36 1. Urology has developed as a separate surgical specialty over the last few decades and sub-specialization within the discipline is now common. Urological surgery requires open, laparoscopic and endoscopic skills and urologists have readily incorporated new technology into their daily practice, including the use of lasers, minimally invasive techniques and, more recently, robotic surgery. 2. It is common for core surgical trainees to rotate through a number of surgical specialties during their training, including urology, and it is therefore important to be familiar with the common urological operations. In addition to major life-saving surgery, urology offers a variety of day-case procedures, which provide ideal training opportunities for the surgeon-in-training. 3. Not all general hospitals have a urology department and general surgeons may be required to assess patients with acute urological problems or even operate to save life or prevent severe morbidity. It is important for surgeons to be aware of emergency urological procedures and how to recognize when urgent intervention is required in the absence of specialist colleagues. 4. Be aware of the potential benefits of specialist procedures. 1. The treatment of an acutely obstructed infected kidney is a urological emergency as patients will become very unwell with septicaemia and can die if left untreated. Obstruction may be due to a stone, congenital pelvi-ureteric junction (PUJ) obstruction or tumour within or outside of the ureter. Diabetic and immunologically compromised patients are particularly at risk. The diagnosis is made by ultrasound or CT scanning, which will show hydronephrosis and may demonstrate the underlying cause of the obstruction. The urine contains organisms that can also be cultured from the blood. 2. Decompression of the obstructed kidney using ultrasound guided percutaneous nephrostomy is the optimum treatment. Infected urine or frank pus may be drained and should be cultured. 3. Carefully secure the nephrostomy tube to the patient’s skin. When the patient has recovered from the acute illness, address the underlying cause of obstruction. Temporary drainage with a ureteric stent inserted antegrade via the nephrostomy tract will allow definitive treatment to be planned in an elective setting with the appropriate expertise. 4. Open operation is indicated only if you are sufficiently expert and it is impossible to introduce a satisfactory percutaneous drain, or if the pus in the kidney is too thick to be aspirated through the small-calibre tube used for percutaneous nephrostomy. This is not a simple procedure, so do not undertake it lightly. 5. If you undertake open operation when the cause of obstruction is a stone in the upper ureter or renal pelvis, remove it. 1. Aggressively resuscitate the patient with intravenous fluids and broad-spectrum antibiotics. If necessary, manage a severely ill patient in an intensive care unit for monitoring, and respiratory and circulatory support. 2. Review the imaging and mark the side to be operated upon. 3. Position the patient in a lateral position with the side to be operated on uppermost. 4. Have the break in the table under the 12th rib to open the flank fully. Flex the uppermost hip and knee and place a pillow between the legs. Maintain the position using a back support behind the thorax and fix the arm to an armrest with a wide adhesive bandage. 5. Check that the lowermost arm is not compressed by the patient’s body. 1. Occasionally, the pus-filled calyces ‘point’ on the surface of the kidney like ripe abscesses. Make an incision through the parenchyma at this point to release the pus. 2. More commonly, the calyces are impalpable because the overlying renal tissue is oedematous. Enter the collecting system through the renal pelvis. Follow the capsule over the convex posterior border of the kidney, keeping towards the lower pole. Find the renal sinus and gently clear away the fat by blunt dissection to reveal the posterior surface of the renal pelvis. It is not necessary to mobilize the kidney fully. 3. Make a small transverse pyelotomy (Greek: pyelos = trough, pelvis + tome = a cutting). 4. Introduce a malleable silver probe with an eyehole at the end through the pyelotomy and manoeuvre it to puncture the cortex from within a lower pole calyx. 5. Tie the tip of a size 18 F tube drain or a Foley catheter to the probe with a suture and pull it back into the renal pelvis (Fig. 36.1). Use a Willschner nephrostomy tube with a built-in malleable stylet if it is available.1 6. Close the pyelotomy using 3/0 or 4/0 absorbable sutures. Tie these sutures gently and with just enough tension to approximate the edges, as there is risk of these sutures cutting through. Anchor the catheter to the capsule using absorbable sutures. 7. Bring out the nephrostomy tube through the abdominal wall with as straight a course as possible, to facilitate changing the tube if necessary. 1. Perform gentle saline wash-outs if the percutaneous nephrostomy does not drain adequately, or insert a larger calibre tube after dilating the track. 2. If side-holes of the nephrostomy tube slip outside the parenchyma, urinary extravasation occurs. Re-adjust it under radiographic control. 3. A nephrostomy can be left in place for weeks or months, but it has a tendency to fall out however carefully it is anchored. 4. As soon as possible, refer the patient to a urologist for definitive management. 1. Common sites for stone impaction are at the pelvi-ureteric junction, the pelvic brim or at the vesico-ureteric junction. 2. The diagnosis is usually made with a non-contrast CT scan (CT-KUB) or an intravenous urogram. 3. Renal function will become acutely impaired in patients with a solitary kidney obstructed by a stone, bilateral ureteric stones, or with unilateral ureteric obstruction in patients with pre-existing renal disease. These patients need urgent intervention. 4. In the absence of sepsis or impaired renal function, the majority of patients with a ureteric calculus can be managed with an initial period of watchful waiting to allow for spontaneous stone passage. 5. Obstruction of a kidney for a short period does not usually cause serious harm. However, if there is infection or if there is poor function in the contralateral kidney, there is an urgent need to drain the kidney. 6. Unilateral obstruction lasting for over 6 hours leads to a gradual decrease in renal blood flow and after 24 hours it is reduced to 55%. Following relief of 7 days of unilateral ureteric obstruction, full recovery of renal function occurs within 2 weeks. However, obstruction of 14 days, duration results in a permanent decline in renal function to 70% of control levels. An obstructed kidney is at risk of infection and pyonephrosis (Greek: pyon = pus + nephron = kidney + –osis = production). In cases of incomplete ureteric obstruction, watchful waiting for spontaneous stone passage is usually limited to about 4–6 weeks. 7. Relieve obstruction in patients where pain is not controlled by oral analgesia. 8. In the absence of a trained urologist, an acutely obstructed kidney is best relieved using a percutaneous nephrostomy. If you do not have an expert radiologist available, perform an open nephrostomy in an emergency. 9. When the patient is not critically ill but needs decompression of an obstructed kidney, a urologist will opt to insert a retrograde ureteric stent. This is usually performed under general anaesthesia.

Upper urinary tract

INTRODUCTION

ACUTE PYONEPHROSIS (OBSTRUCTED INFECTED KIDNEY)

Appraise

OPEN NEPHROSTOMY FOR ACUTELY OBSTRUCTED KIDNEY

Prepare

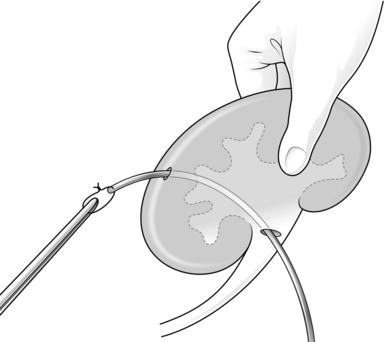

Action

Aftercare

OBSTRUCTED KIDNEY CAUSED BY A STONE

Appraise

CYSTOSCOPIC INSERTION OF A URETERIC STENT

Upper urinary tract