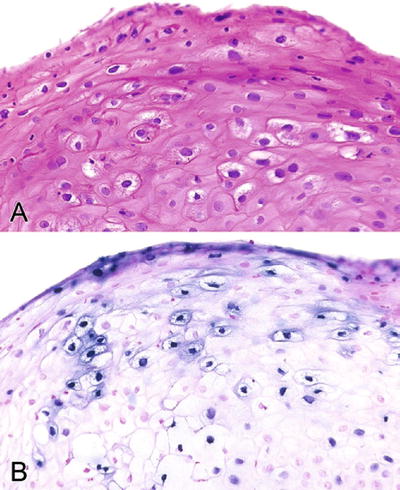

Fig. 36.2.

Polyoma virus infection . Nuclear viral inclusions are noted.

Patients with bladder involvement are usually immunosuppressed renal or bone marrow allograft recipients

May be associated with hemorrhagic cystitis

The identification of viral inclusions in histologic tissue sections is diagnostic

Herpes zoster and cytomegalovirus have been rarely implicated

No specific gross features have been described

♦

Fungal cystitis

Candida albicans, Torulopsis glabrata, Aspergillus fumigatus, and Coccidioides immitis have been implicated

Main clinical presentations are urinary tract irritative symptoms including nocturia, pain, and urgency and frequency

Grossly, the bladder mucosa is slightly elevated and irregular with white plaques

Ulceration and submucosal mixe d inflammation are frequently seen

Typical fungal spores and hyphae are present within fibrinopurulent debris

♦

Actinomycosis

A rare, localized mass simulating a tumor may be present

The submucosa and muscularis propria contain abundant granulation tissue and numerous abscesses

“Sulfur granules” consisting of masses of filamentous mycelia with a peripheral array of swollen eosinophilic “clubs”

Chronic Cystitis

♦

Chronic inflammatory infiltrate of lamina propria is the chief characteristic together with edema and fibrosis of the lamina propria

♦

A number of variants have been described

Variants

♦

Papillary–polypoid cystitis (proliferative papillary cystitis )

Occurs in patients with history of indwelling catheter or vesical fistula

Mainly seen in the dome or posterior wall of the urinary bladder

Characterized by broad papillary projections of inflamed lamina propria with overlying hyperplastic urothelium

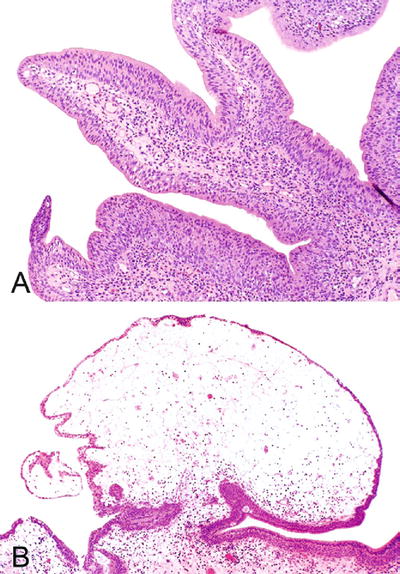

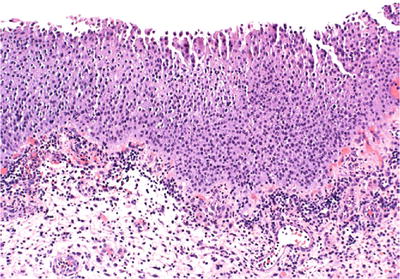

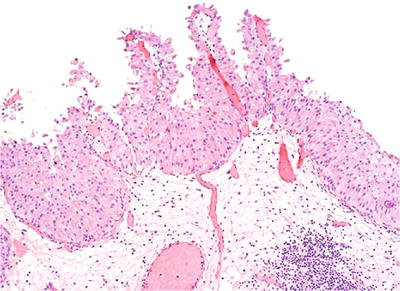

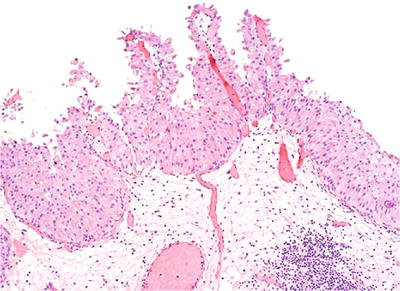

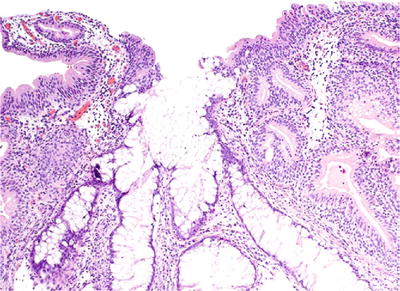

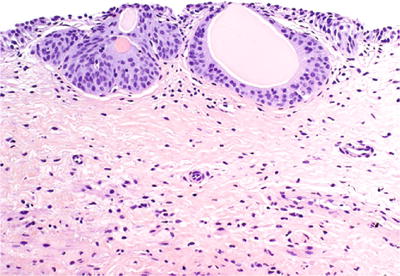

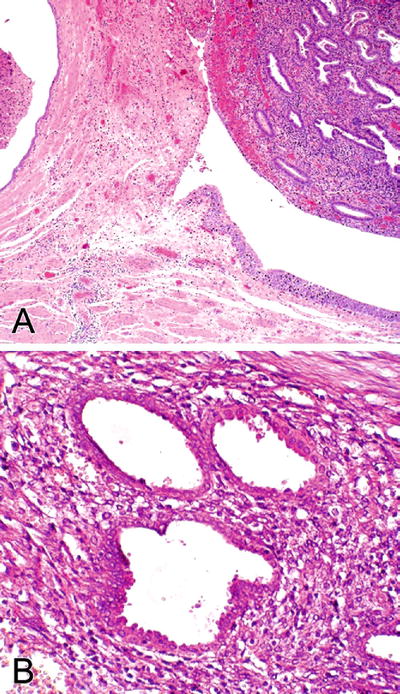

The designation papillary cystitis is used when thin, fingerlike papillae are present (Fig. 36.3A)

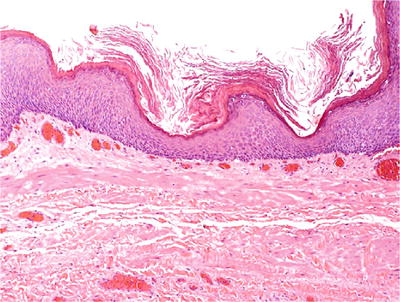

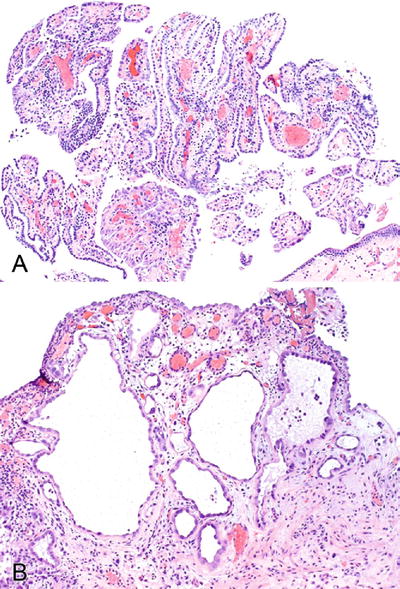

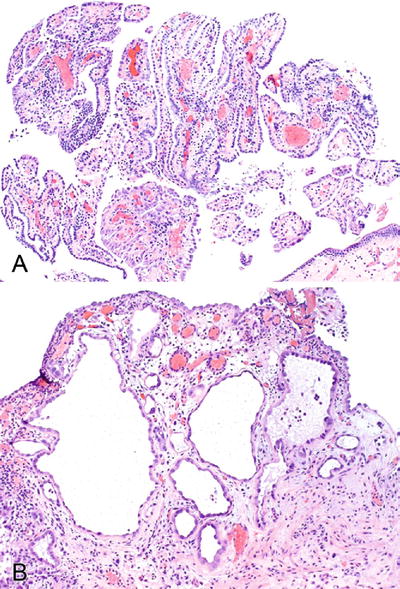

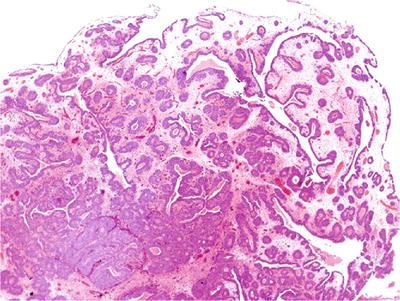

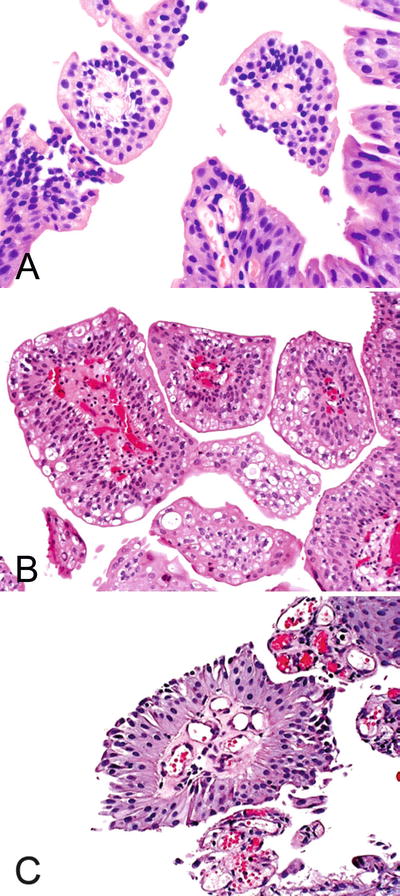

Fig. 36.3.

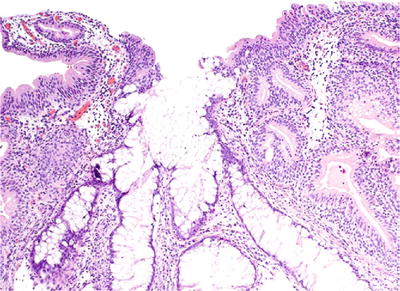

Proliferative papillary cystitis . (A) Papillary cystitis. (B) Polypoid cystitis.

Polypoid cystitis refers to lesions with edematous and broad-based papillae (Fig. 36.3B)

Superficial umbrella cells are invariably present

There is a prominent stromal edema, congestion, and inflammatory infiltrate

See further discussion in section “Benign Lesions and Mimics of Cancer”

♦

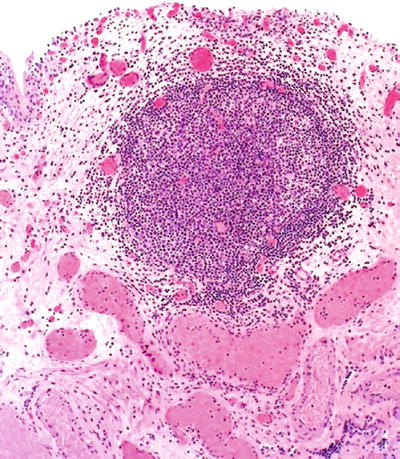

F ollicular cystitis

Typically an incidental finding

May be associated with history of infection, biopsy, or intravesical Bacillus Calmette–Guerin (BCG) therapy

Bladder mucosa may appear normal or have a finely nodular appearance cystoscopically

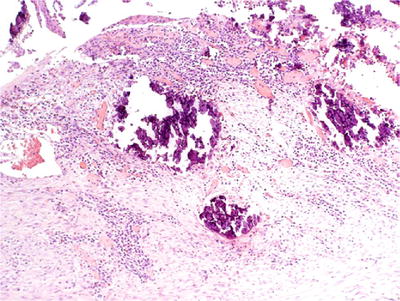

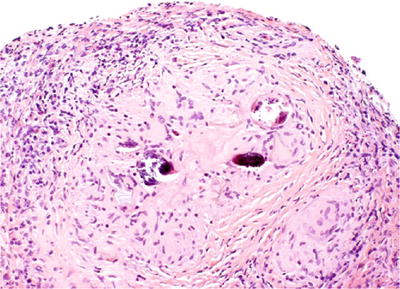

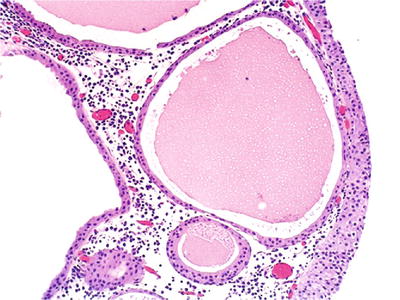

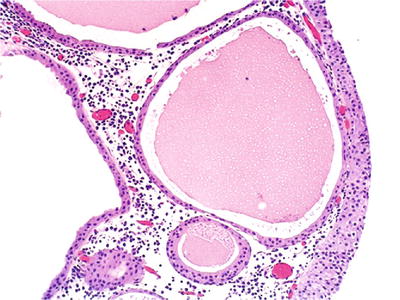

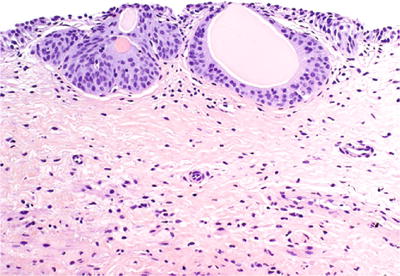

Subepithelial lymphoid follicles with germinal centers are seen (Fig. 36.4)

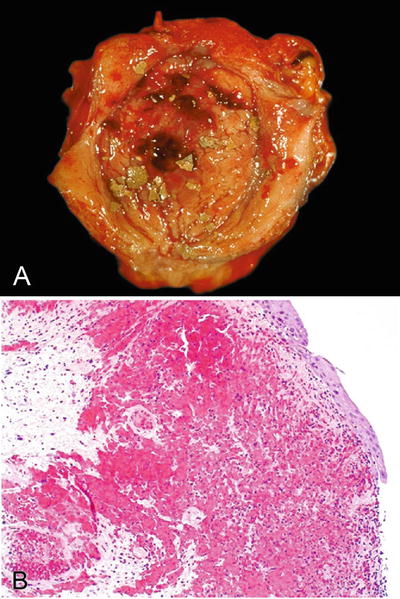

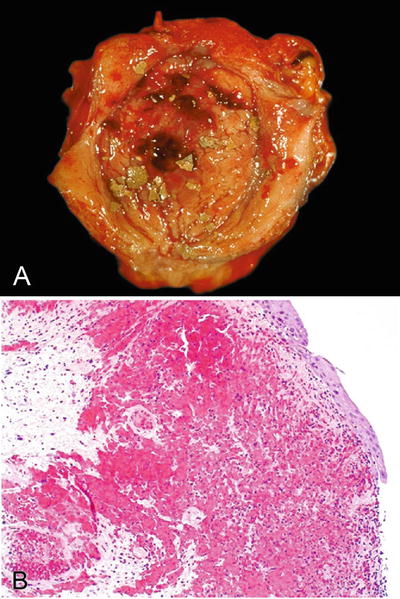

Fig. 36.4.

Follicular cystitis .

♦

Encrusted cystitis

Associated with infection of urea-splitting bacteria in alkalinized urine

The ulcers are coated with calcium and phosphate salt, mononuclear cell infiltrate, and foreign body giant cell reaction (Fig. 36.5)

Fig. 36.5.

Encrusted cystitis.

May rarely extend into the muscularis propria

Granulomatous Cystitis

♦

Etiology

Bacterial

•

Tuberculosis

•

Syphilis

Fungal

•

Coccidioidomycosis

•

Histoplasmosis

Parasitic

•

Schistosoma haematobium

Iatrogenic

•

Post surgery or radiation

•

Post intravesical (BCG) therapy

Malakoplakia

Systemic granulomatous disease

•

Crohn disease

•

Sarcoidosis

•

Rheumatoid disease

Chronic granulomatous disease of childhood

Xanthoma (with elevated serum cholesterol)

Vasculitis

•

Wegener granulomatosis

•

Polyarteritis nodosa

•

Churg–Strauss syndrome

Most cases remain idiopathic

Tuberculous Cystitis

♦

Is secondary to generalized spread from pulmonary infection by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and is often associated with renal tuberculosis

♦

Complications include scarring, obstruction, and fistula formation

♦

Histologically, presents as solitary or confluent ulcerated mucosal lesions, usually in the region of the ureteral orifices (trigone), with caseating granulomatous inflammation and fibrosis involving the lamina propria

♦

Frequently associated with the ulceration of the overlying mucosa

♦

Special stains (auramine–rhodamine or other AFB stain) demonstrate acid-fast bacilli

Malakoplakia

Clinical

♦

“Malakoplakia” means “soft plaque” in Greek

♦

This benign process was first described by Michaelis and Gutmann and by von Hansemann in 1902 and 1903

♦

There is a female predilection, with peak incidence in the fifth decade

♦

Patients typically present with symptoms of urinary tract infection

♦

Represents an atypical infection by bacteria (usually Gram bacteria, such as E. coli) in patients with lysosomal defects (defects in histiocyte function with impaired lysosome movement and inability of phagosomes to destroy bacteria)

♦

Symptoms include recurrent fever, hematuria, pyuria, urgency, pain, and weight loss

♦

Others organs may be involved

Macroscopic

♦

Multiple small yellow mucosal nodules or plaques, usually in the area of the trigone with a yellow to yellow-brown discoloration, not more than 2 cm in maximum dimension

Microscopic

♦

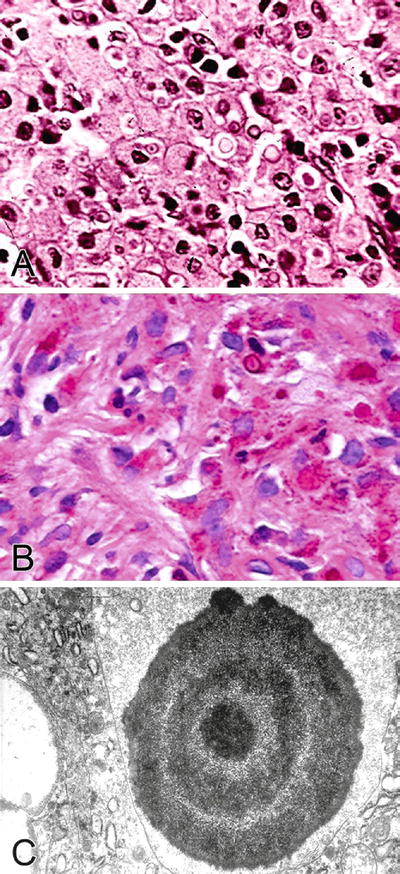

The lesion is characterized by mixed inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria

♦

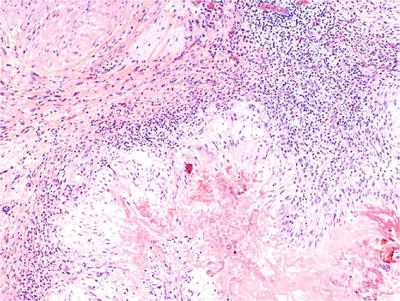

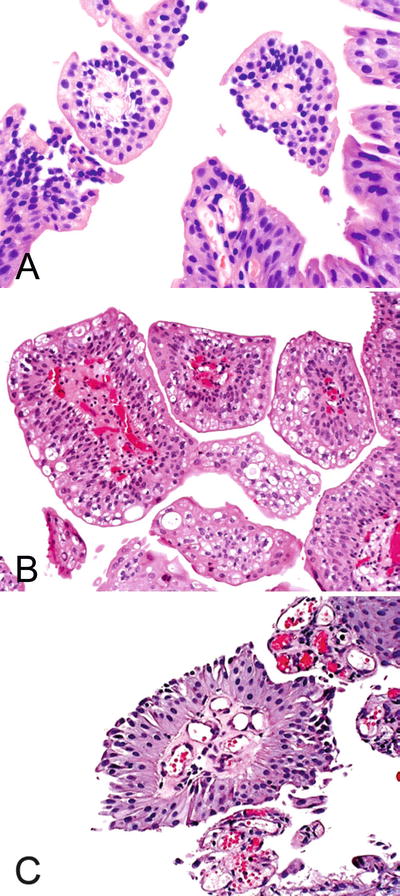

Large numbers of epithelioid histiocytes (von Hansemann histiocytes) with abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm and intracytoplasmic inclusions (Michaelis–Gutmann bodies, 3–10 μm) are present (Fig. 36.6A)

Fig. 36.6.

Malakoplakia. (A) H&E staining. (B) PAS staining. (C) Electron microscopy.

♦

Michaelis–Gutmann bodies are concentrically laminated basophilic round to oval calcospherites and may be PAS+, iron+, and calcium (von Kossa stain)+, either freely in the stroma or as intracytoplasmic inclusions (Fig. 36.6B)

Electron Microscopy

♦

Concentrically laminated structures with a central electron dense core and radially oriented spicules hydroxyapatite crystals (Fig. 36.6C)

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Adenocarcinomas, including signet ring cell adenocarcinoma

Significant cytologic atypia is present

Cytokeratin positive

Usually lacks prominent mixed inflammatory backgroun d

Schistosomiasis

Clinical

♦

Endemic in some parts of Africa and Southwest Asian countries, especially Egypt

♦

Granulomatous inflammation and fibrosis of lamina propria or muscularis propria

♦

Identification of schistosomal eggs (100 μm), frequently calcified in the bladder wall, is diagnostic (Fig. 36.7)

Fig. 36.7.

Schistosomiasis-associated granulomatous cystitis.

Treatment-Induced Cystitis

Radiation Cystitis

Clinical

♦

Inflammatory condition (with acute and chronic phases) associated with pelvic radiation treatment

♦

Patients have a previous history of radiation, not necessarily for bladder cancer, sometimes for prostate or cervical cancer

♦

Highly dose dependent (50% risk if receiving 70 Gy but only 5% risk with 60 Gy)

♦

Cystoscopy may show small papillary lesions, slight mucosal irregularities, or nonspecific findings

Microscopic

♦

Early changes appear after 3–6 weeks and include acute cystitis and desquamation of the urothelial cells associated with hyperemia

♦

Later, there is epithelial hyperplasia producing a pseudoinfiltrative appearance

Nests of urothelial cells may have jagged or irregular contours

♦

Budding off single cells may also be seen, and the nests may show squamous differentiation, raising the suspicion of a malignant process

♦

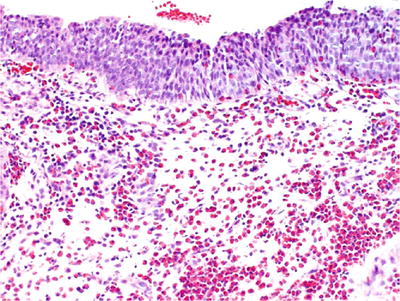

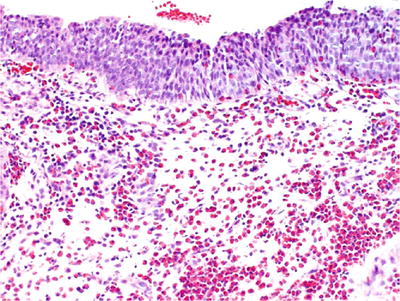

These cells show mild to severe cytologic atypia with nuclear hyperchromasia; however, nucleoli are inconspicuous, the nuclear-to-cytoplasmic (N/C) ratio is preserved or increased, and mitotic figures are typically absent—features that are not characteristic of a malignant process (Fig. 36.8A)

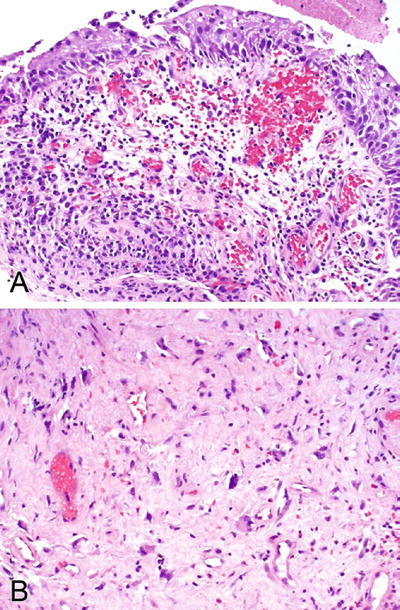

Fig. 36.8.

Radiation cystitis. (A) Acute phase and (B) chronic phase.

♦

Other helpful features are the finding of scattered enlarged fibroblasts (Fig. 36.8B) in the lamina propria associated with nuclear hyperchromasia, hemorrhage or fibrin deposition, edema, inflammatory cells, and ectatic vessels. Some vessels may show myointimal thickening and eccentric accumulation of amorphous pink material

♦

Acute phase occurs within 6 months (usually manifests within 6 weeks of treatment); subacute phase occurs from 6 months to 2 years after treatment; chronic phase usually takes 2–5 years to appear

Acute phase

•

H yperemia/congestion, petechiae

•

Marked edema with thick mucosal folds (“bullous cystitis”)

•

Mucosal erosion, denudation, and ulceration

•

Marked cellular atypia with large hyperchromatic, bizarre nuclei

•

Lamina propria edema and congestion

Subacute phase

•

Mucosal erythema, edema, and chronic inflammation

•

Mucosal ulceration, variable atrophy, and urothelial hyperplasia

Chroni c phase

•

Thin, atrophic mucosa with or without ulceration

•

Some degree of residual epithelial atypia

•

Urothelial metaplasia and hyperplasia

•

Fibrosis and collagen deposition in the lamina propria and muscularis propria with scattered atypical fibroblasts

•

Endothelial proliferation, arteriolar hyalinization, and subendothelial and medial fibrosis (endarteritis obliterans)

•

Fistula formation

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Main entity entering differential diagnosis is carcinoma in situ (CIS), which has high N/C ratio, nuclear pleomorphism, and hyperchromasia

BCG-Induced Granulomatous Cystitis

Clinical

♦

Clinical history is critical in determining the etiology of this increasingly frequent lesion

♦

BCG is used to treat patients with superficial high-grade bladder carcinoma or CIS

♦

Symptoms include dysuria, frequency, fever, and other systemic reactions (e.g., pneumonitis, hepatitis, rash, and arthralgia)

Microscopic

♦

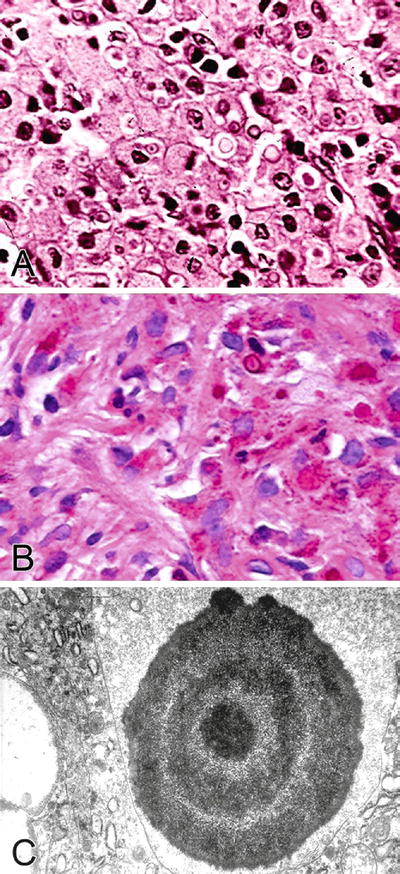

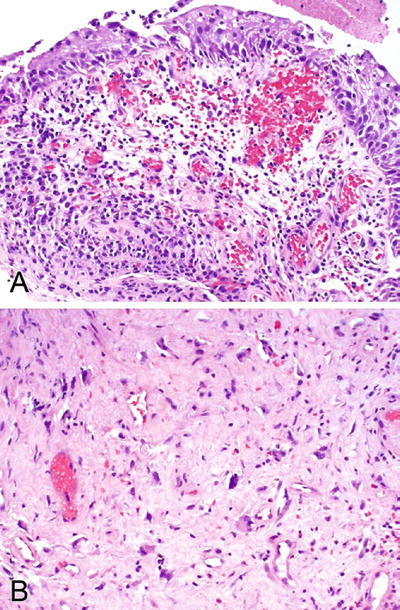

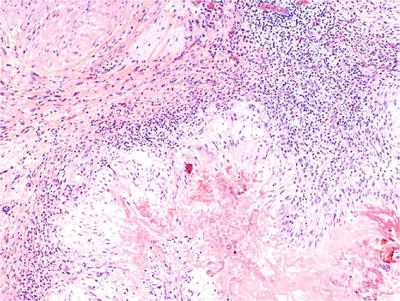

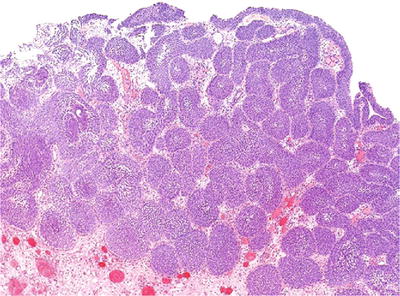

There is erosion and ulceration of the mucosa and a sarcoid-like nonnecrotizing granuloma with giant cells (Fig. 36.9)

Fig. 36.9.

BCG-treatment-associated granulomatous cystitis.

♦

Edema, congestion, and chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria are associated features

Cytoxan-Induced Hemorrhagic Cystitis

Clinical

♦

Occurs in up to 8% of patients treated with cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) and is secondary to toxic metabolite acrolein (an aldehyde and oxidizing agent from tobacco and systematic inflammation) that is excreted in the urine

♦

May result in severe, intractable hematuria, which may require cystectomy

Macroscopic

♦

At endoscopy, there is a diffuse, severe hyperemia with edema and erosion or ulceration of the mucosa (Fig. 36.10A)

Fig. 36.10.

Hemorrhagic cystitis. (A) Gross and (B) microscopic.

Microscopic

♦

Urothelial denudation/ulceration leads to regeneration with reparative urothelial changes that results in atypical urothelium covering a lamina propria with edema and extensive hemorrhage (Fig. 36.10B)

♦

A frequent finding is the activation of polyomavirus or adenovirus infection that should not be mistaken for malignancy

Postsurgical Granuloma

Clinical

♦

History of prior surgery or instrumentation.

♦

The etiology is related to immunologic recognition of altered antigen induced by the procedure (also known as necrobiotic granuloma)

Pathology

♦

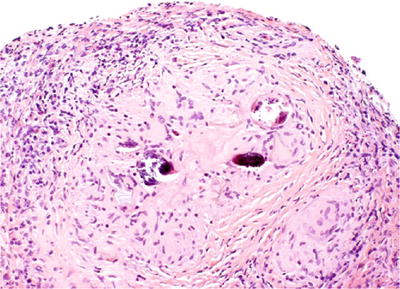

Hemorrhage, necrosis, and mucosal irregularities are common

♦

The granulomas include a central zone of fibrinoid necrosis surrounded by a peripheral rim of palisading epithelioid histiocytes (Fig. 36.11)

Fig. 36.11.

Postsurgical granuloma.

♦

Chronic inflammatory infiltrate composed of histiocytes, giant cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophil s

Special Variants of Cystitis

Interstitial Cystitis

Clinical

♦

Uncommon inflammatory process seen in middle-aged women (30–50 years) that presents with dysuria, urgency, frequency, hematuria, or generalized pelvic pain

♦

The diagnosis is made clinically based on symptoms and cystoscopic examination. There is also negative testing for bacterial, fungal, or viral pathogens

♦

Some cases are associated with allergic and autoimmune disorders (rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, or autoimmune thyroiditis)

♦

Antinuclear antigen test is positive in >50% of cases

Macroscopic

♦

Scattered petechial hemorrhages

♦

Wedge-shaped ulceration (Hunner ulcer)

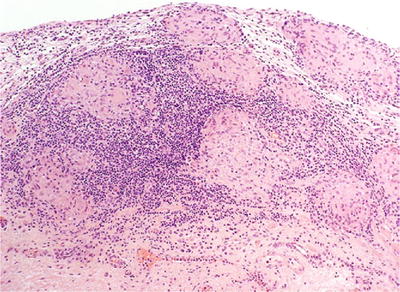

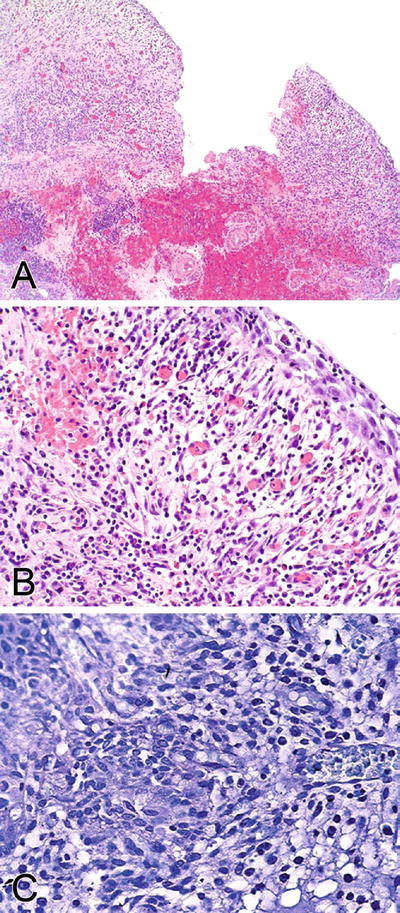

Microscopic (Fig. 36.12)

♦

There are two main histologic forms:

The ulcerated form (classic form; Hunner ulcer) shows scattered petechial hemorrhages and wedge-shaped ulcerations. The mucosa may be denuded or replaced by granulation tissue

The nonulcerated form shows edema and congestion, with a mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria. There are characteristic glomerulations (mucosal hemorrhage) and mucosal rupture

♦

Mast cell infiltration in the lamina propria and muscularis propria is common in both forms of interstitial cystitis

Perineural mononuclear infiltration is also common.

Fibrosis of the lamina propria and muscularis propria occurs frequently

Fig. 36.12.

Interstitial cystitis. (A) Hunner ulcer. (B) Nonulcer form. (C) Toluidine blue staining highlights mast cells.

Immunohistochemistry

♦

Discontinuous uroplakin III immunostaining in superficial (umbrella) cells of patients with interstitial cystitis and continuous immunostaining in urothelium of patients without disease has been reported

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Other forms of cystitis, including tuberculous cystitis and eosinophilic cystitis or nonspecific acute or chronic cystitis, should be considered in the differential diagnosis

Eosinophilic Cystitis

Clinical

♦

Inflammatory process found in women and children; seen with allergic disorders and other diseases associated with peripheral eosinophilia

♦

Uncommonly seen in elderly men with bladder injury or history of transurethral resection

♦

Symptoms include severe frequency, urgency, dysuria, and hematuria, with periods of remission and exacerbation

♦

Spontaneous resolution is common

Macroscopic

♦

Diffuse mucosal edema and erythema or velvety yellow plaque

♦

Tumorlike polypoid growths that appear erythematous and may demonstrate ulceration or necrosis

Microscopic

♦

Mononuclear and eosinophilic infiltrate in the lamina propria and muscularis is the main histological finding (Fig. 36.13)

Fig. 36.13.

Eosinophilic c ystitis.

♦

Early disease is characterized by marked edema, congestion, and a mixed mononuclear and eosinophilic infiltrate, but in severe cases, muscle necrosis may be seen

♦

As the disease progresses, the inflammatory infiltrate tends to subside, and varying degrees of fibrosis may be seen in the lamina propria and muscularis

Benign Lesions and Mimics of Cancer

Urothelial Hyperplasia

♦

Urothelial hyperplasia may be flat or papillary

Flat Urothelial Hyperplasia

♦

Flat urothelial hyperplasia is characterized by marked thickening of the mucosa usually to ten or more cell layers (Fig. 36.14)

Fig. 36.14.

Urothelial hyperplasia.

The nuclei may be slightly enlarged, but importantly, cytologic atypia is absent

There is morphologic evidence of maturation from basal cells to superficial cells

Mitotic figures are rare and limited to the basal layers

Tangential sectioning of suboptimally oriented biopsies may give a false impression of mucosal thickening

♦

The true incidence of flat hyperplasia is not known due to lack of large-scale screening studies

Flat urothelial hyperplasia may occur adjacent to low-grade papillary tumors or as an isolated lesion

When isolated, flat hyperplasia does not appear to have a premalignant potential

In contrast, frequent genetic alterations have been identified in flat hyperplasia and concurrent papillary tumors by loss of heterozygosity (LOH) analysis and FISH analyses

These studies suggest a link between flat hyperplasia and papillary urothelial carcinoma; but specific treatment is unwarranted in the absence of papillary urothelial carcinoma or CIS

Papillary Urothelial Hyperplasia

Clinical

♦

This is a controversial entity with unknown clinical significance.

♦

Some investigators consider it as a precursor to grade 1 papillary urothelial carcinoma.

♦

Most cases of papillary urothelial hyperplasia are discovered incidentally on followup cystoscopy for previous papillary tumors.

Microscopic

♦

The lesion displays undulating folds of urothelium that may have increased vascularity at the base of papillary folds, but lacks well-developed fibrovascular cores of a papillary neoplasm (Fig. 36.15).

Fig. 36.15.

Papillary urothelial hyperplasia.

♦

Although considered “hyperplastic,” papillary hyperplasia is typically surfaced by normal-appearing urothelium between four and seven cells in thickness.

♦

Cytologically, the urothelial cells in papillary hyperplasia lack atypia and maintain nuclear polarity.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

The primary differential diagnosis includes papilloma, low-grade papillary neoplasm, and papillary cystitis.

♦

In contrast to papillary neoplasms, papillary hyperplasia lacks arborization and detached papillary fronds.

♦

Papillary hyperplasia also lacks the broad-based stalks and inflammation seen in papillary–polypoid cystitis.

Metaplasia

Squamous Metaplasia

Clinical

♦

More commonly seen in men, with a male-to-female ratio (M:F) of 4:1.

♦

Usually occurs in the setting of longstanding chronic inflammation, but may be focally present in noninflamed bladders.

♦

Associated conditions include exstrophy, neurogenic bladder, indwelling catheter, previous surgery or biopsy, recurrent infection (e.g., schistosomiasis), and calculi.

♦

Nonkeratinizing squamous metaplasia of the trigone in women is a normal finding secondary to estrogen stimulation and does not need to be reported.

♦

Keratinizing squamous metaplasia is considered a putative precursor to carcinoma.

♦

Nonkeratinizing squamous metaplasia is not associated with increased risk of carcinoma.

Macroscopic

♦

May appear as multiple small nodular/papular mucosal lesions or as dull white plaques.

♦

Trigone is the region most commonly affected.

Microscopic

♦

It may appear as mature or immature keratinizing squamous epithelium (Fig. 36.16).

Fig. 36.16.

Keratinizing squamous cell metaplasia .

Nephrogenic Adenoma (Metaplasia)

Clinical

♦

Usually occurs in middle-aged men (M:F, 2:1; mean age, 41 years)

♦

In most cases, it is an incidental finding, but in one-third of cases, lesions are sizable and 10% are 4 cm or larger

♦

Frequently occurs in the setting of longstanding chronic irritation

♦

20% of cases occur in children and adolescents

♦

8% of patients have undergone kidney transplantation

In studies of these patients, the cells of nephrogenic adenoma derive from tubular cells of the renal transplant and are not metaplastic proliferations of the recipient’s bladder urothelium

♦

Approximately, 80% of the lesions occur in the bladder, with the remainder involving the urethra (15%) or ureter (5%) and, rarely, the renal pelvis

♦

Nephrogenic adenoma may recur, but malignant transformation has not been unequivocally documented

Macroscopic

♦

Papillary or polypoid small solitary yellow nodules (usually <1 cm)

♦

Erythematous irregular mucosa with a predilection for the trigone

Microscopic

♦

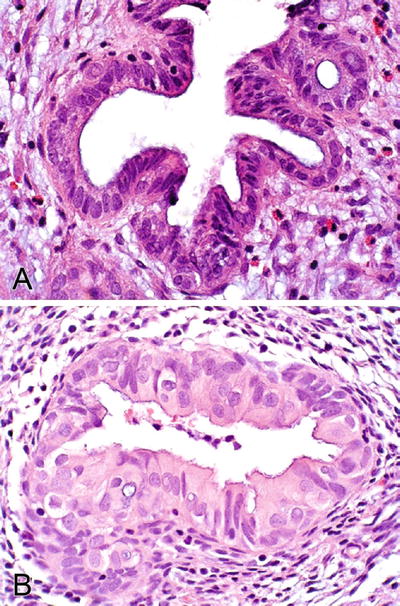

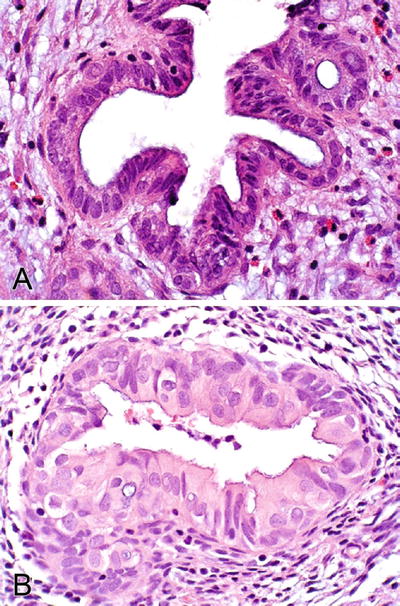

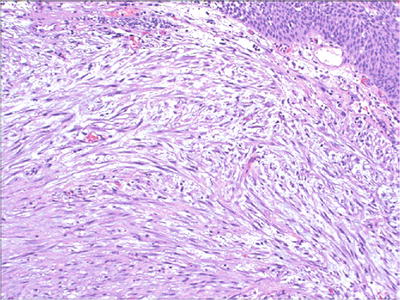

The lesion is composed of a well-circumscribed proliferation of small compact tubules, cysts, and delicate filiform papillae lined by columnar or cuboidal hobnail or flattened cells (Fig. 36.17)

Fig. 36.17.

Nephrogenic adenoma. Papillae and tubules are common patterns (A). Prominent nucleoli may be seen (B).

♦

Cells have clear to eosinophilic cytoplasm and uniform nuclei with inconspicuous mitotic figures

♦

Intracytoplasmic vacuoles (glycogen+) may be seen, imparting a signet ring cell appearance

♦

Tubules have thickened PAS+ basement membrane and may contain eosinophilic PAS+ secretions

♦

Often accompanied by chronic inflammation and associated with squamous metaplasia, cystitis cystica, and cystitis glandularis

♦

Cytologic atypia including nuclear enlargement, nuclear hyperchromasia, and enlarged nucleoli may be focally seen (atypical nephrogenic adenoma); however, these lesions are benign and do not need further treatment

♦

A rare variant of nephrogenic adenoma with myxoid stroma has been reported (fibromyxoid nephrogenic adenoma)

♦

The tubules of nephrogenic adenoma may occasionally be intermixed with muscle fibers of the muscularis mucosa in the bladder. This should not be mistaken for malignancy

Immunohistochemistry

♦

Strong positivity for wide-spectrum keratin, cytokeratin 7 (CK7), EMA, vimentin, PAX2, PAX8, and alpha-methylacyl-CoA racemase (P504S)

♦

p53 and Ki67 are typically negative

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Clear cell adenocarcinoma

Usually occurs in elderly women

The tumor is not confined to the lamina propria and has an infiltrative rather than well-circumscribed pattern of growth

Cytologic atypia and frequent mitotic figures are seen.

Immunohistochemical stains are not helpful in this differential diagnosis due to overlapping immunohistochemical profiles

♦

Urothelial c arcinoma with tubuloglandular pattern

Characterized by tubules lined by multiple layers of urothelial cells rather than a single-cell layer

Cytologic atypia, infiltrative growth, frequent mitotic figures, high proliferation (Ki67+), high p53 nuclear accumulation, lack of prominent basement membrane, and architectural heterogeneity favor malignancy

♦

Signet ring cell adenocarcinoma of the bladder or adenocarcinoma metastatic to the bladder

Significant cytologic atypia and single-cell infiltrates are seen

Vacuoles positive for mucin stains and negative for glycogen

Intestinal Metaplasia

♦

See discussion below on cystitis glandularis with intestinal metaplasia

Cystitis Glandularis

Clinical

♦

Cystitis glandularis is a relatively common histologic finding, most frequently seen in the trigone

♦

It can be divided into two subtypes: usual type and intestinal type (cystitis glandularis with intestinal metaplasia)

♦

Cystitis glandularis of the usual type is a common benign lesion

♦

Cystitis glandularis of the intestinal type (cystitis glandularis with intestinal metaplasia) is less frequent (incidence of 0.1–0.9%) and more commonly seen in patients with exstrophy and pelvic lipomatosis

Cystitis glandularis with intestinal metaplasia has been considered a premalignant lesion by some investigators.

A recent molecular study indicates that intestinal metaplasia in the urinary bladder is associated with significant telomere shortening relative to adjacent normal urothelial cells

These lesions also occasionally show cytogenetic abnormalities associated with telomere shortening

Macroscopic

♦

On cystoscopic examination, these lesions may be seen as a nodular or polypoid growth, especially for cases of cystitis glandularis of intestinal type; these may mimic a malignant neoplasm

Microscopic

♦

This lesion typically evolves and imperceptibly merges with von Brunn nests, a common benign epithelial abnormality of the bladder

♦

When those nests become cystic with central lumen formation and polarization of the inner cells, the term cystitis glandularis is used

♦

Cystitis glandularis, of the usual type, is composed of an inner layer of columnar to cuboidal cells surrounded by an outer layer of transitional cells

Similar epithelium may be present on the surface.

♦

The glands of cystitis glandularis of the intestinal type are lined by mucinous epithelium including goblet cells, closely resembling colonic epithelium (Fig. 36.18)

Fig. 36.18.

Cystitis glandularis w ith intestinal metaplasia.

It may be florid and associated with mucin extravasation

The stroma may show mild edema or hyalinization and inflammatory cell infiltration

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Primary bladder adenocarcinoma

The distinction between these two entities is based on growth pattern and cytology

Adenocarcinoma often presents as advanced-stage cancer with the bulk of the tumor in the serosa and muscularis propria and with less involvement of the lamina propria. The degree of cytologic atypia is substantial

In contrast, the benign process (cystitis glandularis with intestinal metaplasia) is characterized by an orderly distribution of glands lacking cytologic atypia or mucinous cells freely floating in mucinous pools

♦

Endocervicosis

This is a benign müllerian lesion composed of glands lined by endocervical-type epithelium, some of which may rupture resulting in mucin extravasation. However, if the latter is present, it is very focal and associated with a histiocytic and fibroblastic inflammatory response

Endocervicosis is often centered in the muscularis propria rather than the lamina propria

Cystitis Cystica

♦

May appear as small (1–5 μm) yellow cysts in the lamina propria

♦

These are unilocular cysts lined by single or multiple layers of cuboidal urothelial cells (Fig. 36.19)

Fig. 36.19.

Cystitis cystica.

♦

Acute and chronic inflammation may be present

von Brunn Nests and von Brunn Nest Proliferations

♦

Occur in ~85% of autopsy patients. Represent a normal variant of bladder mucosa

♦

Solid nests of urothelium project into the lamina propria; may contain luminal eosinophilic secretions (Fig. 36.20)

Fig. 36.20.

von Brunn nest.

♦

Exuberant von Brunn nest proliferation may be observed, mimicking inverted papilloma or inverted urothelial carcinoma (Fig. 36.21)

Fig. 36.21.

Exuberant von Brunn nest proliferation.

Florid Cystitis Glandularis

Clinical

♦

Usually an incidental finding

♦

Patients may present with irritative obstructive symptoms or hematuria

♦

No malignant potential

Macroscopic

♦

Nodular or polypoid lesion, with predilection for the trigone and bladder neck

Microscopic

♦

There is involvement of von Brunn nests by glandular metaplasia resulting in an exuberant proliferation of glands lined by columnar cells, with or without goblet cells (Fig. 36.22)

Fig. 36.22.

Florid cystitis glandularis.

♦

Lesions are confined to the lamina propria and lack significant cytologic atypia, but some may be difficult to differentiate from adenocarcinoma

The situation may be further confounded by extravasation of mucin into the stroma

♦

Characterized by proliferations of glands in the lamina propria; some have the appearance of cystitis glandularis of the usual type

♦

Most glands are lined by tall columnar cells with basally located nuclei lacking cytologic atypia

♦

Paneth cells may be seen

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Adenocarcinoma is the main differential diagnosis and has significant cytologic atypia, infiltrative growth, and invasion into muscularis propria

♦

Endocervicosis and müllerianosis may involve both the muscularis propria and lamina propria, but the greater portion of the lesion is in the muscularis propria

Endometriosis

Clinical

♦

The bladder is the organ most commonly involved by endometriosis in the urinary tract

Approximately 1% of women with endometriosis have urinary bladder involvement

Typically occurs in women of reproductive age

Up to 50% have a history of pelvic surgery

Rarely, vesical endometriosis has been reported in men with prostate carcinoma treated by estrogen therapy

Clinical manifestations include frequency, dysuria, and hematuria, and in 75% of cases, these symptoms have catamenial exacerbations

♦

A suprapelvic mass is palpable in 50% of the patients

Secondary and significant complications include obstruction of the ureteric orifices with secondary hydronephrosis or vesicocolic fistula

Most commonly involves the posterior wall or trigone

Presents as a n elevated, congested, and edematous area in the mucosa overlying a translucent, blue–black, or red–brown area of discoloration

On rare occasion, the appearance may mimic cystitis glandularis or an unusual gross morphology of bladder cancer

Macroscopic

♦

On gross examination, it may form a mass involving the bladder wall, most often secondary to muscle hypertrophy or fibrosis associated with endometriosis

If there is no mass, a hemorrhagic punctate lesion may be observed if the glands are cystically dilated secondary to catamenial changes

Microscopic

♦

The lesion is composed of endometriotic glands, stroma, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages (requires two of these three elements to make the diagnosis)

♦

The e ndometrial glands are typically lined by cuboidal cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and pseudostratified nuclei that may show mitotic activity depending on the phase of the cycle

♦

The stroma may contain foamy histiocytes with some chronic inflammatory cells

♦

The endometriotic stroma may be focally absent around some of the glands, and in postmenopausal women that are not on estrogen replacement, the diagnosis of endometriosis may be made in the absence of endometrial stroma.

In such instances, the glands still retain their endometriotic appearance

In some cases, the endometrial stroma may be replaced by elastotic stroma similar to that seen in radial scars of the breast

♦

In the urinary bladder, malignant tumors have arisen in association with endometriosis, most commonly endometrioid and clear cell adenocarcinomas

Endocervicosis

Clinical

♦

Occurs in women of reproductive age who complain of suprapubic pain, dysuria, frequency, and hematuria with catamenial exacerbation of the symptoms

♦

Predilection for posterior wall or posterior dome

Microscopic

♦

Proliferation of endocervical-type glands, which are often cystically dilated and reactive, but lack significant cytologic atypia

♦

Usually involves the muscularis propria

♦

There is a haphazard proliferation of glands throughout the bladder wall, typically centered in the muscularis propria, which may extend to the lamina propria or bladder serosa; however, the glands do not show crowding or back to back growth

♦

The glands have irregular sizes and shapes and are lined by a single layer of columnar cells with abundant pale mucinous cytoplasm (mucicarmine and PASD positive). The cells have a basally located small nucleus as seen in normal endocervical glands

♦

Cells with a goblet-like appearance may be seen with the nucleus eccentrically compressed

♦

Some glands may contain ciliated cells or nonspecific cuboidal cells intercalated with the mucinous cells, and in some cases, occasional endometriotic glands may be seen (Fig. 36.23)

Fig. 36.23.

Endocervicosis (A, B).

♦

Cytologic atypia is absent or mild and mitotic activity is exceptionally rare

♦

Extravasated mucin is associated with stromal edema, fibrosis, and a prominent inflammatory response

♦

May be associated with endometriotic stroma

♦

Primary adenocarcinoma may develop in a background of endocervicosis, in which case, there is a transition from dysplastic epithelium to frankly malignant glands

Immunohistochemistry

♦

Immunohistochemical stains show apical positivity of the mucinous cells for CA125 (antigen present in normal müllerian epithelia including endocervical, endometrial, and tubal epithelium)

♦

Estrogen and progesterone receptors are positive

♦

PAX8, CEA, EMA, and cytokeratin are also positive

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Cystitis glandularis (intestinal type), urachal remnants, and primary or secondary adenocarcinoma enter the differential diagnosis

Müllerianosis

Clinical

♦

Occurs in women of reproductive age (37–46 years)

♦

Commonly located in the posterior wall of the bladder and may form a tumorlike mass (up to 3 cm)

Microscopic (Fig. 36.24)

♦

This entity is defined as a benign epithelial proliferation composed of an admixture of tubal, endocervical, and endometrioid-type müllerian glandular epithelium outside the primary müllerian system.

♦

Characterized by the presence of at least two of three components:

Endosalpingiosis

Endocervicosis

Endometriosis (triad of endometrial glands, stroma, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages)

♦

Müllerianosis typically involves the lamina propria and muscularis propria as a proliferation of tubules and cysts with irregular sizes and shapes lined by ciliated cells intercalated with peg cells, next to endometriotic glands with endometrial stroma, and a component of glands lined by columnar mucinous cells

♦

CD10+ cells in the stroma help to recognize endometriosis

Fig. 36.24.

M üllerianosis. (A) Two components of müllerianosis (endocervicosis and endometriosis) are seen. (B) Endometriosis.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

The differential diagnosis includes cystitis glandularis, cystitis cystica, and nephrogenic adenoma

Cystitis glandularis does not involve the muscularis propria, the glands are lined by the urothelium, and endometriotic stroma is not seen

Müllerianosis typically involves the muscularis propria and lamina propria of the posterior wall

Nephrogenic adenoma typically shows a tubulocystic pattern. Cilia or mucinous cells are not present. Nephrogenic adenoma does not involve the muscularis propria

Diverticulosis

Clinical

♦

Acquired outpouching of the mucosa through the muscularis propria, usually due to increased pressure associated with bladder outlet obstruction (most commonly prostatic hyperplasia)

♦

Usually occurs in elderly male patients

♦

The diverticulum may give rise to calculi or tumor

♦

Tumors developing from diverticulosis are usually urothelial carcinoma, but adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or carcinosarcoma may be seen

Macroscopic

♦

Pockets of bladder mucosa projecting into (and sometimes through) the muscularis propria

♦

Usually located in the posterior wall, the dome, and the region of the urachus

♦

May contain calculi

Microscopic

♦

The lining is usually urothelial

♦

Varying degrees of inf lammation are seen

Postoperative Spindle Cell Nodule

Clinical

♦

Rare sequela of bladder or prostate surgery, especially transurethral resection

Usually presents weeks to months after surgery

♦

May be an incidental finding during routine followup or patients may present with microscopic hematuria, urinary obstruction, or irritative voiding

♦

On cystoscopy, the lesions are typically polypoid or nodular with poorly defined margins

♦

These lesions may destroy and infiltrate the bladder wall mimicking a malignant tumor

♦

They have a benign clinical course and conservative treatment is recommended.

Macroscopic

♦

Soft or firm small submucosal lesion with a gray, yellow, to tan cut surface

♦

Polypoid or nodular growth, typically in the same area as the previous surgery

Microscopic

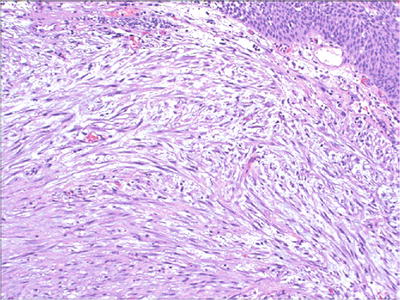

♦

Cellular spindle cell neoplasm with loosely arranged intersecting fascicles and myxoid vascular stroma.

♦

Tumor cells have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. The nuclei are oval or spindled throughout the lesion, with one or two small nucleoli and delicate chromatin.

♦

Mitotic activity may be brisk, up to 25/10 hpf; however, no atypical mitosis or significant cytologic atypia is seen (Fig. 36.26).

Fig. 36.26.

Postoperative spindle cell nodule.

♦

The tumor edge may have a pseudoinfiltrative appearance.

♦

The spindle cells are admixed with a variable number of chronic inflammatory cells in the deeper areas of the lesion, while the superficial component may be associated with acute inflammatory infiltrate due to surface ulceration.

♦

Areas of edema, myxoid change, and multiple small foci of hemorrhage are typically seen.

♦

The cells of the postoperative spindle cell nodule are myofibroblasts by ultrastructure examination and by immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry

♦

Cytokeratin and vimentin negative; smooth muscle actin often positive

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Sarcoma (leiomyosarcoma, fibrosarcoma)

Sarcoma will show compact, dense cellularity as well as cytologic atypia, atypical mitotic figures, and tumor necrosis

Clinical history of bladder surgery or procedures within the last 6–8 weeks is helpful in establishing the diagnosis

♦

Sarcomatoid carcinoma (especially myxoid variant)

Biphasic tumor with identifiable epithelial elements (cytokeratin+)

Cytologic atypia is present

♦

Kaposi sarcoma

Spindle cell proliferation of malignant endothelial cells with cytologic atypia

Hemorrhage may results in rows or clusters of red cells within slit-like spaces associated with hemosiderin-laden macrophages and chronic inflammatory cells

CD31 and/or CD34 immunostains are positive

♦

Inflammatory myofibroblasts tumor

Does not have a previous history of surgery at the site where it develops

ALK positive

Ectopic Prostatic Tissue

Clinical

♦

Occurs most frequently in adolescents or young adults but can also occur in older patients, ranging in age from 30 to 84 years old

♦

The etiology is uncertain

♦

Presents with hematuria or irritative symptoms

♦

Mainly seen in the bladder and prostatic urethra

Microscopic

♦

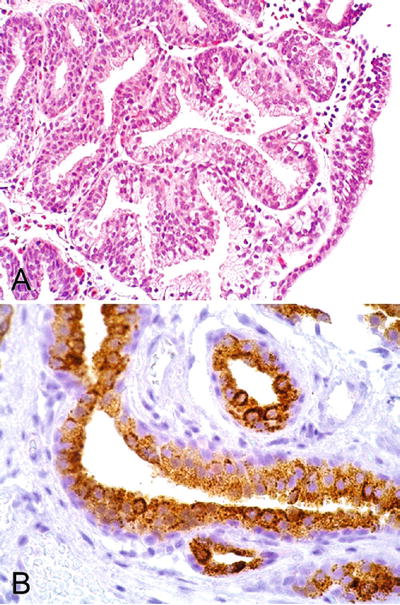

Benign prostatic glands with overlying intact urothelium (Fig. 36.27)

Fig. 36.27.

Ectopic prostatic tissue. (A) H&E. (B) PSA immunostaining.

Immunohistochemistry

♦

PSA, PSAP, and P501S are positive

♦

High-molecular-weight cytokeratin (34βE12) positive in basal cell s

Papillary–Polypoid Cystitis (Proliferative Cystitis)

Clinical

♦

Also discussed in section “Cystitis” (chronic cystitis)

♦

These lesions are the result of inflammation and edema in the lamina propria

They may be seen in up to 80% of patients with indwelling catheter

♦

Vesical fistulae, whether resulting from appendicitis, Crohn disease, diverticulitis, or colorectal cancer, are also frequently associated with proliferative cystitis

In about 50% of patients, however, obvious signs of extravesical disease may be initially absent

♦

On cystoscopy, the lesion frequently resembles papillary urothelial carcinoma

Macroscopic

♦

Most lesions are microscopic in size but, in up to 33%, may reach 5 mm in largest dimension

♦

Papillary structures may be recognizable

Microscopic

♦

The term “polypoid” is used for bulbous, broad-based lesions, and the term “papillary” is used for lesions with a fingerlike appearance

♦

Distinguishing polypoid–papillary cystitis from papillary urothelial carcinoma can be challenging

In contrast to papillary urothelial carcinoma, the fronds associated with proliferative cystitis are much broader and branching is absent or minimal (see Fig. 36.3)

♦

There is prominent edema associated with reactive and metaplastic changes such as squamous metaplasia

♦

The urothelium may be hyperplastic but it lacks cytologic atypia

Pyogenic Granuloma

♦

Rare examples of pyogenic granuloma have been described in the bladder

♦

The histology is similar to pyogenic granuloma seen at other organ sites

Condyloma Acuminatum

♦

Rarely occurs in the urinary bladder

♦

Usually coexists with condyloma of the urethra, vulva, vagina, anus, or perineum

♦

M:F, 1:2; occurs in all ages

♦

At cystoscopy, isolated or multiple exophytic lesions mainly in bladder neck or trigone

♦

Low-risk HPV DNA (type 6) has been found in some cases

♦

Morphology is identical to those seen in other organ sites; koilocytic atypia is present (Fig. 36.28)

Fig. 36.28.

Condyloma acuminatum. Koilocytic change can be subtle (A) and human papillomavirus in situ hybridization is positive (B).

Amyloidosis

Clinical

♦

Primary amyloidosis of the bladder is rare and has a male predominance

♦

May be confused clinically with urothelial carcinoma at initial presentation, as patients are typically in their sixth to eighth decade and have similar clinical symptoms

♦

On cystoscopic examination, raised, erythematous, papillary, and hemorrhagic lesions may be detected; some may be seen as yellow submucosal plaques; the lesions are often multiple

♦

Most commonly involved areas include the posterior and posterolateral walls and the trigone

♦

Local recurrences are common, but in most cases patients do not develop systemic amyloidosis; conservative treatment is recommended

Microscopic

♦

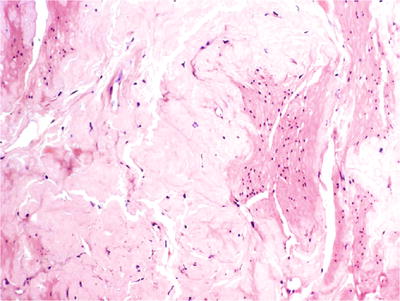

The muscularis mucosae and muscularis propria are infiltrated by extracellular proteinaceous amorphous eosinophilic deposits that may be accompanied by a minimal degree of chronic inflammation (Fig. 36.29)

Fig. 36.29.

Amyloidosis of the urinary bladder.

♦

Congo red stain allows visualization of the characteristic fluorescent apple green color under polarized ligh t

Neoplasms Of The Bladder (Table 36.1)

Table 36.1.

Classification of Urothelial Tumors

Urothelial tumors Urothelial papilloma (benign) Inverted papilloma (benign) Urothelial proliferation of uncertain malignant potential (formerly urothelial hyperplasia) Noninvasive papillary urothelial carcinoma Invasive urothelial carcinoma Variants Divergent differentiation (specify percentage) With squamous differentiation With glandular differentiation With trophoblastic differentiation Nested, including large nested Microcystic Micropapillary Lymphoepithelioma-like Plasmacytoid Sarcomatoid Clear cell (glycogen-rich) Lipoid cell (lipid-rich) Pleomorphic giant cell carcinoma Urothelial carcinoma with unusual stroma reactions With pseudosarcomatous stroma With stromal osseous or cartilaginous metaplasia |

Squamous neoplasms Squamous cell papilloma Squamous cell carcinoma Variants Verrucous squamous cell carcinoma Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma Schistosoma-associated squamous cell carcinoma |

Glandular neoplasms Villous adenoma Adenocarcinoma |

Tumor of müllerian type Clear cell carcinoma |

Neuroendocrine tumors Paraganglioma Carcinoid Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma Small cell carcinoma |

Sarcomatoid carcinoma |

Soft tissue tumors Leiomyoma Granular cell tumor Neurofibroma Hemangioma Solitary fibrous tumor Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) Rhabdomyosarcoma Leiomyosarcoma Angiosarcoma Osteosarcoma Others |

Benign Urothelial Neoplasms

Urothelial Papilloma

Clinical

♦

Most papillomas are solitary lesions, occurring in younger patients than carcinoma (mean age, 46 years; range, 22–89 years)

♦

Accounts for 1–2% of papillary urothelial neoplasms in some series

♦

Hematuria is the most common presenting symptom

♦

Urothelial papilloma may arise as a de novo neoplasm, or it may occur in patients with a clinical history of bladder cancer, as a secondary papilloma

♦

Urothelial papilloma may recur; however, it does not progress; aggressive behavior has been reported in a patient with urothelial papilloma on immunosuppressive therapy secondary to a renal transplant

♦

The cystoscopic appearance is identical to that of low-grade papillary neoplasms

Delicate, small papillary tumor that usually is solitary

Macroscopic

♦

Exophytic solitary small papillary lesion (<2 cm)

Microscopic

♦

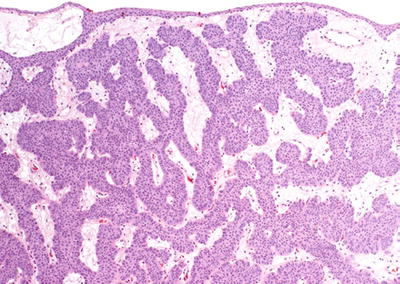

Urothelial papilloma is a benign exophytic neoplasm composed of a delicate fibrovascular cores lined by normal-appearing urothelium (Fig. 36.30)

Fig. 36.30.

Urothelial papilloma . (A–C) The fibrovascular cores with fewer than seven epithelial layers.

♦

Key features

Cytologically and architecturally normal urothelium covers delicate fibrovascular stalks

<7 layers in thickness

Normal polarity is retained

Mitoses are absent to rare and, if present, are located in the basal cell layer

Lacks cytologic atypia

Cytokeratin 20 (CK20) expression is identical to that in normal urothelium (superficial “umbrella” cells only)

♦

The superficial (umbrella) cells are often prominent and may display increased cytoplasm, vacuolization, and degenerative nuclear atypia

♦

The stroma may show edema and/or lymphoid inflammatory cells

♦

Rarely, urothelial papilloma shows extensive multifocal involvement of the mucosa; a phenomenon referred to as diffuse papillomatosi s

Molecular

♦

Papillomas are diploid and show frequent FGFR3 (75%) mutation

♦

A recent study found FGFR3 mutations in urothelial papilloma with a frequency comparable to that of papillary urothelial neoplasia of low malignant potential and low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma

Immunohistochemistry

♦

Papilloma shows low proliferation and uncommon p53 nuclear accumulation

♦

CK20 expression is limited to the superficial (umbrella) cells in the usual expression pattern for normal urothelium

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential and low-grade papillary carcinoma enter the differential diagnosis

♦

Tumors typically have longer slender papillae covered by urothelium with a variable degree of hyperplasia (>7 cell layers) and some degree of cytologic atypia.

♦

Urothelial papillomas show discrete papillary fronds with occasional branching but without fusion and are covered by normal urothelium .

Inverted Papilloma

Clinical

♦

Rare benign urothelial neoplasm that comprises less than 1% of urothelial tumors

♦

Presents with hematuria and irritative symptoms

♦

M:F, 4.5:1; age range, 10–94 years

♦

Some cases may be multifocal

♦

Inverted papilloma diagnosed according to strictly defined criteria is a benign urothelial neoplasm not related to urothelial carcinoma

♦

Recurrence rate is 1%, most apparently due to incomplete surgical excision

♦

Previous reported cases of inverted papillomas that coexist with carcinoma have been questioned. The majority of those reported cases probably represent urothelial carcinoma with inverted growth according to current diagnostic criteria

Macroscopic

♦

Most cases are solitary nodular or sessile lesions, smaller than 3 cm, and arise in the bladder trigone/bladder neck region

Microscopic

♦

I nverted papilloma has a smooth surface covered by normal urothelium and endophytic growth of urothelial cells arborizing extensively from the surface urothelium into the lamina propria but not into the muscularis propria (Fig. 36.31)

Fig. 36.31.

Inverted p apilloma.

♦

Most cases show anastomosing cords, columns, and trabeculae of invaginated urothelium separated by thin fibrovascular septa

Peripheral palisading of basaloid cells, thickened basement membrane, and preservation of superficial cells are characteristic of the lesion

The lesions lack exophytic growth, significant cytologic atypia, fibrovascular cores, or infiltrative growth—features commonly present in papillary urothelial carcinoma

Areas of glandular or squamous differentiation and microcyst formation may be seen in the central solid nests

Trabecular, hyperplastic, and glandular subtypes have been described

Vacuolization and foamy (xanthomatous-appearing) cytoplasmic changes have been recently reported

♦

Foci of nonkeratinizing squamous metaplasia and neuroendocrine differentiation have been reported

Focal minor cytological atypia may be present, but mitotic figures are not seen or very rare

Rare cases may have focal degenerative atypia with no clinical significance

Molecular

♦

Recent molecular studies indicate that inverted papilloma represents a clonal proliferation characterized by frequent FGFR3 mutations

Immunohistochemistry

♦

Very low tumor cell proliferation (Ki67) and rare p53 nuclear accumulation

♦

CK20 and UroVysion FISH probes are both negative

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Florid proliferation of von Brunn nests rarely represents a diagnostic concern

♦

Low-grade urothelial carcinoma has cytologic atypia, variable mitotic figures, and exophytic papillary growth

♦

Inverted variant of urothelial carcinoma has thicker and more irregular columns with loss of polarity and absence of peripheral palisading basaloid cells

Cytologic atypia and mitotic figures are common in inverted urothelial carcinom a

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree