Fig. 4.1

Negotiating the ET catheter according to the utero-cervical angle (Used with permission from Allahbadia et al. [61])

Estimation of Cavity Depth

The cavity depth, estimated by ultrasound (US), is clinically useful to determine the depth beyond which catheter insertion should not occur. The clinical pregnancy rate (PR) is reported to be significantly influenced by the transfer distance from the fundus (difference between the cavity depth and depth of catheter insertion) after controlling for potential confounders unlike that estimated in a mock transfer 1 month before treatment. Pope et al. [12] observed that the cavity depth by US differed from cavity depth by mock by at least 10 mm in >30 % of cases and the odds of clinical pregnancy increased by 11 % for every additional millimeter that embryos are deposited away from the fundus [12].

Several authors have attested the benefit of depositing embryos at a distance of >10 mm from the fundus [13, 46, 47]. Coroleu et al. [13] reported a significantly higher (P < 0.05) implantation rate when the transfer distance from the uterine fundus at the moment of the embryo deposition in the uterus was 15 ± 1.5 mm (31.3 %) or 20 ± 1.5 mm (33.3 %) compared to when it was 10 ± 1.5 mm (20.6 %) [13]. There was no difference in the IVF or demographic characteristics among the groups. Keeping the technique of embryo loading and the number and quality of embryos transferred constant, Pacchiarotti et al. [46] also observed significantly higher clinical pregnancy rates when the distance between the tip of the catheter and the uterine fundus at transfer was 10–15 mm compared to ≤10 mm (27.7 % vs. 4 %, respectively; p < 0.05) [46].

A large recent study that included 5,055 ultrasound-guided embryo transfers in 3,930 infertile couples conducted by Tiras et al. [47] also reported higher pregnancy and ongoing PRs when embryos were replaced at a distance >10 mm from the fundal endometrial surface suggesting that a distance 10–20 mm seems to be the best site for embryo transfer to achieve higher PRs [47]. Hence, the depth of embryo transfer is an important variable in the embryo transfer technique that positively influences the implantation rates.

Demonstrating significantly reduced live birth delivery rates (LBDR) with external guidance as compared to an atraumatic ET (26.0 % vs. 32.5 %, respectively), Spitzer et al. [25] concluded that besides embryo culture and patient history, the quality of an ET might also have an important impact on pregnancy outcome. Techniques to ensure an atraumatic ET, such as mechanical uterine cavity length measurements, before starting treatment might help identify patients at risk for a difficult ET and lead to modified treatments, such as the primary use of a stylet [25].

Endometrial Evaluation

During Embryo Transfer

Ultrasound guidance offers several advantages during embryo transfer compared to the clinical touch method such as

Facilitates placement of soft catheters and increases the ease of transfer performance [7]. An atraumatic ET is crucial to the success rates of an ART procedure, and transfer difficulty and endometrial damage may compromise the outcome. US-guided ET significantly increases the ease of transfer performance compared to the clinical touch method, and clinicians recommend that embryo transfer should be performed under US guidance in combination with the use of a soft catheter to optimize embryo transfer results [6, 50]. A decrease in cervical and uterine trauma can play a role in increasing the pregnancy rates associated with US-guided transfer [6].

A significant concordance has been observed between the perceived difficulty of transfer, presence of blood on the catheter and degree of endometrial damage (P < 0.05) following hysteroscopic assessment of endocervical and endometrial damage inflicted by the embryo transfer trial. Cevrioglu et al. [24] reported significantly higher minor and moderate endocervical lesions (19 % and 3 %, respectively; P > 0.05), a higher incidence of endometrial damage (42 % minor, 29 % moderate and 29 % no damage) in the difficult ET group compared to the easy transfer group (32 % minor, 3 % moderate and 65 % no damage) and a significantly higher incidence of blood on the catheter (71 %) in the difficult transfer group compared to the easy and moderate groups (25 % and 56 %, respectively) [24]. A significantly lower (P < 0.05) implantation (13.8 % vs. 19.4 %), clinical pregnancy (31.1 % vs. 41.9 %) and live birth rate (27.4 % vs. 37.3 %) has been reported following the use of the stylet when the soft inner catheter could not negotiate the internal os during ultrasound-guided ET compared to easy ETs where the stylet was not required [23]. Despite a higher but statistically insignificant difference in pregnancy outcomes between the ultrasound and clinical touch groups, Mirkin et al. [50] observed that the frequency of negative factors typically associated with difficult transfers, such as the requirement of a tenaculum, and presence of blood or mucus on the catheter tip were significantly lower in the ultrasound-guided group in comparison with the clinical touch group [50]. Hence, US-guided ET seems essential to reduce the transfer difficulty.

A hysteroscopic assessment of the effects of embryo transfer catheters on the endometrial surface with ultrasound guidance by Ressler et al. [51] concluded that despite ultrasound guidance, endometrial disruption and catheter displacement occurs with difficult embryo transfer catheter placement, which may suggest an explanation for lower pregnancy rates in these difficult cases [51]. It would be important to emphasize the significance of using soft catheters, such as the Wallace catheters, here, along with ultrasound guidance to maximize the clinical outcome. Significantly higher pregnancy (P < 0.0005) and implantation rates (P < 0.01) [26] and significantly less frequently observed severe endometrial lesions [8] have been reported with the use of soft catheters compared to rigid catheters.

Avoids touching the fundus.

Confirms that the catheter is beyond the internal os in cases of an elongated cervical canal.

May facilitate an uncomplicated access through the cervix to the uterine cavity, thus overcoming cervical stenosis [7].

Catheter identification: Ultrasound guidance enables the easy visualization and catheter tracking of echogenic catheters, such as the Sure View® catheter (Smiths Medical, UK) [9], the echogenic WallaceTM catheter (Smiths Medical, UK) [10] and the Cook® Echo-Tip® catheter (Cook Medical, USA) [11], owing to their ultrasonic contrast properties. This, in turn, minimizes the need for catheter movement to identify the tip and results in a significantly shorter duration of embryo transfer procedure since the loaded catheter is handed to the physician and up to embryo discharge, thus simplifying USG-guided ET [9–11]. Figure 4.2 illustrates the identification of the Sure View® catheter with air bubble on ultrasound while Fig. 4.3 illustrates the cross section of the Sure View® catheter on ultrasound.

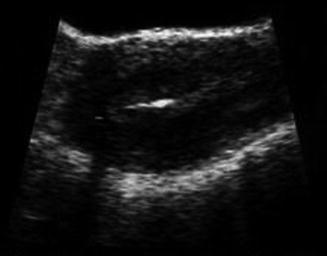

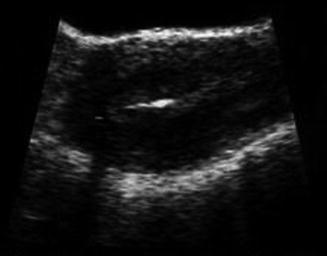

Fig. 4.2

Identification of the Sure View® catheter (Smiths Medical, UK) with air bubble

Fig. 4.3

Cross-section of the Sure View® catheter (Smiths Medical, UK) (Used with permission from Allahbadia et al. [61])

Ultrasound-guided ET may be especially beneficial in patients with previously failed IVF cycles or in patients with previous cycles when embryos were transferred by the clinical touch method [6].

With regard to the technique, both transvaginal ultrasound-guided ET (with empty bladder, using the Kitazato Long ET catheter, Japan) and TA ultrasound-guided procedure (with full bladder, using the echogenic Sure View® WallaceTM catheter, Smiths Medical, UK) yield similar clinical pregnancy and implantation rates, with no difference in the transfer difficulty and uterine cramping rates. However, the total duration of transfer (154 ± 119 versus 85 ± 76 s) was statistically significantly higher in the TV ultrasound group, but the TV ultrasound-guided procedure was associated with increased patient comfort due to the absence of bladder distension [52].

Studies have demonstrated that 3D sonography offers a higher precision in catheter placement in the endometrial cavity [53–55], noting catheter tip placement in a different and less-than-ideal area when studied with three-dimensional ultrasound in one-fifth of the patients [53]. There was a significant decrease (P < 0.05) in the clinical pregnancy and implantation rates with a disparity of 10 mm or greater in transfer distance from the fundus (TDF) between 2D and 3D images [54, 55].

After Embryo Transfer

Facilitates Tracking of the Site of Embryo Deposition [7]

The air bubble location following ET is the presumable placement spot of embryos [25]. Figure 4.4 illustrates the placement of air bubble with the Sure View® catheter. The correlation between the observation of the relative position of the air bubbles in the fundal half of the endometrial plate following US-guided ET and pregnancy rates is controversial, with some studies reporting a positive correlation [14], while recent, large studies [56, 57] failing to support a relation. Similar live birth rates were observed in patients with air bubbles moving towards the uterine fundus with ejection compared with those where air bubbles remained stable after transfer [57]. According to Confino et al. [56], bubble migration analysis supported a rather random movement of the bubbles and possibly the embryos, even with the patient in the horizontal position following ET, suggestive of active uterine contractions, that horizontal rest post ET may not be necessary, that gravity-related bubble motion was uncommon and that, a very accurate ultrasound-guided embryo placement may not be mandatory [56].

Fig. 4.4

Placement of air bubble

Experience of the Provider

According to Kably et al. [1], apart from the numerous factors that should be considered while performing an ET, the most influential factor in the outcome is the operator experience in the use of each system and not the system itself [1]. Authors have reported significant differences in clinical pregnancy rates (p < or =0.01) between different providers using the same method of loading embryos into the embryo transfer catheter and the same number of embryos (36.1 % vs. 20.6 %; P ≤ 0.01), suggesting that the physician factor may be an important variable in embryo transfer technique [15]. Desparoir et al. [16] demonstrated decreased pregnancy rates following ET when the technique was handled by less experienced providers: 29.9 % for attending physicians (>20 years of experience), 28.2 % for assistant physicians (2–5 years of experience) and 19.1 % for resident physicians (<6 months of experience) (p < 0.05). Moreover, resident physicians used the TDT catheter more often than attending physicians: 42 % vs. 21.3 % (p < 0.05) [16].

However, a few authors are of the opinion that in the hands of experienced, skilled operators, neither choice of transfer catheter, difficulty of transfer nor observations of blood on the transfer catheter caused any significant reduction in pregnancy outcomes [17]. Compared to previous ultrasonographic length measurement [58], USG-guided ET has no benefit over the clinical touch method, in terms of the clinical outcome [59, 60], in the hands of an experienced operator, its value being restricted to patients with a prior history of difficult uterine sounding or embryo transfer [59].

Conclusion

Weighing the documented evidence, and from our personal experience, we believe that ultrasound guidance is an indispensable tool in the hands of an experienced clinician for executing embryo transfer in the most accurate and atraumatic manner possible compared to the blind clinical touch method and a significant step in favour of a positive clinical outcome.

References

1.

Kably Ambe A, Campos Cañas JA, Aguirre Ramos G, Carballo Mondragón E, Carrera Lomas E, Ortiz Reyes H, Kisel Laska R. Evaluation of two transfer embryo systems performed by six physicians. [Article in Spanish]. Ginecol Obstet Mex. 2011;79(4):196–9.PubMed

2.

3.

4.

Buckett WM. A meta-analysis of ultrasound-guided versus clinical touch embryo transfer. Fertil Steril. 2003;80(4):1037–41.PubMedCrossRef

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree