CHAPTER 47 Upper arm

SKIN AND SOFT TISSUE

SKIN

Cutaneous vascular supply

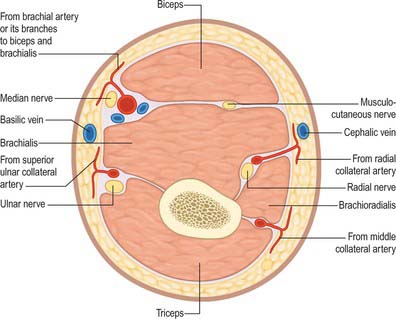

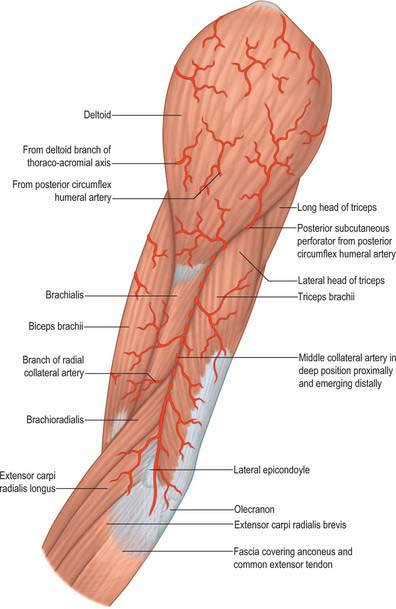

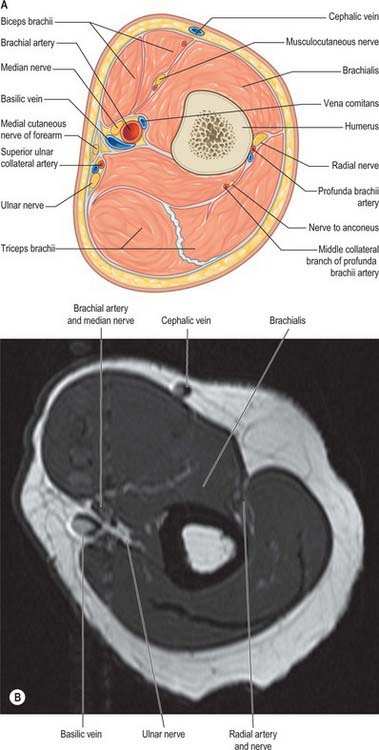

The blood supply to the skin of the upper arm can be divided into three regions with separate supply: the deltoid region, supplied by musculocutaneous perforators, and the medial and lateral regions, supplied by fasciocutaneous perforators (Cormack & Lamberty 1994; Salmon 1994) (Fig. 47.1, Fig. 47.2).

The deltoid region is supplied by the posterior circumflex humeral artery (p. 817) via musculocutaneous perforators. After the posterior circumflex humeral artery passes through the quadrangular space (p. 814) it gives off a descending branch, which runs down to the deltoid insertion and the overlying skin, and an ascending branch which passes superiorly towards the acromion, pierces the edge of deltoid and the deep fascia to fan out and supply the overlying skin.

Cutaneous innervation

The skin of the shoulder region is supplied by the supraclavicular nerves from the cervical plexus. The floor of the axilla and upper medial surface of the arm is supplied by the lateral branch of the second intercostal nerve (the intercostobrachial nerve). The lower aspect of the medial side of the upper arm is supplied by the medial cutaneous nerve of the arm. The lateral aspect of the upper arm is supplied by the upper lateral cutaneous nerve (a branch of the axillary nerve) and the lower lateral cutaneous nerve (a branch of the radial nerve). The posterior aspect is supplied by the posterior cutaneous nerve of the arm, a branch of the radial nerve (Fig. 45.15, Fig. 45.14).

SOFT TISSUE

Brachial fascia

Brachial fascia, the deep fascia of the upper arm, is continuous with the fascia covering deltoid and pectoralis major: it forms a thin, loose sheath for muscles of the upper arm, and sends septa between them. It is thin over biceps, but thicker over triceps and the humeral epicondyles, and is strengthened by fibrous aponeuroses from pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi medially and from deltoid laterally. Strong medial and lateral intermuscular septa extend from it on each side.

MUSCLES

The muscles of the upper arm are coracobrachialis, which acts only on the shoulder joint; biceps and triceps, which cross both shoulder and elbow joints; and brachialis, which acts only at the elbow joint (Fig. 47.2, Fig. 47.3).

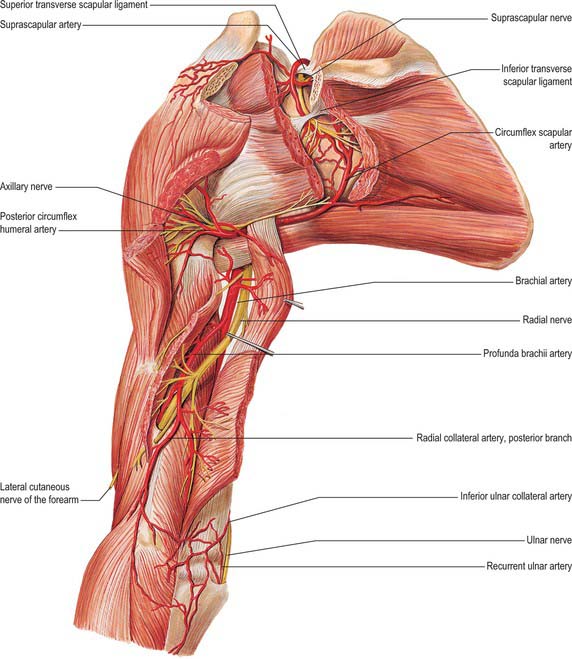

Fig. 47.3 Muscles, vessels and nerves of the left upper arm, viewed from the posterior aspect.

(From Sobotta 2006.)

ANTERIOR COMPARTMENT

Coracobrachialis

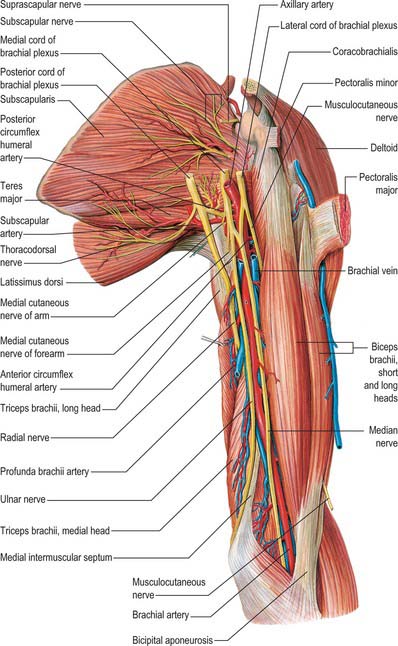

Coracobrachialis arises from the apex of the coracoid process, together with the tendon of the short head of biceps, and also by muscular fibres from the proximal 10 cm of this tendon; it ends on an impression, 3–5 cm in length, midway along the medial border of the humeral shaft between the attachments of triceps and brachialis (Fig. 46.20, Fig. 47.4). Accessory slips may be attached to the lesser tubercle, medial epicondyle or medial intermuscular septum.

One or more branches from the axillary artery pass deep to the lateral root of the median nerve, and the musculocutaneous nerve, to reach the deep surface of the muscle. Branches from the anterior circumflex humeral artery also supply the deep surface of the muscle. The accompanying artery of the musculocutaneous nerve sends a recurrent branch to the coracoid attachment and gives off a series of branches to the muscle during its intramuscular course. Accessory branches from the thoracoacromial artery provide additional supply to the superficial part of coracobrachialis.

Biceps brachii

Biceps brachii derives its name from its two proximally attached parts or ‘heads’ (Fig. 46.20). The short head arises by a thick flattened tendon from the coracoid apex, together with coracobrachialis. The long head starts within the capsule of the shoulder joint as a long narrow tendon, running from the supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula at the apex of the glenoidal cavity, where it is continuous with the glenoidal labrum (p. 805). The tendon of the long head, enclosed in a double tubular sheath (an extension of the synovial membrane of the joint capsule), arches over the humeral head, emerges from the joint behind the transverse humeral ligament, and descends in the intertubercular sulcus, where it is retained by the transverse humeral ligament and a fibrous expansion from the tendon of pectoralis major. The two tendons lead into elongated bellies that, although closely applied, can be separated to within 7 cm or so of the elbow joint. At this joint they end in a flattened tendon, which is attached to the rough posterior area of the radial tuberosity; a bursa separates the tendon from the smooth anterior area of the tuberosity. As it approaches the radius, the tendon spirals, its anterior surface becoming lateral before being applied to the tuberosity. The tendon has a broad medial expansion, the bicipital aponeurosis, which descends medially across the brachial artery to fuse with deep fascia over the origins of the flexor muscles of the forearm (Fig. 47.5). The tendon can be split without difficulty as far as the tuberosity, whence it can be confirmed that its anterior and posterior layers receive fibres from the short and long heads, respectively.

Biceps is overlapped proximally by pectoralis major and deltoid; distally it is covered only by fasciae and skin, and it forms a conspicuous elevation on the front of the arm. Its long head passes through the shoulder joint; its short head is anterior to the joint. Distally it lies anterior to brachialis, the musculocutaneous nerve and supinator. Its medial border touches coracobrachialis, and overlaps the brachial vessels and median nerve; its lateral border is related to deltoid and brachioradialis.