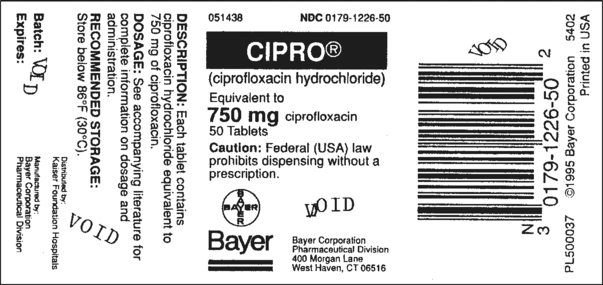

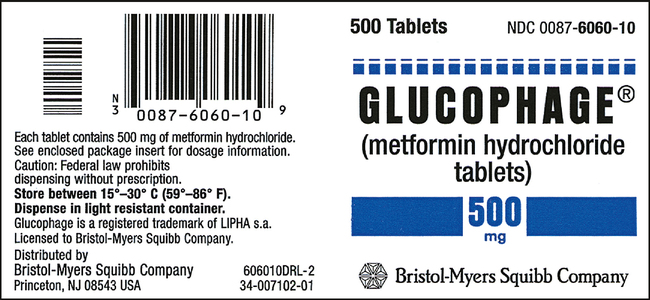

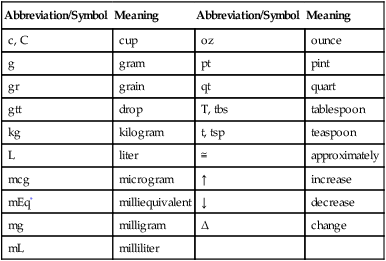

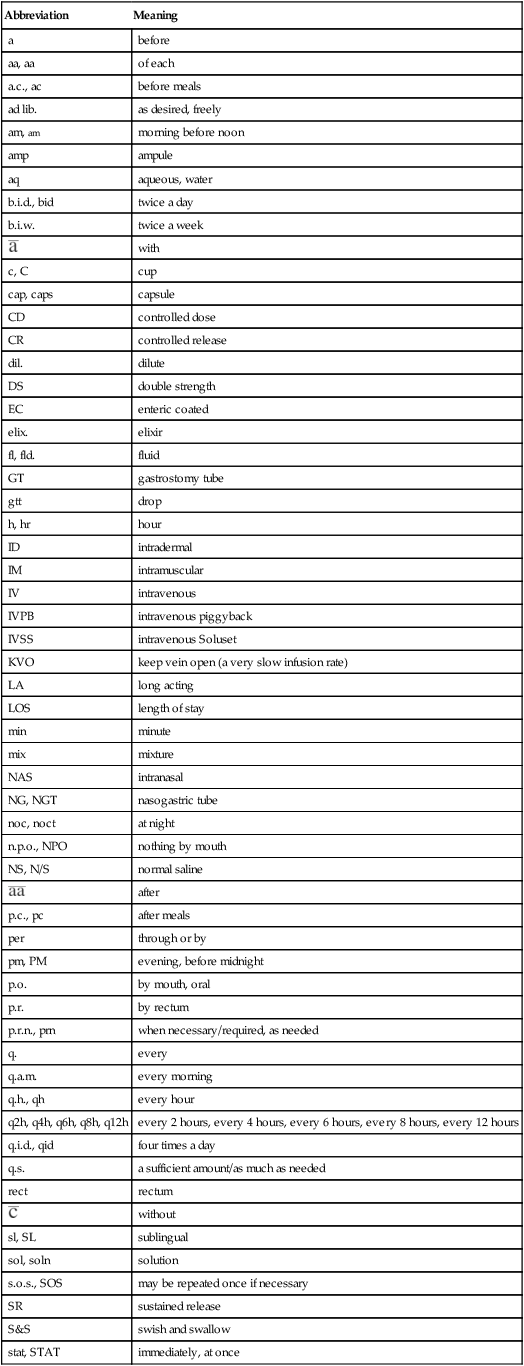

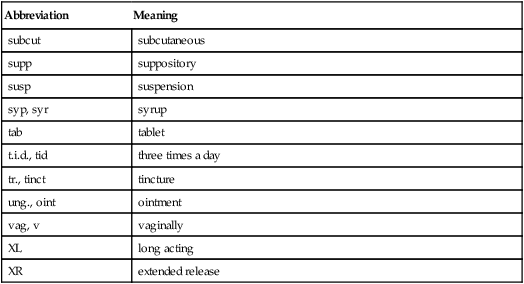

CHAPTER 11 After reviewing this chapter, you should be able to: 1. Identify the components of a medication order 2. Identify the meanings of standard abbreviations used in medication administration 3. Interpret a given medication order 4. Identify abbreviations, acronyms, and symbols recommended by the Joint Commission’s “Do Not Use” List and ISMP’s List of Error-Prone Abbreviations, Symbols, and Dose Designations Before transcribing an order or preparing a dosage, the nurse must be familiar with reading and interpreting an order. To interpret a medication order, the nurse must know the components of a medication order and the standard abbreviations and symbols used in writing a medication order as well as those abbreviations and symbols that should not be used. The nurse therefore must memorize the abbreviations and symbols commonly used in medication orders. The abbreviations include units of measure, route, and frequency for the medication ordered. The common abbreviations and symbols used in medication administration are listed in Tables 11-1 and 11-2 and must be committed to memory. The Joint Commission’s “Do Not Use” List is shown in Table 11-3, and ISMP’s List of Error-Prone Abbreviations, Symbols, and Dose Designations will be presented later in this chapter. TABLE 11-1 Symbols and Abbreviations for Units of Measure Used in Medication Administration *mEq (milliequivalent) is a drug measure in which electrolytes are measured; it expresses the ionic activity of a drug. TABLE 11-2 Commonly Used Medication Abbreviations TABLE 11-3 The Joint Commission’s Official “Do Not Use” List* *Applies to all orders and all medication-related documentation that is handwritten (including free-text computer entry) or on preprinted forms. †Exception: A “trailing zero” may be used only where required to demonstrate the level of precision of the value being reported, such as for laboratory results, imaging studies that report size of lesions, or catheter/tube sizes. It may not be used in medication orders or other medication-related documentation. © The Joint Commission, 2008. Reprinted with permission. The medication may be ordered by the generic or brand name (Figures 11-1 and 11-2). To avoid confusion with another medication, the name of the medication should be written clearly and spelled correctly.

Understanding and Interpreting Medication Orders

VERBAL ORDERS

Abbreviation/Symbol

Meaning

Abbreviation/Symbol

Meaning

c, C

cup

oz

ounce

g

gram

pt

pint

gr

grain

qt

quart

gtt

drop

T, tbs

tablespoon

kg

kilogram

t, tsp

teaspoon

L

liter

≅

approximately

mcg

microgram

↑

increase

mEq*

milliequivalent

↓

decrease

mg

milligram

Δ

change

mL

milliliter

Abbreviation

Meaning

a

before

aa, aa

of each

a.c., ac

before meals

ad lib.

as desired, freely

am, am

morning before noon

amp

ampule

aq

aqueous, water

b.i.d., bid

twice a day

b.i.w.

twice a week

with

c, C

cup

cap, caps

capsule

CD

controlled dose

CR

controlled release

dil.

dilute

DS

double strength

EC

enteric coated

elix.

elixir

fl, fld.

fluid

GT

gastrostomy tube

gtt

drop

h, hr

hour

ID

intradermal

IM

intramuscular

IV

intravenous

IVPB

intravenous piggyback

IVSS

intravenous Soluset

KVO

keep vein open (a very slow infusion rate)

LA

long acting

LOS

length of stay

min

minute

mix

mixture

NAS

intranasal

NG, NGT

nasogastric tube

noc, noct

at night

n.p.o., NPO

nothing by mouth

NS, N/S

normal saline

after

p.c., pc

after meals

per

through or by

pm, PM

evening, before midnight

p.o.

by mouth, oral

p.r.

by rectum

p.r.n., prn

when necessary/required, as needed

q.

every

q.a.m.

every morning

q.h., qh

every hour

q2h, q4h, q6h, q8h, q12h

every 2 hours, every 4 hours, every 6 hours, every 8 hours, every 12 hours

q.i.d., qid

four times a day

q.s.

a sufficient amount/as much as needed

rect

rectum

without

sl, SL

sublingual

sol, soln

solution

s.o.s., SOS

may be repeated once if necessary

SR

sustained release

S&S

swish and swallow

stat, STAT

immediately, at once

subcut

subcutaneous

supp

suppository

susp

suspension

syp, syr

syrup

tab

tablet

t.i.d., tid

three times a day

tr., tinct

tincture

ung., oint

ointment

vag, v

vaginally

XL

long acting

XR

extended release

Do Not Use

Potential Problem

Use Instead

U (unit)

Mistaken for “0” (zero), the number “4” (four), or “cc”

Write “unit”

IU (International Unit)

Mistaken for IV (intravenous)

Write “International Unit”

Q.D., QD, q.d., qd (daily)

Mistaken for each other

Write “daily”

Q.O.D., QOD, q.o.d. qod (every other day)

Period after the Q mistaken for “I” and the “O” mistaken for “I”

Write “every other day”

Trailing zero (X.0 mg)†

Decimal point is missed

Write × mg

Lack of leading zero (.X mg)

Write 0.X mg

MS

Can mean morphine sulfate or magnesium sulfate

Write “morphine sulfate”

MSO4 and MgSO4

Confused for one another

Write “magnesium sulfate”

COMPONENTS OF A MEDICATION ORDER

NAME OF THE MEDICATION

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Understanding and Interpreting Medication Orders

Critical Thinking

Critical Thinking