U

Uremic frost

Uremic frost—a fine white powder, believed to be urate crystals, that covers the skin—is a characteristic sign of end-stage renal failure, or uremia. Urea compounds and other waste substances that can’t be excreted by the kidneys in urine are excreted through small superficial capillaries on the skin and remain as powdery deposits. The frost typically appears on the face, neck, axillae, groin, and genitalia.

Because of advances in managing renal failure, uremic frost is now relatively rare. However, it does occur in patients with chronic renal failure who—because of their advanced age, the severity of their accompanying illnesses (such as extensive neurologic deterioration), or personal preference—are unable or unwilling to undergo dialysis.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Uremic frost usually appears well after a diagnosis of chronic renal failure has been established. As a result, your examination will be limited to inspecting the skin to determine the extent of uremic frost.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ End-stage chronic renal failure. Uremic frost heralds the preterminal stage of chronic renal failure. The patient may also have pruritus, hypertension, lassitude, fatigue, irritability, and decreased level of consciousness. Additional findings include muscle cramps, gross myoclonus, peripheral neuropathies, and seizures. Anorexia, nausea and vomiting, constipation or diarrhea, and oliguria or anuria may occur along with GI bleeding, petechiae, and ecchymosis. Integumentary effects may include mouth and gum ulceration, skin pigment changes and excoriation, and brown arcs under nail margins. Acidosis results in Kussmaul’s respirations; the patient may also have ammonia breath odor (uremic fetor). Laboratory test results reveal increased blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine levels and decreased creatinine clearance.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Because a patient with end-stage renal failure is prone to seizures from uremic encephalopathy, take seizure precautions. Monitor his vital signs frequently, pad the bed’s side rails, and keep artificial airway and suction equipment at hand.

Because the patient is also prone to respiratory or cardiac arrest from metabolic acidosis or hyperkalemia, constantly monitor his respiratory and cardiac status. As necessary, administer supplemental oxygen. Intubation and mechanical ventilation may be required. Establish an I.V. catheter for medication administration. Also, begin cardiac monitoring, and be prepared to initiate cardiopulmonary resuscitation, if indicated.

Enhance patient comfort by regularly changing the patient’s position to prevent skin breakdown and by bathing him often with tepid water and minimal soap to remove the frost. Moisturize the patient’s skin with alcohol-free lotion. Trim his fingernails to prevent scratching.

Because the appearance of uremic frost invariably signals impending death, prepare the patient and his family for this eventuality, and provide emotional support. Death from uremia is generally peaceful, following a deep coma.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Uremic frost is rare in children because most undergo dialysis or kidney transplantation before renal failure reaches the end stage.

GERIATRIC POINTERS

Elderly patients with end-stage renal disease usually have other complicating medical illnesses that further reduce their life expectancy. However, maintenance dialysis can still offer such patients an improved quality of life.

Urethral discharge

Urethral discharge from the urinary meatus may be purulent, mucoid, or thin; sanguineous or clear; and scant or profuse. It usually develops suddenly, most commonly in men with a prostate infection.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Ask the patient when he first noticed the discharge, and have him describe its color, consistency, and quantity. Does he experience pain or burning on urination? Does he have difficulty initiating a urine stream? Does he experience urinary frequency? Ask the patient about other associated signs and symptoms, such as fever, chills, and perineal fullness. Explore his history for prostate problems, sexually transmitted disease, or urinary tract infection. Ask the patient if he has had recent sexual contacts or a new sexual partner.

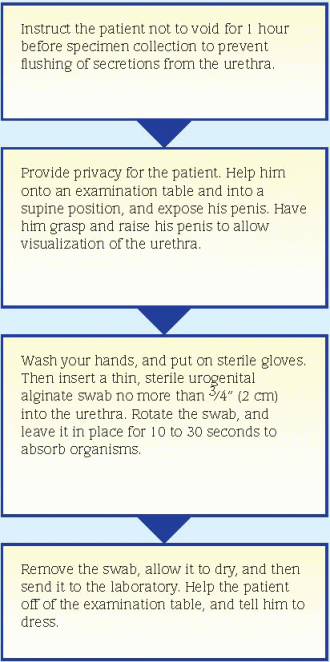

Inspect the patient’s urethral meatus for inflammation and swelling. Using proper technique, obtain a culture specimen. (See Collecting a urethral discharge specimen.) Then obtain a urine specimen for urinalysis and culture and sensitivity. Palpation of the male patient’s prostate gland may be necessary.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Prostatitis. Acute prostatitis is characterized by a purulent urethral discharge. Initial signs and symptoms include sudden fever, chills, low back pain, perineal fullness, myalgia, and arthralgia. Urination becomes increasingly frequent and urgent, and the urine may appear cloudy. Dysuria, nocturia, and some degree of urinary obstruction may also occur. The prostate may be tense, boggy, tender, and warm. Prostate massage to obtain prostatic fluid is contraindicated.

Chronic prostatitis commonly produces no symptoms, but it may produce a persistent urethral discharge that’s thin, milky or clear, and sometimes sticky. The discharge appears at the meatus after a long interval between voidings— for example, in the morning. Associated effects include a dull ache in the prostate or rectum, sexual dysfunction such as ejaculatory pain, and urinary disturbances, such as frequency, urgency, and dysuria.

♦ Reiter’s syndrome. In this self-limiting syndrome that usually affects males, a urethral discharge and other signs of acute urethritis occur 1 to 2 weeks after sexual contact. Asymmetrical arthritis, conjunctivitis of one or both eyes, and ulcerations on the oral mucosa, glans penis, palms, and soles may also occur.

♦ Urethral neoplasm. This rare cancer is sometimes heralded by a painless urethral discharge that’s initially opaque and gray and later yellowish and blood-tinged. Dysuria progresses to anuria as the urethra becomes blocked.

♦ Urethritis. This inflammatory disorder, which is often sexually transmitted (as in gonorrhea), commonly produces a scant or profuse urethral discharge that’s either thin and clear, mucoid, or thick and purulent. Other effects include urinary hesitancy, urgency, and frequency; dysuria; and itching and burning around the meatus.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Advise the patient with acute prostatitis to discontinue sexual activity until acute symptoms subside. However, encourage the patient with chronic prostatitis to regularly engage in sexual activity because ejaculation may relieve pain. To help this patient relieve symptoms, suggest that he take hot sitz baths several times daily, increase his fluid intake, void frequently, and avoid caffeine, tea, and alcohol. Monitor him for urine retention.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Carefully evaluate a child with a urethral discharge for evidence of sexual and physical abuse.

GERIATRIC POINTERS

Urethral discharge in elderly males isn’t usually related to a sexually transmitted disease.

Urinary frequency

Urinary frequency refers to an increased urge to void without an increase in the total volume of urine produced. Usually resulting from decreased bladder capacity, urinary frequency is a cardinal sign of urinary tract infection (UTI). However, it can also stem from another urologic disorder, neurologic dysfunction, or pressure on the bladder from a nearby tumor or from organ enlargement (as occurs in pregnancy).

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Ask the patient how many times a day he voids and how this compares to his previous pattern of voiding. Also ask about the onset and duration of the increased frequency and about any associated urinary signs or symptoms, such as dysuria, urgency, incontinence, hematuria, discharge, or lower abdominal pain during urination.

Also ask about neurologic symptoms, such as muscle weakness, numbness, and tingling. Explore the patient’s medical history for UTIs or other urologic problems, recent urologic procedures, and neurologic disorders. Ask a male patient about a history of prostatic enlargement. Ask a female patient of childbearing age whether she is or could be pregnant.

Obtain a clean-catch midstream urine specimen for urinalysis and culture and sensitivity tests. Then palpate the patient’s suprapubic area, abdomen, and flanks, noting any tenderness. Examine the urethral meatus for redness, discharge, or swelling. The physician may palpate the prostate gland of a male patient.

If the patient’s history or symptoms suggest a neurologic disorder, perform a neurologic examination.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Anxiety neurosis. Morbid anxiety produces urinary frequency and other types of genitourinary dysfunction, such as dysuria, impotence, and frigidity. Other findings may include headache, diaphoresis, hyperventilation, palpitations, muscle spasm, generalized motor weakness, dizziness, polyphagia, and constipation or other GI complaints.

♦ Benign prostatic hyperplasia. Prostatic enlargement causes urinary frequency along with nocturia and possibly incontinence and hematuria. Initial effects are those of prostatism: reduced caliber and force of the urine stream, urinary hesitancy and tenesmus, inability to stop the urine stream, a feeling of incomplete voiding, and occasionally urine retention. Assessment reveals bladder distention.

♦ Bladder calculus. Bladder irritation from a calculus may lead to urinary frequency and urgency, dysuria, terminal hematuria, and suprapubic pain from bladder spasms. If the calculus lodges in the bladder neck, the patient may have overflow incontinence and referred pain to the lower back or heel.

♦ Bladder cancer. Urinary frequency, urgency, dribbling, and nocturia may develop from

bladder irritation. The first sign of bladder cancer commonly is intermittent gross, painless hematuria (often with clots). Patients with invasive lesions commonly have suprapubic or pelvic pain from bladder spasms.

bladder irritation. The first sign of bladder cancer commonly is intermittent gross, painless hematuria (often with clots). Patients with invasive lesions commonly have suprapubic or pelvic pain from bladder spasms.

♦ Multiple sclerosis (MS). Urinary frequency, urgency, and incontinence are common urologic findings in patients with MS, but these effects widely vary and tend to wax and wane. Visual problems (such as diplopia and blurred vision) and sensory impairment (such as paresthesia) are usually the earliest symptoms. Other findings may include constipation, muscle weakness, paralysis, spasticity, hyperreflexia, intention tremor, ataxic gait, dysarthria, impotence, and emotional lability.

♦ Prostate cancer. In advanced prostate cancer, urinary frequency may occur along with hesitancy, dribbling, nocturia, dysuria, bladder distention, perineal pain, constipation, and a hard, irregularly shaped prostate.

♦ Prostatitis. Acute prostatitis commonly produces urinary frequency and urgency, dysuria, nocturia, and a purulent urethral discharge. Other findings include fever, chills, low back pain, myalgia, arthralgia, and perineal fullness. The prostate may be tense, boggy, tender, and warm. Prostate massage to obtain prostatic fluid is contraindicated. Signs and symptoms of chronic prostatitis are usually the same as those of the acute form, but to a lesser degree. The patient may also experience pain on ejaculation.

♦ Rectal tumor. The pressure that this tumor exerts on the bladder may cause urinary frequency. Early findings include altered bowel elimination habits, commonly starting with an urgent need to defecate on arising or obstipation alternating with diarrhea; blood or mucus in the stool; and a sense of incomplete evacuation.

♦ Reiter’s syndrome. In this self-limiting syndrome, urinary frequency and other symptoms of acute urethritis occur 1 to 2 weeks after sexual contact. Other symptoms of Reiter’s syndrome include asymmetrical arthritis of the knees, ankles, and metatarsophalangeal joints; unilateral or bilateral conjunctivitis; and small painless ulcers on the mouth, tongue, glans penis, palms, and soles.

♦ Reproductive tract tumor. A tumor in the female reproductive tract may compress the bladder, causing urinary frequency. Other findings vary but may include abdominal distention, menstrual disturbances, vaginal bleeding, weight loss, pelvic pain, and fatigue.

♦ Spinal cord lesion. Incomplete cord transection results in urinary frequency, continuous overflow, dribbling, urgency when voluntary control of sphincter function weakens, urinary hesitancy, and bladder distention. Other effects occur below the level of the lesion and include weakness, paralysis, sensory disturbances, hyperreflexia, and impotence.

♦ Urethral stricture. Bladder decompensation produces urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia. Early signs include hesitancy, tenesmus, and reduced caliber and force of the urine stream. Eventually, overflow incontinence, urinoma, and urosepsis may develop.

♦ UTI. Affecting the urethra, the bladder, or the kidneys, this common cause of urinary frequency may also produce urgency, dysuria, hematuria, cloudy urine and, in males, a urethral discharge. The patient may report a fever and bladder spasms or a feeling of warmth during urination. Women may experience suprapubic or pelvic pain. In young adult males, a UTI is usually related to sexual contact.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Diuretics. These substances, which include caffeine, reduce the body’s total volume of water and salt by increasing urine excretion. Excessive intake of coffee, tea, and other caffeinated beverages leads to urinary frequency.

♦ Treatments. Radiation therapy may cause bladder inflammation, leading to urinary frequency.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as urinalysis, culture and sensitivity tests, imaging tests, ultrasonography, cystoscopy, cystometry, postvoid residual tests, and a complete neurologic workup. If the patient’s mobility is impaired, keep a bedpan or commode near his bed. Carefully and accurately document the patient’s daily intake and output.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

UTIs are a common cause of urinary frequency in children, especially girls. Congenital anomalies that can cause UTIs include a duplicated ureter, congenital bladder diverticulum, and an ectopic ureteral orifice.

GERIATRIC POINTERS